Читать книгу Unsolved - Robert J. Hoshowsky - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

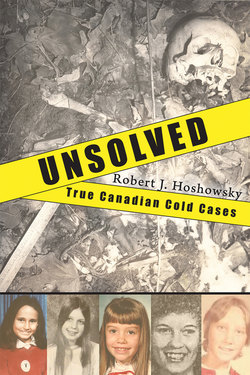

ОглавлениеChapter 1 Richard “Dickie” Hovey and Eric Jones (1967)

BACK IN 1967, THE WORLD WAS A vastly different place than it is today. While every generation can stake a claim to a decade as their own, anyone coming of age in the sixties remembers it as a period of unprecedented social change. In the United States, citizens were challenging not only themselves but their government and its policies as race riots were sweeping throughout the county, and fifty thousand men and women protested against the war in Vietnam at Washington’s Lincoln Memorial. In Canada, the country united in celebrating its centennial at Expo 67 in Montreal — and threatened to divide when French President Charles de Gaulle proclaimed “Vive le Québec libre!” (“Long live free Quebec!”), enraging English Canadians and sowing the seeds of separatism. Shouts of equal rights for all were heard as legions of young women, blacks, gays, and lesbians took to the streets, demanding respect. The generation gap was widening, as legions of bewildered parents realized that the expression “Don’t trust anyone over thirty” was not intended for someone else, but for them. Sons and daughters, wearing suits and dresses only a few years before, were discarding their sensible, conservative clothes for tie-dyed T-shirts, ripped jeans, sandals, and scraggly hair. It truly seemed as though the planet had changed overnight, leaving legions of exasperated parents and rebellious teenagers in its wake.

Across America a new age had dawned, and the cosmic epicentre was San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury district. Named after the intersection of the two streets, the Haight was the perfect place to rent a cheap apartment in one of the area’s massive, old wooden houses. A popular gathering place for students, poets, writers, musicians, and philosophers, the Haight soon became the beating heart of the counterculture movement in America. “Make Love, Not War!” was the chant of the young, as thousands of idealistic, wide-eyed teenagers converged on the area, lured by the promise of free love, cheap drugs, the right to free speech, and music many of them never imagined could even exist. Just a few years earlier, kids and their parents were listening to vinyl records by moral and non-threatening artists like Neil Sedaka, Connie Francis, Pat Boone, and Bobby Vinton. By the mid-sixties these acts were seen as antiquated and boring. A new musical tide was rising, led by reactionary musicians like the Grateful Dead, Janis Joplin, and the Doors, fronted by the sexually hypnotic and deeply disturbed singer-songwriter, Jim Morrison.

In the late sixties, rock ’n’ roll was still king but a new monarch was coming to court. Her name was Grace Slick, and her band was Jefferson Airplane. The release of the group’s innovative 1967 album Surrealistic Pillow was nothing less than a psychedelic sonic overload. Regarded today as one of the finest acid rock records ever recorded, Surrealistic Pillow spawned the hits “Somebody to Love” and “White Rabbit,” a two minute and thirty-two second aural experience referencing many of the otherworldly characters in Lewis Carroll’s book Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, such as the dormouse and the hookah-smoking caterpillar. The song became an anthem, if not the anthem, for the hippie generation. Back then, no one could predict that Jefferson Airplane would morph into Jefferson Starship before finally landing on the airways as Starship almost twenty years later with their pop hit, “We Built This City,” arguably one of the most reviled songs of all time. San Francisco, once the centre of the psychedelic universe, became, with breathless exclaim, “The city that rocks, the city that never stops!”

Back then it seemed as though the new ideals would last forever. It was a defining period in history, an age of sexual liberation that became known as the Summer of Love. For some Canadians, the year would be known not as a time of peace, love, and understanding, but for things dark, terrifying, and murderous. Over forty years later, many would come to remember Canada’s summer of 1967 as the Summer of Death.

Slender, energetic, and still just a boy at seventeen years of age, Richard James Hovey — “Dickie” to his friends — was one of the many thousands of young men and women who flocked to Toronto in 1967. America may have had San Francisco as its counterculture oasis, but Canada claimed its own musical Mecca in the streets of downtown Toronto. The States had bands like Jefferson Airplane and the Quicksilver Messenger Service, but Canada boasted plenty of its own talent, including future legends like Neil Young and Joni Mitchell, many of them playing live in Toronto’s Yorkville area. Hovey came from out east for the musical experience; others were hippies looking for a place to stay, or draft dodgers from the United States, who came because they didn’t believe in the war in Vietnam. Whatever the reason, Yorkville was the place to be that year.

(Ontario Provincial Police)

Richard “Dickie” Hovey, lead guitarist for Teddy and the Royals, with his prized guitar, an inexpensive Sears model that he painted white and modified to look like an expensive Fender. Hovey’s skeletal remains were not identified for almost forty years

Today, the area’s narrow, boutique-lined streets bear little resemblance to the Yorkville of forty years ago. The borders remain the same, decades after the sonic and cultural revolution of the sixties: Bloor Street to the south, Avenue Road to the west, and Yonge Street and Davenport Road to the east and north. The section near downtown is the home to a number of luxury hotels, condominiums, and countless famous designer shops like Vuitton, Boss, and Chanel, exclusive places where money is no object, and if you need to ask the price you should be buying somewhere else. One of the world’s top shopping destinations, rents in Yorkville are among the highest in North America today, averaging a minimum of several hundred dollars per square foot, depending on what side of the street you’re on.

