Читать книгу Sir John A.'s Crusade and Seward's Magnificent Folly - Richard Rohmer - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

3

ОглавлениеDecember 11, 1866

Newbury, England

“I’m concerned about what those bloody Americans are up to, I must say. That wretched fellow Seward and his Manifest Destiny thing.” Lord Carnarvon took a long pull on his after-dinner cigar. Through the cloud of pungent smoke, he politely asked his Canadian guests, “More port, gentlemen? Monsieur Cartier? No. Mr Galt, a soupcon? Yes. And of course, Mr. Macdonald. Your glass is empty.”

“The port is exquisite, Your Lordship.” John A. Macdonald smiled as he held out the silver goblet to be refilled by their host, thirty-five-year-old Henry Howard Molyneux Herbert, fourth earl of Carnarvon and the Colonial Secretary in the unstable government of the day.

The Colonial Secretary, recently in office in succession to Edward Cardwell, was most anxious to grasp what was going on with the Canadians and the Maritimers at their private proceedings in the Westminster Palace Hotel. It was inappropriate for Carnarvon to intrude directly on the meetings. He was already dedicated to the proposition of Confederation of the British colonies in North America. That past summer, during the transitional period of assuming the Colonial Secretary’s post, the young earl had concluded that his most important objective would be to strengthen, as far as practicable, the central government of British America against the excessive power or the encroachment of the local administrations.

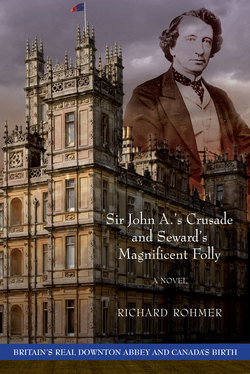

What better way to have news of the proceedings than to invite the three Canadian leaders — all of whom he now knew through meetings and correspondences — to travel down to Newbury by mid-afternoon train and have dinner and spend the night at his family’s hereditary estate, Highclere Castle?

This magnificent stone edifice stood majestically encircled by gently rolling parkland broken by stands and copses of trees. The first viewing of the castle had made a deep impression on the awestruck colonial trio as their two-horsed coach approached Highclere through massive iron gates and proceeded down a red cobblestone lane lined with towering oaks. Their awe had continued even after the warm greeting by the youthful minister and his lovely and even much younger chatelaine. After being shown by servants to their respective rooms, the Canadians had been taken by their host on a tour of the vast mansion with its many wood-panelled rooms, most of them enriched with splendid paintings of Carnarvon’s numerous ancestors as well as past and present members of the Royal Family.

“Dinner is at seven for eight,” Carnarvon had advised his guests as he guided them at long last back to their bedrooms. Knowing that formal dress was required, the colonials had come prepared.

“About this ‘Your Lordship’ business,” Carnarvon said as he put the port flask on the spindly, lacquered table that stood between the deep, soft, dark-leather chairs clustered around the roaring fire in the library. “I think it would not be untoward, gentlemen, if in private circumstances such as these you might be good enough to call me Harry. After all, we’ll see a great deal of one another in the next weeks as we work toward the legislation you need for the creation of a unified British North America. So I would be obliged if, in view of my comparative youth and” — he grinned — “inexperience, you called me by that name.”

Macdonald, Cartier, and Galt, each looking nearly old enough to be Carnarvon’s father, shifted uncomfortably in their chairs as they considered how to respond to this gracious, totally unexpected request. It would be up to John A., the chairman and leader of their London Conference, to respond.

As he listened to Carnarvon, Macdonald sipped his heavy, sweet port. He was already relaxed after several before-dinner scotch whiskeys and the superb Loire Valley white wine served flowingly with the pheasant. The lanky minister had his response at the tip of his eloquent Scottish Canadian tongue. He looked at his host, a man of fine-cut English aristocratic features, his wavy brown hair and full black Victorian beard carefully groomed, his dark brown eyes soft and sincere, his frame slight in build and much shorter than his tall, gangly self.

