Читать книгу Sir John A.'s Crusade and Seward's Magnificent Folly - Richard Rohmer - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

4

ОглавлениеDecember 12, 1866

London

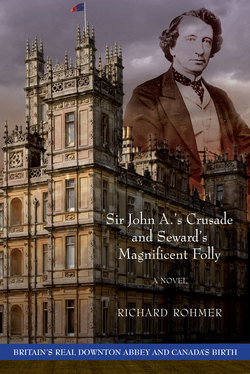

Ever the consummate host, the Earl of Carnarvon had insisted on driving with his honoured colonial guests to the sparkling new railway station at Newbury. It would have been impossible for Henry Herbert to simply see his guests off from the front entrance of Highclere Castle.

So it was that on the morning of December 12 he escorted his three visitors to board the waiting train amid the whistling vapour clouds and pulsing puffing noises of the powerful steam engine as it vibrated with energy waiting to be unleashed like a racehorse to get on to the next stop.

Carnarvon had said farewell to Galt and Cartier, adding that he would see them in London on the weekend or by Monday at the latest, and admonishing the two ministers to ensure that the work of the confederation conference went smoothly.

Then he turned to Macdonald. “Now, John A., be a good chap and take care.” He frowned as he spoke in a low, not-to-be overheard voice. “Keep a watch out for the Irish, those abominable Fenians who want us out of Ireland. They’ve been infiltrating London, setting off bombs again, terrorizing the city.” Carnarvon’s face showed his concern. “Scotland Yard is doing its best, but the Fenians are killing prominent British citizens when they think it will assist the cause of independence.”

Carnarvon hesitated. “What I’m saying is that you should be very careful about your personal safety. You could well be a Fenian target.”

“In London?” Macdonald was incredulous, and the arching of his eyebrows showed it. “That can’t be! I mean, we’re thousands of miles away from the American Fenians. Surely they won’t attack us here in England.”

“And why not? Your presence here is well known. If the Fenians of Ireland — they’re in league with the lot in America — if they come after you and did you in, it would be a great victory that might well destroy the plans for Confederation, right? Let’s face it, John A., without you the plans would collapse.”

The call to board the train was ringing in their ears. Cartier and Galt were already settled facing each other in the first-class compartment.

“I understand what you’re saying, Harry, and I will keep an eye out for anything suspicious.”

“Good. If there is anything, any problem, get in touch with Scotland Yard straightaway. And, John A., that’s wonderful news about Agnes.”

Macdonald climbed into the carriage and he pulled the door shut behind him. He then turned, lowered the door window, put on his grey stovepipe hat, and stuck his arm out the opening. Grasping Carnarvon’s hand as the first whistle signalled movement of the train, he shouted, “Thank you for that, Harry, and wish me luck!”

“You have it!”

From the time Carnarvon assumed the office of Colonial Secretary during the summer of 1866, Macdonald had been in constant communication with the new minister about the plans for Confederation and the Fenian raids. The two men were able to exchange messages rapidly by means of the magical transatlantic cable that had just been laid and put into operation.

Macdonald also reported his concerns about the enormous Grand Army of the United States, almost a million men still in uniform after the end of the Civil War six months earlier. There had been a gnawing fear in the British American colonies that as soon as the Union armies had defeated the Southern Confederacy — of which Britain had been steadfastly supportive — the entire fury and force of the victorious troops would be turned north to wreak vengeance on the British. Such an assault and conquest would be consistent with the ideas of the powerful William Seward, Lincoln’s and then Johnson’s Secretary of State who made no secret of his belief in the Manifest Destiny of the United States.

As for the Fenians, there was a strong possibility that any attack they might make across the border into British America would be the spark to ignite a serious confrontation between Britain and the United States, which could easily escalate into another war.

The Fenian Brotherhood united all its Irish American members into a strong emotional force with one intent: to free Ireland from British “subjugation.” To further that cause, the leaders of one militant branch of the American Fenian movement, filled as it was with veterans of the Civil War, had decided to go to war against the British in North America.

The Fenian movement — the main political manifestation of the Roman Catholic Irish who had flooded into America since the 1840s — was motivated not only by the traditional anti-British emotions of true sons of Ireland but also by the belief in the Manifest Destiny of their new-found nation, which they could assist by conquering British America. Thus the Fenians began assembling in Buffalo and Detroit in 1866. With much public show they started to parade and train, sure the word of their presence and intended attack would seep across the border and put the fear of God into the British colonials.