In 1967, Yorkville wasn’t about expensive handbags, salons, and shoes, it was about the music. It was the place where countless Canadian artists got their start, like Murray McLauchlan and Neil Young. “You could walk down Yorkville Avenue and see Joni Mitchell on her front doorstep playing guitar,”1 said David Clayton-Thomas, lead singer for Blood, Sweat & Tears. Back then, Yorkville was a place without pretension, where you could go to any of the local European-style coffee houses or bars and sit for hours on end, listening to one great folk or rock artist after another. Yorkville was a veritable who’s who of music, where the country’s finest congregated: Young, Mitchell, Gordon Lightfoot, and Bruce Cockburn to name a few. Many American artists also flocked to play at one of Yorkville’s many clubs and cafes, like future funk legend Rick “Super Freak” James, Blues singer and guitarist Buddy Guy, and folk musician Mike Seeger.

The names of clubs soon became as legendary as the musical acts they hosted. There was the Riverboat, a coffee house featuring a mix of established and up-and-coming Canadian bands. Nearby were the Mousehole and the Purple Onion. One of the most famous was the Mynah Bird, known in equal parts for the calibre of the musical talent and the eccentricity of the surroundings. Yorkville had a lot of great clubs where you could catch the latest groups, but the Mynah Bird was the only one featuring a real talking bird, barely dressed go-go dancers grooving to the music, and live grass literally growing up the walls. The Mynah Bird was the place to see and be seen. It was also where Richard Hovey played his guitar for a few weeks back in 1967. Hovey’s style of dress was decidedly more mod than hippie. He kept his dark blond hair swept forward, and favoured turtlenecks, expensive-looking jackets, and narrow trousers over long, unwashed hair and sloppy clothes. When “Dickie” dressed in his royal blue jacket, his look resembled one of the early British Invasion bands that landed on the shores of North America a few years earlier, like the Kinks, the Beatles, or the Moody Blues.

Like many boys in their teens, Hovey’s face — with its high, arched eyebrows, turned-up nose, triangular jaw, smooth skin, and compact mouth — was still very delicate, almost feminine. As the Kinks song goes, he was a dandy, a handsome young man concerned with his appearance, and why not? At just five and a half feet tall, Hovey was not much larger than many of the girls who clamoured after him as he played guitar in Yorkville or back home in Marysville, a suburb of Fredericton, New Brunswick. Out east, Hovey had been playing lead guitar in a band called Teddy and the Royals since he was fifteen and still attending school. The group was popular, playing dances for local kids. They were named after Teddy Brown, the band’s eighteen-year-old vocalist; the “Royals” part of their name came from the clothing the five members wore onstage, sharp-looking royal blue jackets. The band was profiled a number of times in the local papers, complete with photos and references to one of their influences, Johnny Rivers, famous for his song Secret Agent Man.

For Richard Hovey, Marysville was home, the place where his family, friends, and bandmates lived, but Toronto’s emerging music scene was calling. When he left New Brunswick in 1967, Hovey hitchhiked his way to Ontario, taking few possessions except for a couple of dollars and his prized electric guitar. He was passionate about music and making it big, and if it was going to happen it was going to be in Yorkville. In time, the name Richard Hovey might have been mentioned in same venerated breath as Neil Young or Gordon Lightfoot, except that at some point in 1967, soon after arriving in Toronto, the young musician literally disappeared without a trace.

Most of Hovey’s friends from Marysville knew he’d gone to Toronto, and didn’t think it was strange when they didn’t hear from him, at least not for awhile. It was the sixties, after all, and travelling across the country for weeks at a time wasn’t all that unusual back then. Still, some of his family and friends became concerned when the weeks turned into months without a word, not even a letter, a long-distance collect call, or even a hastily-scribbled postcard. Some assumed Hovey settled down and was living a normal life in Ontario, but his parents, Melvin and Phyllis, weren’t so sure. Melvin took his concerns about Richard to the local branch of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, but for reasons unknown the information was never properly filed as a missing persons report. His parents knew their teenaged son made it to Toronto, guitar in hand, but what became of him? Years went by, turning into decades of uncertainty over the young man’s fate. Melvin passed away in 1991, followed by Phyllis in 2003. Both parents went to their graves never knowing what happened to their son. It would be almost forty years before young Richard Hovey’s fate, and name, would be revealed.

On May 15, 1968, a farmer was plowing his field in Tecumseth Township near Schomberg, about twenty-five miles north of Toronto. It was an isolated area, surrounded by tall grass, dense brush, and overgrown trees, certainly not a place you’d go to unless you had a very good reason. Troubled by a foul smell he thought was coming from his septic tank, the farmer went to investigate and saw something that would haunt him forever. Near a rusty wire fence in a hedgerow were the rotting remains of a young man. The naked body, reduced by decay, insects, and animals to a skeleton, was laying face down in the earth. A few pieces of dried, blackened skin could still be seen here and there, and some hair still remained on the scalp. Although almost all the flesh was missing, a white shoelace remained intact, tying the hands of the body behind its back. With no signs of clothing present and the hands restrained, this clearly was no accidental death.

As disturbing as the discovery was, it was part of a larger problem: this was the second body found in a remote area, in a similar advanced state of decay. On December 17, 1967, less than six months prior to the remains being discovered by a farmer near Schomberg, the skeletal remains of another male were uncovered in a lonely, wooded area of Balsam Lake Provincial Park, about ninety miles north of Toronto, south of Highway 48, near Coboconk, Ontario. In time, Ontario Provincial Police would refer to this body as the “Balsam Lake Victim.” Forensic tests revealed the remains were those of a young man, likely fifteen to eighteen years old, twenty-two at most. It was believed the remains had lain in the same spot for about six months. A forensic examination revealed that the teeth were in exceptionally good condition, and had recent fillings in the left and right lower first molars. Remaining hair on the head was straight, light brown, and of medium length. Unlike the discovery near Schomberg, this skeleton displayed a number of unusual characteristics. Instead of twelve thoracic vertebrae, this body had a thirteenth vertebra, and an additional thirteenth rib on the right side. If these physical anomalies were known to the victim’s family or friends, it could help identify the remains.

