Читать книгу Palisades - Robert O. Binnewies - Страница 17

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

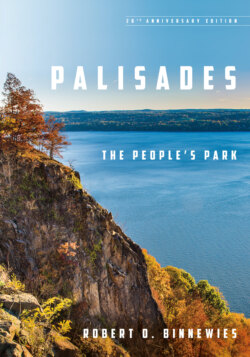

Harriman

ОглавлениеCOMMISSION EYES UNDERSTANDABLY were focused on the vexing daily challenges of the New Jersey Palisades when, in November 1907, an article appeared in the Outlook magazine entitled, “The Preservation of the Highlands of the Hudson First Publicly Advocated by Edward Lasell Partridge, M.D.” Partridge was looking beyond traprock quarries and toward the locally known “highlands,” a spectacular segment of the Hudson River fifty miles upriver from New York City where the river cut through the northernly extension of the Appalachian Mountains. Rising near Mount Marcy in the Adirondack Mountains, the Hudson River cascades and descends for about a hundred miles to Fort Edwards, New York, then flows leisurely south for another hundred miles to the highlands bulwark at West Point. There, following a course bulldozed long ago by glaciers, the river narrows, deepens, and gains speed as it rushes through a sweeping twenty-mile S-turn past Bear Mountain before once again taking on a broad, stately flow down to its rendezvous with the Atlantic Ocean.

Early Dutch voyagers, tacking under sail against the current and wind in the “narrows,” with threatening rocky bluffs abeam on port and starboard, referred to this section of the river as the “Devil’s Horse Race.” Henry Hudson managed to sail through the narrows to the upriver “gate” just above West Point, anchored, briefly explored, and then turned back, ending his quest for the fabled northwest passage to China. Continental Army defenders fortified the heights of this natural bastion and floated a massive chain across on barges from shore to shore in an attempt to stop shipborne assault by the British. And, decade upon decade, the narrows has attracted tourists who marvel at the scene and artists who try to capture its intricate beauty on canvas, paper, film, and microchips.

Partridge proposed that a sixty-five-square-mile section of the highlands, with the narrows as its centerpiece, be declared a national park. He noted that Civil War battlefields at Gettysburg, Chickamauga, and Shiloh had been preserved by the U.S. government in a manner that included the protection of scenery, forests, fields, and historic buildings and argued that the military installations at West Point and other Revolutionary War sites in the narrows deserved similar congressional favor. In his vision of a park, Partridge proposed nature-education programs, scenic roads, and preservation of “wild woodlands.” He suggested tax incentives to encourage the protection of private land interests within the park boundary.

Partridge’s conservation plea carried the weight of his reputation as an honored leader and teacher within New York City’s medical community. His home was on the northern slope of Storm King Mountain at Cornwall-on-Hudson, just upriver from the narrows gate. The landscape design for the Partridge estate was courtesy of Frederick Law Olmsted, and his home was filled with art and historic objects. He served as the chair of Obstetrics at the College of Physicians and Surgeons and had an interest in philanthropic activities that included support for the New York Institution for the Education of the Blind, the Washington Square Home for Friendless Girls, the Huguenot Society, the American Scenic and Historic Preservation Society, the Society of Colonial Wars, the Garden Club of America, the Constitution Island Association, the Grant Monument Association, and the New England Society of New York. This robust man, who relished “light” lunches of two sandwiches, a thermos of coffee, and pie, took great delight in opportunities to pursue and influence public policy.

Among the landowners whom he was seeking to influence with his national park idea were Mr. and Mrs. Edward Henry Harriman. The Harrimans owned thousands of acres in the highlands and knew of Dr. Partridge as an acquaintance and respected neighbor. They took careful note of the Outlook article. Only two years later Mrs. Harriman would sweep the startled Interstate Park Commission forward to astonishing land stewardship responsibilities, influencing conservation initiatives across the nation.

