Читать книгу Unsolved - Robert J. Hoshowsky - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

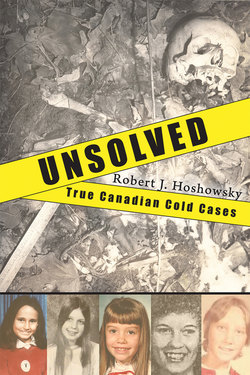

ОглавлениеChapter 2 Catherine Edith Potter and Lee Rita Kirk (1971)

ALL MURDERS ARE MONSTROUS, yet it is especially disturbing when the lives of children are taken, the reason — if there possibly can be one — for killing them is left unanswered. Cold cases remain open in police files, but solving them often proves to be far more difficult than many of today’s television shows and movies would have us believe. Forensic technology has made tremendous advancements over the years, but the detectives who relentlessly pursued the original investigations retire, leads evaporate, and police are faced with the urgency of solving recent homicides. Older cases may not be entirely forgotten, but unless there are some new developments murders that took place decades ago continue to languish in cardboard boxes in police storage units, silently waiting for new information to come along.

Back in 1971 two teenagers — Catherine Edith Potter and Lee Rita Kirk — were found murdered in a gravel pit in Pickering, Ontario, the motives for their deaths unknown. The girls were young; Potter was just thirteen, while Kirk was fifteen. The media has a habit of playing up where a victim was found, and soon Potter and Kirk became known not by their names but where their battered bodies were discovered. The mystery of the Gravel Pit Murders was born.

As with any investigation, police needed to retrace the steps that could possibly lead these two youngsters to where their remains were dumped; a shallow, weed-filled pit about three miles north of the Highway 401–Liverpool Road cloverleaf. Detectives quickly learned both Catherine and Lee were wards of the Children’s Aid Society, and had been living in a group home on Rochelle Crescent in Toronto. The couple supervising the girls, Mr. and Mrs. Robert McMaster, said they were good kids who caused no problems while in the home, where they lived along with four other youngsters. Both girls were in school, Catherine in grade eight at Woodbine Junior High School, and Lee in grade nine at Georges Vanier Secondary School. Both were described as carefree, and got along well with others in class.

(Ontario Provincial Police)

Just fifteen at the time of her murder, Lee Rita Kirk was found next to her friend Catherine Edith Potter in a Pickering, Ontario, gravel pit on October 3, 1971. She had been beaten and strangled.

The evening of Friday October 1, 1971, the pair ate a spaghetti dinner at the home of their foster family. Leaving the house around 6:30, the girls got a ride with their foster father and were dropped off at the corner of Yonge Street and Finch Avenue in the north end of Toronto. All the residents in the group home were free to come and go, but they were expected to say where they were heading and what time they’d be back. The girls had made plans to visit Kirk’s biological father in Richmond Hill that evening, and said they would return home no later than 11 p.m. It was an exceptionally warm night for October, 76°F, and the pair were going to take a bus the rest of the distance. When McMaster said goodbye to the two, there was no way he could imagine it was the last time he would see them alive.

(Ontario Provincial Police)

Catherine Edith Potter, thirteen, was found murdered alongside her friend Lee Rita Kirk.

When the girls hadn’t come back to the group home by 1 a.m., McMaster contacted a social worker. When there was still no sign of them an hour later the police were notified. It wasn’t like Catherine and Lee to not be home on time, or call. Police were concerned about the missing girls: for the past few years, a growing number of young women had been hitchhiking around the Toronto area and several of them had been robbed, beaten, or sexually assaulted. It was estimated in 1971 alone the number of Toronto-area rapes had increased by 10 percent from the previous year.

Shortly before Midnight on Sunday October 3, friends Albert and Vincent were walking in the area of Pickering Township’s Valley Farm Road, between the third and forth concessions. It was a popular spot for teenagers to hang out and drink, fool around, or ride their motorcycles and dune buggies. The two were on their way to watch some motorcyclists race on the trails when they cut through the gravel pit and found the missing girls, their bodies laying side by side behind some sumac bushes. Moving closer, they saw blood on the grass and a nearby concrete block. Catherine and Lee were dead. As soon as police were contacted the area was cordoned off. The apparent positioning of the bodies troubled police, because it looked as though the girls were killed somewhere else and dumped in the gravel pit next to one another.

