Читать книгу Kubrick's Men - Richard Rambuss - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

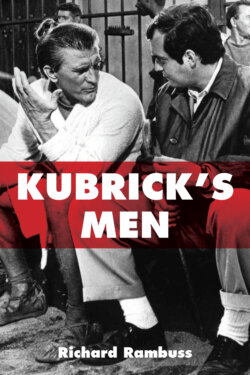

Fight Films

ОглавлениеWalter Cartier plays himself in Kubrick’s debut film, Day of the Fight. Its title echoes a headline in “Prizefighter” that’s also reused in the Rocky Graziano photo-story. The sixteen-minute documentary opened at the Paramount Theater in New York on April 26, 1951—the bottom part of a double bill—and was widely distributed by RKO-Pathé for its This Is America series. Kubrick, then twenty-two, directed and shot the film himself, with the help of Alexander Singer, a high school friend, as the second cameraman. Gerald Fried, another acquaintance from Kubrick’s schooldays, scored the film, providing a brass-heavy martial fanfare main theme, which later came to be called “March of the Gloved Gladiators.”9

Richard Combs describes Day of the Fight as “Startlingly … not so much a rough draft as a perfect miniature of the feature films that were to follow.”10 Singer, who became a director himself, recounts how Kubrick “did that sports short as if he were doing War and Peace.” “He was meticulous with everything, from scripting to editing. Stanley was a full-blown film-maker instantly.”11 Walter Cartier, not only the subject of Day of the Fight but also a technical consultant on the film, makes a similar point in his own terms: “Stanley comes in prepared like a fighter for a big fight, he knows exactly what he’s doing, where he’s going and what he wants to accomplish. He knew the challenges and he overcame them.”12 Michael Herr, a coauthor with Kubrick of the screenplay for Full Metal Jacket, provides a variation on this theme in coming to the defense, many years after its release, of Kubrick’s other boxing movie, the not so well-regarded Killer’s Kiss. Herr reminds us that Kubrick made that early film “under severe time and money limitations, which he addressed like a soldier.” “And,” emphasizes Herr, “not a boy soldier either.”13 Such talk becomes a trope, a kind of Kubrick “thing”—a male thing. We find versions of it in firsthand reminiscences of Kubrick’s way on the set, as well as in theoretical contemplations of his mode of auteurism. Kubrick, the director as a prizefighter. Or soldier. Or general. Then there’s Kubrick and his films as a brain (that’s Deleuze)—or a computer. HAL, c’est moi?14

Figure 10. Rocky Graziano in the raw. (Stanley Kubrick for Look magazine. Museum of the City of New York. Used with permission of Museum of the City of New York and Stanley Kubrick Film Archives.)

The Look photo-essay “Prizefighter,” the documentary Day of the Fight, and the feature film Killer’s Kiss make a mixed photography and film triptych on boxing. In segueing from Kubrick’s photographs to his films, I want to dwell a while on Day of the Fight before turning to Killer’s Kiss. I do so not only because this now fairly obscure, short-form documentary made for such an accomplished debut, a debut already compact with what will endure as Kubrick’s preoccupations, but also because (though this may be to say again what I just said) the first film that Kubrick made is all about male display, male contest, and male relations.

In turning his Look picture-essay on Cartier into his debut motion picture, Kubrick repositions the boxer in an even more ritually intensive same-sex world. A male voiceover narrator—a favored expository device of Kubrick’s from the beginning—takes us through it. Kubrick considered Montgomery Clift for the part, but ultimately he decided on veteran CBS news reporter and later anchor Douglas Edwards. Cartier, Edwards has us know, shares his small Greenwich Village apartment with his aunt, but she is nowhere to be seen in the film. Nor is the girlfriend who appears with him in two shots in the original photo-piece. The narrator further informs us that Cartier’s father is away and that his mother died when he was a little boy. In the absence of these others, the documentary narrows its focus to Cartier and his brother—his twin brother, Vincent. Vincent is a lawyer in New Jersey and also Walter’s manager. Singer, who operated the second camera on the film, reminisces, “Walter Cartier was good-looking and able. He surely looked good—and his brother, Vincent, looked good—and the two of them together were really quite marvelous figures.”15 The nom de guerre under which Walter first fought was “Wally ‘Twin’ Carter.” Walter Cartier is the first of Kubrick’s men; but he is also one in a line of male duplicates—twins, doubles, doppelgängers—to be turned out in Kubrick’s movies. (Even HAL has a twin back on earth.)

