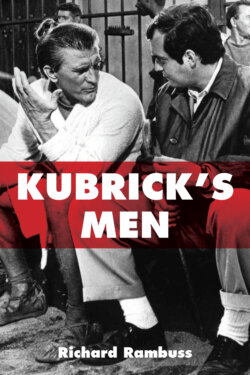

Читать книгу Kubrick's Men - Richard Rambuss - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Photography

ОглавлениеBoxing is the most directly violent of athletic contests, the closest to a human blood sport. It’s the sport least like a sport and the closest to combat. To injure, even incapacitate, is the aim. The chief target, Joyce Carol Oates points out in her entrancing book On Boxing, is the brain.1 As in war, a “killer instinct”—the phrase originates in boxing—is prized. But the Sweet Science of Bruising can also be stylish, look sexy. Kubrick doesn’t shy away from this contact sport’s bared body, dark machismo glamor; his camera indulges in it. That Cartier is male-model handsome (if never quite a champ) doesn’t hurt. Kubrick makes the most of those chiseled good looks in the story’s lead picture, a three-quarter shot printed as nearly a full page (Figure 2). We come upon the fighter in the locker room. He is posed on a bench against the grid of a concrete brick wall, waiting for the summons to the ring: a portrait of brooding male anticipation. Kubrick’s movies, starting with Day of the Fight, are full of images of men on the edge, waiting out some inexorable countdown. Cartier’s manager, the legendary Bobby Gleason, is to the right of him in shirt and tie, making Cartier’s semi-naked body seem more naked. Kubrick shoots the boxer’s torso from below, monumentalizing the male form. An unseen overhead flood throws light across the expanse of Cartier’s sculpted, hairless chest and shimmers on the black leather boxing gloves resting in his lower lap. The gloves touch, and the chiaroscuro effect there outlines, stigmata-like, a heart that is also a hole (Figure 3). As Roland Barthes would say, that detail—this photograph’s punctum—is what pricks, what bruises. Kubrick’s wistful boxer looks like a fighter and a lover.2 Cartier’s chiseled face is raised and slightly tilted left, as though, starlike, to find his light. Strong shadows set off his angular jaw and steep cheekbones. Dark planes render his heavy browed, deep-set eyes deeper—or masked, even made-up.

Kubrick’s hard-contrast black-and-white photography has been compared to that of the noir New York photojournalist known as Weegee, who is an obvious influence on the young Kubrick. This particular photograph, though, makes me think ahead, impressionistically, to Robert Mapplethorpe and some of his statuesque male nudes and sexual exhibitionists. Again, it’s that sensuous detail of the plush black-on-black of Cartier’s crotch: black leather, black satin. This has the feel of what Freud terms a media fetish: that is, the fetishism of materials—leather, velvet, rubber, latex—of which Mapplethorpe was an artist-connoisseur. And it’s not just that detail: everything about Kubrick’s photograph—presented as photojournalism and yet as controlled in its own way as Mapplethorpe’s studio portraiture—strikes me as dark and hintingly kinky. Both Kubrick’s photo-essay and his documentary treat boxers as a breed apart among men, as somewhat fringe figures (“There are six thousand men like these in America.” “Why do they do it? … Where do they come from?” queries the film’s narrator), even as their portfolio of images from Cartier’s life mixes in domestic interludes. The main event, however, is in the ring, which, thrills another headline in “Prizefighter,” is “filled with slashing blows of leather on flesh.” The picture-stories presented in Look were collaborative pieces. As the photographer, Kubrick may or may not have had a hand in crafting that stroke of pulpy prose. But the fascination of his early work with boxing and its drama of punishment between the ropes is nonetheless of a piece with the various male sadomasochistic scenarios to come in his films.

Figure 2. Prizefighter Walter Cartier’s chiseled good looks.

Figure 3. Detail: the punctum.