“That is a most gracious offer to us unworthy colonials, sir.” Macdonald’s Scottish brogue was soft. “On behalf of my respectful colleagues and myself, even though we are not necessarily in comfort about the matter, we accept, Harry. But only on the condition that you call us George, Alex, and John A.”

“Agreed!” Carnarvon laughed. “Now tell me, how is your conference going?”

The pugnacious, square-jawed Alexander Galt, his large nose and high forehead flushed pink from the food, wine and fire, said, “If it please Your Lordship —”

“Harry.”

“Harry … before we discuss how the conference is going, what’s all this about what the bloody Americans are up to?”

“Well, we are all much aware that their anti-British animosity cup is running over.”

“That’s a mild way of putting it, considering that the bloody Irish American Fenians want to kill us all,” Macdonald muttered as Cartier nodded his head in agreement.

Carnarvon pulled a handkerchief out of his left sleeve, staunched his slightly dripping nose, then continued. “I’ve received word of a Washington rumour that may be significant. Or, it may not. I’ll let you people be the judges. But first things first. The conference. Is it going well?”

Macdonald looked toward the leader of the government in Lower Canada, the white-maned, excitable George Cartier. A slight nod invited Cartier to open the response.

“We have had much success, thanks to the strong way in which John A. had held the chair.” Cartier paid the compliment easily in his high-pitched voice, the English words spoken with a heavy layer of the unique French Canadian accent.

“Now, now, George, enough of that,” Macdonald protested with a grin, his wide-set eyes squinting with pleasure.

Cartier waved, signalling to his colleague to shut up.

“John has taken us through a review, a confirmation review, of the seventy-two resolutions we agreed upon at the Quebec Conference and there have been — how shall I put it — there have been no combats!”

“Jolly good!” Carnarvon was surprised. “No fights, no amendments?”

“That’s right,” Macdonald affirmed. “No fights. One amendment to the educational clause was put forward by Alex. The clause allows religious minorities in both Upper and Lower Canada the right to appeal to the central government against any law of a provincial legislature that prejudicially affects their educational interests. Right, Alex?”

“Right. My amendment gives all provinces, including the Maritimes, the right to appeal. In that way we hope at least partly to mollify the Roman Catholic bishops who want equality for their religion in educational matters even in the Maritimes.”

“So you left that problem to be settled by each province in its own way after Confederation.”

“With a right to appeal,” Galt explained, “that I expect will never be used.”

“Also the Maritimers are insisting on a guarantee by the central government that their beloved intercolonial railway will be built,” Cartier said.

“There’s been much noise and wing about that, but nothing’s settled,” Macdonald observed.

Galt added, “And in my bailiwick, the Finance Minister’s world, several resolutions that relate to property and finance have been referred to a committee of three financial wizards …”

“Of which you are the principal wizard.” Macdonald laughed with the others.

“No bloody doubt about that, dear boy!” Galt agreed, slapping his knee in emphasis.

Carnarvon asked, “So I gather that the principles laid out in the Quebec Resolutions will stand? There’s no serious challenge to them, particularly those dealings with the specific powers of the provinces and the overriding residual powers going to the central government?”

“Exactly right, Harry,” Macdonald confirmed.

“Good. You see, gentlemen, I’m most anxious to get a proper draft of the legislation under way. It’s a laborious process, as we all know. So, if you tell me the Quebec Resolutions are going to survive relatively unscathed, I can get the drafting gnomes started immediately. We are pressed for time, are we not, John A.?”

“We most certainly are. The Nova Scotia legislature must dissolve by spring and the seventy-two resolutions of the Quebec Conference still haven’t been put to that legislature for confirmation.”

Galt added, “The Nova Scotia delegates are here and lawfully empowered to represent their government, which is fully supportive of confederation. But their spring election might well put in an anti-confederation government, and all our efforts would be for naught. So we’ve got to get on quickly with … we have to decide quickly.”

