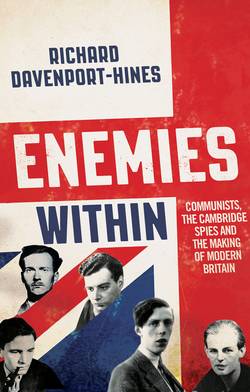

Читать книгу Enemies Within: Communists, the Cambridge Spies and the Making of Modern Britain - Richard Davenport-Hines - Страница 33

CHAPTER 5 The Cipher Spies

ОглавлениеThe Soviet Union’s earliest spies inside the Foreign Office are the subject of this chapter, which is avowedly revisionist. The security failings of the Office and of the intelligence services have been treated in the terminology of class for over sixty years. Public schoolboys supposedly protected one another in obtuse, complacent and snobbish collusion. The secrets of Whitehall were lost on the playing-fields of Eton, so the caricature runs. This, however, is an unreal presentation. The first Foreign Office men to spy for Moscow – in the years immediately after the disintegration of the Ewer–Hayes network – were members of its Communications Department. That department was an amalgam of Etonians, cousins of earls, half-pay officers, the sons of clergymen and of administrators in government agencies, youths from Lower Edmonton and Finchley, lower-middle-class men with a knack for foreign languages. Their common ingredient was masculinity. The predominant influence on the institutional character of the department, its management and group loyalty, its fortitude and vulnerability, all derived from its maleness. As in the Foreign Office generally, it was not class bias but gender exclusivity that created the enabling conditions for espionage. The Communications Department spies Ernest Oldham and John King, and the later spy-diplomatists Burgess, Cairncross and Maclean, had colleagues and chiefs who trusted and protected them, because that was how – under the parliamentary democracy that was settled in 1929 – public servants in a department of state prided themselves on behaving to their fellow men.