Читать книгу Enemies Within: Communists, the Cambridge Spies and the Making of Modern Britain - Richard Davenport-Hines - Страница 29

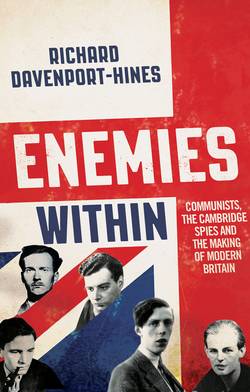

Norman Ewer of the Daily Herald

ОглавлениеNorman Ewer had been born in 1885 in the middling London suburb of Hornsey. His father dealt in silk, and later moved to Muswell Hill. The family kept one live-in housemaid. Ewer rose up the rungs of the middle class by passing examinations. He attended Merchant Taylor’s School in Charterhouse Square in the City of London, and Trinity College, Cambridge, where he won first-class degrees in mathematics and history. From an early age, he was nicknamed ‘Trilby’ because, like the heroine of George du Maurier’s novel, he liked to be barefoot. After Cambridge he became private secretary to an exotic plutocrat known as Baron de Forest.

Born in 1879, de Forest was ostensibly the son of American circus performers who died of typhoid when their troupe visited Turkey. After a spell in an orphanage, he was adopted in 1887 by the fabulously rich Baroness Hirsch, who believed that he was the illegitimate child of her dead son. He inherited a castle and many millions in 1899, was created Baron de Forest by the Austrian Emperor and converted from Judaism to Catholicism. Subsequently he settled in England, where he held the land-speed record and was the victorious radical candidate at a parliamentary by-election in 1911. He forthwith spoiled his political prospects by suing his mother-in-law for slander. In 1912 de Forest contributed to the fund launched by the Labour MP George Lansbury to save the fiercely partisan Daily Herald from insolvency. Ewer was installed as de Forest’s nominee in the Daily Herald management: he soon became, together with the young Oxford graduates G. D. H. Cole, Gerald Gould and Harold Laski, one of ‘Lansbury’s lambs’ working as a journalist there. His idealism became the overworked centre of his existence.

After the outbreak of war in 1914 Ewer opposed conscription, registered as a conscientious objector, became an indentured agricultural worker in Waldorf Astor’s pigsties at Cliveden and published anti-war verses. He was aghast at the mayhem of the Western Front, was revolted by the militarism of the Austrian, British, German and Russian monarchies, and loathed the inequities of free-market capitalism. He saw the undoubtable humbug of the British claim to be fighting for liberal democracy when its main ally was tsarist Russia, which had sponsored the pogroms of 1903–6 and sent dissidents into captivity and internal exile. As Ewer wrote in 1924, Lenin emerged as the greatest historical leader of the epoch because he saw world revolution, not national victory in the European war, as the primary aim. German socialists collaborated with German capitalism, British socialists exerted themselves for national interests, and pacifists strove for peace. ‘Only the great voice of Lenin cried from Switzerland that all were wrong; that the job of Socialists was Socialism; neither to prosecute the Imperialist war nor to stop the Imperialist war, but to snatch a Socialist victory from the conflicts of Imperialism; to turn war into revolution.’ For Ewer, like Lenin, imperialism was the apotheosis of capitalism.6

When Ewer applied for a post-war passport to visit the Netherlands and Switzerland, Gerald Gould assured the Foreign Office that the ‘extreme’ socialism preached in the Daily Herald was a bulwark against Bolshevism. Counter-espionage officers assessed him differently. ‘EWER is pro-German principally on the grounds that other Governments are not less wicked than the German,’ reported Special Branch’s Hugh Miller. ‘He preaches peace with Germany, followed by “revolution through bloodshed”.’ In Miller’s estimate, Ewer was a risk to national security: not only ‘a clever writer and fluent speaker’ but ‘a dangerous and inflammatory agitator’.7

In 1919 Ewer was appointed foreign editor of the Daily Herald. He collaborated during that year with the pro-Bolshevik MP Cecil L’Estrange Malone and a director of the Daily Herald named Francis Meynell in formulating a programme for a Sailors’, Soldiers’ & Airmen’s Union which would certainly have been revolutionary in intent. Ewer became a founding member of the CPGB in 1920, and liaised between the newspaper, CPGB headquarters in King Street and Nikolai Klyshko, who was both secretary of the Soviet delegation that arrived in London in May 1920 to negotiate a trade agreement and the Cheka chief in London. Klyshko controlled Soviet espionage in Britain, and funded subversion, until his recall from London in 1923.