After the bodies were taken to Oshawa General Hospital, they were sent to the Centre for Forensic Sciences in Toronto. When they were found, both girls were still dressed in their corduroy slacks and squall jackets, and there were no signs they had been sexually assaulted. Autopsies revealed one of the girls had been badly beaten. The official cause of death for both was asphyxia by means of ligature strangulation, meaning they had been strangled to death with something other than bare hands, possibly a rope, wire, or cord. There were no signs of drugs in their systems and tests of their stomach contents revealed the two had been killed approximately three hours after eating, placing the time of their deaths at around 9:30 p.m.

Further forensic examinations performed on the girls revealed some strange findings. The clothes of both Catherine and Lee had flecks of paint on them, in not just one or two hues but many different colours. Paint found on Catherine’s clothing was mainly the metallic kind popular on customized cars and motorcycles, including yellow, orange, red, and pale green. The same colours were discovered on Lee’s garments, along with dark green and dark blue metallic paint.

Under a microscope, investigators took samples from the sole of Catherine’s shoes, and found traces of silicon, aluminum, iron, and titanium. There were small silvery globs — the kind that drop to the floor when using a welding machine — clinging to the remains. Smudges of motor grease and light engine oil were found on the clothes and hands of both girls, along with a few grey wavy hairs. Bloodstains on the girls flowed from head to foot, indicating they were standing when beaten. To police, the evidence pointed to Potter and Kirk being murdered somewhere other than the Pickering gravel pit, probably an autobody shop or a garage. Considering the grease, oil, and paint particles, their bodies could have also been moved from the scene of their murder in a van or the trunk of a car. Soil stains on their clothes indicated the girls may have been dragged before being dumped into the gravel pit. Chemical analysts attempted to link the samples from the clothing to dozens of local garages and motorcycle repair shops, but were unable to find a match.

The question remained: how did the girls get from the north end of Toronto to a gravel pit in Pickering? Police believed that the two spent their bus fare on cigarettes — a new package of Export As was found in Lee’s pocket, with four cigarettes missing. They then hitchhiked and were picked up by the person or persons who killed them.

Within weeks, a $5,000 reward was posted by the Attorney General’s department for information leading to whoever killed Potter and Kirk. Police investigated one hundred tips from people who swore they remembered seeing the girls getting into cars not just in Toronto, but places like Port Perry and Whitby. Neighbours in the area of the gravel pit remembered seeing a later-model car parked with its lights on about a half mile from where the bodies were found. For some reason, their dogs seemed upset at that time, but since it was dark the residents weren’t able to gather any more information about the car.

At the time of their murders, police had difficulty locating the next of kin for both girls. The policy of the Metro Children’s Aid Society was to advise police — not the biological mother and father — when wards of the society were missing from foster homes. As a result, the biological parents of both girls were not told their daughters failed to return to the group home. Catherine’s mother discovered her daughter was dead when she heard about the murders on the radio. There was no money to pay for her young daughter’s funeral. She applied for and subsequently received $902 under the Compensation for Victims of Crime Act. The money was just more than enough to pay the funeral home, with $804 towards arrangements paid by the girl’s grandfather and $98 for other expenses.

In 1976, five years after the murders, police were still no closer to finding their killers, despite taking two thousand statements and interviewing 225 Toronto-area, known sexual offenders.

After almost four decades, the murders of Catherine Edith Potter and Lee Rita Kirk remain unsolved. A number of theories — ranging from the girls being killed as part of a motorcycle gang initiation to them dying at the hands of sexual perverts — don’t hold up. There were no signs of sexual assault on either girl, and motorcycle gangs are extremely unlikely to target two young girls for no reason whatsoever. Today, there is a $50,000 reward for information leading to the arrest and conviction of the person, or persons responsible for the deaths of these two young girls. Even after all these years, police believe there is still some hope of solving the Gravel Pit Murders.