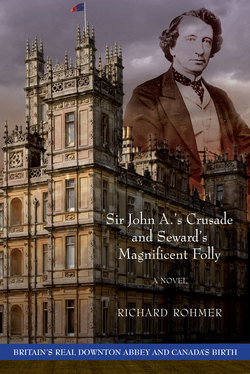

Читать книгу Sir John A.'s Crusade and Seward's Magnificent Folly - Richard Rohmer - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

2

ОглавлениеDecember 10, 1866

St. Petersburg

The even gait of the pair of sinewy young horses gave the sleigh that familiar gentle back-and-forth motion, a movement that had always comforted Edouard de Stoeckl, especially when he was in the incredibly beautiful St. Petersburg. And doubly so on this crisp, frigid morning as the Imperial sleigh carried him over a blanket of yielding fresh snow toward the massive building that housed his master, the Tsar’s powerful Foreign Minister, Prince Gorchakov.

De Stoeckl’s ship had docked in the bustling ice-rimmed harbour at high noon the day before. Now he was on his way from his hotel, the Grand, to the Winter Palace to pay his respects and make a preliminary report to Prince Gorchakov. He expected that the Prince would provide him with an itinerary and the time of the meeting he hoped to have with the Tsar to discuss a most pressing topic.

The Tsar’s Washington plenipotentiary sat huddled under a bulky blanket, the high collar of his ankle-length sable coat turned up to cover his neck and face, the flaps of his matching fur hat pulled down to protect his ears from the crackling cold. For the moment, de Stoeckl was thoroughly content.

The pleasurable sights that his squinting eyes took in had driven from his fretting mind — at least for the moment — his nagging concerns about the meeting with Tsar Alexander and his pompous brother, the Grand Duke Constantine, to discuss the Empire’s most questionable possession, the remote, and because none of the dignitaries who would be at the conference with the Tsar had ever been there, the almost fictitious, lands and waters thousands of miles to the east and across the North Pacific known as Russian America.

De Stoeckl could hear the soft, snow-muffled clopping of the horses’ hooves mixed with the tinkling of myriad bells on the polished leather harnesses strapped over purple blankets emblazoned with the Imperial double-headed eagle. Beyond the swaying, high back of the sleigh driver, he could see the massive rumps of the ebony horses, tails twitching, swaying in unison like a pair of locked pendulums. De Stoeckl could see their alert, pointed ears and the billowing white clouds of breath that came back from their snorting, puffing heads. Above was a crystal-clear blue sky unblemished by even the hint of a cloud, the horizon broken only by the towers and roofs of the massive buildings that fronted the broad approaches to the looming gates that opened into the high-walled courtyard of the Winter Palace.

This was a sublime moment for de Stoeckl, short minutes that captured his heart’s desire, a yearning that had developed during his seemingly interminable posting in that power-mad, politically corrupt bastion of new republican democracy — Washington. Oh, to be back in St. Petersburg, or, if not that magnificent capital of the Russias, then Paris or London or some other cultured, sophisticated principal European city. Anything to get out of Washington. But de Stoeckl knew that he would never have a posting in St. Petersburg.

He had long since decided that when he retired — perhaps in two years’ time when he was sixty — he would take his young American wife to live in Paris. She could accept the “City of Lights” but could not abide the prospect of living in a place such as St. Petersburg, which was so different from her beloved America. She had long since learned from the difficult experiences of past visits to St. Petersburg that apart and away from the glittering, sumptuous façade of the Tsar’s court and the palaces that contained it, the real Russia, the world she would have to live in if her Edouard had to return to a post or retirement in the capital, would be intolerable. She would be thrust into totally different culture and language, as would their two daughters, both in their early teens. No, his wife would have none of it. Martha de Stoeckl had firmly refused to join her husband for this visit to St. Petersburg, even though it meant that she and the girls would be separated from Edouard at Christmas. She had had enough of the days and nights of seasickness through which she suffered during the wretched Atlantic crossings. And she had had enough of the boring hours of sitting and waiting while her husband attended to the volume of business at the Foreign Ministry or at the several other ministries that did business with the government of the United States, or with firms engaged in trade with the Americans.

Boring? Being in St. Petersburg for her was like being in prison. Even when Edouard was with her during those weeks of hotel confinement she was bored and unhappy. There was little for them to talk about except to wonder how the children were getting on back in Washington with their nanny or for de Stoeckl to go on about the various events that had happened during the day, rattling off stories about people — always men — whom she had never met. His Excellency so and so, Minister this and that, His Royal Highness The Prince of something or other.

So gradually their time together became a time of silence. He would read and shuffle through his papers while she would attack her needlepoint. It followed, or so she thought, that with his advancing years Edouard’s interest in touching her, offering acts of physical intimacy, or expressing words of affection had all but disappeared. The once glowing light of love had dimmed, choked off by that powerful, depressing force that enveloped them both — boredom with each other’s minds and bodies. While she silently blamed his advance into old age, de Stoeckl told himself that she had chosen frigid abstinence, probably out of fear of another, and at this late time, a much-unwanted pregnancy.

As his thoughts of Martha coursed through his mind — but only briefly — Edouard de Stoeckl’s shoulders moved in an involuntary shrug under the smooth dark sable. That rich fur was a mark of his senior rank in the hierarchy of power that flowed across the Motherland as an emanation of the man upon whom he had been summoned to attend, Alexander, the Tsar of all the Russias.

The shrug was the response to the point at which his rueful thoughts about his unresponsive mate intersected with the image of another woman, a raven-haired beauty whose face forced itself into his mind, causing the features of his wife to disappear the way a magician disposes of the presence of a person behind a puff of stage smoke.

There in his mind’s eye lay Anna, her willowy pink-white body silhouetted against the silk sheets, her full lips opened with invitation as her arms reached out for him. What an unbelievable night of lovemaking — beyond any experience de Stoeckl had ever had or believed could be had. He shook his head ever so slightly as his mind reeled with the incredulity of the passion so fresh in his memory. He had torn himself from Anna’s amorous embrace in order to bathe, trim his beard and mustache, dress, and be out of the Grand Hotel and into the waiting sleigh to be carried to the Foreign Ministry.

Would Gorchakov notice how haggard he looked? Would the Prince speak to him about his apparent lack of sleep? Behind the sable collar his lips parted in a smile as he decided that his response, if queried, would be that he had spent a fitful night worrying about the issues of the Russian America decision and about his ability to comprehend and adequately respond to the questions that might be put to him by His Imperial Majesty or His Royal Highness. It would be highly inappropriate for him to announce that his condition was the result of a night of frantic love-making. On the other hand, if de Stoeckl were to make such an admission, Gorchakov might look at him with reproof but would undoubtedly conceal a surge of jealousy behind his mask of shock.

De Stoeckl was rudely jolted from his thoughts by a sharp, pungent, heavy smell that blasted, undiluted, full into his fur-covered face, penetrating the sable with the ease of a sharp sword cutting soft lard. The horse on the left had noisily passed a packet of stench that would either sober or strangle any normal mortal. For his sins, de Stoeckl prayed that the animals felt healthily relieved.