“I must also move quickly,” Carnarvon said. “Our parliament opens again on February fifth. That gives us fewer than sixty days to prepare and settle the bill so that I can introduce it in the Lords as soon as possible after the opening formalities.” He looked to Macdonald. “John A., you’ll be back in London tomorrow. I know you and Sir Frederic get on well.” Sir Frederic Rogers was the senior civil servant, the Permanent Under-Secretary in the Colonial Office. “I would be obliged if you would arrange to call upon him on Thursday and hand him a note, which I shall write, instructing him to take the appropriate steps to do another draft of the British North America bill. The first draft, the earlier one done by my people, was a disaster. You can explain the urgency.”

“Yes, I’d be happy to do that. I know he already has a copy of the Quebec Resolutions.”

“Even so, he’ll need copies for the drafting staff. Perhaps you could take along a half dozen or so — if you have them,” Carnarvon said as he passed the port again. This time all three accepted.

He asked, “So you’re still intending to include as much of the British parliamentary system as possible, having regard to your country’s enormous distance and regional differences, right?”

“And also having regard to the ethnic and language differences,” Cartier was quick to point out. “As, you know, Harry, my Quebec — Canada East, Lower Canada, whatever — is French. We come from the sixty thousand French who were there when your English army defeated us on the Plains of Abraham. We have kept our own language, religion, culture, and code of civil laws. I am satisfied that with the creation of the Province of Quebec our rights and our distinctiveness will be reasonably protected. But only the passage of time will tell if I am right.”

“You shouldn’t have any concern about the French language and rights, George,” Galt retorted. “Christ, man, what more do you want? After all, I looked after that issue during the Quebec Conference two years ago.”

“Well, you made an effort,” Cartier acknowledged. “You took a positive step but, again, only the passage of time …”

“An effort?” Galt snorted derisively. He addressed Carnarvon. “George has a memory as short as a pig’s tit, Your Lordship … Harry. It was I myself who took care of the French problem, not George. The member for Sherbrooke, Quebec — that’s I — I proposed the language resolution at the Quebec Conference!”

Carnarvon thought for an instant that he should intervene. But this situation promised to be educational and entertaining. It might provide him with a valuable insight into the minds and personalities of these colonial leaders, people who clearly displayed their lower-class origins. He puffed on his cigar, sipped on his port, and listened.

Galt leaned forward, glaring at Cartier. “Remember my resolution, George? If you’ve forgotten, let me remind you. It was carried unanimously. Even you voted for it!” Galt shouted.

Carnarvon softly suggested, “I wonder, Alex, if you might be good enough to recite the purport of your language resolution. Can you give me the thrust of what it said?”

Lowering his tone, Galt said, “I can give you the thrust and I can also tell you what the resolution didn’t say.” Eyes intense and fixed on Carnarvon, he put down his port goblet. Clenching his thick fingers together, he spoke. “My resolution was in no way a statement of the general principle that the British American federation was to be a bilingual or bicultural nation. Not at all. Canada West and the Maritime colonies are not French. Quebec is French except for the large English numbers in Montreal and around my Sherbrooke base.

“But there had to be some strong recognition of the French language by the central federal government, because it will oversee the affairs of our national interest.”

Macdonald was becoming impatient and showed it. “For God’s sake, Alex, tell Harry what your goddamn resolution was.”

“All right, all right. By faulty memory I may leave out a word or phrase but this is the way it went. I moved ‘that in the general legislature and its proceedings …’”

“By general legislature,” Carnarvon broke in, “you mean the upper, appointed federal body together with the elected House of Commons, the confederated House — as opposed to the colonial or subservient provincial legislatures. Am I right?”

“Correct. I moved that in the general legislature and in its proceedings both the English and the French languages may be equally employed. And also in the local legislature of Lower Canada and in the federal and lower courts of Lower Canada.”

Carnarvon was perplexed. “Why would you frame your resolution in such a way? It gives French a place in the federal level and obviously in Lower Canada, Quebec, but not elsewhere in the country?”