Rumours abounded in Canada that the Fenians would strike on that most symbolic of Irish occasions, St. Patrick’s Day, March 17. Macdonald’s intelligence network was certain that an assault across the Detroit and Niagara rivers would occur on that day.

It did not. The attack came many weeks later, on the night of May 31, when Colonel John O’Neill led a force of fifteen hundred Fenians across the Niagara River north of Buffalo. On the morning of Saturday, June 2, near Ridgeway, O’Neill’s “army” was confronted by a column of eight hundred and fifty Canadian militiamen. In the ensuing battle nine Canadian and many Fenians were killed, scores injured. On Sunday, learning of new British forces soon to arrive, O’Neill withdrew his men back into the United States.

That Fenian assault, combined with two other incursions and rumours of more to come that summer, convinced the British American colonies of the urgent need to seek military assistance from the United Kingdom. Finally, on August 27, on the advice of Macdonald and Sir John Michael, the General Officer commanding the regular Imperial forces in Canada, the Governor General, Lord Monck, sent off an urgent cable to Carnarvon appealing for immediate reinforcements. It was a request that was not answered by the sending of more troops.

The Fenian raids also solidified the intent of Canadians and Maritimers to combine their colonies into one nation loyal to the British Crown, safe from the threat of Seward’s Manifest Destiny.

The trip from Newbury to Paddington Station took much longer than scheduled because a thick you-could-cut-it-with-a-knife fog had settled on London, reaching as far west as Slough. The train finally entered the cavernous station at nine thirty that evening, three and a half hours late. It took an additional hour and a half to cover the short distance from Paddington to the Westminster Palace Hotel, as the cab driver and his lively young horse cautiously picked their way through the classic, thick, dark London fog.

It was well past eleven o’clock when the three weary travellers entered into the anteroom that led to their separate rooms on their second-floor suite, their bags hefted in behind them by the night porter and his assistant.

Macdonald, exhausted, bade his companions goodnight, but not before saying to them, “I must have said this a dozen times today. I’m really worried about the sale of Russian America to the Yankees. I’d like to brief the conference on the situation as soon as possible. Alex, when can you have ready a rough draft of the financial terms really?”

“First, I have to know how much we are … the British are prepared to offer, if anything.”

“The main number?”

“How much are you prepared to offer?”

Macdonald’s brow furrowed. “Use ten million dollars U.S. as your calculating base. If a higher or a lower figure is decided on, it’ll be easy to recalculate. I’ll talk to Carnarvon when he gets back to London. He can open the Prime Minister’s door for me as well as the Chancellor of the Exchequer’s.”

“Next Monday, the seventeenth,” Galt said. “I’ll need until then. Eight thirty, here in our anteroom. I’ll get breakfast organized. All right, George?”

Macdonald smiled. “Have a good sleep, chaps.”

Moving with hesitant care in the darkness, Macdonald entered his bedroom, the dim wavering light from the hall candles giving his tired, searching eyes nearly no aid in finding his way across the carpet to the foot of the bed. But once he reached it his hand groped along the soft edge of the eiderdown until his fingers felt the table as the bedside, then the candle that would bring the room alive with its flickering flame. He fumbled for a match from his waistcoat pocket. There it was, its slim wooden shaft moving warmly between his thumb and forefinger, which were far more used to holding a glass.

He shoved the head of the match down to the rough underside of the tabletop and moved it swiftly across the coarse surface, his favourite place for match-striking in the comfortable high-ceilinged corner room. The first attempt was unsuccessful but the second brought a spark of light as the sulfur started to burn. Then, with a billowing burst of yellow-white flame and a rush of sound from its minuscule explosion, Macdonald’s match was alight.

His shaking hands — that shaking had just recently started, nothing severe and only in spurts — held the match to the candle’s waxed white cord until the shaft of blue-tipped light was transferred completely to it. As the candlelight spread, Macdonald stood for a moment, his eyes transfixed by the dancing fire. Then he blew out the match flame as it nearly reached his fingers. Looking around the room, he saw with pleasure the pile of newspapers on the bed, the Times on top. Good. The concierge, as he had been asked to do, had delivered all the day’s papers so that Macdonald would have them to read upon his return from Newbury. Newspapers were the most important documents — that’s what he called them — in Macdonald’s life. From their pages he absorbed information, facts, and opinions the way a sponge soaks up liquid. Newspapers were the stuff that John A. Macdonald, by his own account a workaday politician, thrived on.