The edgy hourly countdown to the late night bout begins at 6:00 a.m., with Walter and Vincent waking up together in a double bed. “Walter is on the right,” the narrator must point out of the two “boys,” as he calls them, who are dead ringers for each other. (And it’s twin brother Vincent in that bedroom photograph in the Look magazine “Prizefighter” photo-essay.) We hear how Walter and Vincent started exhibition boxing each other when they were just little boys. Apparently inseparable, the twins continued to do so during the war in the Navy, “where they were in the same outfit together.” While the voiceover relays this, the film supplies a neat visual pun. Out of bed and now dressed, the brothers, still all but indistinguishable, are once again in the same outfit. This time it’s coat and tie (Figure 11). That’s Walter now on the left, “wearing the bowtie,” the narrator indicates, as the boys sprint shoulder to shoulder across a busy downtown street.

What am I insinuating? Simply that even as Kubrick’s fight movie shapes up, as others too have observed, as a formalist study of doubles—and this is Joyce Carol Oates’s take On Boxing tout court16—it also comes to read as a kind of period portrait of a male “couple.” The visual and thematic “homo”-ness of the encounter in the ring, including its homoeroticism, in this case bends back home as well. Kubrick’s sports documentary is notable, we have already glimpsed, for the domestic vignettes that it stages. In addition to the uncanny image of the adult male twins side by side in a double bed in their pajamas, we watch Vincent serve Walter “a fighter’s breakfast” in the apartment’s cozy kitchen. This is where their aunt shows up in the corresponding picture in the “Prizefighter” photo-essay, but not here in the movie. “Now they live,” pronounces the narrator, “as they used to years ago, the two boys—and Walter’s dog.” Fight day thus ironically occasions the irenic restoration of a fantasy of parentless fraternal exclusivity: brothers together, no others.

Figure 11. The Cartier twins, Walter and Vincent, in Greenwich Village.

And dog makes three. The Cartier boys didn’t have a pet; this was Kubrick’s addition to the domestic storyline that he wanted to foster for them. Recall the decorative role that dogs play in Bruce Weber’s work, which culminates in the 2004 documentary A Letter to True about his own beloved pack of handsome golden retrievers. Dogs are what Weber’s sportive boys have—that and each other, if not girls. A later scene in the film of the Cartiers killing time alone at home before the fight shows Walter cuddling his spaniel, while Vincent, puffing on his pipe, approvingly looks on. Just as the twins double one another, Vincent plays a second, doubly gendered double role—a brother who is both mother and father—in this day-of-the-fight male household.

While Walter’s pet plaything kisses his face and he affectionately blows in the dog’s ears, we hear how tonight he will “go to work [in the ring] with these same kind, playful hands.” Fast forward to Walter in the locker room just before the fight:

Walter isn’t concerned with the hands of the clock now, just his own hands. As he gets ready to walk out there in the arena, in front of the people, Walter is slowly becoming another man.… The hard movements of his arms and fists are different from what they were an hour ago. They belong to a new person. They’re part of the Arena Man: the fighting machine that the crowd outside has paid to see in fifteen minutes.

The mind/body processes of becoming machinic are another abiding interest of Kubrick’s work, stretching from this sports short through all his war films. Walter Cartier wielded a knockout punch both in his right hand and his left hand, twin engines of unconsciousness. The boxing claim to fame of this “fighting machine” was knocking out an opponent in the first round in less than one minute with one punch.

There is another personal dimension to this boxer—and something else the brothers share—that the film is interested in. The soulful middleweight Walter and his twin are both devout. A holy picture and crucifix hang above their bed. Later in the film, just before he is called from the dressing room to the ring, Walter gives Vincent the saint’s medal that he wears around his neck for safekeeping. And the scene on the street where the two boys are all but identically dressed up has them on their way, not from any of the Greenwich Village bars seen in a row in the background, but rather to church. There they kneel alone and side-by-side (again looking so good together) at the altar rail. “It’s important for Walter to receive Holy Communion,” intones the narrator ominously, “in case something should go wrong tonight.” A low, tilt angle shot of a Pietà—Jesus, his loincloth comparable to what little a boxer wears, laid out stone cold dead over Mary’s lap—feels foreboding.