“Perhaps I can explain.” Macdonald couldn’t resist. “Alex’s motion, his resolution, recognized that a concession should be made to the French-speaking minority in our new capital city of Ottawa in exchange for a like concession to the English minority in Lower Canada.”

Carnarvon admitted, “Perhaps it’s the wine and port, but let’s see if I have it right. The proposed legal status of the French language in your asked-for national parliament will not be extended to the legislature and courts of any of the confederating provinces other than Lower Canada. Am I right?”

“That’s right, sir,” Macdonald continued. “Canada as it now stands — Canada West and Canada East — is bilingual only insofar as the debates and records of its legislature and the proceedings of the courts of Canada East are concerned. The French language had no legal standing in the courts of Canada West, nor in the courts or legislatures of any of the Maritime provinces, even in New Brunswick.”

“Even though New Brunswick has a large number of French-speaking people,” Cartier added.

“But they’re only a minority of the population.” Galt had to make that point.

“Yes, yes, of course,” Cartier agreed.

Macdonald, ever the moderator, decided it was time to move away from the highly sensitive issue of French language and culture. In any case, the conference had put the matter to bed. Rehashing it further over port and cigars in the presence of the Colonial Secretary would only increase antagonism and enmity.

“So, Harry,” he said, “while the conference is going well and the Maritime representatives seem to be getting along with us strange folk, the British in Upper Canada and the French in Lower Canada — we folk who seem to be able to live together notwithstanding our racial, cultural, religious and language differences — I must add that some unforeseen element, emotion, or event may yet appear that will destroy our purpose to unite all the British colonies in America in a single confederation.”

“John, you’re just a bag of wind who can’t resist making a speech.” Galt couldn’t avoid taking the friendly shot across Macdonald’s boozy bow. “And what he didn’t say, Harry, was the uniting all the British colonies will eventually include the North-Western Territories and those on the Pacific coast, Vancouver Island, and British Columbia.”

Macdonald grunted his agreement, saying, “Those two, Vancouver Island and British Columbia, are critically important to us. Without them, and without the North-Western Territories, our goal of a single unified nation from sea to sea will be lost.”

The Colonial Secretary’s cigar was down to a two-inch butt, having been consumed with pleasure as he listened to the three Canadians speaking, each with his own accent. In that splendid library Henry Carnarvon was hearing a hint of the multitude of languages and races that might someday be found in that land so large that an Englishman sitting on his tight, powerful little island with its empire cast all over the world like a golden net could not intellectually grasp or conceive of its enormous size. Even if he visited there, which Carnarvon (like virtually all the members of the Lords and Commons who would have to vote on the British North American legislation) had not, it would have been nigh impossible to comprehend the vastness, the kaleidoscope of the terrains of the British possessions in America.

“Well, now, the mention of Vancouver Island and British Columbia, and for that matter, the North-Western Territories, brings me to what I said earlier about Seward and the Americans.”

“We hadn’t forgotten about that,” Macdonald reassured him. “You called it a Washington rumour.”

“Indeed, that’s all it is, a rumour. But it’s a very disturbing one, particularly from the point of view of your objective, which is also mine — the creation of a unified British North America from the Atlantic to the Pacific.”

“And the Arctic,” Macdonald added. “The Arctic is a frozen wasteland, but it is land. The Hudson’s Bay Company is there and has possession of it, but the Arctic must be ours.”

“It must indeed,” Henry Herbert agreed. “The rumour comes by way of Her Majesty’s most able envoy in Washington, Sir Frederick Bruce.”

Cartier nodded. “We all know Sir Frederick. He travelled to Quebec to visit us last summer. An impressive man. Speaks French, Parisian French, without an accent!”

“Splendid. The rumour Sir Frederick has reported, if true, could have serious consequences for your confederation plans. I have to put it as bluntly as that, gentlemen.”

“For God’s sake, Harry, what are you talking about?” Galt’s voice was at an impatient near bellow.