George Lansbury visited Moscow and met Lenin in 1920. ‘I shall always esteem it the greatest event in my life that I was privileged to see this fine, simple, wise man’, he wrote in besotted terms in his memoirs. Lenin was ‘a great man in every sense of the word’, who held supreme national power and yet remained ‘unaffected and without personal pride’. Lansbury, who became chairman of the Labour party in 1927 and its leader in 1932, told the party conference at Birmingham in 1928 that the Bolshevik revolution had been ‘the greatest and best thing that has ever happened in the history of the world’. Socialists should rejoice that the ‘fearful autocracy’, which ruled from the Baltic to the Black Sea and from the Volga to the Pacific, had been replaced by that magnificent venture in state socialism, the Soviet Union. ‘The peasants and workers of that great nation, encircled by implacable foes who ceaselessly intrigue, conspire and work to restore Czardom, need our sympathy and help, and we need theirs.’ It was the role of the Daily Herald, thought Lansbury and his lambs, to provide and receive sympathetic help.8

In August 1920 GC&CS intercepted and deciphered a signal from Lev Kamenev, the Bolshevik revolutionary leader and acting head of the Soviet trade delegation, reporting that he had given to the Daily Herald a subsidy of £40,000 raised by selling precious stones. In return, it was understood that the newspaper would be the mouthpiece of Moscow on Anglo-Russian relations and would support Bolshevik agitation and propaganda against the Lloyd George government. Meynell, the courier used to smuggle many of these jewels, made several visits to Copenhagen to meet Moscow’s star diplomat Maxim Litvinov. The surveillance of these meetings was comically blatant: a window-cleaner appeared on a ladder, and a banister-polisher on the landing, whenever Meynell entered Litvinov’s hotel suite. Once Meynell returned from Copenhagen with two strings of pearls secreted in a jar of butter. On another occasion he posted a box of chocolate creams, each containing a pearl or diamond, to his friend the philosopher Cyril Joad. All these shenanigans were known to Ewer, although it may have been kept from him that £10,000 of the jewels money was invested in the Anglo-Russian Three Ply and Veneer Company run by George Lansbury’s sons Edgar and William. Edgar Lansbury was a member of the CPGB, who in 1924 was elected communist mayor of Poplar. His mother-in-law, Hannah (‘Annie’) Glassman, was used to convert the jewels into cash.9

MI5 resorted to family connections and social contacts in order to handle Kamenev and the Daily Herald. Jasper Harker had recently married Margaret Russell Cooke at a Mayfair church. She was the sister of Sidney (‘Cookie’) Russell Cooke, an intellectual stockbroker and Liberal parliamentary candidate, who had inherited a fine house on the Isle of Wight called Bellecroft. Russell Cooke had been a lover of Maynard Keynes, whose lifelong friend and business associate he remained, and was the son-in-law of the captain of the Titanic. Virginia Woolf called him ‘a shoving young man, who wants to be smart, cultivated, go-ahead & all the rest of it’. Harker used his brother-in-law to compromise Kamenev. Russell Cooke invited Kamenev and the latter’s London girlfriend Clare Sheridan, who was a sculptor, Winston Churchill’s cousin and a ‘parlour bolshevik’, first to lunch at Claridge’s and then to stay at Bellecroft for an August weekend. Lounging on rugs by the tennis court, Kamenev spoke vividly for over an hour, ‘stumbling along in his bad French’, about the inner history of the revolution in 1917, recounting the ‘secret organizations’ of Lenin, Trotsky, Krasin and himself, and depicting the Cheka’s chief Felix Dzerzhinsky: ‘a man turned to stone through years of travaux forcés, an ascetic and fanatic, whom the Soviet selected as head of La Terreur’. Kamenev inscribed a poem in which he likened Sheridan to Venus on a £5 banknote. He signed Bellecroft’s visitors’ book with the slogan, ‘Workers of the World Unit [sic].’10

Next month, on the eve of Kamenev’s scheduled return to Moscow with Sheridan, Lloyd George upbraided him for his part in the contraband-jewels subsidy. In order to gain political advantage, Lloyd George’s entourage spread the notion that he had given Kamenev peremptory orders to leave the country. The Prime Minister also yielded to pressure to publish the intercepts in order to justify his confrontation with Kamenev, although this compromised future SIGINT by betraying the fact that GC&CS could read Moscow’s ciphered wireless traffic. Journalists duly raised uproar about the Daily Herald diamonds under such headlines as ‘Lenin’s “Jewel Box” a War Chest’.11

When Kamenev and Sheridan left together for Moscow, Russell Cooke found an excuse to meet them at King’s Cross station, to accompany them on their train and to see them on to their ship. Sheridan’s handbag went missing on the journey, and was doubtless searched. At Newcastle it reappeared in the clutches of Russell Cooke, who claimed to have traced it to the lost luggage office. In Moscow Sheridan sculpted heads of Lenin, Dzerzhinsky, Trotsky, Zinoviev and other Bolshevik leaders. Soon afterwards, the Cheka informed Kamenev that Sheridan had lured him into staying with the brother-in-law and informant of an MI5 officer, and she found herself shunned when she returned to Moscow in 1923.12

