Читать книгу Unsolved - Robert J. Hoshowsky - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

We are each of us responsible for the evil we might have prevented.

— James Martineau

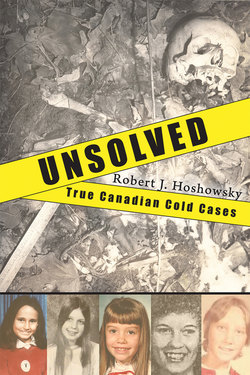

WRITING A BOOK ABOUT UNSOLVED crimes — as I have found out — is a physically, spiritually, and emotionally unsettling experience. Over the course of researching and writing Unsolved: True Canadian Cold Cases my thoughts kept going back to a well-known character from Greek mythology by the name of Sisyphus. Condemned by Zeus to Tartarus — a monstrous place deep below the underworld — his punishment was to roll an enormous boulder up a hill, only to have it tumble back down the steep slope time and time again, for all eternity. The task was maddening, repetitive, unforgiving, and without end. For families of the murdered and the missing whose crimes remain unsolved, every re-examination of their case, every anniversary marking the death or disappearance of their loved one, every tip or clue that starts out promising but eventually leads nowhere, keeps bringing them back to the very same spot they started years before.

When someone is murdered or vanishes, never to be found, a void is left behind that never completely closes. There is something especially cruel about unsolved crimes and the pain that comes from not knowing who took the life of someone you love, why they were killed, and what happened to their remains. For the parents and surviving siblings, life the way it was before the crime comes to a sudden stop and can never be the same again. Even years later, the slim hope that their missing youngster is alive and might still be reunited with their family keeps coming back, as do the thoughts that they are likely dead, and that their bodies may never be recovered.

Sometimes, families of victims learn about new developments in their case when a piece of evidence is uncovered, forensic facial reconstructions unveiled, hidden genetic information revealed through DNA tests, or long-silent witnesses come forward to tell their story. Identifying skeletal remains after many decades, as in the case of Richard “Dickie” Hovey and Eric Jones, may bring families some satisfaction, but never closure. Reuniting missing family members and burying them alongside other relatives fills in large pieces of the puzzle but not the whole picture, especially if the person who took their life remains unapprehended and unpunished. In some instances, families talk to cold case detectives every few years about their case, resurrecting every single painful detail over and over again. Did they have any enemies? Were they involved with drugs, or gangs? Was there anyone who paid your child too much unwanted attention? Did they have any unpaid debts, or gambling problems? Can you think of anyone who would want them dead?

The families portrayed in Unsolved have given countless interviews to the media — often on the anniversary of their brother, sister, mother, father, or child’s death or disappearance — and remain cautious, even guarded, about their emotions, never allowing themselves to become too excited about potential “new breakthroughs” or “exciting developments” in the crimes. Being hopeful is one thing, and being realistic is something else entirely. If tips come forward in their cold case it’s easy to get caught up in the anticipation that the guilty will be brought to trial, and after so many years justice will finally be served. If the information leads nowhere, as often happens, and there is no resolution, the boulder rolls back downhill to the foot of the mountain, families gather the pieces of their soul, and the rebuilding process starts all over again.

When someone’s life comes to a violent, abrupt end, the mourning process for the family members is fractured and incomplete. There is nothing natural or normal about murder. Losing a family member slowly over time allows grief to come in stages, not all at once, as those left behind struggle to prepare themselves for the inevitability of death. A loved one lost to homicide often creates overwhelming feelings of anger, grief, and guilt that can consume people for the rest of their lives. The shock is sometimes too much to bear, and no two people experience emotions the same way or for the same amount of time. Just as there is no statute of limitations on murder, there are no rules for how long someone will feel the pain, frustration, fear, and fault when someone they care about is killed. Some take solace in their faith, believing in a higher power and the thought that they will eventually be reunited in the afterlife. For others, friends and family endlessly repeat overused phrases like, “It is God’s will,” and, “Time heals all wounds,” are of little comfort, as many question why a supreme being, if one exists, would allow someone they love to die such a brutal death.