“Well, Bruce, through his diplomatic network, has heard that the Russian ambassador to Washington has been called back to St. Petersburg to talk with the Tsar and his advisors about the purchase of Russian America by the United States. It seems that the Tsar wants to talk about selling it because Russia is in dire financial straits. That’s what Bruce has heard and I thought you people should know about it.”

Their brains muted by the evening’s long drinking session, the Canadians did not respond immediately to what they had heard. There was an extended silence as they absorbed the implications of Lord Carnarvon’s words.

Finally Macdonald brought his hands together, fingertips touching, and rolled his eyes upward in a prayer-like position of frustration, saying, “Those bastards! That Seward sonofabitch! He’s going to buy Russian America and force British Columbia and Vancouver Island to join the United States as part of his Manifest Destiny expansion.”

The colonials well understood the concept: The United States should expand to embrace all of North America. Indeed, at every opportunity it should reach out and take in the Atlantic islands on the east and whatever it could find in the Pacific.

“If Seward gets Russian America,” Cartier pronounced. “He’ll get Vancouver Island and British Columbia. I mean, my God, why would the people of those colonies stay with us, join us thousands of miles to the east, if they are not connected in any way except by a treeless plain and an impenetrable mountain range?”

“And the North-Western Territories?” Galt’s mind was reeling. “If Seward gets Russian America, he will gobble up everything west of Lake Superior. Everything!”

Cartier said what everyone else was thinking: “If Sir Frederick’s rumour is true, our plan for a British North America confederation from sea to sea could be completely derailed. British Columbia, Vancouver Island, and the North-Western Territories will fall to the United States either by persuasion or by aggression. And who’s to stop it?”

“We are!” Macdonald was emphatic. “We should offer to buy Russian America!”

Carnarvon had to say, “Who are we? The only entity that could make an offer is Her Majesty’s Britannic government. You people have no status until the British North America bill is passed.”

“No status and no money,” Galt, the guardian of the Province of Canada’s treasury, affirmed.

“However, you’re absolutely right, John A.,” the young Earl agreed. “We, all of us together, with the government as the proposed purchaser, must get into the bidding for Russian America … whether or not the rumour Bruce has heard is true.”

Carnarvon stubbed out his near-dead cigar. “And odds are it is true. We do know that about six years ago the Americans, led by one Senator Gwin, put a proposal — in the interests of businessmen and entrepreneurs in the Pacific northwest states — to the Tsar through the Russian ambassador.”

“The renowned de Stoeckl. We’ve heard about him. He was in the thick of things, the Russian fleet in American ports during the Civil War …”

“Yes, John A. The renowned de Stoeckl. It was an offer to buy out the interests of the Russian American Company and the Hudson’s Bay Company’s licence to operate in Russian American territory. That offer was rebuffed, but only after careful consideration by Tsar Nicholas, the present Tsar’s father.”

Carnarvon paused for a moment, then continued. “Now the Russian American Company is losing huge amounts of money, and the Tsar’s brother, the Grand Duke Constantine, wants to have the Company dissolved. The subsidies to the Company are draining Russia’s coffers and killing the Russian navy’s opportunity to expand the way that its Grand Admiral, Constantine, insists it should expand.”

The Earl stood and went over to pull the tasseled cord hanging from the ceiling near the tall, ornately carved French fireplace. “I’m sure a touch of cognac would not be inappropriate, gentlemen.”

A servant appeared instantly through the library door bearing a bottle of golden Courvoisier and four crystal brandy snifters on a silver tray.

As the cognac was being served, Carnarvon settled back into his chair. “You should know, gentlemen, that at this moment de Stoeckl is in St. Petersburg. He arrived there on the American ship Union Eagle out of New York. The information reported by Sir Frederick is that his meeting with the Tsar will occur within the week.”