After receiving the host from a priest and breakfast from his brother in paired, consecutive scenes of feeding—soul, then body—Walter undergoes another kind of day-of-the-fight rite: the mandatory prefight weigh-in and physical by a doctor. This scene, also pictured in both of Kubrick’s boxing photo-stories for Look, returns us to the question of bodily display. As I remarked earlier, there may be more female than male flesh on view in Kubrick’s movies, especially when it comes to nudity in an explicitly sexual context. But there is another kind of male exhibitionism that recurs in his art, both the photography and the films. These are scenes of looking at the male body as it is put on display for examination and handling, whether in athletic, military, or medical contexts: scenes imbued with their own, principally disciplinary, erotics. The most revealing comes in A Clockwork Orange when Alex is being processed for incarceration. “Get undressed … and bend over,” he is ordered by the Chief Guard, in a scene that Kubrick’s film adds to Anthony Burgess’s novel. Consider too in this context the scene in Full Metal Jacket where facing rows of marine recruits stand at attention on their footlockers in their white boxers and T-shirts. Their drill inspector moves slowly down the line to inspect the recruits’ outstretched hands, nails, and feet. In Spartacus, it’s teeth: “As the teeth go, so go the bones.” Thus declares the slave trader Batiatus as he peers into the mouth of a brawny slave he considers purchasing for his gladiator school. Then he learns that Spartacus has used his teeth to hamstring a slave guard. “How marvelous!” he says, and buys him on the spot. Spartacus is another one of Kubrick’s fight films; it features both the ring and the battlefield. During one of its own “boot camp” scenes, different colored paints are swiped across Spartacus’s bared body to target the most vulnerable areas. “You get an instant kill,” says the trainer, “on the red”—the gladiator’s version of the boxer’s knockout punch, which also on occasion proved fatal. “For the blue you get a cripple.” For the yellow “the slow kill.”

In Day of the Fight, the combatant’s body is not scored with paint but rather slicked with Vaseline. Vincent rubs Walter’s bare chest and face with it before Walter is called from the dressing room to the ring. That Vaseline is part of the boxer’s kit—along with his robe, satin trunks, gloves, tape, and icepack—carefully laid out on the bed back in the apartment and filmed by Kubrick in a slow, hovering pan. (A large jar of Vaseline also appears on the dresser of the boxer protagonist of Killer’s Kiss.) The fetishistic shot of the boxer’s things in Day of the Fight dissolves into a close-up of him regarding his face, artifact-like, in a mirror (Figure 12). This scene may be the strangest in Kubrick’s altogether strange take on the sports short. With Walter—now both viewer and thing viewed—we watch the man in the mirror go from coiffing his hair (so as to look his best for a fight?) to curiously tracing his finger across the lines of his eyebrows and then pressing it into the spongy tip of his nose, a nose that looks to have been broken before. Recall that Bruce Weber’s own boxing documentary movie debut is titled Broken Noses, signaling that form of facial disfigurement—sexy, it might be thought, in its way—as this sport’s calling card. “Before the fight, there is always that last look in the mirror,” muses the narrator of Day of the Fight, “time to wonder what it will reflect tomorrow.” In Cartier’s self-objectifying lingering farewell look we again see double—double in more ways than one. The boxer who once fought as “Twin Carter” now redoubles himself, all alone. Forms of replication multiply: two who are as one and one who here appears as two. We also see at once in Cartier’s reflection both what is and what may be, as he plies his own waxwork countenance with a hand that has the power to alter another’s. And therein is another double image, one of male vulnerability (not to say vanity) coupled with awesome brute force.17

Figure 12. The boxer’s magic mirror.

