Читать книгу Kubrick's Men - Richard Rambuss - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Introduction

ОглавлениеKubrick and the Men’s Film

Stanley Kubrick’s body of work—from his early photography for Look magazine and short-form documentaries to his defining feature films—is preoccupied with men and the male condition. The persistent theme of that work, as I regard it here, is less violence or sex (as integral as those two subjects are to all the stories that Kubrick’s movies tell and thus to any account of them) than it is the pressurized exertion of masculinity in unusual or extreme circumstances, where it may be taxed or exaggerated to various effects, tragic and comic—or reconfigured, distorted, metamorphosed, and often undone. Picture, then, as one iconic Kubrick image, the ass-backward rocket ride down to earth of Major “King” Kong at the apocalyptic end of Dr. Strangelove Or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb, his uniformed thighs clamped tight around the missile shaft: an emblem that is mega-phallic and suggestively sodomitical too (Figure 1): Strangelove for sure. And picture as another, no less iconic image the terrestrial return of astronaut Dave Bowman become the perhaps postgender Star Child at the likewise fateful end of 2001: A Space Odyssey, where it is left ambiguous whether this further evolutionary iteration of man has come back to save or (like Major Kong) to destroy us. Or consider A Clockwork Orange’s devilishly charismatic Alex, psychologically rewired from a hypersexed, hyperviolent male juvenile delinquent to a mousy good boy without free will, before he’s pleasingly turned back again into what he was. Or, to move from individuals to male groups, take the assorted Marine Corps recruits in Full Metal Jacket as they are all methodically broken down and refashioned into component parts of “Mother Green and her killing machine.”

Kubrick’s movies work out case study–like narratives—many of them clinical, even mechanistic in their feel, all of them highly aestheticized in their presentation—about masculinity with the screws put to it. “Torture the women” was Hitchcock’s dictum on how to make a gripping movie. For Kubrick, the interest lay in men in extremis.

Figure 1. Loving the bomb.

Kubrick’s films have been branded masculinist, misogynist, and misanthropic. These are different sorts of charges, and I don’t see them as necessarily coextensive. But they can all be made to stick here and there. My own inclination is to think of Kubrick as one of the great auteurs of the men’s film—even though it has been said that there is really no such thing, that there is only cinema proper and the subsidiary form of the so-called woman’s picture, which includes soap opera, the weepie, and melodrama.1 Decades ago, feminist criticism set about expounding new ways of approaching (and appreciating) these genres directed toward a female audience and engrossed with, as Mary Ann Doane puts it, “problems defined as ‘female.’ ”2 One impulse animating this study of Kubrick is the concern that film criticism’s treatment of problems regarded as “male” remains, ironically, less advanced conceptually and even descriptively by comparison: this notwithstanding, or perhaps because of, the sense that the default stance of cinema is male in subject matter and address. Let me be clear, however, that the notion of the men’s film I mean to be honing here is not proffered as a dualistic counter to the women’s film, but rather as something to be viewed alongside and even at times through it.3 That is, Kubrick’s Men has turned out to be very much a book about Kubrick and melodrama—one might even say, to get ahead of what is to come, Kubrick’s male weepies. For few films of his, we shall see, go without male tears.

Kubrick’s typically revisionary, often experimental way with genre is another of this book’s principal concerns. And most of his filmmaking comes in the form of what may be thought of as male genres: the sports film (Day of the Fight); the heist film (The Killing); science fiction (2001: A Space Odyssey); the juvenile delinquent film (A Clockwork Orange, in which Alex addresses the audience directly as “my brothers”); horror (The Shining); and the war or military movie (Fear and Desire, Paths of Glory, Dr. Strangelove, Full Metal Jacket). Kubrick also mixes his male genres. Killer’s Kiss is both a sports film about a boxer and a noir gangster movie. The Vietnam War movie Full Metal Jacket is also very much a male youth film. (The malleable recruits delivered to boot camp look to be little more than teenagers.) A Clockwork Orange is both Kubrick’s first male youth film and a near-future science fiction successor/precursor to 2001.