Like the body found near Schomberg, this young man was also naked. No clothing was found except for a pair of white, low-cut, size seven, tennis-style shoes made in Czechoslovakia. The hands were tied together, just like the other victim. Instead of binding the hands with a shoelace, however, they were tied with an eleven-foot length of twine. The remains were those of a small man, no more than five feet three inches tall. Police did not know the identity of either of these nameless young victims, yet they were united in many ways, like brothers in death.

“The bodies were linked by victimology,” said David Quigley, a deputy inspector with the Ontario Provincial Police and lead investigator in the cases. Details about both young men, along with those of many other cases, are online as part of the OPP Resolve Initiative, a website created in 2006. In partnership with the Office of the Chief Coroner, the site features hundreds of cases, divided into missing persons and unidentified bodies/remains. In just a few years, the Resolve Initiative has become a successful example of the powers of the Internet, generating hundreds of tips from the public, and receiving between four and six thousand hits per month.

From time to time, the OPP reviews cold cases, such as the unidentified remains found near Schomberg and the skeleton discovered close to Coboconk. For almost four decades, the unclaimed bodies of these two young men sat on a shelf in numbered boxes at the coroner’s office in Toronto. Both victims had much in common: they were male, small, likely still in their teens, and found in secluded areas within the same general time period, late 1967 to mid-1968. The hands of both victims were bound, and since no clothing was found except for a pair of tennis shoes in the area of the Schomberg victim, the murders appeared sexual in nature. As part of the resurrected investigation, Quigley and other officers revisited the places where the bodies were found, armed with metal detectors and original crime scene photos. The hedgerow near the farmer’s field had grown over in the decades since the first body was discovered, but it was recognizable, and looked about the same way it did back in the sixties — still isolated, and not a place likely to attract much attention.

The Ontario Provincial Police soon presented details of the crimes to the media, along with the faces of the deceased victims. Using the actual skulls, a forensic artist carefully placed tissue depth markers and layers of clay to reconstruct the faces, which were displayed at an OPP press conference in late 2006, almost forty years after the two sets of remains were found. The heads and neck were visible, and both wore simple white dress shirts, one with stripes, the other checks. The faces were young and boyish looking underneath brown wigs that sat atop the heads of both victims, their expressions wide-eyed and not quite human, almost frozen with terror.

A major crimes investigator and forensic artist with the Canadian Forces National Investigation Service, Master-Corporal Peter Thompson spent hour after hour applying clay to the skulls of the deceased, rebuilding the faces in the hope that someone could identify them and finally give them back their names. Thompson was known to the OPP for some time for his composite drawings, many of them based on witness descriptions of bank robbers and kidnappers. Although he was accustomed to creating sketches of criminal suspects this was the first time in his career that Thompson did three-dimensional reconstructions.2 Before he could begin working for the OPP, Thompson had to receive permission from his superiors at the Canadian Forces. Once the chain of command gave their approval, Thompson met with the OPP, who presented him with photographs of the skulls and old crime scene photos of the remains. These were essential to providing the artist with a sense of the tools he would require — and the many challenges he would face — recreating the faces of the dead.

“With three-dimensional reconstruction, skulls have to be in good condition, and be able to bear the weight of the clay,” said Thompson, who painstakingly examined, measured, sketched, photographed, and catalogued the remains from the moment he received them. If the skulls were damaged he likely would have created a drawing instead, a two-dimensional reconstruction of the faces. Fortunately, the remains were stable enough to tolerate handling and the application of depth markers and clay.

Thompson was thoroughly prepared to recreate the faces of the two dead boys. He is quick to credit the forensic techniques taught to him by two of his key instructors when he was learning his craft at “the Academy,” the Federal Bureau of Investigation in Quantico, Virginia. A fast learner, Thompson was fortunate enough to study under artists widely considered legends in the field of forensics: Betty Pat Gatliff and Karen T. Taylor. Gatliff, a retired medical illustrator, teaches forensic art workshops on facial reconstruction using actual human skulls, and operates her own studio, Skullpture Lab, in Norman, Oklahoma. Among her many credits, Gatliff did clay reconstructions of some of the decomposed victims of John Wayne Gacy, one of America’s most notorious serial killers. Her work allowed a number of families to give their dead sons proper burials.

Taylor’s background is no less impressive than that of her fellow instructor. Credited with coining the term “forensic art” in the 1980s, her qualifications include working as a portrait sculptor at Madame Tussauds Wax Museum, and as an instructor at the FBI Academy for over twenty years. The classes Peter Thompson took with Taylor and Gatliff were his only formal art instruction, and he said his natural ability to draw came from his father.

(Master Corporal Peter Thompson, Canadian Forces National Investigation Service)

Forensic facial reconstructions of two young men who were recognized years later as Eric Jones (left) and Richard “Dickie” Hovey. The actual skulls are beneath the layers of clay.

The forensic reconstruction process, said Thompson, is a cooperative one between the police, the coroner’s office, and the artist. Meeting with the coroner in Toronto where the skeletal remains of both young men were housed, Thompson performed intensive assessments on the bodies. Although he had the training to identify bones as being male or female, an anthropologist measured the bones as they lay on a table, and compared the measurements to photos taken in the sixties.