It was time to get into bed and read those beckoning journals. He went to the water closet down the hall, then back to his room, shutting but, as was his custom, not locking the bedroom door. After all, this was London, the most civilized city in the world and the most crime-free. Carnarvon’s words of caution had already been forgotten.

Macdonald undressed, put on his flannel nightshirt, left his socks on to keep his feet warm, and, climbing into bed, grunted with satisfaction as the bedclothes enveloped his long, tired body. He reached for the Times while slipping his spectacles onto the bridge of his slightly bulbous nose.

Laying back, his large head on two pillows, he held the Times in both hands, scanning the headlines of the front page. There was, of course, no news from British North America. There never was anything about the colonies in the London papers. It was as if they didn’t exist. But as to what was going on in the United States and Europe, that was a horse of a different colour.

Macdonald was keen to obtain information out of Washington: what was the Congress up to? What was the incompetent president, Andrew Johnson, doing or thinking, especially about the U.S. relations with the British colonies to the north? And Secretary Seward, the Manifest Destiny man, what news of him, all the more important now if the Russian ambassador to Washington was in fact in St. Petersburg to get instructions from the Tsar about selling Russian America to the United States?

Macdonald, eyelids drooping, started to read the column headlined “Impeachment of U.S. President Possible.” As he read he turned for comfort onto his left side, folding the newspaper to better focus on the Johnson column. His mind, slipping fast into sleep, told him he had to blow out the candle just inches from his face. Then John A. Macdonald was sound asleep.

It was the searing heat against his right shoulder that wakened him. He couldn’t be sure what was happening. There was fire all around him. The newspaper, the bedding, the curtains over the window, were ablaze; vicious yellow-orange flames crackled and roared as the fire consumed them, spewing acrid black smoke that was billowing and filling the room.

In the split second that it took to assess the danger, Macdonald knew what he had to do if he was to survive the growing inferno. He thrashed his way out of bed, throwing off the flaming newspaper, doubling the eiderdown over on itself to smother the flames that were ravaging it. As his feet hit the floor he reached for the far part of the window covering not yet burning and hauled on it with all his considerable weight. The whole curtain, its rod and centre core in flames, came crashing down. Macdonald grabbed for the huge water jug on the washstand and poured its full contents onto the curtain’s still blazing remnants, extinguishing its fire immediately.

Turning to the bed, he threw the burning eiderdown to the floor, ripping it and pillows open. He later described the scene to Susan Agnes Bernard as pouring “an avalanche of feathers on the blazing mass.” The feathers were enough to cut off the oxygen feeding the fire and the flames disappeared.

But Macdonald needed more water to finish the job. He hurried through the common sitting room he shared with Cartier and Galt and banged on their doors, not loudly because he did not want to create an alarm throughout the crowded hotel. A shout of “fire” would have caused pandemonium. Macdonald knew he had the fire under control, but he wanted his colleagues’ help and their water jugs to extinguish it completely.

Opening Cartier’s door after knocking on it, he said in a calm voice, “George, are you awake? I need your help. I’ve had a fire.”

He could hear the bed squeak as Cartier sat up. “A fire? Mon Dieu!”

“Bring your water jug right away, and your candle so we can see what we’re doing.” Macdonald went to Galt’s door, repeated the process, then hurried back to his smoke-filled room. Cartier and Galt were on his heels, lugging their heavy water containers and their lighted candles.

“Here, let me do it,” Macdonald said, taking Cartier’s jug, pouring its precious contents on the smouldering portions of the eiderdown. “How does the curtain look, Alex? Will you check it out?”

Galt, jug at the ready, went to the blackened, sodden heap that had been the curtain. “Looks as though you got it all, John A.”

“Good. And I think I’ve finished this one off. Would you mind opening the window, please, George? Better shut the door first. Just put your water jug over there on the floor in case I need it.”

Macdonald was pouring the last of Cartier’s water when Galt came up to him saying, “Your shoulder — you’ve been burned, John. Christ, it went through your nightshirt. Let me take a look.”

“Be careful, Alex. It hurts like hell.”

“It looks like hell,” Galt said as he gingerly lifted the charred edges of the near circular eight-inch hole in the right shoulder of Macdonald’s nightshirt. “It’s blistering already. We’d better get a doctor. I think there’s one staying in the hotel.”