The mirror scene of Day of the Fight mirrors an even queerer looking double image from the “Prizefighter” photo-essay, which depicts the two twins face-to-face in profile, as Vincent again makes up Walter’s visage with that Vaseline (Figure 13). If the film’s mirror scene has a surreal, dreamlike aura, this one looks like an ecstasy. Literally so. The two boys, one another’s best, appear to be transported together outside themselves—and everything, as intimated by the lack of any background in the photo. The caption reads, “His expression reveals depths of fondness he has for his brother.” Whose “his” is this? Vincent’s? Walter’s? Who can say? On this account there is no need to tell them apart. For just before he enters the ring we are told how “every blow that Walter takes” is “going to land on Vince too.” “But,” the narrator deadpans, “they don’t talk about that.”

These mirror scenes involving the Cartier boys also double back to another of Kubrick’s Look pieces: a photo-essay I mentioned earlier on a baby’s first encounter with a mirror, published in the May 13, 1947, issue. The opening picture in this six-shot narrative sequence shows a tentatively smiling baby boy in his short pants waving or reaching out to what looks to him like a new playmate, one who replies in kind (Figure 14). Kubrick sets the angle of the shot so that we can’t see the front baby’s left arm: a perspective that creates the impression of two separate figures.18 Behind this baby boy lies a hairbrush: an intriguing single prop I take as a pointer to the all the scenes of male grooming forthcoming in Kubrick’s movies and not only Day of the Fight. In the third picture, the baby seems to offer his fellow that brush, only to see himself copied again. In the final picture, the child has turned away from the mirror, his mouth open in a wail of bewilderment or frustration. The evocatively pop-psych caption reads: “It’s beyond me, and I want no more of it. Mom—get me out of this fast.”19 The bare, artificial setting, the supersized mirror, and all the black box–like negative space that it creates suggest the controlled environment of an experiment—a not altogether benign one. It will be my argument here that Kubrick’s films never stop experimenting with their men and boys, with forms of masculinity and male identities.

Figure 13. Fraternal ecstasy.

Figure 14. Seeing double: A boy’s first look in the mirror.

To return to Day of the Fight, Walter Cartier, once in the ring at last, is matched with another “boy” (as the narrator calls him too): Bobby James, who is Black. The pair of welterweights makes for a different kind of play on sameness and difference. Compare again the fight film Spartacus, which will pit Kirk Douglas in the ring against the awesome Woody Strode, former college athlete and then professional wrestler. (The flamboyant Gorgeous George, another Kubrick subject for Look magazine, was a frequent opponent of Strode’s on the professional wrestling circuit.) Day of the Fight devotes two kinetically photographed and edited minutes of screen time to the fight itself, shot live by Kubrick operating a handheld Eyemo camera (which he thrust through the ropes right into the ring) and Singer using a camera on a tripod. Cartier wins with a knockout in the second round. A day’s work, reports the narrator, and there the film ends.

“Matched pairs of men will get up on a canvas-covered platform and commit legal assault and lawful battery,” the film’s narrator had heralded in his script’s most lyrical flight, “hammering each other unconscious with upholstered fists.” But Kubrick’s sports short, as we have seen, has two stories to relay at once. “One man … skillfully, violently overcom[ing] another”: “this is for the fan, short for ‘fanatic,’ ” we are informed in the opening segment of the film. That first, four-and-a-half-minute-long, tabloidlike introduction speeds us through the mechanics and also the annals of the sport, culminating in a shot of a boxing record book that fills the screen. A close-up of a hand belonging to Nat Fleischer, publisher of The Ring magazine and boxing historian, flips through the pages until we come upon the name and picture of Kubrick’s own “Prizefighter,” Walter Cartier. “What would his story be like?” asks the narrator, as the film cuts to a fight poster adorned with Cartier’s face attached to a lamppost. The film’s remaining twelve minutes are devoted to him. And it is around Cartier, plus his twin, that this other story unfolds: an inside story paired here with the public spectacle of the fight—a story about structures of bonding and male intimacy, of male doubling, but also coupling. A (brotherly) love story, if you will, to go with the nighttime call to battle.