Remaining true to his FBI training, Thompson avoided putting any “ego” into his work. He omitted any details or embellishments that could mislead anyone viewing the completed reconstructions, keeping them as simple as possible. Before applying any clay to the skulls he did a detailed preliminary examination, noticing both victims had an overbite of the bottom teeth. This detail was crucial, and the faces were deliberately created with the mouths slightly open, “So that people who would view the reconstructions would be able to see the teeth, and perhaps that would trigger some recognition.” Once the faces were completed the two victims looked like brothers, young men united in death.

(Master Corporal Peter Thompson, Canadian Forces National Investigation Service)

The skull of Richard “Dickie” Hovey with depth markers attached. His skeletal remains were found in an isolated area of Tecumseth Township near Schomberg, about twenty-five miles north of Toronto, on May 15, 1968.

After finishing his work, Thompson remembers hoping to God that someone would recognize the young men, and be able to give a name to the mysterious remains that sat shelved in boxes for almost forty years. His silent prayer was answered when a friend and a family member, independent of one another, viewed media coverage of the reconstructions and contacted the OPP. One of the clay-covered skull photographs seemed hauntingly familiar, resembling a long-lost relative and friend who left home for Toronto back in 1967. Members of the OPP travelled to New Brunswick and, after obtaining blood samples from family members, confirmed that one set of remains were those of Richard Hovey, the handsome young guitarist missing for almost forty years. A name could finally be placed to the “Schomberg” remains found in May 1968, just one day after what would have been Hovey’s eighteenth birthday.

Although the positive identification of the body provided some degree of consolation to Hovey’s family and the police, many questions remained unanswered. What was the identity of the other young male found in the desolate forest of Balsam Lake Provincial Park? How did these young men arrive at their final destinations? When were they killed, and how? What happened to Hovey and the other male during the last hours of their lives? Were there other known victims, living or dead? Most important of all: who killed them?

(Master Corporal Peter Thompson, Canadian Forces National Investigation Service)

A profile view of the skull of Richard “Dickie” Hovey with depth markers attached.

Although police will not confirm any specific suspect or suspects in the murders, it is known that young men were targeted by a serial sexual predator in the Church and Wellesley area of Toronto back in 1967. Just as Yorkville was a haven for musicians in the sixties, so was the downtown Church/Wellesley section the heart of the city’s growing gay village. Today, the area is an immensely popular tourist destination for gays, lesbians, the transgendered, drag queens, and the merely curious. Regarded as “the Gay Mecca of Canada,” the place was not nearly as open or friendly in the sixties. Back then, the area was frequented by young men who feared the police morality squad and gangs of gay bashing teenagers more than being picked up by an overly aggressive sexual partner. Yellowed, old newspapers of the time reveal articles about one man who frequented the area, and remains the most likely suspect in the murders.

Now in his early seventies, James Henry Greenidge fits the pattern of murders in an eerily perfect way. Presently behind bars in a British Columbia prison, Greenidge — who has since changed his name to James Gordon Henry — is by all accounts a model prisoner with a surprisingly high IQ. During his many years in prison, Greenidge hasn’t touched drugs or gotten himself into trouble. He has completed the Intensive Sexual Offender Program, and is known to be helpful and cooperative with staff. Reportedly, he has spent much of his time tutoring other inmates, yet it remains uncertain how many of them, if any, are aware of the staggering, unimaginable brutality he committed in the past.

The crimes perpetrated by Greenidge are not just disturbing, they are truly horrifying — rivalling those committed by the character Jame Gumb, better known as “Buffalo Bill,” in the book and film, The Silence of the Lambs. At least there is some solace to be had in the knowledge that Gumb is fictional; Greenidge is all too real, and considered to be Canada’s first serial killer. His early life — like that of many youngsters who grew up to become pattern killers — was rife with abuse, abandonment, neglect, and a barely contained temper that unexpectedly rose to a boil. At the age of five, Greenidge developed tuberculosis and was sent to a sanatorium, where he was forced to clean toilets. Soon after, he began a pattern of running away and stealing. At one point, he was raised by a strict aunt whose child rearing skills included physical and mental torment. The young Greenidge frequently fled his so-called home, and was sexually abused at reform school.

Over the years, Greenidge’s body grew, and so did his uncontrollable fury. By the age of sixteen he was working as a “hustler,” a male prostitute, and began to demonstrate incredibly violent sexual tendencies. In time, he would blame much of his behaviour on his aunt, who allegedly told him of the dangers of being a male Negro in society, and of the lynchings of young black men that took place in the American South. According to parole records, Greenidge viewed himself as a lonely and isolated individual, a victim of racism — or so he said — and someone who needed to protect himself at any cost. The biggest threats to his life, his aunt told him, came from associating with “white women or homosexuals.” Tragically, Greenidge took her words seriously. In his teens, he was exhibiting a high degree of narcissism and sexual sadism, which he inflicted on girls and boys alike, all of them white. Although still young, his violent, sadistic streak was far from satiated — it was just beginning.

In 1955, Greenidge, then eighteen years old, was sentenced to ten years for viciously attacking and raping a fourteen-year-old girl in Toronto. Examined by psychiatrists at the time, the teenage Greenidge demonstrated a “defect in personality,” was deemed irresponsible, and showed no sign of wanting to reform. A hospital laundry worker, Greenidge was arrested a mere twenty-one hours after the attack, following the announcement of a reward. At the trial, the jury took only one hour and fifteen minutes to reach their verdict of guilty. The pronouncement was not surprising, considering the brutal circumstances of the attack.