Born in 1848, Edward H. Harriman, one of eleven children, “started with nothing” and became the “mightiest” railroad baron, according to biographer Rudy Abramson. Harriman built a railroad empire including the Union Pacific, Southern Pacific, and Illinois Central that controlled 75,000 miles of track and employed more men than the standing army of the United States. Named for a great uncle who was forced to walk the plank in a Caribbean pirate raid, E. H. was the son of a minister who settled in West Hoboken, New Jersey. His father became rector of St. John’s Episcopal Parish, a position that paid $200/year, after returning from a misadventure in the California gold fields. A side benefit was that sons of the rector could attend the prestigious Trinity School in Manhattan. Harriman and his brothers would walk two miles to a ferry landing, cross the Hudson, and walk another mile to school. E. H. Harriman ranked first in his class at Trinity but dropped out at age fourteen to work as a copyboy at the brokerage firm of D. C. Hays. Promoted to pad boy, the fleet-footed Harriman raced from office to office, calling out the latest stock quotes. He favored his memory over the quotes scribbled on his pad and won admiration from the brokers for never making a mistake. Within eight years, Har-riman had moved up in the Wall Street environment, so much so that he was able to buy a seat on the New York Stock Exchange. He gained a reputation as an outstanding trader, but was found to be a “loner, secretive and relentless” by some of his peers.

In 1879, he and Mary Averell were married. Biographer Abramson wrote:

About the same time he was courting Mary, he struck up an equally fortuitous friendship with Stuyvesant Fish, who would eventually help him get his start in big-time railroading. It was, to put it mildly, an unlikely alliance. Fish’s family had been pillars of New York commerce and society for two hundred years. Stuyvesant’s father, Hamilton Fish, had been Governor of New York, a U. S. Senator, and more recently President Ulysses S. Grant’s Secretary of State. Grandfather Nicholas Fish had served under General Washington from the Battle of Long Island to Yorktown.

Fish was physically large and easygoing. E. H. was “scrawny, near sighted, and cunning as a wolf,” Abramson said. Stuyvesant Fish was on the board of directors of the Illinois Central Railroad, a company that controlled tracks extending through America’s heartland from Lake Erie to the Gulf of Mexico. In 1881, a stock swoon caused by the assassination of President John Garfield prompted Harriman to buy heavily into Illinois Central and, soon after, join his friend Stuyvesant on the board. Together, they began going after more railroad routes. In the process, Harriman found himself in rivalry with the legendary J. P. Morgan for control of an obscure Iowa railroad, the Dubuque-and-Southern.

Morgan and a group of investors seemed to hold enough shares of stock to decide the fate of Dubuque-and-Southern at a forthcoming annual meeting by determining who would serve on the railroad’s board of directors, but Harriman flooded the meeting with enough proxies from small investors to win election of a slate of directors of his own choosing. The board then approved sale of the railroad to Harriman’s Illinois Central. Morgan threatened court action but finally acquiesced to the “little man” and sold his pool of shares at a price set by Harriman.

Harriman would not long remain a “little man” in terms of business muscle and wealth. By the beginning of the twentieth century, he controlled the Union Pacific and Southern Pacific railroads and stood among equals at the highest level of corporate power. This was confirmed when he and Morgan set aside their rivalry and joined with railroad tycoon James J. Hill in a transaction in 1901 to merge the Northern Pacific, Great Northern, and Chicago-Burlington-Quincy railroads. This merger sparked yet another high-profile contest, this time with President Theodore Roosevelt. Through the Department of Justice, the trust-busting president sought to dissolve the railroad merger on the grounds that Harriman, Morgan, and Hill would have a grip on national railroading verging on a monopoly. In a five-to-four vote by the Supreme Court in 1904, the president prevailed. But business was just business and did not preclude Harriman from raising $250,000, including a personal contribution of $50,000, in support of Roosevelt’s 1904 presidential campaign.

Harriman, Roosevelt, and Morgan tripped over each other in a robust, competitive nation just beginning to feel its industrial might, but the natural treasure-trove along the New Jersey Palisades and in the New York Highlands brought them to an informal point of brotherhood.

The scenic values in the highlands attracted Morgan to acquire and maintain a grand weekend home in Highland Falls, just downriver from West Point. He and John D. Rockefeller, George Perkins, Dr. Partridge, and so many others were sharing the view and being influenced by one of the most superlative river ecosystems in America. Harriman’s view was somewhat different. In 1885, he purchased land from iron-maker Peter Parrott, made famous during the Civil War for manufacturing the “Parrott Rifle,” a cannon of improved range and accuracy that gave strategic advantage to Union troops. The Parrott iron mines and furnaces were in Sterling Forest, a splendid natural segment of the New York Highlands.