Meanwhile, on 28 February 1921 the Daily Herald published a photograph of an imitation of the Bolshevik newspaper Pravda which was circulating in England. The identifying marks of printers in Luton proved this issue to be a forgery which, as the Home Secretary admitted in the Commons, had been prepared with the help of the Home Office’s Director of Intelligence, Sir Basil Thomson. This trickery was adduced by Ewer, when MI5 interviewed him in 1950, as his reason for starting his counter-intelligence operation. In fact the groundwork had been laid before the forged Pravda incident; but it is true that his network coalesced in 1921.13

Hayes was the talent-spotter who put Ewer in touch with dismissed NUPPO activists and disaffected Special Branch officers willing to undertake political inquiries. Ewer in turn exerted his jaunty charm to inspire his operatives with team spirit. They wanted to prove that they could do a good job for him, both individually and as a group. Their skills were a source of pride to them. Shadowing and watching in the streets of London was akin to a sport that needed brains as well as agility. Smarting from their dismissals by the Metropolitan Police, they were glad to join an organization that appreciated team-work. The Vigilance brigade of detectives believed in manly self-respect and masculine prowess.

Ewer’s security officer Arthur Lakey had been born at Chatham in 1885. His father came from Tresco in the Scilly Isles: his mother was an office cleaner and munitions worker from Deptford. He worked as a railway booking clerk and in a brewery office before enlisting in the Royal Navy in 1900 and serving on the torpedo training vessel HMS Vernon. He left the navy to join the Metropolitan Police in 1911, but was recalled for war service, and spent eight hours in the sea when his ship was torpedoed in 1916. After this ordeal, he kept to land and was employed as a sergeant in Special Branch. During the NUPPO struggles of 1918–19, Lakey entered General Macready’s office at Scotland Yard, rifled his desk, read confidential papers and reported their contents to NUPPO.

In 1921, while Lakey was in the Doncaster mining district raising relief funds for dismissed NUPPO activists, he was summoned by Hayes to meet Ewer in the Daily Herald offices. Ewer asked him to investigate the circumstances of the Pravda forgery, implying that the inquiry was on behalf of the Labour party. When Lakey tendered his report, Ewer told him that the work had been commissioned on behalf of the Russian government and established that he had no misgivings about undertaking further work for the same employer. He was put in contact with Nikolai Klyshko, who paid the rent of a flat at 55 Ridgmount Gardens, Bloomsbury, where Lakey lived and worked to Klyshko’s orders. Walter Dale and a policeman’s daughter named Rose Edwardes worked with Lakey in Ridgmount Gardens.

Hayes also introduced Ewer to Hubert van Ginhoven and Charles Jane, who held the ranks of inspector and sergeant in Special Branch, and were discreet NUPPO sympathizers. Ewer began paying them £20 a week to report on Special Branch registry cards on suspects, on names and addresses subject to Home Office mail intercept warrants, and on names on watch lists at major ports. They also furnished addresses of intelligence officers and personnel, and gave forewarnings of Special Branch operations. In addition Ginhoven and Jane supplied material enabling Ewer to deduce that communist organizations in foreign capitals were under SIS surveillance, which made it easier to identify SIS officers or agents abroad who were targeting these foreign organizations. Leaks were facilitated by the Special Branch practice of trusting officers with delicate political information. This guileless, unreflecting camaraderie had nothing to do with the old-school-tie outlook or class allegiances (Guy Liddell and Hugh Miller were rare within Special Branch in being privately educated). It was how men at work were expected to behave with one another.

Ginhoven, who worked under the alias of Fletcher within the Ewer–Hayes network, was a familiar visitor to the Special Branch registry, where he flirted with women clerks and snooped when they had gone home. Every week or ten days Ewer dictated an updated list supplied by Ginhoven of addresses for which Home Office warrants had been issued. These were typed in triplicate, with one copy going to Chesham House (the Soviet legation in Belgravia), another to Moscow via Chesham House and the third to the CPGB. It was found in 1929 that traces of Home Office warrants issued for Ewer’s associates, together with any intercepted letters, had vanished from the files at Scotland Yard. So, too, had compromising documents which had been seized during the police raid on CPGB headquarters in 1925.

