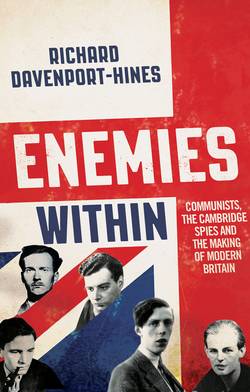

Читать книгу Enemies Within: Communists, the Cambridge Spies and the Making of Modern Britain - Richard Davenport-Hines - Страница 37

Walter Krivitsky

ОглавлениеKrivitsky was the link joining Oldham and King to Maclean and Philby. His original name was Samuel Ginsburg. He was Jewish and Russian-born, with a Polish father, a Slav mother and a Latvian wife who was a dedicated Bolshevik. In youth he was an active Vienna socialist while training as an engineer. After the launch of the illegal system in 1925, he became illegal rezident in The Hague, under the alias of Martin Lessner, an Austrian dealer in art and rare books. His house was furnished with stark minimalist modernity as visible support for his cover. He had enough culture to sustain the mask of connoisseurship. From the Netherlands Krivitsky directed much of the espionage in Britain. He became convinced of the insanity of Nikolai Yezhov, whom Stalin appointed chief of the NKVD in 1936 with the remit to purge the party. In 1937 Ignace Reiss @ Poretsky, the Paris-based illegal who was Krivitsky’s boon comrade, protested against the Great Terror and denounced Stalin. As a test of Krivitsky’s fealty, Moscow ordered him to liquidate Reiss. He refused, was summoned to Moscow for retribution and fled for his life to the USA.

It was at this time that a Cambridge luminary, the novelist E. M. Forster, wrote a credo that has been lampooned, truncated in quotation and traduced by subsequent writers. His remarks in their entirety carry a message of individualism, conscientious judgement and anti-totalitarianism that might have been a text for Whitehall values in the 1930s. ‘One must be fond of people,’ said Forster, ‘and trust them if one is not to make a mess of one’s life, and it is therefore essential that they should not let one down. They often do.’ Writing in 1939, when totalitarian nationalism was rampant, Forster continued: ‘Personal relations are despised today. They are regarded as bourgeois luxuries, as products of a time of fair weather which is now past, and we are urged to get rid of them, and to dedicate ourselves to some movement or cause instead. I hate the idea of causes, and if I had to choose between betraying my country and betraying my friend, I hope I should have the guts to betray my country.’ Krivitsky had the guts.31

The Americans were more obtuse about Krivitsky’s defection even than Dunderdale had been with Bessedovsky’s. He reached New York with his wife and children on the liner Normandie on 10 November 1938 (travelling under his real name of Ginsburg). Immigration officials rejected the family’s entry on grounds of insufficient funds. He was eventually released on bail provided by his future writing collaborator Isaac Don Levine, who had been born in Belarus, finished high school in Missouri and worked as a radical journalist but had become hostile to communist chicanery. Krivitsky funded his American life by producing articles and an autobiography which were ghosted by Levine and sold by Paul Wohl, a German-Jewish refugee who had worked for the League of Nations and was trying to scratch a living as a New York literary agent and book reviewer. In an article of February 1939 Krivitsky predicted the Nazi–Soviet pact seven months before it was agreed.

Roosevelt’s Secretary of State Cordell Hull had relinquished his department’s responsibility for monitoring communists and fascists to the Federal Bureau of Investigation in 1936: ‘go ahead and investigate the hell out of those cocksuckers’, he had told its chief J. Edgar Hoover. This decision left the FBI with the incompatible tasks of policing crimes that had already been committed and of amassing secret intelligence about future intentions and possible risks to come. In practice, the Bureau concentrated on law enforcement and criminal investigation rather than intelligence-gathering and analysis. This bias and Hoover’s insularity meant that there was more interest in pursuing Krivitsky for passport fraud than in extracting intelligence from him.32