Fortunately, there are numerous victims’ rights groups that provide assistance to grieving families of murder victims. Some, like the Toronto Police Victim Services Department, offer material on resources, support groups, and the police investigative process. For many families the officer in charge (OIC) becomes their lifeline, the person they can call upon to find out where the investigation into the homicide of their family member stands. While some simply want to know when the person who took their relative’s life is caught, others want to be as much a part of the entire criminal process as possible, from investigation to arrest, and trial to sentencing. Those left behind to mourn are sometimes called homicide survivors. They are the other victims of crime, the living relatives of the dead whose rights have, for many years, been forgotten by society or ignored altogether. The Canadian Resource Centre for Victims of Crime poignantly states the realities facing families of murder victims: “No amount of counselling, prayer, justice, restitution or compassion can ever bring a loved one back.” The emotional reactions some of these survivors have — including shock, guilt, anger, and depression — can lead to adverse physical symptoms, such as nausea, nightmares, increased blood pressure, and loss of appetite. Dealing with other family members, friends, and co-workers can become difficult, sometimes impossible. If these symptoms last a month or more following the murder, it is possible to be diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

The number of families that fall apart after the death or disappearance of a loved one cannot be calculated. Some will stay together for months, even years, while others — especially parents of murdered children — blame their partner or surviving sons or daughters for not “being there for them,” and not protecting the victimized child from a violent predator. Many couples divorce and surviving children sometimes become estranged from one another, as attention focuses on the dead instead of the living.

Wherever possible, I conducted interviews with family and friends of missing persons and murder victims for Unsolved. Very early on I was amazed at how many were not just willing but eager to talk, sharing not only their memories but their feelings, often of guilt, anger, and remorse.This often meant resurrecting painful details about how their loved ones died. The reason for many of them: to keep the stories of the dead and missing alive and let the world know they are not forgotten — and neither are their killers.

Following a homicide many people become involved in the process. There are the families of the victim, friends, witnesses, and police who investigate the crime. There are the detectives, the searchers, volunteers, and the media, who often play a large part in disseminating details about the crime and the possible suspects. Trying to catch a killer is a complicated process involving police working on many levels. There are the uniformed officers who are often the first to arrive and cordon off areas to protect the integrity of the crime scene, which can be as small as a room or as large as several city blocks. There are the detectives who come in and direct officers to search here and there, or go door-to-door to find witnesses, anyone who heard or saw anything that could help in the investigation. In the case of a missing child, there are the officers who go wherever the search takes them, from police divers in the muddy waters of an old gravel pit to abandoned buildings, dense forests to rundown rooming houses. Depending on the case there are often countless people involved in trying to catch a killer, including forensic artists, private investigators, ballistics experts, child find and missing persons agencies, and pathologists.

Writing a book about unsolved cases brings with it a host of challenges. There is the need to ask the cold, dispassionate, and often grisly specific questions: How long did it take them to die? What type of weapon was used? What was the exact cause of death? Was the weapon recovered? Were they sexually assaulted? These types of questions were best left to police officers, veteran detectives, private investigators, and others possessing first-hand knowledge of the crime. Family and friends of murdered and missing persons were better able to fill in details about their loved ones and his or her personality traits, likes, dislikes, successes, failures, goals, and aspirations.

The genesis of Unsolved was in conversations I had with some of the talented editors at Dundurn, namely Michael Carroll and Tony Hawke. After the publication of my first book, The Last to Die: Ronald Turpin, Arthur Lucas, and the end of Capital Punishment in Canada, in 2007, I had a number of ideas for my next project. Several outlines were written, and a number of ideas were tossed back and forth. One of them was suggested by Tony: “Why not write a book about unsolved crimes?” Tony is perhaps one of the most knowledgeable people I’ve ever met when it comes to the subject of Canadian mysteries, having overseen and edited countless books on strange goings-on in Canada. He possesses not only genuine warmth of character but an almost childlike enthusiasm and eagerness for potential projects. A number of older cases were mentioned, such as the unusual circumstances surrounding the 1917 death of artist Tom Thomson, the unexplained disappearance of Toronto theatre magnate Ambrose Small in 1919, and the mysterious murder of millionaire Sir Harry Oakes in his Bahamas mansion in 1943. All were mesmerizing cases about larger than life figures who have become an integral part of the Canadian consciousness over the decades, and a collection of these old stories would surely become a valuable reference book.