Consider too how Kubrick’s two historical costume dramas—Spartacus and Barry Lyndon—are both titled for their male protagonists. Though one is about an ancient Roman populist hero and the other an eighteenth-century Irish gentleman-rogue on the make, both films scrutinize codes of manly conduct and play out various kinds of social, political, and sexual maneuverings among men (or among men and “boys”). Kubrick’s sex comedy Lolita retains, of course, the female title character of the famous novel that it adapts for the screen. But both the book and the movie are about obsessional, illicit male desire. Indeed, Kubrick’s Lolita frames the novel’s perverse intergenerational love story more pronouncedly in terms of erotic rivalry—and with it of course a powerful doubling connection—between men, between Humbert Humbert and Claire Quilty, whose role as a star vehicle for Peter Sellers (more on Kubrick’s actors in a moment) is much enhanced in the movie. Male desire and its discontents also churn in the undertow of the drifting plot of Eyes Wide Shut, Kubrick’s final movie, which blends aspects of the male detective film and sex film.

The point of terming Kubrick’s genres “male” isn’t at all to stipulate their audiences or sphere of appeal. Nor, of course, is the men’s film strictly the domain of male directors, as the career of Kathryn Bigelow compellingly illustrates.4 My grouping of Kubrick’s movies under the heading of men’s pictures is to put forth a simpler claim about them. It is that his work amounts to a continuing reflection, through image and story, on maleness, not only in the present but also in history and the future. The stories that Kubrick’s movies tell range from global nuclear politics to the unpredictable sexual dynamics of what appears to be a picture-perfect bourgeois marriage; from a day in the life of a New York City prizefighter preparing for a nighttime bout to the phases of human evolution. All of these stories center on men. Indeed, in a number of Kubrick’s films—including several widely regarded as among his greatest: Paths of Glory, Dr. Strangelove, and 2001—the world depicted is all but all male. Kubrick’s movies are concerned with male sociality and asociality, especially apart from or notwithstanding the presence of women. They present male doubles, duos, pairs, rivals, and other forms of replication. They treat the romance of men and their machines, and men as machines. They elaborate intensely conflicted forms of male sexual desire. They spectacularize male violence and combat. They render male exertion and also exhaustion.5 And they are also—though this dimension of Kubrick’s work has thus far been less explored—very much about male manners, style, and taste.

I find that I keep returning in my work to Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick’s observation that “some people are just plain more gender-y than others.’ ”6 This book extends that notion to Kubrick’s oeuvre: that it is especially “gender-y,” and this in registers whose complexity and variability repay more sustained critical attention. Kubrick is a male director who made movies about men adapted from male-authored texts. This may sound like the makings of an ineluctably masculinist project. But what it means to be or to act or to feel like a man in Kubrick’s movies is far too fractured, too dissonant, and ultimately too strange to be reduced to that.

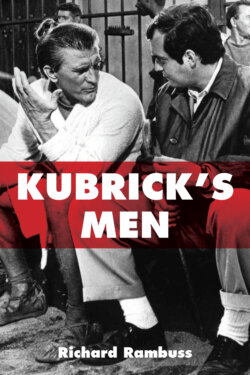

There is another sense in which Kubrick is a men’s picture filmmaker: a fairly obvious one, but worth pointing out here, I think, given that the title of this book is Kubrick’s Men. It’s that all the stars in Kubrick’s movies are male stars. Kirk Douglas, Sterling Hayden, Laurence Olivier, Charles Laughton, Peter Ustinov, James Mason, Peter Sellers, George C. Scott, Ryan O’Neal, Jack Nicholson, Tom Cruise: that’s the Kubrick firmament. There are no female stars in leading roles in any of Kubrick’s films until the final one, Eyes Wide Shut, which costars Cruise’s wife at the time, Nicole Kidman, and even then she hardly shares equal screen time with him. Otherwise, the parts for Kubrick’s women are mostly roles for character actors the likes of Marie Windsor, Shelley Winters, and Shelley Duvall. They are all extraordinary in their way, and in the case of Winters scene-stealing, but the characters they play remain on the outside looking in on predominantly male narratives.