In what would amount to the greatest understatement of the judge’s career, Greenidge was told, “I don’t think you are safe to have around.” The young black man showed no signs of remorse, or wanting to reform. The teenaged girl was walking home with a bag of groceries when Greenidge grabbed her, dragging her kicking and screaming down an alleyway. He then proceeded to sexually assault her, choking her at the same time, almost to the point of death. Even veteran police officers, men who had witnessed all kinds of depravity, were thoroughly repulsed by the viciousness of the attack on the helpless girl. All her clothes, right down to her shoes, were ripped from her body, which was left beaten, bloodied, and desecrated. Fortunately, the girl was able to give a remarkably detailed description of her attacker, “a husky Negro,” about five feet eight inches tall, eighteen years of age. At his trial, Greenidge, the one-time art student and church choirboy, complained the confession was beaten out of him at a police station. No one cared to listen.

Tragically, the rape was only the start of Greenidge’s life as a sexual predator and unstoppable violent offender. After his parole in 1960 he was unable to control his rage and continued his pattern of becoming violent in mere moments. In 1965 Greenidge nearly choked a man to death, believing he was responsible for helping to put him behind bars. Characteristic of the viciousness of his attacks, Greenidge beat the man, dragging him one hundred feet into a laneway to continue the assault. He had his hands around the man’s throat when neighbours saw the horrific assault taking place and called the police. In a sickening twist, he almost pummelled the wrong man to death. The mistaken identity assault landed Greenidge in a reformatory for six months, while his victim was sent to hospital to recover from his serious injuries.

Undated photo of convicted killer James Greenidge, who later changed his name to James Gordon Henry. He was first convicted of violent crimes in the fifties, and is presently behind bars in British Columbia for the horrific murder of a young woman in 1981.

Although just in his twenties, Greenidge had spent years of his life in jail and was rarely out on the streets for long before being sent back behind bars. In 1967 he was sentenced to seventeen years for a number of horrific crimes. He nearly killed one man he’d picked up in Toronto’s gay village. Another victim, seventeen-year-old Robert Wayne Mortimore, wasn’t so lucky. Mortimore’s naked, tattooed body was found in a field northeast of Markham, Ontario. The young insurance clerk was reported missing on July 11 by his brother, and his decomposing remains — missing in the heat of summer for over a week — had to be identified through fingerprints and part of a birth certificate found in Greenidge’s car. One of Mortimore’s tattoos said “Born to raise hell,” while another was a dagger, dripping blood. A number of items were missing from the body, including a silver ring with the initials R.M., a second ring with a black stone, a chain with a gold cross, and a pair of blue and white mod-style trousers.

At the time of Mortimore’s murder, Greenidge was already serving time for the attempted murder of a twenty-one-year-old man who he left beaten, naked, and bleeding in a field. The pair, said Greenidge, met at a movie theatre known as a gay pickup place and drove out to the country on a gravel stretch of road to a farmer’s field north of Barrie, Ontario. The man then made the mistake of asking Greenidge for twenty bucks, allegedly for sex. This threw him into a rage. Pouncing on his victim, Greenidge began punching, kicking, and stabbing the man repeatedly in the throat and chest with a penknife. He then bound the man and left him naked, alone, and bleeding to death. Police said that if the man had not been found within a few hours, he surely would have died.

When he was released from prison in 1978, Greenidge changed his name to James Gordon Henry. His name was different, but his sexual rage remained as strong as ever. In Winnipeg he was charged with sodomizing a thirteen-year-old boy, who he then tried to strangle to death with a blanket. The charges against Greenidge were stayed. While out of jail, Greenidge killed his last known victim in 1981. He was sentenced to life in prison for the brutal rape and murder of Elizabeth Fells, a twenty-four-year-old prostitute. Picking up the woman, Greenidge drove her to an isolated spot in the woods north of Vancouver and flew into a rage. Raping the woman, he then stabbed her over and over again, slashing her throat and leaving her barely alive in an isolated area, repeating his unremitting pattern of violence. Somehow, Fells managed to crawl to the side of the Squamish Highway and flagged down a passing car. She died in hospital eight days after her horrifying attack, but lived long enough to give police a detailed description of her attacker: James Henry Greenidge. Her statement helped police capture Greenidge, who was arrested and charged with her murder.

Over the years, many people fell victim to Greenidge’s rage: women, men, and children. They all have one thing in common: they were white, like Richard Hovey and the young man found at Balsam Lake. The lives of these young men were cut tragically short and no one, save for their killer or killers, knows what the last moments of their lives were like, dying naked in an isolated area with no one there to save their lives.

Thanks to the skills of forensic artist Master Corporal Peter Thompson, the remains formerly known as the Balsam Lake Victim finally have a name. On March 9, 2009, police revealed his identity. The skeletal remains found near Coboconk, Ontario — with the extra thoracic vertebra and rib — were those of Eric Jones from Noelville, Ontario. The original forensic estimate of his age was accurate: Jones was just eighteen when he died. Once the identification was made, police were able to create a profile of the young man and the circumstances that may have led to his death. If it were not for one of Jones’s sisters watching a television program she rarely viewed, her brother’s body would likely have remained unidentified forever.

(Ontario Provincial Police)

Ontario Provincial Police reward circular for Eric Jones, whose skeletonized remains were found in a wooded area of Balsam Lake Provincial Park on December 17, 1967.

In February 2009, W-Five aired a special about Richard Hovey and the other unidentified remains. Pauline Latendresse, one of Eric’s sisters, happened to turn on the television program that day and immediately recognized the clay reconstruction of her long-lost brother’s face. Excited, she began phoning her siblings, telling them to “watch it, watch it right now.” The next day, police came by and collected DNA samples from family members. Tests soon confirmed the remains were those of the missing Eric, son of the late Napoleon and Alexina Jones.