At the time my feelings were mixed. Having a familiarity with all of these cases, I know that all of them have been the subject of numerous books published over the years, along with documentaries, movies, plays, even entire websites devoted to a single case. I was reluctant to write a book about these and other older crimes unless I could bring something new to the reader, as I had with my first book, such as previously unknown letters, hidden or suppressed government documents, never before published photographs, or interviews with individuals who had not spoken to the media in decades, if at all.

My interest as a writer has always been bringing together stories from the past with interviews from the present. After several weeks of searching through my own memory, missing persons websites, true crime blogs, police cold case websites, newspaper files, books, magazines, archives, and talking to friends, I began working on an outline for a book on Canadian crimes, which eventually became Unsolved.

All writers, from first-timers to professionals, need guidelines and structure, or their work is likely to float off into the heavens like an untethered balloon. To satisfy my needs, I came up with a number of parameters for all of the cases. It didn’t matter if the victims were male or female, rich or poor, known or unknown, or if their deaths or disappearances were widely covered in the press at the time or have been forgotten. The words still solvable kept echoing through my head as I was researching and writing this book, and I settled on a timeline: no case could be more than approximately forty years old. The rationale behind this? Even if a case is decades old, there is still a chance the killer — even if he or she is now a senior citizen — can still be caught and convicted. Assuming a murder or disappearance took place back in the late sixties, there could still be people who remembered the victim or victims, as was the case with Richard “Dickie” Hovey and Eric Jones, who recalled seeing these young men getting into a car with a stranger, most likely their killer. All the murders and disappearances in this book are still open, and in many cases, leads continue to trickle in to the police years later.

Unsolved is unlike many other true crime books. There are many things it is, and many things it is not. It was never my intention to create an “encyclopedia” of unsolved Canadian crimes, since such an endeavour for one writer — let alone a team of writers, researchers, editors, proofreaders, photographers, and fact checkers with years to spare and an unlimited budget for resources — is simply not possible. Across the country, there are literally thousands of cold cases waiting, pleading to be solved, some of them going back decades.

Many major police departments in Canada have websites devoted to unsolved cases and murder suspects, including the Royal Canadian Mounted Police.In Toronto,the Homicide Squad Unsolved Cold Cases website (www.torontopolice.on.ca/homicide/unsolvedcold.php), which went online in 2008, currently features dozens of cases along with summaries of the crimes, photos, maps, videos, applicable reward and contact information, and other related materials. It is their intention to post hundreds of other unsolved murders on the site, estimated between three hundred and 350, going back to 1957, the year Toronto Police Service was formed. The number of hours required by police, computer technicians, web designers, and others to write the summaries, scan and post the photos, update, and maintain the website is tremendous. The Resolve Initiative, a website created by the Ontario Provincial Police (www.missing-u.ca), works in partnership with the Office of the Chief Coroner. Featuring hundreds of cases, divided into missing persons and unidentified bodies/remains, the site went online in 2006 and receives thousands of hits per month. These sites, regularly updated and maintained, provide up-to-the-minute accounts of cold cases that cannot possibly be covered in one book.

Likewise, Unsolved is not a traditional “anthology” that true crime aficionados are accustomed to reading. Unlike the majority of compilations, which assemble dozens of short, previously published articles, usually culled from newspapers or magazines, into book form, all the cases presented here are original, researched and written expressly for this book, and have never been published in any other form — book, magazine, or on any websites — until now. During the course of researching and writing this book every effort has been made to paint as complete a picture as possible, from the time the crimes took place to the present day. In a number of cases new information was made available shortly before the book was published and has been incorporated into Unsolved. This need to include information that is as up-to-date as possible resulted in several unavoidable delays, and I am grateful to my publisher, Dundurn, for realizing the importance of presenting this material in the book.