Macdonald threw the last of his cognac back, enjoying the searing movement of the powerful liquid flowing down his throat. “Let us be profoundly realistic, Harry.” His Scottish burr had been intensified by the alcohol he had consumed. “We canna go off half cocked over a wee rumour. But what we can do — and mind, we have a duty to do for the sake of the nation we are attempting to birth — what we can do is take the rumour seriously, as if it was a proved fact. We must prepare a plan of attack.”

“Agreed!” Galt interrupted.

“And so we have no choice but to put together two schemes. Yes, two, as I see it,” Macdonald said.

“And they are?” Carnarvon encouraged him.

“The first scheme is for the purpose of driving a wedge of distrust between the Tsar and the White House, or between de Stoeckl and Seward. I don’t know what the tactics would be but that’s the strategy. If we could do that, those two would never make a deal, even though Russia and the United States are close friends.”

“And, each of them, for their own reasons, detests Great Britain,” Cartier observed.

“Your point is well taken, John A. I can get the Foreign Secretary, the Earl of Derby, and his people to devise the tactics. They’re experts at that sort of thing. Now what’s your second scheme?” Carnarvon asked.

Macdonald tipped his glass to his mouth for the last drops of cognac. He did not protest as his host refilled the delicate crystal snifter.

“My second scheme? Ah yes. Well, as I said, we should prepare an offer to buy Russian America.”

“Since the Hudson’s Bay Company has been a licensee of the Russian American Company for God knows how long,” Galt suggested, “perhaps we could get their cooperation or advice on putting an offer together and presenting it?”

Macdonald shook his head. “No, if we’re going to do anything, we’re the ones who should put together an offer. But, as you said, Harry, the offer must be made by Her Majesty’s government. The governments of the colonies can be silent partners and can agree to repay the British government over a period of time.”

“John A.’s right,” Carnarvon observed. “And whatever is done must have the Queen’s personal imprimatur.”

“Why is that?” Cartier asked.

“Because it is her equal, in royalty terms … Tsar Alexander the Second, who will make the decisions whether to cede Russian America. And so the offer must be signed by Queen Victoria. Otherwise it’s a waste of time.”

“Harry, would you be prepared to assume the leadership of this matter for us?” Macdonald put the question in his most persuasive tone.

Carnarvon did not hesitate. “Yes, of course. My first step will be to have a chat with the Foreign Secretary.” As the colonials knew, the Foreign Secretary was also the Prime Minister. “If he’s agreeable, then we’ll set up a small secret team, headed by his Permanent Under-Secretary and mine. They can work on the details and the four of us can provide policy direction. How does that sound?”

“First class,” Macdonald announced, with his colleagues nodding their agreement. “The amount of money to offer, and how it’ll be put together, will be difficult.” Galt was such a fuss-budget about his bloody finances, Macdonald thought.

“That’ll be a matter for the Prime Minister and Mr. Disraeli — and, of course, Her Imperial Majesty. I can assure you, gentlemen, that the Queen pays close attention to the affairs of the state, particularly since she lost her beloved Prince Albert.”

Henry Herbert stood, walked to the still-roaring fire, and turned his buttocks toward it. Holding his coattails aside to allow the heat to better penetrate to the skin of his lean frame, he said, “So, gentlemen, you have given me much work to do. As I said, I will write a note to Sir Frederic Rogers instructing him to work in close concert with you people in preparing a proper British North America Act based on the Quebec Resolutions. And as soon as I come down to London later in the week, I will attend upon my good friend and Prime Minster, Lord Stanley, the Earl of Derby, to enlist his support in acquiring Russian America.”

Macdonald stood, swaying slightly and intoned, “And thereby put the boots to the conniving bastard Seward and his dreams of Manifest Destiny.”

Alexander Galt applauded, clapping his hands slowly, and said “Well spoke, John A., well spoke. Now while you’re on your speechifying feet, why don’t you compose a few rapturous words to tell His Lordship about the beautiful young miss you met on Bond Street.”

“Very good, John A.!” Cartier exclaimed. “How old is she? You’re still young and virile at fifty-two. Ah, l’amour, je pense, I think it is marvellous, even if I haven’t heard your story yet. Is she really beautiful, John? Has she big breasts, wide hips?”