The Vigilance detectives resembled tugs in the London docks, sturdy and work-worn, speeding hither and thither, but taken for granted and therefore unseen. The material collected by them served as tuition lessons for Soviet Russia in British tradecraft. By watching targeted individuals, Vigilance operatives identified SIS and MI5 headquarters. They shadowed employees from these offices to establish their home addresses. They tracked messengers, secretarial staff and official cars. In 1924 they realized that Kell was MI5’s chief by tracking him from his house at 67 Evelyn Gardens: surveillance was easy, because his address was in Who’s Who and the Post Office London Directory, and his chauffeur-driven car flew a distinctive blue pennant displaying the image of a tortoise with the motto ‘safe but sure’. They watched MI5 and Special Branch methods of monitoring Soviet and CPGB operations, and thus helped the Russians to study and improve the rules of the game. They checked that Ewer and his associates were not being shadowed by the British secret services. They observed embassies and legations in London, and tracked foreign diplomats. Possibly this surveillance led to the recruitment of informants, although no evidence survives of this. Vigilance men monitored employees of ARCOS, CPGB members and Russians living in England who were suspect in Moscow eyes. ‘If a Russian was caught out, invariably he was sent home and shot,’ boasted Ewer’s chief watcher in 1928.14

Ewer, under the codename HERMAN, was Moscow’s main source in London. He accompanied Nikolai Klyshko to Cheka headquarters in Moscow in 1922, and visited Józef Krasny, Russian rezident in Vienna. He returned to Moscow in 1923 in the company of Andrew Rothstein @ C. M. Roebuck, a fellow founder of the CPGB and London correspondent of the Soviet news agency ROSTA. He also became the lover of Rose Cohen. Born in Poland in 1894, the child of garment-makers, Cohen had been reared in extreme poverty in east London slums. After studying politics and economics, she joined the Labour Research Department, and was a founder member of the CPGB. Harry Pollitt, who became general secretary of the CPGB in 1929, was among the men who became infatuated with this ardent, clever and alluring beauty, whom Ivy Litvinov described as ‘a sort of jüdische rose’. Cohen criss-crossed Europe after 1922 as a London-based Comintern courier and money mule. Eventually she committed herself to a monstrously ugly charmer, Max Petrovsky @ David Lipetz @ Max Goldfarb, a Ukrainian who translated Lenin’s works into Yiddish and went to England, using the alias of Bennett, as Comintern’s liaison with the CPGB. Together Cohen and Petrovsky moved in 1927 to Moscow, where her manners were thought grandiose by other communist expatriates.15

Ewer returned from Moscow in 1923 with boosted self-esteem and instructions, or the implanted idea, to run his espionage activities under the cover of a news agency. Until then, it had been based in Lakey’s Bloomsbury flat, or later in premises at Leigh-on-Sea: Ewer had met Lakey and other operatives either in cafés or at the Daily Herald offices. Accordingly, in 1923, Ewer leased room 50 in an office building called Outer Temple at 222 The Strand, opposite the Royal Courts of Justice at the west end of Fleet Street. There he opened the London branch of the Federated Press Agency of America, a news service which had been founded in 1919 to report strikes, trade unionism, workers’ militancy and radical activism. The FPA issued twice-weekly bulletins of news, comment and data to its left-wing subscribers. It was based first in Chicago, shifted its offices to Detroit and then Washington, before settling in New York. The FPA had developed reciprocal relations with socialist, communist and trade union newspapers internationally and acted as an information clearing-house in the United States and Europe. It may have served broad Comintern interests, but was not a front organization for Moscow. According to Ewer, the only American in the FPA who knew that its London office operated as a cover for Russian spying was its managing editor, Carl Haessler, a pre-war Rhodes scholar at Oxford.

Moscow sometimes sent money to Haessler in New York, who remitted funds either to the communist bookshop-owner Eva Reckitt in London or to the Paris correspondent of the Daily Herald, George Slocombe. Usually dollars arrived in the diplomatic bag at Chesham House and were distributed to the FPA and the CPGB by Khristian Rakovsky, Soviet plenipotentiary in London from 1923 and Ambassador from 1925. An associate of Ewer’s named Walter Holmes (sometime Moscow correspondent of the Daily Herald) converted the dollars into sterling by exchanging small amounts at travel agencies and currency bureaux. These arrangements ended after the ARCOS raid in 1927.

For a time Ewer had a source in Indian Political Intelligence (IPI), who was dropped because the product was suspected of being phoney. Ewer had a sub-source in the Foreign Office, who reported confidential remarks made by two officials, Sir Arthur Willert of the Press Department and J. D. Gregory of the Northern Department; but his network never obtained original FO documents which could be sent to Moscow for verification. Probably the remitted material from the Foreign Office and India Office was limited to low-grade gossip. Don Gregory, the Office’s in-house Russian expert until 1928, enjoyed his half-hour briefings with Ewer, whose facetious anti-semitism amused him: ‘he is an admirable and loyal friend, though I have heard him described as a dangerous bolshevik’. The only diplomatic documents obtained by Ewer’s network came from his second prong in Paris, where his sub-agent was the Daily Herald correspondent George Slocombe.16