Four years after he made Day of the Fight, Kubrick returned to the ring for his second feature film, Killer’s Kiss (1955): an atmospheric sports/crime pulp piece about another white, twenty-something boxer, soon to become a has-been, named Davey Gordon (Jamie Smith). This time there is no authoritative male voiceover to call him “boy,” the way that the narrator of Day of the Fight refers to Walter Cartier. But the puerile “y” tacked onto Davey’s name does the trick. The faltering welterweight is left to tell his troubled tale in a flashback that begins with the day of the fight—which itself begins with images that flash back all the way to Kubrick’s debut sports short. The first is a close-up of a poster with a photograph of Davey on it advertising his bout that night, just like the fight-night poster that presents Walter Cartier to us in the earlier film. The next shot, however, shows another of these posters in a puddle of rain, where this boxer’s image is forebodingly trampled underfoot. The second flashback to Day of the Fight occurs when we come upon Davey alone in his forlorn studio apartment, looking in a mirror. There, like Cartier, Davey tentatively pokes and pulls at his face as though it were made of putty, speculating about what it will look like after that night’s fight. “As hard a puncher as they come,” reports a TV sportscaster of this boxer; “but he’s been plagued by a weak chin”—“a glass chin,” it will later be recast.

Kubrick, who showed a flair for repetition from the beginning and quickly became his own chief influence, not only cites himself in this recycled mirror scene, but also adds to his repertoire of uncanny subjective shots. For here the boxer’s magic mirror is pasted with photographs. They picture his uncle and aunt (Davey appears to be an orphan: an intensification of Cartier’s circumstances, with his absent father and deceased mother), along with the family ranch in Washington State, from which he presumably came and to which he intends to return at the film’s end. What a curious image, when you think about it, this mirror adorned with snapshots, with freeze-frame mementos from another time. It layers and suspends there in a single look the present, past, and possible futures (one of which would be a return to the past, to the family home of sorts out west). At a further remove, we might also reflect upon the pictorialized looking glass as an early auteurist signature: another marker that for this director everything here looks back to the photograph—to how these fight films originate in the 1949 “Prizefighter” Look photospread Kubrick did on Cartier (and then did over again on the even more successful prizefighter Rocky Graziano). Both Cartier and Davey first appear in their movies in the form of photographs, in images of images. This is true for Cartier twice over. Recall that we first see his picture in a close-up of a boxing record book, followed by that shot of his fight night poster.

Figure 15. Davey, boxer with a “glass chin.”

There are photographs planted all over Killer’s Kiss. Reflective surfaces, too. Later, when Davey heads downstairs, we see him doubled in a gleaming row of metal mailboxes. But before that, in the scene that we were just considering, Davey goes from considering himself in his dresser mirror, to getting a glass of water from the sink over which hangs a second mirror, to then looking through the looking glass of a fish bowl. The reverse-angle close-up is Kubrick’s witty literal take on a “fisheye” lens (Figure 15). Bill Krohn sees this “deforming” image as making Davey look like “a battered pugilist”—even before the fight that night, which, no surprise, he loses.20 I see that here as well, along with a sense of both loneliness (Cartier has a twin brother and a dog; Davey’s only companions are a couple of goldfish) and confinement. But there is also something else to see reflected in this watery mirror image of the boxer with the glass chin. It’s a metamorphic image of dissolving and with it the possibility of becoming—one that is weirdly proleptic of the blank, expectant face of another Dave, astronaut Dave Bowman of 2001, in his amphibious-looking spacesuit and on the brink of his deep space transformation (Figure 16). Dave will metamorphose into the Star Child. But what of this earlier Davey? What may become of him, of this about-to-be-battered boxer, with the pliable putty face? “It’s crazy how you can get yourself in a mess sometimes,” he begins his story—the same old story (but then again perhaps not).

Figure 16. Dave, metamorphic astronaut.

Killer’s Kiss has a weak script. The acting is stilted. And the post-dubbed dialogue stutters in and out of sync with the image. But then there is, as we’ve been considering, Kubrick’s photography. The film’s feature length allows him to show off his own handheld camerawork, this time in two extended one-on-one fight scenes. The first takes place in the ring, where Davey is soundly beaten. As in Day of the Fight, Kubrick sticks his own hand through the ropes, rendering an array of shaky-cam close-ups that make us feel as though we are right there too. The rest of the world falls away. There are no establishing shots of the crowd in the stands here because there actually isn’t one. (Kubrick couldn’t afford the extras.) Martin Scorsese draws upon this visceral, right-there-in-the-ring-with-him effect, adding sprays of blood to the flying sweat, in his own tour-de-force boxing movie Raging Bull (1980), about Jake LaMotta, the one-time world middleweight champion. LaMotta and Kubrick’s Look photographic subjects Walter Cartier and Rocky Graziano were all friends and occasional sparring partners.