Although this study is not organized chronologically, the first chapter is devoted to Kubrick’s earliest work. It opens with his photojournalism for Look magazine, where he landed a job right out of high school in 1945. At Look, Kubrick learned to tell stories through images. As a staff photographer—reportedly the youngest in the magazine’s history—he had all kinds of assignments and took thousands of pictures, hundreds of which were published. I like to think that photographing male entertainers (Montgomery Clift, Leonard Bernstein, Frank Sinatra, Guy Lombardo, New Orleans Dixieland jazz musicians, etc.) and male athletes (especially boxers and wrestlers) were among Kubrick’s fortes. Weegee (Arthur Fellig) and Diane Arbus are the names most likely to come up as reference points of comparison and inspiration for Kubrick, the young photographer. My consideration of his photography juxtapositionally brings in two later male portraitists, Robert Mapplethorpe and Bruce Weber (also, like Kubrick, a documentary filmmaker), as an angle onto other, less considered gendered aspects of Kubrick’s early work.

This chapter next turns to the three surviving documentaries Kubrick made after he left Look in 1950 to devote himself to movies. They are quite different in their subject matter and genre: one is a sports short, another is a newsreel human interest story, and the third is a promotional film. I see these precociously stylish short-form film “exercises” as of a piece, however, for several reasons, especially because of their focus on male subjects. The most interesting of the lot is the first one, Day of the Fight, about a handsome Greenwich Village boxer named Walter Cartier. I surmise that for Kubrick a good deal of this subject’s appeal—both visually and thematically—has to do with how Cartier comes with a twin brother, who (at least as Kubrick’s documentary stages it) lives with him and manages his career in the ring. The Kubrick motif of the double or multiple takes root here, in the very first film that he made, and it gives this remarkable sports short an uncanny aura. Before he made a movie about Walter Cartier, Kubrick first shot him for a Look photo-essay titled “Prizefighter,” which I also take up here at some length. Kubrick replicates images from both “Prizefighter” and Day of the Fight in Killer’s Kiss, his second feature film, likewise about a New York City boxer. This chapter treats Killer’s Kiss as an early illustration of the formal, thematic, and we might even say theoretical affiliations between Kubrick’s three bodies of work: his photographs, his documentaries, and his feature films. The kinds of contact points found here also point to a notable aspect of Kubrick worth remarking from the outset: namely, the autoreferentiality of his art, which is markedly imitative of itself and quickly became its own main influence. That formal and thematic quality will make Kubrick’s cinema very much a world unto itself.

Boxing is highly theatrical fighting—the ring, the audience, the Marquess of Queensberry rules—that is for real. It’s the combat sport that comes closest in its aim, which is overcoming the opponent by way of injuring him, to war. And war is one of Kubrick’s principal subjects. The war film is the most prevalent genre in his filmography, while battle scenes and military concerns also figure significantly in other kinds of Kubrick movies. Chapter 2 focuses on Kubrick’s first three war films: his little-seen debut feature, Fear and Desire; his World War I military melodrama, Paths of Glory, often heralded as one of the greatest antiwar films ever made; and Dr. Strangelove, his nightmare spoof about the war that ends all wars, along with everything else. I set up my treatment of Kubrick’s war films with a glance at his unmade epic biopic about Napoleon, among the most storied of all military subjects. The chapter concludes with another Kubrick epic, 2001: A Space Odyssey, contextualized here as a Cold War film. It locates mankind’s disposition toward violence and war—by that time augmented with world-obliterating powers—in the process by which man became man.

Arousal is my way here into Kubrick’s war films. Not just cinematic violence as itself a turn-on, though its stimulating properties are engaged as early on as Fear and Desire (reflected in the movie’s libidinal title), and then given the most earth-shaking climax imaginable (or unimaginable) in Dr. Strangelove, which I see as a kind of terminal war film. (What do you do in that genre after this?) So there is the excitement of violence in Kubrick, of course. But I am also taken with how Kubrick’s war films draw upon, how they activate the stimulations of art, including but not only their own filmmaking art. Here talk of weapons, troops, tactics, and casualties is juxtaposed with, and at times informed by, questions of beauty, style, and taste. All the show-and-tell of literature, architecture, furniture, and fine art that comes with the bravura combat sequences and rationalized military maneuverings is the stimulus for my attempt to work out aesthetical readings of Kubrick’s war films. The point of such an approach is far from suggesting that his movies dignify, much less glorify, war. (Or art, for that matter, a point further considered in relation to A Clockwork Orange in Chapter 4.) But it does seem to me that none of Kubrick’s war films really answer to any kind of antiwar war film imperative, if that’s even what one here comes looking for.