After the Civil War, when abundant iron ore was discovered in Minnesota and prices fell, Parrott’s business collapsed. At a distress auction, Parrott placed his entire 7,863-acre land holding on the block, hoping that parcels would be divided among competing speculators, especially those interested in timber rights, to provide maximum financial return for him. Harriman saw a different opportunity. He wanted to prevent the land from being subdivided and timbered and went for the entire acreage. His bid of $52,500 prevailed. In succeeding years, Harriman would add another 20,000 acres to the Parrott purchase by acquiring some forty surrounding properties. He named his estate “Arden” in honor of Parrott’s wife. The Arden view was to the west over rolling woodland hills, the Hudson River miles away out of sight to the east, but all within an ecosystem that Dr. Partridge had proposed as a national park.

Harriman’s conservation instincts were confirmed in 1898 when his doctor recommended a family vacation as treatment for business fatigue. Harriman decided to make the vacation into a scientific expedition to Alaska. When the day arrived in May 1899 for departure of the chartered ship George W. Elder from Seattle, Washington, Harriman welcomed aboard a traveling party of 126 people, including the eminent naturalists John Burroughs and John Muir. This was his idea of a restful excursion. The 9,000-mile voyage would take two months, reaching the coast of Siberia. Wild animal, bird, plant, and aquatic specimens were “collected” at the many shoreline stops along the way, as well as museum-quality art objects and artifacts found at the villages and campsites of indigenous peoples.

Muir had one later opportunity to visit Harriman, this time at the railroader’s wilderness lodge at Pelican Bay, Klamath Lake, Oregon. Harriman had promised to “show you how to write a book” and made available a stenographer who spent many summer days recording Muir’s ideas and musings. “To him I owe some of the most precious moments of my life,” Muir said of his host. In subsequent writings, Muir followed this thought:

Of all the great builders—the famous doers of things in this busy world—none that I know of more ably and manfully did his appointed work than my friend Edward Henry Harriman. He was always ready and able. The greater his burdens, the more formidable the obstacles looming ahead of him, the greater was his enjoyment. He fairly reveled in heavy dynamical work and went about it naturally and unweariedly like glaciers mining landscapes, cutting canyons through ridges, carrying off hills, laying rails and bridges over lakes and rivers, mountains, and plains, making the nation’s ways straight and smooth and safe, bringing everybody nearer to one another. He seemed to regard the whole continent as his farm and all the people as partners, stirring millions of workers into useful action, plowing, sowing, irrigating, mining, building cities and factories, farms and home.

In general appearance he was said to be under-sized, but though I knew him well I never noticed anything either short or tall in his stature. His head made the rest of his body all but invisible. His magnificent brow, high and broad and finely finished, oftentimes called to mind well-known portraits of Napoleon. Every feature of his countenance manifested power, especially his wonderful eyes, deep and frank yet piercing, inspiring confidence, though likely at first sight to keep people at a distance.

In the first decade of the twentieth century, George Perkins and his commission colleagues had not yet joined in active alliance with Harriman, although they surely were aware of his immense landholding in the New York Highlands. They were struggling to close the final land deals in New Jersey and were on the defensive in New York for not having rid Hook Mountain of quarry dynamite blasts. J. DuPratt White wrote to one critic that “the reason the commission has not acquired the Hook Mountain, and the only reason, is that the commission is without funds—I can assure you that exhaustive efforts have been made to accomplish this end in every way that the ingenuity of the commission has been able to devise.”

George Perkins saw opportunity in 1909 to raise the profile of the commission by joining in the 300th anniversary of Henry Hudson’s “discovery” of the river named in his honor. At the same convenient time, the centennial of Robert Fulton’s development of the steamship would be acclaimed—from sail to steam, so to speak. Perkins promoted the idea that the Hudson-Fulton celebration also should be combined with formal dedication of the Palisades Interstate Park in New Jersey, contending that protection of the scenery as it appeared during the voyage of the Half Moon, and for river travelers since, was a fitting tribute. From his upriver post, Dr. Partridge also wanted to participate to advance his national park idea. He succeeded in winning appointment to a Tercentenary subcommittee charged with studying the idea, but the subcommittee never met. Partridge, probably the most eager member of the subcommittee, was able to gain only a bit of attention in Albany and none in the U.S. Congress for his national park notion. The idea sputtered and flamed out.