Books based solely on repackaging old stories are informative — and heaven knows my shelves are full of them — yet they all suffer from one serious drawback: the author rarely, if ever, updates the material, in effect leaving the reader with an incomplete snapshot rather than a full portrait. In my opinion, this does a tremendous disservice to the reader, the victim, and his or her family. All cold cases going back forty years can be updated, even if tips are few and far between. Over time, police will often release information that wasn’t made available years earlier in the interest of generating more coverage about a particular cold case, such as the disappearance and murder of Veronica Kaye in 1980. A significant piece of evidence, a small metallic button found underneath her skeletal remains in 1981, was not released to the public until almost thirty years later, in 2009. In the case of Hovey and Jones, their unidentified skeletal remains sat in boxes at the office of the coroner for almost four decades, until the Ontario Provincial Police retained the services of a forensic artist, Master Corporal Peter Thompson, from the Canadian Forces National Investigation Service. Over the course of several weeks Thompson painstakingly applied depth markers, clay, and false eyes to the skulls until they became faces once again. As a result, the remains of both young men were soon reunited with their families, yet their murderer remains at large.

Readers may remember some widely publicized stories, such as the brutal 1983 rape and murder of nine-year-old Sharin’ Morningstar Keenan. The only suspect in her murder, Dennis Melvyn Howe, remains at large. The search for Howe was one of the largest in Canadian history, taking police to remote locations across North America, from mining camps to a cemetery in Sudbury, Ontario, to exhume the remains of a man believed to be Sharin’s killer. Although Howe has not been caught, his face is etched into the minds of many Canadians through wanted posters and news coverage, and Toronto Police continue to receive tips about the case to this very day.

Some cases, such as the unexplained disappearances of fourteen-year-old Ingrid Bauer in 1972 and eight-year-old Nicole Louise Morin in 1985, remain unsolved despite massive searches by police and volunteers, age-enhanced photos and illustrations depicting what they would look like as adults, rewards, and the distribution of thousands of missing persons posters. At the time they disappeared the Internet was many years away. Today, their names and the details of their cases are being kept alive through video re-enactments on YouTube, and information posted on police websites, the Doe Network, and Child Find, to name a few.

One of the greatest challenges in writing a book about unsolved crimes is deciding which cases to include. And what happens if a case you’re writing about is solved? As someone with a keen interest in true crime since childhood, I grew up reading about a number of the crimes in this book and have wanted to write about them for a long time. Others were suggested by police officers and representatives from missing persons organizations. I also received numerous emails from friends and families of murdered and missing persons who heard about my upcoming book via the Internet, and have tried to include these cases where possible.

A number of cases I originally intended to include in Unsolved were, in fact, solved during the time I was researching and writing, most notably the May 2007 murder of multi-millionaire and philanthropist Glen Davis. I originally intended to contrast the Davis homicide with another case, the unsolved 1998 murder of businessman and Obus Forme founder, Frank Roberts. Both men were enormously wealthy but came by their millions in entirely different ways. Davis was the son of Argus Corporation chairman Nelson M. Davis and inherited a vast fortune when his father died in the pool at his Arizona home in 1979. Roberts was a self-made man who, following a tennis injury, invented a unique back support that found its way into thousands of homes and offices across Canada.

Both Davis, sixty-six, and Roberts, sixty-seven at the time of his death, were enormously rich but had completely opposite public personas. While Roberts embraced the limelight, Davis eschewed it completely, except on those rare occasions when it helped to promote awareness of his favourite environmental charities, like the Sierra Club and the World Wildlife Fund. The thrice-married Roberts was the father of two sons, a daughter, and had thirteen grandchildren; Davis was married to the same woman for years, and had no children. Tragically, the larger than life Roberts and the shy, unassuming Davis both met their ends violently. Roberts was gunned down in the West Toronto parking lot of his factory, while Davis was shot to death in a North Toronto underground parking lot. Immediately, the lives of both men were plastered across newspaper headlines and stories were a muddied mixture of fact, rumour, and innuendo. Were the murderers dissatisfied business associates from the past? Did a jealous husband order the hit? Were large corporations, whose very existence depended on logging, mining, and other activities that destroy wildlife behind the slaying of Glen Davis?