After a nine-month delay, on 27 July 1939 a special agent of the FBI questioned Krivitsky for the first time in Levine’s office in downtown New York. Their exchanges were too crude to be called a debriefing. The debriefing of defectors is slow-moving at the start: character must be assessed, trust must be gained, affinities must be recognized and motivations must be plumbed. Only then, when the participants are speaking rationally and with the semblance of mutual respect, can reliability be gauged and evasions be addressed. Perception, patience and tact are needed to overcome psychological resistance and to elicit information that can be acted on. But the FBI agent did not engage in preliminary civilities to reach some affinity with his subject. Instead he fired narrowly focused questions about Moishe Stern @ Emile Kléber @ Mark Zilbert, who was believed to have run a spy ring in the USA. Krivitsky was diverted from volunteering information on other matters. When his replies contradicted the conclusions drawn in previous FBI investigations, or expressed his certainty that Stern had been purged, the special agent concluded that he was ill-informed, wrong-headed and obstinate. The FBI agent did not listen with an open mind; he would not revise his own presuppositions. Hoover dismissed Krivitsky as a liar.

Krivitsky’s memoirs In Stalin’s Secret Service had an ungrateful reception from reviewers: ‘his words are those of a renegade and his mentality that of a master-spy’, Foreign Affairs warned in response to his indictment of Stalinism. Communist sympathizers were especially hostile: Malcolm Cowley in New Republic decried the fugitive from Stalin’s hit-squad as ‘a coward … a gangster and a traitor’ to his friends, and elsewhere labelled him ‘a rat’. Edmund Wilson called Cowley’s review ‘Stalinist character assassination’; and certainly such tendentious pieces harmed Krivitsky’s credibility. The book was nevertheless read by Whittaker Chambers, a former courier for a communist spy ring in Washington who had turned against the Stalinist system of deceit, paranoia and executions, and had gone into hiding after being summoned to Moscow for purging. Later he was to write his own memoir, Witness, in which he presented the object of a secret agent’s life as humdrum duplicity. ‘Thrills mean that something has gone wrong,’ he wrote. ‘I have never known a good conspirator who enjoyed conspiracy.’ Chambers contacted Levine, who introduced him to Krivitsky. After the shock of the non-aggression pact signed by Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia on 23 August, Levine asked Assistant Secretary of State Adolf Berle to meet Chambers and hear his information.33

War in Europe began on 1 September: next day Chambers visited Berle and named eighteen New Deal officials as communists, including a Far Eastern expert at the State Department, Alger Hiss @ LAWYER @ALES, and Laurence Duggan @ 19 @ FRANK @ PRINCE, chief of the American Republics Division of the State Department. It is likely, but not certain, that the senior Treasury official Harry Dexter White was another of the communists denounced by Chambers. Berle reported the denunciation to President Roosevelt, who took no action, and waited seven months before alerting the FBI, which also took little action. In consequence of Berle’s inattention and the FBI’s laxity, Russian communist spies riddled the Roosevelt administration until the Cold War, damaged US interests and contributed to the post-war paranoia about communist penetration agents. Washington officials had an antithetical group mentality from their counterparts in Whitehall: most were political appointees; many were career lawyers; they lacked the procedures, continuities and group loyalties that were the pride of English civil servants; they had no administrative tradition of minuting inter-departmental meetings, and often avoided recording decisions on paper. Although more diverse in their backgrounds and less hidebound in their management, in handling Russian communist penetration of central government Washington’s oversights were as grievous as London’s.

The day after Chambers met Berle, on 3 September, Victor Mallet, Counsellor at the Washington embassy, wrote to Gladwyn Jebb, who was then private secretary to Sir Alexander Cadogan (Vansittart’s successor as PUS at the Foreign Office). Mallet noted that Krivitsky had foretold the Russo-German pact: ‘he is clearly not bogus as many people tried to make out’. Mallet reported Levine’s information that Krivitsky knew of two Soviet agents working in Whitehall: one was King in the Office cipher-room, who ‘has for several years been passing on everything to Moscow for mercenary motives’; the other man was said to be in the ‘Political Committee Cabinet Office’. (Levine was to recall in 1956 that when he told the British Ambassador in Washington, Lord Lothian, about two Foreign Office spies, Lothian smiled in superior disbelief.) Mallet warned Jebb, ‘Levine is of course a Jew and his previous history does not predispose one in his favour, as he was [newspaper owner William Randolph] Hearst’s bear-leader to a ridiculous mission of Senators to Palestine in 1936 and a violent critic of our policy. But … he seems quite genuine in his desire to see us lick Hitler.’34