Perkins won better results, especially fueled by a $20,000 donation that he and his employer, J. P. Morgan, made to help fund the celebration. Perkins was appointed to the Tercentenary Commission “so that there might be the fullest possible interchange of views between the two bodies, Interstate Commission and Tercentenary Commission.” Even so, when the official announcement of the pending celebration appeared in newspapers on August 31, 1909, no mention was made that the commission dedication would be included. Perkins strongly objected. The chairman of the commission, General Stewart L. Woodford, had words with an army colonel who had arranged for the news release. More than 500,000 copies of an amended announcement were quickly distributed.

On September 27, 1909, a huge crowd gathered on the shoreline at the base of the Palisades cliffs to witness the dedication of the Palisades Interstate Park. Thirty-five musicians and many dignitaries were transported to the site on the Waturus, Perkins’s private yacht. Governors Charles Evans Hughes of New York and J. Franklin Fort of New Jersey were in attendance. So, too, was Elizabeth Demarest, the official representative of the New Jersey Federation of Women’s Clubs. The club members thought that completion of their memorial in conjunction with the dedication would be ideal. The commission’s beleaguered messenger, White, responded that “everyone is overwhelmed with the work in connection with the celebration in general” and that the long-sought women’s memorial must await another time. A group representing the Iroquois Nation performed a ceremonial dance, perhaps reminding some in attendance that not all had benefitted equally from voyages by Europeans.

Perkins announced to those assembled that a “Member of the Tercentenary Commission,” meaning himself, had donated $12,000 to the commission, supplemented by a gift of land valued at $16,000 from Cleveland H. Dodge. He said that the commission privately raised a total of $284,000 in gifts of land and money, particularly crediting J. P. Morgan, Cleveland Dodge, Mrs. Lydia G. Lawrence, and Mr. and Mrs. Hamilton Twombly. Perkins noted that in the intervening nine years since the two states had provided the first $15,000 of appropriated funds to begin land purchases, an additional $20,000 had been received from New York and $17,500 from New Jersey.

He confirmed that almost all the 175 parcels, including twenty-one houses, needed to guard the integrity of the Palisades cliff face now were in commission ownership. “Here, within sight of our great, throbbing city is a little world of almost virgin nature which has been rescued for the people and now stands as a permanent monument to the discovery of the river by Henry Hudson,” said Perkins. His statement was confirmed years later by Nancy Slowik in A Nature’s Guide to the Southern Palisades. Her guide lists 11 species of amphibians, 12 of reptiles, 50 of butterflies, 29 of mammals, 232 of birds, 60 of trees, shrubs, and vines, and 51 of wildflowers, ferns, and grasses.

Perkins credited Elizabeth Vermilye, Cecelia Gaines Holland, Franklin W. Hopkins, William A. Linn, S. Wood McClave, Andrew H. Green, Frederick W. Devoe, Frederick S. Lamb, Abraham G. Mills, and Edward Payson Cone for assertive work in the citizen crusade to save the cliffs. “Man can do no more than preserve its natural grandeur and make the park accessible to one and all.” The Navy warship Gloucester boomed a cannon salute from the river that echoed off the rocky wounds of silent quarries. The musicians struck up a lively rendering of the Star-Spangled Banner.

One person not mentioned at the celebration was Charles E. Howard, superintendent of New York Prisons, who was to become a highly unlikely and unwilling ally of the commission. Howard had been looking for a prison site and concluded that undeveloped wildland at Bear Mountain, just downriver from West Point in the Hudson River narrows, would do just fine. The state needed stone for public highway construction. While the commission was being applauded for the quarry demise in New Jersey and criticized for not doing enough at Hook Mountain, Howard was off on a different track, convincing the New York Prison Commission that there was plenty of stone for road-fill at Bear Mountain that could be mined by prison labor.

In 1908, just a year before the Hudson-Fulton celebration, the prison commission approved purchase of 700 acres at Bear Mountain from C. E. Lambert. Howard immediately set convicts to work clearing land and building a log stockade. The stockade would take on the appearance of a Wild West fort.