In both cases, the line between fact and fantasy quickly became blurred in the media and online, as reporters exposed the professional and personal lives of Davis and Roberts. In many ways, Davis was the world’s luckiest man. Left with an empire worth $100 million, he cheated death. The first time was in 1983, when he survived an airplane fire that claimed twenty-three lives, including Canadian folk musician Stan Rogers. The second was in 2005, when he was savagely attacked outside his Toronto office by a man wielding a baseball bat. The third occasion, in the parking garage on the afternoon of Friday May 18, 2007, Davis’s luck ran out. As a youngster I knew Davis — albeit not very well — and remember speaking to him at length soon after he survived the fire that broke out aboard Air Canada flight 797. Davis was a soft-spoken and decent individual, and as of this writing several men, including Davis’s first cousin once removed, have been charged in connection with his senseless homicide. In the end, it appears the motive for his murder had nothing to do with conspiracy theories about big businesses versus environmentalists, but money, which he willingly gave away in the millions to help causes to benefit humanity.

Unsolved crimes present us with a kaleidoscope of emotions. Intriguing and infuriating, I believe that some of the cases in Unsolved still have a chance of being solved, even years after the murder or disappearance took place. Time and technology can sometimes be an advantage in cold cases. As the years pass, witnesses may recall details that seemed unimportant at the time or feel more comfortable approaching police with information because they no longer fear reprisal. Scientific advances, such as DNA technology, have given new life and renewed hope to solving many cold cases, as seen in the case of Susan O’Hara Tice and Erin Harrison Gilmour. In life, Tice and Gilmour never knew one another and had very little in common. A recently divorced mother of four children, Tice moved back to Toronto from western Canada in the summer of 1983, and was brutally murdered soon after. Just a few months later, attractive, single socialite Erin Harrison Gilmour, just twenty-two, was murdered in her Yorkville apartment. Both women were raped and semen recovered from the crime scenes was subjected to DNA testing seventeen years later in 2000, revealing the same man was responsible for killing both women. The murders of Tice and Gilmour remain unsolved, yet their killer’s genetic fingerprint is on file.

Technology has dramatically advanced the way police search for suspects, going far beyond the days of wanted posters papering the walls of police stations and post offices. Just as criminals have kept pace with technology, so have police agencies, which frequently use the latest tools to apprehend criminals. It is not uncommon for police to incorporate social networking websites like YouTube and Twitter to inform the public and the media about murder or bank robbery suspects, or help locate missing children. As technology progresses, friends and families of murder victims also pay tribute to their lost loved ones through websites like MySpace and Facebook.

This book has been an emotional experience from the beginning, and I cannot say “from beginning to end,” since there is no end, at least not yet. Unsolved crimes don’t reach their conclusion with the death or disappearance of a loved one, they reach their end with the perpetrators being caught. Even in cases like the murder of Sharin’ Morningstar Keenan where there is only one suspect: Dennis Melvyn Howe. For many people, the case will never be closed until he is located, alive or dead.

My intention with this book is to keep the names of the murdered and the disappeared alive, and possibly resurrect memories from someone, anyone, who has information in whoever committed these crimes so that they can be brought to justice.

Every effort has been made to paint as complete a picture as possible, from the times the crimes took place to the present day. In a number of cases new information was made available shortly before the book was published and has been incorporated. All the cases in this book should be here and deserve to be solved, not just for the victims but for the families left behind.

One final note: Some of the cases in this book have been the subject of numerous theories; a few of these theories are plausible, while others are highly unlikely. Unsolved is based on facts made available to the author up to the time of publication. In order to create as accurate a picture of the crime(s) and subsequent investigation(s) as possible, a number of these theories are included in the book. They are clearly stated as “theories” or “speculation” in the text and are not the belief of the author or the publisher. They have been included to provide the reader with the greatest amount of knowledge possible about each case.

Visit Robert J. Hoshowsky’s website at www.truecrimecanada.com.