Kubrick’s cinema verité boxing footage is virtuosic and cinematically influential, and not only on Scorsese. This is something that commentators on Killer’s Kiss routinely remark, even those who have nothing else good to say about this bare-bones budget early feature. What also needs to be said is that Kubrick’s cinematic visualization of the fight is not only impressive but arousing too. It’s hard to imagine a more erotic shot selection from inside the ropes. Before the bell, Kubrick’s camera peers through the seated Davey’s legs all the way across the canvas to his opponent, Kid Rodriguez, in the far corner. This unusual crotch-shot point of view is also directly copped from Day of the Fight. In the extreme low angle frame that Davey’s bristly calves afford, we watch Kid Rodriguez’s trainer push in the boxer’s mouthpiece and then snatch away his stool. Rodriguez’s imposing form pops up in deep focus from between the still seated Davey’s splayed legs. The bell sounds, and the two dance around and court each other. Here it is “the two game boys” (as the TV commentator dubs them) matched in the ring, not the boys in the sheets and in the streets as in Day of the Fight, who double each other. Davey and his opponent come together hard in another striking shot that lops them off at their necks and knees, while centering on their bare, sweaty torsos in a tight male embrace, groin to groin. When they untangle their bodies from each other, Kid Rodriguez puts Davey down for the first of two eight counts. Another powerful blow hurtles Davey backward into the ropes, which is to say ass-forward into the frame and smack into our faces. “Go on home, Gordon; “You’re a bum,” someone in the crowd calls out. “You’re all through!”

“Surely boxing derives much of its appeal,” Oates insists, “from [its] mimicry of a species of erotic love in which one man overcomes the other in an exhibition of superior strength and will.”21 Kubrick might not have put it quite like that himself. But his Killer’s Kiss proffers the encounter in the ring between the dominating young Kid Rodriguez and the overmastered veteran Davey as pornography for the morose crime boss Vincent Rapallo—note the reuse here of Walter Cartier’s twin brother’s name—and his moll Gloria Price. The Jamaican-born, mixed-race actor Frank Silvera, the only real professional in the cast, plays Vinnie in darkening makeup. Irene Kane, who had done some modeling for Vogue, is the bottle-blond Gloria.22 Along with the washed-up prizefighter Davey, they constitute the dismal masochistic erotic triangle of a movie to which Kubrick, when he rewrote Howard Sackler’s first-draft screenplay, gave the working title The Nymph and the Maniac.23

Gloria, who lives in a one-room apartment directly across the way from Davey’s, works as a “hostess” at Pleasure Land, the taxi-dance hall that Vinnie runs in Times Square. The sole windows in Gloria and Davey’s matching apartments face one another, affording their inhabitants nowhere else to look. Early on in the film we see that they are the unknowing (or perhaps not so unknowing) objects of each other’s rear-window voyeurism. In Hitchcock’s movie Rear Window, which came out the year before Killer’s Kiss, the photographer Jeffries (James Stewart) doesn’t become aroused by his glamorous girlfriend Lisa (Grace Kelly)—so notes Laura Mulvey in her influential schematization of the cinematic gaze—until she leaves his apartment and crosses over to the other side of the courtyard: that is, into the field of vision for his scopophilia.24 Kubrick reworks this arrangement by placing Gloria (his poor man’s Grace Kelley), over there on the other side from the beginning. Kubrick further plays with the erotic gaze, routinely indicated, following Mulvey, as male, by having the woman steal the first long, lingering look, one that also takes in the boxer’s backside. Gloria becomes the object of his gaze that night, after he returns home from the fight. We see Davey sitting alone in the dark and shirtless once again, staring at Gloria, who has taken off her blouse.