“No, I’ll be all right. Really. The main thing is to get this mess cleaned up. If you’d fetch the night porter, he’ll do it.”

“And we’ll get him to bring some sheets and pillows and a new eiderdown. What happened, John?”

Macdonald shook his head. “I don’t know. I’m sure I blew out the candle before I dozed off. I’m sure I did.”

“But obviously you didn’t,” Cartier said. “You must have fallen asleep with the candle burning. The newspaper you were reading probably fell on your night table …”

“Next to the candle,” Galt added, “and away it went.”

“But I blew it out,” Macdonald insisted. “I blew that goddamn candle out! I know I did.”

“Sure, John A., sure. I’ll get the night porter.” Galt went to the tasselled call cord by the door, pulled it twice, and turned toward Macdonald. “I’m going to get a doctor, John A., whether you like it or not.”

Macdonald muttered as he wearily lowered himself into the bedroom’s sole stuffed-leather armchair. “You’re probably right.”

“Y’know, we can’t have you incapacitated. You’re doing such a marvellous job as chairman of our conference, putting out all the fires, so to speak.”

Macdonald laughed, then grimaced. “God, Alex, I’m having enough pain from my shoulder, let alone your humour.”

“Ah, well, I’m only trying to make light of the matter. Where’s that bloody night porter? Probably asleep.”

As Galt spoke there was a knock on the door. “Come in!” he roared.

The night porter opened the door, his eyes widening as he took in the charred remains and the stench of the fire.

“Cor, luv a duck. Wot’s ’appened ’ere, sirs?”

“Just an accident, Ben,” Macdonald replied. “Just an accident. I’ll deal with the manager about the damages. I’ll see Mr. Gates in the morning.”

“Right, sir. Sorry I was so long in comin’, but me night assistant he jus’ up an’ quit not more than ten minutes ago and, well, like I ’ad to look after an earlier call.”

“It’s alright, Ben. Can you clear this up for me and bring me sheets and pillows and an eiderdown for the bed?”

“Certainly, Mr. Macdonald. Right away, sir. If my assistant hadn’t quit … those bloody Irishmen. You can never tell what they’re going to do next. Kelly’d only started with us day before yesterday and he up and quits in the middle of the bleedin’ night.”

“Kelly? Obviously an Irishman.”

“As Irish as Paddy’s pig.”

“Who hired him?” Macdonald’s mind was locking onto Carnarvon’s cautionary word about the Fenians, words he had dismissed with a wave of the hand.

“I did, sir. He seemed a likely lad. Anxious to work. Full of the Irish blarney and all. Knew there was a lot of Canadians staying in the ’otel. Said he has relatives in Canada and the U.S. Had experience in other London ’otels, the Strand an’ such. Bright lad, sir. Good worker. We got on well. No idea why he’d quit.”

“Where is he now?”

“I don’t know, Mr. Macdonald. All I know is he couldn’t get out of ’ere quick enough. Only about ten minutes ago or so. Got out of his uniform, put on his civvy clothes, said ‘We’ll get all you British bastards out of Ireland yet,’ and he was gone. Didn’t even ask for his pay!”

Macdonald grunted. “His pay was the privilege of putting the torch to this room, the honour of killing me as I slept, a Fenian killing me for the honour of Ireland. And he almost succeeded.”

“You mean Kelly started this bloody fire?” Ben’s mouth was agape with astonishment. He couldn’t believe his ears. Nor could Cartier and Galt, both of whom were uncharacteristically speechless.

Macdonald struggled to his feet, his hand clutching his right arm just below the area of his burn. He was in deep pain, his face twisted by it as he stood.

He looked intently at his colleagues and the night porter. “Not a word about how this fire started, gentlemen. Not a goddamn word. But there’ll have to be an explanation about the fire and the burn.”

“Of course, John A.” Cartier understood immediately. “If this man Kelly was a Fenian …”

“He was, make no mistake about it. Carnarvon warned me about them when we were getting on the train at Newbury.”

“But you didn’t tell us,” Galt protested.

“Of course not. I didn’t think anything of it. No need to get you two alarmed, that’s what I thought. And I was wrong.”

“Almost dead wrong. I’ll go and fetch the doctor.”

“Good. And remember, this was an accident. I fell asleep, didn’t get the candle blown out. The newspaper caught fire. You hear that, Ben?”

“Yes, sir, Mr. Macdonald. I hear you strong, I do. I’ll clean all this up straightaway, sir. Cor, wot a bloody mess.”