As for the fight scenes in “Prizefighter,” they cut both ways. Cartier prevails in one of the bouts pictured, but he loses the other on a TKO. Another thing about Kubrick’s fighters—not only his boxers, but also his soldiers, and indeed just about all his men—is that their machismo, however ramped up, is hardly indomitable. We see them take their beatings not just give them. In a way that bears further comparison to Mapplethorpe, the more interesting objectivity effects in Kubrick tend to accrue around his male figures and not really so much the female ones, who, in any case, are almost always secondary, if present at all. That is in part because the kinds of narratives that Kubrick’s films unspool—typically of clashes and journeys—are staked to a vulnerable masculinity, to male identities that are treated as inherently pliant, physically no less than psychologically. This points to a general difference between Kubrick and Mapplethorpe as male portraitists. Whereas what Richard Meyer refers to as the “stilling gaze” of Mapplethorpe’s camera renders its male subjects and male scenes in the stasis of a “Perfect Moment,” Kubrick’s men tend toward a masculinity that is metamorphic, a masculinity that is pliable or in flux.3

Speaking of photographers known for their male portraiture, another, sunnier image in “Prizefighter” looks to me like something that Bruce Weber, working in one of his romantically retro modes, might have taken. The shot is of Cartier, again shirtless, though this time not in repose but rather with his corded muscles flexed in exertion on an afternoon outing to Staten Island with a girlfriend (Figure 4). “Rowing out to a friend’s sailboat,” blazons the caption, “emphasizes long, powerful muscles that give him punching power.” Weber is known for his alfresco male youth physique photography, including his Abercrombie and Fitch “Bear Pond” fashion shoots of athletic boys cavorting in bucolic settings with big dogs and each other. Occasionally some girls are mixed in, but even then Weber’s images feel homoerotic. Just so Kubrick’s hunky picture of Cartier in the rowboat. Its caption doesn’t remark the presence of the woman to whom he’s turned his back—though not to gaze out at Kubrick’s camera and thus also at the viewer, but rather to look down at his own powerful hands gripping the oars. Cartier’s female companion (Dolores Germaine) is named in the caption for another, much larger photograph of the two on the same page, though it notes that the boxer “has no No. 1 girl friend.” Cartier, again presented sculpturally in the foreground as a beautiful object to be admired, dominates this image too. His outsized recumbent head looks like a Brancusi “Sleeping Muse”—only a male one.

Two other, smaller photographs complete this single-page spread on the boxer at rest and at play. They are placed at the bottom, where they follow in a row after the rowboat photo. The friend’s sailboat toward which Cartier is there pictured sculling comes back in the row’s last photograph as a toy sailboat that he fixes at home for his “little nephew and leading rooter.” This playful intergenerational male scene is staged in a way that quotes but reverses the brooding locker room picture of Cartier with his much older manager. This time the bare-chested figure on the left is the nephew, with Cartier now on right in the white shirt. The snapshot that comes between the two boat pictures singles out Cartier for once alone, while now casting him in the role of “rooter,” as he cheers on the Boston Red Sox at a baseball game in Yankee Stadium. In Bruce Weber’s “Bear Pond” idylls, the clean-cut male faces and toned bodies seem, in their invariable, fairly machinic perfection, interchangeable. Indeed, Weber likes using brothers, especially twins, as models. Kubrick too, we will see, is attracted to male doubles in their formal, objectifying capacity. For now, note that here it is the man/boy pictorial arrangements that serially repeat and the boy’s toys that are interchanged.

Figure 4. The prizefighter at play.