Another way to say this is that in Kubrick politics tends to be subordinate to stylistics. For Kubrick’s cinematic storybook about men in extremis also reads as an anthology of male types, roles, and gender styles, which are relentlessly counterposed in precarious, highly combustible relationship to each other. There may be no more consequential example in all of cinema of the clash of male types than Dr. Strangelove, where the film’s over-the-top male satire also provides an alibi for what is concurrently a doting, technically detailed romance of men, machines, and the military.7

Chapters 3 and 4 on Kubrick and male sexuality take the matter of male difference in another direction. They offer the first detailed treatment of the homosexual content (mostly but not exclusively male) in Kubrick’s work. Though he never made a gay-themed movie per se, hardly any Kubrick film goes untouched by something homosexual somewhere. Chapter 3 pursues that claim in Lolita, The Killing, and Spartacus, films that Kubrick put out while the Motion Picture Production Code was in effect. It banned, among so many things, any explicit acknowledgment of “sexual perversion,” homosexuality naturally included. Chapter 4 turns to Barry Lyndon, A Clockwork Orange, and Eyes Wide Shut, three films that Kubrick made after the Production Code was replaced in 1968 by the Motion Picture Association of America film rating system. This chapter concludes with a short section on The Shining, from which the briefest of scenes provides, as I explain below, the inspiration for the line of inquiry followed here.

Chapters 3 and 4, paired, track where and how the homosexual shows up in a Kubrick film. We will find that homosexuality tends to be a marginal element, set at the sidelines of the movie’s main story—though there, at the margins, the half-life accorded it can momentarily be quite spectacular. My term for this homosexual trace found throughout Kubrick’s movies is apparitional, borrowed from an important book by Terry Castle on lesbianism and here given a local habitation (if not a name) in the two gay-acting ghosts ever so briefly glimpsed in The Shining once all hell has broken loose.8 One might be tempted to say that homosexuality is the specter that haunts Kubrick’s men’s films—and, having said that, not only his various iterations of the men’s film but just about all men’s films. Yet with respect to Kubrick, I don’t so much mean haunt in the sense of casting a shadow over, much less of looming fear or dread. Rather, I see the gay specter in Kubrick’s movies more as a revenant, as something that keeps coming back—as recurring, though transient, visitations. (Perhaps this is why the prospect of a homosexual encounter comes up in both Lolita and Eyes Wide Shut, along with The Shining, in a hotel setting.) Sometimes the specter of homosexuality is just there in Kubrick. In other of his films, it emits some force, whether operative at the level of individual characters or (of more interest to me) narrative structure.

I originally conceived of this topic as material for a single chapter. The decision along the way instead to apportion Kubrick’s treatment of male sexuality and homosexuality into two, historically organized chapters would, I presumed, set in sharper relief the differences between the Production Code–era films and those made when it was no longer in force. And some notable differences do in fact thus show up. But they are chiefly along the lines of the expected “progression” from insinuation in the earlier films (say, Crassus’s encoded taste for “both snails and oysters” in Spartacus) to the various kinds of more explicit gay expression found in the later ones. The word “homosexual,” for instance, is uttered for the first and, as it happens, only time in a Kubrick movie in A Clockwork Orange, which is also the first movie that Kubrick did after the Production Code’s demise, part of that film’s “showing off” its lack of restrictions. This X-rated art film is, as we shall further see, also flamboyantly decorated with spectral gay porn. But mostly the homosexual element appears rather the same across all these films: it is incidental to Kubrick’s men’s films, an accompanying feature, part of their (male) world-making. This, as I see it, is the paradox of homosexuality in Kubrick: same-sex interest and display are intriguing enough to these films always to make some kind of appearance, but not important enough to mean all that much of anything when they do. It may be just there, but it is there.

Another thing that the Kubrick films discussed in Chapters 3 and 4 have in common is that they are all adaptations from literary sources, novels in fact. The translation from page to screen is an issue of considerable interest in Kubrick, given that every one of his feature films, apart from the first two—Fear and Desire and Killer’s Kiss, which he would subsequently all but disown—are adaptations. (Kubrick’s literariness, no doubt, is part of my attraction, coming to these films by way of training in literary studies.) A remarkable feature of the movie adaptations pored over here is that the kind of minor, though fascinating, homoerotic and homosexual content referred to earlier has been added to them. That is, in most cases it isn’t there in the source text—and what to make of that? These two central chapters twist their rereadings of an assortment of early to late Kubrick films around that added homosexual content, however peripheral, however superfluous. I suppose that what is on offer here could be described as a gay reading of male sexuality, and not just male homosexuality. The hope is that this aslant approach will provide some new perspectives regarding gender and sexuality in Kubrick’s work, but also with them some different vantages onto narrative, style, and affect (which brings us back to Kubrick, the male melodramatist).