Cadogan asked Harker of MI5 and Vivian of SIS to investigate the Communications Department. Vivian, with SIS’s patriotic mistrust of foreigners, thought Krivitsky sounded ‘at the best a person of very doubtful genuineness’. King stymied his questioners during his first interrogation on 25 September, without convincing Vivian, who ended by telling him, in the rational bromide style of such interviews, ‘We had hoped that you might be able to clear up what looks like a very unfortunate affair, and if you can at this eleventh hour tell us anything, it will, I think, be to everybody’s advantage. I don’t think you will find us unreasonable, but it is depressing to find that you have been unable to tell us anything, except the specific things we have asked you about.’ They detained King overnight in ‘jug’, to use the slang word of Cadogan, who noted on 26 September: ‘I have no doubt he is guilty – curse him – but there is absolutely no proof.’35

Spurred by the emphasis on national security that had followed the declaration of war on 3 September, and independently of the information received in Whitehall from Krivitsky, Parlanti approached the authorities of his own volition and volunteered his strange story of the Herne Bay train and the Buckingham Gate lease. Hooper’s denunciation of Pieck was resuscitated from a moribund SIS file. Decisively ‘Tar’ Robertson got King drunk in the Bunch of Grapes pub at 80 Jermyn Street, rather as he had done six years earlier with Oldham at the Chequers pub a few yards away. Robertson got temporary possession of King’s key-ring, which enabled MI5 colleagues to visit King’s flat in Chelsea and find incriminating material. King was arrested next day. On 28 September, under what Cadogan called ‘Third Degree’ questioning in Wandsworth prison, he gave a full confession. MI5 witnesses at his secret trial in October were driven to the Old Bailey in cars with curtained windows to hide their identity. There were no press reports of the trial, which was kept secret for twenty years. King was sentenced to ten years’ imprisonment.36

Harker and Vivian suspected several of King’s colleagues, but had no evidence for prosecutions. The ‘awful revelations of leakage’ appalled Cadogan and his Foreign Secretary Lord Halifax: in December 1939 they swept all the existing staff out of the Communications Department, although most remained as King’s Messengers, and installed a clean new team. Dorothy Denny and other women were appointed to the department to dilute its masculinity, and thus to moderate its office culture, although the top departmental jobs remained in male hands.

Then on 26 January 1940 SIS informed Cadogan that there had been leakages from the FO’s Central Department to Germany during the preceding July and August. On 8 February Cadogan persuaded William Codrington (chairman of Nyasaland Railways and of the London-registered company that held the Buenos Aires gas supply monopoly) to accept appointment as Chief Security Officer at the Foreign Office, with the rank of Acting Assistant Under Secretary of State and direct access to the PUS. One of Will Codrington’s brothers travelled across Europe for Claude Dansey’s Z Organization under cover of being a film company executive.37

Codrington was unpaid. He had no staff until in 1944 he enlisted Sir John Dashwood, Assistant Marshal of the Diplomatic Corps, ‘the most good-natured, jolly man imaginable’ in James Lees-Milne’s description. Dashwood handled the security crisis at the embassy in Ankara, where the Ambassador’s Albanian valet Elyesa Bazna, codenamed CICERO, filched secrets and passed them to the German High Command. Codrington retired in August 1945, resumed his City directorships and accepted the congenial responsibilities of Lord Lieutenant of the tiny county of Rutland. It is hard to imagine that he and Dashwood scared anyone who mattered.38

Meanwhile Krivitsky had been summoned by the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), then better known as the Dies Committee (named after its chairman, the Texan congressman Martin Dies). When he testified on 11 October 1939, naive and rude questions were pelted at him. One senator decried him as ‘a phony’, who ought to be deported. Krivitsky afterwards called HUAC ‘ignorant cowboys’ and Dies a ‘shithead’.39