Admittedly it is whimsical, perhaps even perverse, to bring Mapplethorpe and Weber glancingly into a treatment of Kubrick’s photography. I do so more as an opening gambit to reset the stage, to vary the frames of reference for thinking about male subjects and/as objects in Kubrick than to suggest direct lines of influence between artists. But it is notable that the homoerotic photographer Weber duplicates Kubrick in choosing an attractive, sensitive, young boxer as the subject for his own filmmaking debut: Broken Noses, a wistful, mostly black-and-white 1987 documentary about the coltish former Golden Gloves lightweight Andy Minsker. A still boyish coach and father figure, Minsker (shirtless through much of the film) runs a boxing club for ten- to sixteen-year-old boys (also often shirtless). Weber exchanges the boxing ring for the wrestling mat in his 2000 film Chop Suey, partly a coming-of-age story about a teenage wrestler and model named Peter Johnson, Weber’s own muse at the time. Boxers and wrestlers, along with bodybuilders, were among the first male pinups.4 Weber is mining that tradition here, as well as in his commercial work for Abercrombie and Fitch. These same masculine icons also crop up throughout Kubrick’s Look work.

In between his two athlete homages, Weber made another highly stylized biographical documentary with a male subject: Let’s Get Lost (1988), which is about the jazz trumpeter and singer Chet Baker, a dreamboat himself back in his youth. Kubrick’s own enthusiasm for jazz—he played drums in a swing band in high school—led to assignments for Look like “Dixieland Jazz is ‘Hot’ Again.” This June 6, 1950, entertainment piece has more of a sociocritical edge than is usually evident in Kubrick’s work for the magazine. It intermixes images of Black musicians playing to well-dressed white audiences in New York nightclubs with scenes of those musicians back in their own homes in New Orleans. The juxtaposition suggests that the Dixielanders themselves weren’t reaping much in the way of reward from the revival of their music. In one image from this shoot, Kubrick poses himself behind the drum kit—the white guy in a Black band—and looks right into the camera, with eyebrows arched (Figure 5). Kubrick also shot pictures for the magazine of jazz pianist and composer Erroll Garner, bandleaders Vaughn Monroe, and Guy Lombardo, and clarinetist Pee Wee Russell. Frank Sinatra and Leonard Bernstein were among his other subjects. And Kubrick got to photograph Montgomery Clift in his New York apartment for a story that ran in the July 19, 1949, issue of Look as “Glamour Boy in Baggy Pants.” It is composed of nine pictures of the man whom the Barbizon Models of New York had just named America’s Most Eligible Bachelor. In an interview many years later with Michel Ciment, Kubrick singled out this piece about the closeted actor as one of more interesting “personality stor[ies]” that he got to do at the magazine.5

Athletes, as I’ve been suggesting, appear to have been another Kubrick forte for Look. In addition to Walter Cartier, he photographed baseball stars Don Newcombe and Phil Rizzuto, along with decathlon champion Irving Mondschein, among others. Then there are his pictures of sports figures with a twist, such as the flamboyant professional wrestler Gorgeous George, dubbed “the Human Orchid” for his golden locks, fancy drag costumes, and practice of perfuming the ring upon entering it. Or take Kubrick’s 1947 piece “Baby Wears Out 205 lb. Athlete.” It playfully infantilizes a strapping ex-marine and Carleton College football player, Bob Beldon, as he tries to imitate and keep up with an indefatigable toddler. This is just one of the many man-to-boy stories in Kubrick, stories whose apotheosis will comes in 2001: A Space Odyssey, when astronaut Dave Bowman returns home as the Star Child.

Figure 5. Kubrick on the drums down in New Orleans. (Stanley Kubrick, photographer, LOOK Magazine Photograph Collection, Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, LC-L9-50-W99-C, no. 29. Used with permission of the Stanley Kubrick Film Archives.)

We see from Kubrick’s marine jock and toddler photo-series that he had a flair too for photographing children. Here the effect is comic. Kubrick’s unpublished “Tale of a Shoe-Shine Boy,” also from 1947, is a Dickensian epic. This is another one of Kubrick’s day-in-the-life visual essays. Its subject is a twelve-year-old from Brooklyn named Mickey—fetching enough to be a child actor—who shines shoes to help support his nine younger siblings. Kubrick follows Mickey from the streets where he works to the tenement building rooftop where he tends his homing pigeons. He also shows Mickey hitting both his schoolbooks in the library and other boys in neighborhood boxing ring (Figure 6). In between his “Baby Wears Out Athlete” and “Shoe-Shine Boy” stories, Kubrick landed the August 5, 1947, cover of Look with his shot of a little boy gleefully dousing himself in the shower to cool off from the summer heat. The following year Kubrick photographed five-year-old miracle boy Wally Ward, who recovered from his infant paralysis to play with a football and spring handstands.