Kubrick’s men are predominantly, but not exclusively, white. Male racial difference, noted throughout this study, comes more to the fore in the discussion of Spartacus in Chapter 3, in particular the character of the Ethiopian gladiator Draba, played by the towering former star athlete Woody Strode. And it comes again to the fore in the next chapter’s consideration of The Shining, where Scatman Crothers’s Dick Hallorann is a rival, second father to Danny through his and the boy’s shared supernatural ability “to shine,” to communicate telepathically. Kubrick studies (the work at hand included) has yet to deliver the extended study of race in Kubrick’s movies that important topic warrants; but any account of Kubrick’s men would be deficient without spotlighting Strode’s Draba and Crothers’s Hallorann. Their roles may be mostly shaped by the liberal trope of the “good man Black man.” Indeed, Spartacus will hold up Draba (though in his death) as a new model for masculinity and the inspiration for the slave rebellion Spartacus himself (of course) will lead.9 But the outsized impression made by Strode’s and Crothers’s performances exceeds their supporting roles as well as the stereotypes they seem meant to embody. (This is not unlike my argument about homosexuality’s functioning here.)

Chapter 5 returns to Kubrick and the war film, a genre that he kept experimenting with throughout his career. One of the things the war or military movie is always about, on some level, is the relationship between men and their masculinity. War films put masculinity in question, throw it into crisis. What does it mean to act like a man, especially in extreme circumstances, war being the most extreme? This final chapter is given over to Full Metal Jacket, Kubrick’s last war film, which I view as his most revisionary take on the genre and with it on gender. Earlier I proposed that Kubrick quickly became his own chief influence. This chapter also returns to the question of influence, now including Full Metal Jacket’s influence on works likewise concerned with the gendered dynamics of the military by other filmmakers and also writers.

Kubrick explained in a 1987 interview coincident with the release of Full Metal Jacket that he wanted “to explode the narrative structure of movies.”10 His bifurcated, two-act and pointedly “meta” Vietnam War movie does unusual things with structure, setting, and character. Instead of pursuing a main storyline (or a few interwoven narrative strands), Full Metal Jacket unfolds as a succession of nearly freestanding vignettes—a series of “dispatches” from the war (to invoke the acclaimed Vietnam War memoir of Michael Herr, a coauthor, with Kubrick and Gustav Hasford, of the screenplay). Similarly, this film, which Kubrick interestingly cast without a major star, has a fairly radical, one might say dissolved notion of what counts as a leading man in a military film, particularly—and this is germane to my consideration of Full Metal Jacket—a Marine Corps film. Also related to this, I think, is the way that Full Metal Jacket stands apart for its abnegation of the male melodrama that powers so many of Kubrick’s films, as well as the war film genre more generally.

The aim Kubrick expressed of wanting violently to undo narrative structure can be extended to what happens in this film to our frameworks of gender. Whereas the plot and subplots of Kubrick’s World War I movie Paths of Glory turn on the question of what is required of a man once he becomes a soldier, Full Metal Jacket starts off preoccupied with an antecedent question: How do you refunction the boy next door—just about any boy—into a hard-hearted, semiautomatic killer, into a cog in “Mother Green and her killing machine,” as this martial male family here refers to itself? On this account, the first third of Kubrick’s Vietnam War film is spent on Parris Island at boot camp. There the Corps’ micromanaged control technologies of discipline, drill, and regimentation are compellingly rendered—and also aestheticized—according to Kubrick’s own masterful visual style. These transformative physical processes are matched with a methodical assault on the individual male self, and this most intensely so (at least in Kubrick’s movie) around the especially vulnerable pressure points of gender and sexuality.