There was a different assessment of Krivitsky in London. The star among Harker’s officers was MI5’s first woman officer Jane Sissmore: she had taken the surname of Archer after her recent marriage and was so precious to the Service that she had been kept in her job at a time when women civil servants were required to resign if they married so that they neither neglected their husbands nor continued to take a man’s place and salary. In November 1939 Archer convinced Harker that Krivitsky should be invited to London for debriefing. Krivitsky reached Southampton in January 1940, and was installed at the Langham Hotel in Portland Place under the alias ‘Mr Thomas’. Krivitsky’s four weeks of debriefing was MI5’s first experience of interrogating a former Soviet illegal about tradecraft, networks and names. As Brian Quinlan explains in Secret War, ‘The seamless nature of the debriefing’s planning and execution, the expertise and diligence of the officers who conducted it, and the quality and quantity of the information it produced have led some MI5 insiders to regard this case as the moment when MI5 came of age.’40

Krivitsky’s trans-Atlantic journey and accommodation in the Langham Hotel were tightly managed by his English hosts, who knew that a controlled but not oppressive environment improves the prospects of counter-intelligence interrogations. The FBI had waited nine months before interviewing Krivitsky and gave little forethought to the meeting. MI5 and SIS made meticulous preparations for his arrival at the Langham Hotel. They compiled preliminary character assessments of a kind that has since evolved and become standard operating procedure for defectors, foreign agents and foreign leaders. They exerted themselves to help Krivitsky’s wife and children, who were living in Canada while US immigration issues were resolved. Archer and her colleagues sought to impress Krivitsky with their understanding, competence and judgement. As Quinlan recounts, ‘their motivation was not simply pride; they understood that Krivitsky was a professional, and they hoped to gain his respect and cooperation by showing their own professionalism’.41

The debriefing was conducted by Archer, who was well informed about Stalin’s Russia and about Soviet espionage and approached Krivitsky from an international perspective. Her first task, which took several interviews, was to reassure him that he would not be arrested if he made admissions about spying on the British Empire. She then won his respect by her expertise in his field, and encouraged his explanatory candour by listening appreciatively to his account of all that he knew or had done. During debriefing, Krivitsky described the organization, tradecraft, tactics and personalities of the Fourth Department, the NKVD and the system of legal and illegal residents in the European capitals. He spoke of forged passports, secret inks, agent-training, penetration, counter-espionage and subversion in the British Empire. He predicted that in the event of an Anglo-Russian war the CPGB would mobilize a fifth column of saboteurs. Krivitsky made clear that the Stalinist aim was to support and fund colonial liberation movements, which would bring revolutionary change in territories under imperial rule and thus accelerate revolution in the west. He expressed ‘passionate hatred of Stalin’, Archer reported. It was his ‘burning conviction that if any freedom is to continue to exist in Europe, and the Russian people freed from endless tyranny, Stalin must be overthrown’.42

Krivitsky supplied new material on Oldham, Bystrolyotov, King, Pieck, Goold-Verschoyle and others. There were clues to the activities of both Maclean and Philby in his account. Krivitsky felt sure that the source of Foreign Office leaks was ‘a young man, probably under thirty, an agent of Theodore MALY @ Paul HARDT, that he was recruited as a Soviet agent purely on ideological grounds, and that he took no money for the information he obtained. He was almost certainly educated at Eton and Oxford. KRIVITSKY cannot get it out of his head that the source is a “young aristocrat”, but agrees that he may have arrived at this conclusion because he thought it was only young men of the nobility who were educated at Eton.’ Krivitsky imagined that since the announcement of the Nazi–Soviet pact in August 1939, ‘the young man will have tried “to stop work” for he was an idealist and recruited on the basis that the only man who would fight Hitler was Stalin: that his feelings had been worked on to such an extent that he believed that in helping Russia he would be helping this country and the cause of democracy generally. Whether if he has wanted to “stop work” he is a type with sufficient moral courage to withstand the inevitable OGPU blackmail and threats of exposure KRIVITSKY cannot say.’ No one connected the supposed Eton and Oxford aristocrat to Maclean, the non-Etonian, non-Oxford politician’s son.43

Krivitsky repeatedly alluded to a young ‘University man’ of ‘titled family’, with ‘plenty of money’, whose surname began with P. He was ‘pretty certain’ that this individual was in the same milieu as the Foreign Office source. In Archer’s summary of Krivitsky’s remarks, Yezhov had ordered Maly to ask this young Englishman – ‘a journalist of good family, an idealist and a fanatical anti-Nazi’ – to murder Franco in Spain. No one had the time to connect this information to Philby, who met many of the criteria but had no titles or fortunes in his background. It is usually forgotten that at the time of the Krivitsky interrogations Philby was working as a war correspondent in France and six months away from his recruitment to SIS.44