Figure 6. Boy boxers. (Stanley Kubrick for Look magazine. Museum of the City of New York. Used with permission of Museum of the City of New York and Stanley Kubrick Film Archives.)

I am cherry-picking male images and storylines here, of course. In the five years that Kubrick worked at Look, he showed that he could frame an interesting, artful shot of nearly anything and anyone. He took thousands of pictures for the magazine, with more than nine hundred of them published in its pages.6 Kubrick’s assignments run the gamut from circus performers, including a tattooed man sporting enormous iron nipple rings, to showgirls and socialites; from rising star Doris Day to aspiring actress Betsy von Fürstenberg (“The Debutante Who Went to Work”); from the co-ed dating scene at the University of Michigan to nuclear scientists at Columbia; from “A Dog’s Life in the Big City” to a baby boy’s first look into the mirror.

Female nudity figures throughout Kubrick’s movies.7 There’s a foretaste of that here in his Look photography: von Fürstenberg reading a script in her negligee; an undraped female sitter in front of an art class at Columbia; a man contemplating an enormous female nude hanging in a picture gallery; New Yorker sophisticate cartoonist Peter Arno in his studio with his own personal naked model, whom Kubrick shoots full-on from behind (Figure 7). The unexpected discovery is all the male bodies in states of undress in Kubrick’s work. If “Art” serves as the cover for many of the naked female bodies in his photography, the alibi for nearly all of the beefcake here is sports.

Figure 7. New Yorker cartoonist Peter Arno with model. (Stanley Kubrick for Look magazine. Museum of the City of New York. Used with permission of Museum of the City of New York and Stanley Kubrick Film Archives.)

Figure 8. “Glamour Boy” Montgomery Clift.

Kubrick’s Look work also presents more intimate male images, like snapshots of the thirty-year-old, bare-chested Leonard Bernstein looking fit in his bathing trunks. Or Montgomery Clift sprawling on the bedroom floor in his boxer shorts, sucking on a bottle of wine (Figure 8). Another of Kubrick’s bedroom pictures presents boxer Walter Cartier in nothing but his jockey shorts, yawningly just out of bed (Figure 9). His arms-akimbo pose echoes that of Arno’s nude female model, connoting display, access. A second young man still lies there in Cartier’s bed, wearing no more (perhaps less) than the boxer in his briefs. He too faces us, but his eyes are demurely closed. This private, behind-the-scenes “candid” is carefully composed: an erotic planar geometry of intersecting, if just now no longer touching, semi-naked athletic male forms. Thomas Waugh has searchingly analyzed the ways in which the male athletic photograph, ever since its late nineteenth-century emergence as a new genre, has “accommodated the homoerotic gaze.”8 Kubrick’s own sports photography not only accommodates that gaze, it courts it.

Kubrick retraced the day-of-the-fight storyline of “Prizefighter” in a February14, 1950, photo-story for Look about the more famous middleweight Rocky Graziano subtitled “He’s a Good Boy Now.” Kubrick’s camera follows a naked Graziano first into the ringside doctor’s examination room and then the showers (Figure 10). Look didn’t publish these locker room nudes of the one-time world champion, but it’s something that Kubrick took them, just as he did of Walter Cartier. Kubrick’s earlier photospread on Cartier reports that this fighter is headed to law school if he soon doesn’t make it to the top in the ring. But when Cartier (who died in 1995) left the sport it was instead for acting, including a part in Somebody Up There Likes Me, Robert Wise’s 1956 Oscar-winning drama about Graziano’s hardscrabble life. Handsome Paul Newman plays Graziano.

Figure 9. Boxer in briefs.