Hypermasculinity, including racialized hypermasculinity, would be one way to name the theoretical concern that animates this concluding chapter, with an understanding that here amplification turns strikingly transmutative, distortive. Nearly all of this book’s overarching concerns—the all-male group or institution; male conflict and male-on-male violence; homoerotic/homophobic male homosociality; male sadomasochism; the male body in extremis; and especially male vulnerability—show up with a vengeance in Kubrick’s late-’80s hyperviolent, hypersexualized Vietnam War film. Then factor in the highly ritualized, fetish-rich ethos of the Marine Corps: as represented here, its own totalizing male world. What does gender look like, how does it operate in this setting? Whatever it means to be or to act male here, it’s not something, apparently, that the recruits naturally instantiate when they arrive at boot camp. “Sound off like you’ve got a pair,” the film’s Sergeant Hartman demands in his first scene with them in the barracks, insinuating that here they are taken, at best, as only notionally male.

Such mockery, along with the drill sergeant’s interpellation of those in his charge as “ladies,” “pussies,” or “dick suckers,” may strike veteran viewers of the military training movie as “merely” conventional. But the sexual effects mobilized in boot camp seem to me less assimilable to normative versions of maleness (however imagined) than is the case with the usual men-in-groups ritual fare of temporary, playfully derisory sexual reversal or inversion. Of course, the very conventionality of all this is itself of interpretive interest. To recognize that these are the commonplaces of male hazing, which is to say male fashioning, shouldn’t entail that we then abstain from thinking about them as meaningful. As conventions, these terms and gestures may rather be seen as thick with significance.

Again, what does gender look like in such a setting? And what about sex and sexuality? Throughout this book I have tried to be sparing in my use of the word “queer,” sometimes now a lazy shorthand in gender and sexuality studies.11 Yet it is hard not to reach for that term when it comes to Full Metal Jacket. The question of sexuality in terms of this movie hardly answers to the models that bear on the readings of Kubrick’s films offered in Chapters 3 and 4. Structurally speaking, male sexuality in Full Metal Jacket is not hetero or homo, and, while it melds aspects of both, bisexual doesn’t really describe it either. The eroticism rhetorically activated around the film’s marines, which plays no small part in making them marines, seems instead to point toward their own extreme alternative sexuality.

Ending Kubrick’s Men with Full Metal Jacket, which isn’t Kubrick’s last film, only his last war film, may seem eccentric, perhaps even a touch perverse. So too (or maybe all the more) my giving this one film, not typically judged to be among the director’s signal works, its own chapter. I do so chiefly because, as I have here begun to suggest, the articulations of masculinity in Kubrick’s final war film seem to me both the most intense and estranging in his work. This privileging (if that’s the word for it) of Full Metal Jacket may be indicative of the book as a whole, which proved to be idiosyncratic in several respects. Personal too. Full Metal Jacket is the first Kubrick film that I wrote about and taught. It is also the first Kubrick film that I saw in the theater upon its release. It seems fitting to return at the end of this reading of Kubrick’s body of work to the place where this began for me.

Although this book considers all thirteen of Kubrick’s feature films, plus his three documentaries, they are not accorded equal attention, and this for no one reason. As it happens, fewer pages are devoted here, for instance, to two of Kubrick’s most widely discussed films, 2001: A Space Odyssey and The Shining. And I found that I had as much or more to say about early Kubrick, lesser or even “bad” Kubrick (it’s left to the reader to determine what film or films would go in that category), and also the Kubrick film often treated as not one (namely, Spartacus), as I do about what have come to be regarded as Kubrick’s major works. In terms of generic classification, I wound up being especially drawn to his war films and his sex films, though of course those two groupings could be seen to embrace every film this director made.

I wouldn’t say that this study of Kubrick quite qualifies as an expression of the “too-close viewership” named and dazzlingly exemplified in D. A. Miller’s recent book Secret Hitchcock.12 But my attention here, like Miller’s, tends to fix on brief scenes, background matter, and minor details, including the occasional continuity error, along with allusions, puns, evocations, and other kinds of ghostly visual and textual traces. This is partly because my own tendency as a reader and viewer is to get caught up in the small—and, to use again a Kubrickian term, strange—particulars. It’s also because I have found that such little things point to different interpretive paths into an already much written about filmmaker. As for the big picture, I recognize that I am hardly the only critic to remark the manifestly male orientation of Kubrick’s work.13 The same goes for its heightened aestheticism. In this book, I want to make even more of both matters, and at times to try to think about them in relation to each other.