Doubtless at Vivian’s request, Archer omitted from her summary of Krivitsky’s debriefing all reference to Hooper, who had been rewarded for informing on Pieck by being re-engaged in October 1939 by SIS. Both Vivian and his SIS colleague Felix Cowgill trusted Hooper, and did not want him incriminated. Vivian insisted that Hooper was ‘a loyal Britisher’. Cowgill concurred that he was ‘above everything … absolutely loyal’. In fact Hooper was the only man in history to work for SIS, MI5, the Abwehr and the NKVD. He was sacked from SIS in September 1945, after post-war interrogations of Abwehr officers revealed that he had worked for them until the autumn of 1939.45

The earliest MI5 material supplied by Blunt to Moscow in January 1941 included a full copy of Archer’s account of debriefing Krivitsky. A month later Krivitsky was found dead, with his right temple shot away and a revolver beside him, in a hotel bedroom in Washington, where he was due to testify to a congressional committee. Moscow’s desire for revenge must have intensified after reading all that he had said in his debriefing, but suicide is equally probable. MI5 felt a moral responsibility to give financial help to his widow. Ignace Reiss had already been ambushed near Lausanne and raked with machine-gun fire in 1937. Joseph Leppin, Bystrolyotov’s courier for Oldham’s material, disappeared in Switzerland in the same year. The courier Brian Goold-Verschoyle was summoned to Moscow from the Spanish civil war and never seen again. Liddell’s informant Georges Agabekov vanished in 1938 – perhaps stabbed in Paris and his corpse put in a trunk that was dumped at sea, perhaps executed after interrogation in Barcelona, perhaps butchered in the Pyrenees with his remains thrown in a ravine. Theodore Maly, with his hands tied behind his back, dressed in white underclothes, kneeling on a tarpaulin, was shot in the back of the neck in a cellar at the Lubianka in 1938. Bazarov, who had been transferred from Berlin to serve as OGPU’s illegal rezident in the USA, was recalled in the purge of 1937 and shot in 1939. Bystrolyotov was luckier than these colleagues: recalled in 1937, he was tortured and survived twenty years’ hard labour in the camps (although his destitute wife and mother killed themselves). After Krivitsky’s death his refugee literary agent Paul Wohl told Malcolm Cowley: ‘We are broken men; the best of our generation are dead. Nous sommes des survivants.’46

George Antrobus was at home with his parents in Leamington Spa, celebrating his father’s eightieth birthday on 14 November 1940, when a bomb fell on their house – dropped by a German aircraft during the night of the great aerial blitz on Coventry. Antrobus and his father were killed. In the same week Jane Archer was sacked from MI5 for insubordination. Earlier that year, at MI5’s instigation, Vernon Bartlett, a diplomatic correspondent who had been elected as a Popular Front MP, tried without avail to inveigle Pieck into visiting London, where he would have been interrogated. Instead, in May 1940, Germany invaded the Netherlands, Pieck was taken into Nazi captivity and incarcerated in Buchenwald. Somehow he survived the barbarities of camp life, and resumed his design business in peacetime. In April 1950 he was induced to visit London for interview by MI5 about King. His clarifications may have contributed to a final death.

Armed with Pieck’s information, MI5 reinterviewed Oldham’s ex-colleague Thomas Kemp. Kemp, whose account of his contacts with Pieck was disingenuous, had been Lucy Oldham’s confidant and may have kept in touch with her. She had sunk towards destitution in the 1930s and spent the war years in the grime of Belfast, but in 1950 (aged sixty-seven) was living in a drab Ealing lodging-house. Perhaps because she was in desperate straits for money, perhaps after a tip-off from Kemp that MI5 were reinvestigating her complicity in the old treason, probably because both converging crises were intolerable, she drowned herself in the River Thames at Richmond in June 1950 before MI5 resumed contact.

Despite the determination of Antrobus, Cotesworth, Eastwood and Hay to coast through life with jokes, there was no laughter at the end.