“Oh, for Christ’s sake, George, you lecherous old frog. Leave off!”

John A. Macdonald’s ugly face turned a shade of deeper red. He flopped back down in his chair, crossed his long legs, and waved the black half-Wellington boot of his lifted foot. “Harry, a week ago last Monday, I met this lovely young creature — on Bond Street, as Alex says. She’s tall, almost as tall as I am, and carries herself like a queen. She has a wonderful smile, brown eyes, and dark wavy hair. And I know her family. Know them very well.”

Cartier was astonished. “What a coincidence! How old is she, John A.?”

Macdonald replied. “She’s closer to thirty than she is to thirty-five.”

“What are your intentions, John A.?” Harry had lit another cigar as he stood before the fireplace. He judged that the evening was about to become longer than he anticipated. He was anxious to join his wife in bed upstairs, especially since at dinner she had given him their secret signal that her hands were lusting to have his body that night.

“My intentions? If the truth were known, I would take her to wife in an instant, if she would have me.”

“But you’ve only just met her.”

“Well, no … as I told you, I know the family. Her brother, Lieutenant Colonel Hewitt Bernard, is a member of my staff, and he and I once shared accommodation in Ottawa. When his mother, Madame Bernard and his sister, Susan Agnes, came to live with him in Ottawa, I saw a great deal of them. But at the time I had no eye for Agnes. As you may know, Harry, my dear wife passed away nine years ago, and since then I’ve been alone with my politics, my law practice — but without the comfort and care and love of a woman. I’ve also been alone with too much drink. But that’s changed. Since meeting Agnes, except for a tiddly moment of falling off the postillion tonight in the presence of my dear colleagues and a noble host, except for that, I have been the model of behaviour.”

“Indeed,” Galt agreed. “Your performance as a chairman of this London Conference …”

“You highly intelligent, perceptive colonials appointed me chairman unanimously!” Macdonald snorted.

“Yes, well, mark that down as an error. Anyway, your performance has been devoid of any blemish of drink — and the results have been spectacular. You’ve handled the sessions and all the sensitive personalities around the table with remarkable patience and leadership.”

“Alex, leave off all this bullshit!” George shouted. “I want to hear more about Agnes. John, you’d probably like to bed her, but what are the chances that an out-of-practice fifty-two-year-old like you could do such a thing in this highly moral, painfully Puritan age without marrying her?”

“And that, my dear George, is exactly my intent, to marry her if she will have me. That’s the rub. What if she refuses me? I’ve been with her three times since we met on Bond Street, always at dinner and always with her mother or brother or both in attendance. They watched me as if I were an ancient hawk circling to steal their most precious chick.”

“Who can blame them?” Galt roared, again slapping his knee with delight.

“Who can indeed?” John A. could only agree. “Well, chaps, I shall soon put the question. Thursday, to be exact. Agnes is dining with me. Not her brother, not her mother. Just Agnes alone. I’ll do it then. I’ll work up my courage and propose!”

The fatherly Cartier cautioned, “Just don’t work up your courage with drink, John.”

Macdonald allowed, “That would be the quickest way to lose my wonderful Agnes. I have enough handicaps as it is, God knows.”

“And George and I are two of them.” Galt laughed as he stood up saying to Carnarvon, “Well, sir, it’s been a long day.”

“But a productive one,” Lord Carnarvon told him, “and there are still more matters we haven’t covered this evening.”

Macdonald struggled to his feet. “Perhaps we can address them in the morning after breakfast?”

“Yes, of course. I’m anxious to talk with you in your capacity as Canada’s Minister of Militia Affairs about that military threat from the United States in general and the Fenians in particular.”

John A. straightened his long frame. “I bid you goodnight, Harry, and thank you for your gracious hospitality.” He held back a belch. “I shall be happy to give you an appraisal of the American threat, which continues unabated, and of those Irish madmen.”