Through interviews with surviving family members, police were able to reconstruct the life and final days of Eric Jones, who came from a large family of eleven children. An older brother, Oscar, remembered the last time he saw Eric. It was at a wedding for one of their sisters in April 1967. By this time, Eric had moved to Toronto to live with an aunt and look for work as a dishwasher, returning for his sister’s wedding. The brothers argued about Eric quitting school and moving away from home. Tragically, it would be the last time Oscar saw his brother alive.

Described by his family as a bit of a shy kid and a loner, Eric wrote letters back and forth to his sister Pauline for about six weeks after he arrived in Toronto. One day, the letters she mailed to her brother came back unopened and unread, marked “No such address.” The aunt Eric was living with in Toronto had moved to Montreal, taking his belongings with her. Since she had not seen or heard from the eighteen-year-old, she assumed he moved back to Noelville. The missing man’s sister contacted police agencies across the province and was led to believe that Eric, a solitary sort, probably didn’t want to be in contact with his family. His sister never believed her brother would want to estrange himself from the family and hoped to see Eric alive again some day. That day never came, and once the remains were released, Eric Jones was buried next to his parents.

(Ontario Provincial Police)

The skeleton of the Balsam Lake victim, estimated to be about fifteen to twenty-two years of age at the time of death. For years, police hoped the remains would be identified due to some unusual physical anomalies, such as an additional thoracic vertebrae and a thirteenth rib on the right side.

Since reopening the cases of Hovey and Jones, the OPP have aggressively investigated leads in the decades-old cases. A $50,000 reward has been announced for information leading to an arrest of the person or persons who murdered Jones and Hovey. Police believe the dead teenagers are only two of five young men who were abducted, bound, sexually assaulted, and slaughtered.

Back in 2006, OPP investigators spoke to Prime Timers — a gay social seniors group — at a special meeting in Toronto. Displaying Thompson’s forensic reconstructions of the two then-unidentified young men, police hoped viewing the faces might help someone remember who they were, and where and when they were last seen. Since that time, police have determined that Richard Hovey — whose remains were found near Schomberg — was last seen alive in Yorkville, in 1967, getting into a light blue Corvair driven by “a muscular black man.” It is believed Jones also got a ride with the man in the same model car.

Convicted sex killer James Henry Greenidge drove a light-coloured Corvair, which was used to identify him by a surviving victim, the twenty-one-year-old who Greenidge beat, stabbed, and left for dead in a farmer’s field north of Barrie. Ironically, the car driven by Greenidge was deadly in more ways than one. The Corvair remains one of the most dangerous vehicles ever made, with a tendency to oversteer, overheat, skid wildly out of control, lift, or worse, flip over. The car was so dangerous it became the first chapter of the book by lawyer and consumer advocate Ralph Nader, Unsafe at Any Speed. More than merely hazardous, driving the car could be fatal, leading Nader to call its design, “One of the greatest acts of industrial irresponsibility in the present century.”3 For Greenidge, the car suited his personality: fast, powerful, unstable, and potentially deadly.

The similarities between the murders and Greenidge’s modus operandi are too many to ignore. The FBI classifies three types of serial killers: organized, disorganized, and mixed. Organized killers are methodical, and often have an above average IQ. Disorganized killers have a lower than average IQ, and rarely take the time to cover their tracks or dispose of a body. The disorganized killer is unlikely to have his own vehicle, usually relying on other forms to transportation, like public transit or walking. If he does have a car it is likely to be messy and not in good working order. Organized offenders usually have their own means of transportation, keeping it in top condition. Perhaps most telling is the way organized killers operate. Unlike the disorganized offender, the organized killer takes along their own restraints, such as a rope and handcuffs, during their hunt for their next victim.

In many ways, criminologist and noted FBI serial killer tracker, Robert K. Ressler, might have been writing about the killer of Hovey and Jones when he wrote his book, Whoever Fights Monsters:

Taking one’s own car, or a victim’s car, is part of a conscious attempt to obliterate evidence of the crime. Similarly, too, the organized offender brings his own weapon to the crime and takes it away once he is finished. He knows that there are fingerprints on the weapon, or the ballistic evidence may connect him to the murder, so he takes it away from the scene. He may wipe away fingerprints from the entire scene of the crime, wash away blood, and do many other things to prevent identification either of the victim or of himself. The longer a victim remains unidentified, of course, the greater the likelihood that the crime will not be tracked back to its perpetrator. Usually the police find the victims of an organized killer to be nude; without clothing, they are less easily identified.4

Police are investigating Greenidge in connection to yet another unsolved murder of a victim who has yet to be named. On July 16, 1980, a motorist pulled his car off the side of a rural road in the town of Markham, Ontario, ostensibly to relieve himself. It was around 8:30 p.m. and getting dark. The area around the Eleventh Concession north of Steeles Avenue was much like it is today, semi-rural, full of woods and dense brush, and sparsely populated with farms and houses. The man walked about seventy-five feet from the road into the woods when he made an unnerving discovery. On the ground were the skeletal remains of a human body. Unlike the bodies of Hovey and Jones, found decades earlier, this time police found a significant amount of clothing lying on the earth next to the skeleton. But considering that the bones turned out to be those of a male, the items were not quite what police expected to uncover.

All the garments and accessories were women’s clothing. Police discovered a red blouse, a pair of size thirty women’s blue jeans, a pair of red and pink high-heeled shoes, short white frilly socks, and a woman’s powder compact complete with a mirror. All the items led investigators to believe that the remains were those of a transgendered male or a cross-dresser, someone who likes to wear clothing from members of the opposite sex.

