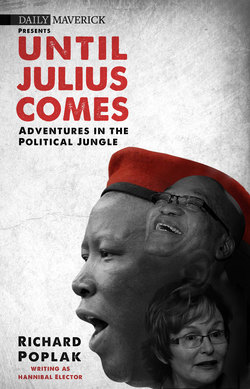

Читать книгу Until Julius Comes - Richard Poplak - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPROLOGUE

15 DECEMBER 2013, JOHANNESBURG

In which we say goodbye to a father and brace for the future

Let’s summarise.

Actually, nah. Let’s not rate speeches. Let’s not square memorials off against funerals against spirited church singalongs. Let’s not question the wisdom of Woolworths commercials. Let’s just sit with our heads in our hands for a moment. Let’s just take a deep breath and allow the newness of it all to sink in.

By ‘newness’, I of course mean the sense of living in a South Africa in which Nelson Mandela is no longer a physical presence. But I’m also referring to this new sense of ourselves that developed over the course of the week or so after he died: this sense that we’re hurtling towards our destiny as contestants in a bad reality TV show, cameras constantly shoved in our faces, in which every last one of us is the comic relief.

The designated period of mourning was meant as a squaring away, as a time of remembrance. And for those of us with an almost ancient fortitude, for those of us able to ignore the industrial-grade noise-a-thon – the tumble of tweets, the slew of selfies, the unceasing bullshit factory that is the 24-hour news cycle – for those of us able to tune it all out, perhaps those ten days actually contained meaning, rather than its inverse.

When Madiba was pronounced dead and the Official Statement was catapulted into the techno ether, I could feel it before I knew it. I don’t mean ‘feel’ in the spiritual sense of the term, although I wish I did. Rather, I heard the news choppers above me, and I could feel the information hurtling through what remains of my soul into smartphones, iPads, TVs, computers, times a hundred thousand million billion. I had one brief moment in which to say goodbye, one unfettered nanosecond in which I wasn’t part of the clutter.

And then it began.

The machine powered to life, and we descended into a pornographic netherworld defined by close-ups, by close-ups of close-ups, each image stuffed with everything except content. As the machine churned forward, Madiba grew fainter. His light dimmed, and his face – projected onto countless screens, printed in countless newspapers, used by dozens of corporations to say ‘thank you and hamba kahle’ – ceased to be his face. His beatification, which had begun long ago, was an act of multiplication – he became more anodyne, more Bible-era saintly, with each duplication.

A photocopy of a photocopied photocopy, he no longer came from a particular time or place; he drifted further and further from historical context. He was used to buff up the flagging image of presidents from countries that had once wanted him to rot in jail; his memory was used to sell overpriced nectarines and (admittedly delicious) point-of-purchase candies; he was used as the cornerstone of Brand ANC. He, who ‘taught’ us about this value and that value, became an ever-smiling minstrel figure of no known race, because racial distinctions have no place in Madiba World.

Celebrities drank from his death like vampires at a vein. Men who played him in shitty movies sat at his funeral – inspired moments of cross branding. The rich got richer as they came closer to his corpse. They grew bored during the endless ceremonies, and who could blame them? Memorials and funerals are by nature boring, unless you happen to be Irish – and Madiba, by the way, wasn’t. The famous took pictures of themselves with other famous people, and the press took pictures of the picture-taking. Facial expressions were scrutinised closely and the selfie counted as discourse, because there was nothing else of substance on the table.

I have, of course, left out the beautiful moments, the fine words spoken from the heart by friends who were actually friends, the brief seconds of dignity that Mandela was afforded in all the mess – the genuine expressions of love and pain and grief that individual South Africans poured out after they learnt of his death. Yet these same South Africans were actors in a drama they didn’t write, playing roles they were assigned by impresarios from afar. Dance, cry, complain. Exeunt stage left.

There were times during this gruesome theatre when the country seemed like an ingénue after a botched plastic-surgery procedure, nose whittled down to a needlepoint, collagen-stuffed lips where the ears should be. Nothing looked right, sounded right. Deaf people were drawn pictures by a schizophrenic who was conversing with angels – no word on whether the angels approved of all the hoopla, but I’m guessing not so much.

We were revealed, in the light of this long goodbye, as a sort of half-dystopian, subfunctional backwater with immense stadiums, fairly quick internet connections, large military airports and a deep appreciation for the burnishing sheen of celebrity. We were revealed as a place in which the presidential praise singer seemed more on top of the moment than the president did.

We were revealed as a divided country, deeply troubled, wherein our most important historical figure was over the past week co-opted out from under us. He will be replicated on posters and T-shirts and cellphone guards; he will become a character in many more movies made by men and women with only a glancing understanding of his life. Yet we somehow have to find a way back to him, a way back to his contradictions, his genius and, yes, his violence. Mourning him isn’t good enough, praising him isn’t good enough – we have to own him once again.

No nation should be afraid to grant a 95-year-old man his peace. And no nation should be governed by a T-shirt. The machine has powered down. In the real moments of silence following the mandated moments of reflection, when we’re no longer acting as cannon fodder in a reality show in which none of us are paid to perform, we might want to say a proper, dignified goodbye. And then create a possible future, rather than have others fashion an impossible past.

Thank you, Madiba. Hamba kahle. Exit stage left.

And now for Act II.