Still later that night, Gloria’s scream summons Davey from his place to hers to save her from the rapacious Rapallo’s unwelcome advances. The next morning she recounts her life story: a sorry family drama steeped in Freudianisms (incestuous desire, sibling rivalry, and the like). Kubrick sets Gloria’s voiceover to a bizarre solo ballet interlude on an empty stage by his then wife Ruth Sobotka, a Viennese-born dancer, painter, actor, and set designer, who moved through the New York avant-garde art scene. She figures Gloria’s ballerina older sister, Iris: the image, we hear, of their mother and their daddy’s favorite. We also now learn that Gloria, like Davey, is now an orphan. Parallel edits earlier in the film of them readying themselves for work—the boxer and the low-rent dancer are both professional entertainers, the kind who offer up their bodies for others’ pleasure—have already established them as another of the film’s multiple sets of doubles. These paired scenes culminate in Gloria and Davey arriving downstairs, with their coats and bags (hers a purse, his a duffle), at precisely the same moment. They silently exit the courtyard to the street walking side-by-side in a way that harks back to the Cartier twins. Even as they go their separate ways, the parallelism continues. Davey waits in the locker room and has his hands taped up by his trainer. Then his manager (in another replay of Day of the Fight) glazes Davey’s face and bare chest with Vaseline before giving him a prefight rubdown. I find these silent, dutiful scenes of handling and preparing the fighter’s body among the most intensely intimate male images in all of Kubrick. In between those male ministrations, the film cuts to Gloria alone in the dressing room at Pleasure Land. She is also shown undressed, getting ready in front of another mirror for her own night’s work. A close-up of the dresser strewn with her makeup, tweezers, brush, and high-heel shoes recalls that fetishistic slow pan across the boxer’s kit laid out on the bed in Day of the Fight.

Once Gloria is out on the floor, Vinnie roughly cuts in on a soldier with whom she has been dancing to steal her away to his office so that they can watch Davey’s bout on TV. At the end of the film, Davey and Vinnie will, in another of Kubrick’s race-inflected duels, face off. That fight Davey manages to win. But here the film intercuts the beating that Davey takes in the ring with shots of Vinnie and Gloria in an outward-facing embrace, their eyes locked, not on each other but instead on the boxers. Socially censured in many quarters and on occasion even outlawed, boxing has never altogether shed its underworld association with organized crime and vice trades such as gambling.25 This sport’s allure for Vinnie is another aspect of his sordidness. But the film shows Gloria no less transfixed than he is by what she spies on his television, with its small, round, peephole-like screen. The killer’s kiss in the ring—the smack that lays out Davey for the count—leads to Vinnie’s lip lock with Gloria (“Her soft mouth was the road to sin-smeared violence,” cries the movie poster), and then the screen fades to black.

Looking back on Killer’s Kiss in an interview many years later, Kubrick lamented the “slight zombielike quality” of the acting.26 The awkwardly postsynched dialogue mentioned earlier may be blamed in part for that effect. But the robotic performances feel right for a movie whose climax is staged in a Garment District mannequin factory and warehouse. It is there, in the second fight scene of Killer’s Kiss, that Davey and Vinnie battle to the death over its femme fatale, this pearl of great price. Kubrick abandons the gritty realism of the film’s first fight scene for a warped expressionism evocative of Orson Welles’s The Lady from Shanghai (1947), though he replaces the multiplying mirrored forms of that movie’s famous funhouse sequence with heaps of plastic molded ones. This principle of reduplication, first iterated with the shots of Davey doubled in not one but two mirrors at home, has been building on itself throughout the film. Take the kitschy drawing of the two guffawing clowns hanging in Vinnie’s office, in which Vinny sees himself mirrored as the object of derision and so he flings his glass at it. Or the two drunken, madcap Shriners who steal Davey’s scarf, causing him to give chase and thus saving him from Vinnie’s two henchmen, who then mistakenly target and kill Davey’s manager Albert instead. The hoods corner the doomed man in a dead-end alley, next to a huge “Notice” that declares “No Toilet.” (Not a good sign in a Kubrick movie.) This compulsion on the part of the film to make everything double is now, in its climax in the mannequin factory, hyperbolized in a stockpile of nude human figurines and unattached body parts: heads, hands, legs, trunks, set out in orderly rows or amassed in overflowing piles. Its humanoid mise-en-scène is prefigured earlier in the film by a wonderfully strange Times Square storefront montage that includes a mechanical Santa Claus sticking out his tongue to lick the candy apples that he holds, one in each hand, and a wind-up plastic naked baby paddling around in a bowl: artificial persons in a surreal city.