Although the body had been reduced to a skeleton and disturbed, likely by animals, forensic examiners were soon able to determine that they belonged to a small male about five feet three inches to five feet five inches tall. Even without flesh a great deal can be revealed about someone from their skeletal remains, such as approximate age, sex, physical stature, and race, known as “the big four” to forensic anthropologists. Our bones and teeth reveal vast amounts of information about our age through the epiphysis, caps on the ends of long bones that fuse completely once we leave our teens. Epiphysis on bones in other parts of the body, such as the clavicle, fuse later in life, around age thirty. From then on, signs of bone loss, deterioration, and work-related injuries become more evident. Someone who lays bricks or pours concrete for a living will have a much different bone structure and density than another person who works as a personal assistant in an office.

Tests of the bones revealed that the Markham victim was white, and about twenty-five to forty years of age. In life, the man would have been small with an extremely light build — somewhere between one hundred and 120 pounds at the most — and a thin, even gaunt, face. Considering the weathered condition of the boney remains, the body and clothing would likely have been in the woods for about two years by the time they were found, placing the time of the man’s death at around 1978. The time frame coincided with a period when Greenidge was out of jail.

It is believed the victim wore the items found around him at one point, but was not wearing them at the time he died. Later testing revealed there were no signs of decay inside the clothes, such as the socks and pants, which meant the man was left to die naked in the woods, women’s clothing on the ground beside his body. Since the body had been reduced to a skeleton, investigators at the time were unable to determine an exact cause of death. Police say the remains did not reveal any signs of edged weapons being used or blunt force trauma. Could the Markham victim have been strangled, as was the case with many of Greenidge’s other victims? Police aren’t saying.

(York Regional Police)

A museum quality facial reconstruction of the face of the Markham victim, unveiled in December 2009. Found off the side of a rural road in the Town of Markham, Ontario, on July 16, 1980, it is estimated that the body remained undiscovered for two to three years. The victim, a male twenty-five to forty years old, is believed to have been transgendered or a cross-dresser and has yet to be identified.

Adding to the mystery is the question of what became of the remains of the Markham victim? Unlike the bodies of Richard “Dickie” Hovey and Eric Jones, which sat properly stored in numbered boxes at the office of the coroner in Toronto for decades, the unidentified male discovered in the woods was, for some unknown reason, buried in a pauper’s grave at Toronto’s Mount Pleasant Cemetery on Christmas Eve 1983, along with the clothes. The reasons for interring the remains and the female garments found near the body have not been revealed.

In 2007 the cold case of the mysterious Markham victim was resurrected by York Regional Police and the skeletal remains — which had been buried in the cemetery for years — were disinterred and reexamined using the latest available technologies. “We felt that it was necessary to exhume the body,” said Douglas Clarke, a homicide detective-constable with York Region. “We had photographs but we didn’t have the actual items.”5

The initial belief by police at the time the body was discovered was not that this was the body of someone who was murdered, but a young male who wandered into the brush and died, or the unfortunate victim of a car accident. The original coroner’s report is confusing, and allegedly states the man was possibly struck by a car, sailing over the road and into the trees, where his body remained for several years until it was found in 1980. The notion has since been revised, since it doesn’t take the obvious question into consideration: why would the victim of a hit and run be found naked in the woods, with clothing near his body? It is not unusual for the victim of an auto accident to literally be knocked out of their shoes by the tremendous force of the impact, but to suggest that the rest of the clothing — jeans, socks, and blouse — would also be wrenched off is absurd, and makes one question the professionalism of anyone foolish enough to suggest such a ridiculous scenario, or allow the clothing to be buried with an unidentified body. York Regional Police have revised the earlier notion that these are the remains of an accident victim, and now believe the young man met his demise as a result of foul play.

Following the exhumation of the remains, police were able to obtain something not available to them at the time the bones were discovered in 1980: DNA. Even though the technology exists, there was still no guarantee that precious DNA would be recoverable. The body had been in the woods for at least two years by the time it was found, and subjected to insect activity, animals, wind, rain, the blistering heat of summer, and the ice and snow of winter. Conditions following burial at Mount Pleasant Cemetery would have been better, but only slightly, since the skeleton would still face the cold and damp conditions of the grave.

Fortunately it was possible to extract DNA from the disinterred bones and teeth, which was collected and compared with missing persons reports across the province. York Regional Police recently had a close call with the family of a missing gay man from Montreal. The physical description was very close and the man disappeared around 1978, approximately the same time as the male victim died in the Markham woods. Hoping for a break in the cold case, Detective-Constable Clarke drove to Montreal and obtained a blood sample — unfortunately, it wasn't’ a match to the remains. Police are hopeful that the DNA sample they now have on file can be used to compare the Markham victim’s remains to those of a living relative, and that one day a match will be made.

(York Regional Police)

A recent artist impression of the male Markham victim, based on clothing found near the body in 1980. In life, the man was no more than 120 pounds and five and a half feet tall. A red blouse, women’s blue jeans, red and pink high-heeled shoes, frilly, white socks, and a woman’s powder compact led police to believe the body was that of a male cross-dresser.

Like Hovey and Jones, the victim found in 1980 recently had a clay bust recreation made of his face, which was unveiled to the media and posted online at the York Regional Police website in December 2009. Considering the actual skull that the reconstruction was based on had been buried for many years and became damaged and misshapen due to extreme cold, the final result is remarkably lifelike. The three-dimensional clay portrait was sculpted by an artist after the skull was scanned using a brand new technology, and is so accurate that it has already been described as museum quality.

“We hope it looks pretty close to this and that someone comes forward,” said Clarke, who unveiled a drawing to the media of what police believe the victim looked like in life: a slender, effeminate-looking young man with dark hair about four inches long, wearing red and pink, pointy-toed, high-heeled shoes, white frilly socks, form-fitting blue jeans, and an open-collared, red, short-sleeved blouse.

“It’s my belief that he was transgender, possibly in the sex trade down in the Toronto area which … was a bit of a haven, in the 70s, for gays,” said Clarke, who also speculated that the young man may have come to Toronto years ago to live his life as part of the city’s large gay, lesbian, and transgendered community. “In my opinion, I think he was picked up in the city, taken to [Markham], endeavours occurred and then he was killed and left there,” repeated the detective-constable, calling the wooded area “a dumping ground.”6

Considering the viciousness of his earlier crimes and his repeated pattern of picking up young men in downtown Toronto, driving them to remote areas, assaulting and choking them, then leaving their naked bodies to rot in the wilderness, all eyes are looking once again at the seventy-two-year-old James Henry Greenidge. Currently serving his time at a prison in British Columbia for the horrific 1981 murder of young Elizabeth Fells, Greenidge was denied parole in 2007, but has another shot at freedom in 2010. Some may feel Greenidge is an old man who has served his time; others, especially police, victims’ rights groups, and Toronto’s gay community, would rather see the muscular man who preyed upon and brutalized so many smaller and weaker individuals than himself leave prison not in a cab, but a body bag.

“This is just one of at least three cold cases involving victims with ties to Toronto’s gay communities,” stated Xtra! following the unveiling of the clay reconstruction of the face of the Markham victim. “In two other cases, forensic sculptures, like the one of the Markham man, have led police to identify long-nameless victims.”7 As one of Canada’s leading gay and lesbian newspapers, Xtra! has published a number of stories over the years into the investigations of the murders of Hovey and Jones, and any possible connection to James Henry Greenidge, and the attacks on other young gay men in Toronto in the sixties and seventies.8

Back in 1977, Greenidge was transferred to a minimum security institution in Ontario. During that time, he went on numerous, unescorted weekend passes, presumably to visit a friend in Toronto. It is believed Greenidge only visited his friend one time, leaving many other weekends during that year unaccounted for.

Over the years, Greenidge, the model prisoner, has come up for parole a number of times. Although considerably older than he was in the late sixties during the Summer of Love, many police officers consider him as dangerous as ever if he is released back into society. Although police have re-interviewed Greenidge, he is unlikely to admit any involvement in the murders that occurred while he was free and out on the streets. If he killed these young men it will remain a secret, one he will take to his grave.

Back in 1967, Richard Hovey was just one of thousands who made the migration to Yorkville’s music scene. Some old-timers still remember him, the sharp-looking kid full of talent and musical promise. Back east, his former bandmates from Teddy and the Royals kept a reel-to-reel tape of their band practice from the mid-sixties. The reel was tucked away in an attic for decades and has made the technological transference over the years from reel-to-reel to cassette tape, then onto CD. It contains several original songs by members of the group, with titles like “I Love You So” and “You Say That You Love Me.” They were recorded over forty years ago, alongside cover versions of songs like “19th Nervous Breakdown” and “Satisfaction” by The Rolling Stones, “Nowhere Man” by the Beatles, and “Heart Full of Soul” by the Yardbirds.

In an old black and white photo, Hovey is pictured standing alongside his bandmates holding his prized guitar in his right hand. The instrument was his pride and joy. Although it was just a plain-looking electric guitar he’d bought at Sears, Hovey painted it white and modified it to look like an expensive Fender. Left hand in his pocket, he is pictured wearing a dark suit and white turtleneck, his hair is combed forward in a mod style. He has the wide-eyed look of a boy trying to be a man, someone whose life was full of promise. Friends suspected that dream would never come true when he failed to pick up his guitar from the Mynah Bird back in 1967. The people who knew him realized he would leave just about anything behind, but not his guitar, not even if his life depended on it.

While reconstructing the faces of these two dead boys, forensic artist Peter Thompson remained clinical and dispassionate. For him, Hovey finally became real when he listened to the CD of old some songs by Teddy and the Royals, recorded in mono, which have a haunted, otherworldly sound to them. “And that’s when I went, ‘Oh my God,’ because you’re hearing this man, Mr. Hovey, actually do something in the past. The hairs stood up on the back of my neck, and at no other time did I feel that way, until I heard him playing his guitar.”

After Hovey’s remains were identified, Thompson spent four hours — “from 9 a.m. to 1 p.m.” according to his notes — carefully removing all the clay and hair from the skulls of the two young men he had so painstakingly applied, the boys who would later be identified as Richard “Dickie” Hovey and Eric Jones. Bit by bit, the clay and depth markers came off, until nothing remained but two whitish skulls, smiling up at him. By the time Thompson was finished, the remains looked exactly the way they did when he received them. The process of giving these teenagers their faces back had been meticulously documented on paper and in numerous photographs, from the moment they arrived at his office in boxes sealed with police tape to the moment of completion. It simply wasn’t necessary leave the clay in place any longer. Thompson worked on the two reconstructions for about a month while working on another major case, and now his job had come to an end. One thing was certain: he could not give these young men their lives back, but after forty years he helped give them their names. The skull and bones were no longer those of strangers, but two teenaged boys brutally murdered sometime during the Summer of Love.

Hovey’s remains were carefully packed into a box, sent back to his family in New Brunswick, and buried next to his mother and father. His killer remains at large, but at least now Richard James Hovey is home again.