“I gotta get out of here,” Vinnie murmurs to himself, once he takes stock of where he is. But Davey, whom we watched manipulate his own features as though they were putty—Davey, the boxer with the glass chin—turns out to be made of stronger stuff. He fits in better than Vinnie does among these abstract, pseudo-bodies. Davey first crouches for cover, lining up himself in a row of male heads all facing the same way. And then he defends himself against the ax-wielding Vinnie by prosthetically arming himself with whatever plastic dummy body part he can lay his hands on. (A Clockwork Orange pornographically tropes on this, first in the female-form fiberglass furniture of the Korova Milk Bar, and then Alex’s murder of the Cat Lady with a giant sculptured cock and ass.) Eventually Davey takes up a spearlike hooked window pole. He stabs Vinnie to death with it, gladiator-like, as the film shock-cuts to a shattered mannequin face. Catherine Malabou, working at a conjunction of philosophy and neuroscience, credits humans with brains that are plastic.27 Kubrick renders synthetic men in glass and plaster-molded parts.

And it is a world of plastic people who pose as the impassive audience for this final struggle between men, an audience that went missing from Davey’s first fight back in the boxing ring. Not even Gloria is there to see it. After Davey’s botched attempt to rescue her in the scene before, she remains tied up in Vinnie’s nearby hideaway. (The film has prefigured this too, in the form of a doll tied up to the bedpost back in Gloria’s studio apartment.) Some of the mannequins are male; others are ungendered. Most of them, however, are female. Indeed, there are more female forms here than anywhere else in Kubrick, until we arrive at the orgy scene in Eyes Wide Shut. These mannequins are the only spectators for Davey and Vinnie’s mortal faceoff, and they are a mute, unimpressed crowd. Some dummy eyes seem trained on the combatants, others not. But as things, none of them sees anything. Their presence as blank witnesses undermines the performance of masculinity for anything at all—literally any “thing.”28

This stunning scene makes for a queer penultima to what may look like the most conventional Hollywood ending in Kubrick. Killer’s Kiss concludes with Davey waiting for Gloria at the old Penn Station, where they are to catch a train that will carry them far away to a new life together at his uncle and aunt’s horse ranch in Washington. The film has thus returned to where its story began (this time-loop trick will be repeated in Kubrick’s Lolita), which is with this very scene of Davey nervously pacing at the train station, two small pieces of luggage at his feet. As he waits, he tells his tale in a flashback that (to repeat myself) flashes us all the way back to Kubrick’s first boxing film. In its seedy noir romance replay of Day of the Fight, Killer’s Kiss recasts the self-sufficient, idyllic male “couple” of that sports short into an agonistic heterosexual love triangle and increases the number of character parts in the revamped ringside drama. One example: the prefight ritual of oiling the boxer’s body is performed in Killer’s Kiss not by his twin but by his manager Albert—though, as we saw, he himself is tragically taken for the boxer by Vinnie’s thugs, who murder him instead. Another is that it’s Gloria who, after Davey has chased Vinnie away from her apartment, makes breakfast for him—just as the other Vincent, Vincent Cartier, does for Walter in Day of the Fight. This redistribution of roles is necessary for Killer’s Kiss to enact its boxer meets, saves, and wins girl plot, however ham-fisted it is.

But what in the end does this boxer have to show for himself in the exchange of the fraternal devotion of a male double for a woman? Well, Gloria does not leave Davey alone at the station. She at last arrives and dashes across the platform into his embrace. They kiss. Yet the train to Seattle has already left, while Gloria, unlike Davey, has shown up empty handed. And to invoke Rear Window once more—specifically, the verified “feminine intuition” of Grace Kelly’s Lisa—what woman would really be intending to go off anywhere with no bag, “without packing make-up, clothes, and jewelry”?

A parting shot: Irene Kane, the actress who plays the slightly tomboyish Gloria Price in Killer’s Kiss, remembers Kubrick as (Hitchcock-like) “all for sex and sadism.” She also recalls how Kubrick talked her into the role—her first in a movie—by saying that he “loved my voice,” “a little-boy voice,” as it was described.29