Bear Mountain Prison stockade (PIPC Archives)

The work force came from notorious Sing Sing Prison, and so many convicts took the opportunity to escape that nearby hamlets were said to be in a “state of terror.” The intent was that the stockade would house 1,500 to 2,000 inmates, who, except on Sundays, would be marched up the slopes of Bear Mountain to mine rock, prybars, pickaxes, and shovels in hand. The commission was startled and anxious about this unexpected exploitive curveball. At the conclusion of the ceremony at Cornwallis Headquarters, Perkins hosted New York governor Hughes aboard the Waturus to express urgent concern.

Upriver, Dr. Partridge, checkmated on his national park idea, turned his considerable clout to forest protection. Partridge’s new cause was prompted by Gifford Pinchot, former dean of the State School of Forestry at Cornell University, founder of the Society of American Foresters, and chief of the U.S. Forest Service in the Theodore Roosevelt Administration. Pinchot had sent out the alarming message that all mature trees in the United States would be cut down within twenty-five years if the present pace of out-of-control logging were allowed to continue. Added to this threat, deadly chestnut blight (Cryphonectria parasitica) had reached the New York Highlands. The grand and ancient chestnut trees had no defense. Most of the iron mines in the highlands had been shut down, but the Forest-of-Deane mine still was in operation, consuming large quantities of wood for its furnaces. Brick manufacturing also was common, the red-hot kilns fueled each year by thousands of cords of hardwood.

In response to the forest threat, on May 22, 1909, the New York legislature approved the Highlands of the Hudson Preservation Act. The act declared that “perpetuation and improvement of forest growth is declared to be in the public interest.” To secure forest protection, the act called for designation of a resident forester whose daunting tasks would be to develop regulatory principles for public and private lands, see to construction of a highway to provide access, and prevent forest fires. Partridge provided data to help along the process, pointing out that private holdings in the highlands, excluding the Harriman estate, ranged from fifty to 5,000 acres, and that 500- to 1,000-acre plots were “common.” The average per-acre cost was between $25 and $50. Property taxes ranged from $4 to $8 per acre.

The good news was that careful forest practices already were being implemented at the 16,000-acre U.S. Military Academy, West Point, and on the 27,000-acre Harriman estate. But the very bad news was that E. H. Harriman was extremely ill with cancer. The man whom John Muir described as going about work like “glaciers mining landscapes” was doomed. He died in September 1909 at age sixty-one, leaving his $70 million estate to his wife, Mary.

Before his death, Harriman confided in Mary a strong interest in the park concept proposed by Dr. Partridge and made this interest known to Governor Hughes. The prison project at Bear Mountain, just beyond the eastern boundary of the Harriman estate, caused his interest to rise to a level of resolve that would pull the commission into park stewardship at a level not imagined. Harriman wanted to make an offer to the state of New York that could not be refused: if the prison board would move the prison somewhere else, Harriman would donate thousands of acres to the commission and donate $1 million to help with stewardship costs. Mary Harriman was determined to see his wishes fulfilled.

George Perkins scheduled a meeting of the commission on December 16, 1909, accompanied by the minimalist message that he “particularly asks that every member of the commission will endeavor to be present, as matters of great importance to the commission will be brought before the meeting.”

The minutes of the meeting include reference to a letter from Elizabeth Vermilye urging acquisition of a property referred to as “Clinton Point,” but the commission had declined because of lack of funds. A bill for $294.17 was submitted for approval to cover the costs of purchasing and mailing 357 copies of the book The Palisades of the Hudson, by Arthur C. Mack, to every member of the New Jersey legislature. Perkins submitted personal receipts for $45.00, representing expenses for a recent trip to Albany, then added that he would consider the expenses a contribution to the commission.

Then, the bland minutes confirm that “Mr. Perkins announced that Mrs. E. H. Harriman had signified her willingness to deed 10,000 acres at Arden, New York, to the commission, together with $1,000,000 in cash, provided others would contribute to the extent of $1,500,000, and all of the contributions to be conditioned upon the State of New York contributing an equal amount of $2,500,000.”

Perkins added that he had completed negotiations “for a plan which would permit extension of this commission to West Point.” The plan also would “permit construction of the boulevard and the acquisition of such lands between the present jurisdiction and the proposed jurisdiction as might be considered necessary.” He then added that anonymous private pledges, already in hand, had reached the $1 million mark. The minutes said nothing about the magnitude of such a breathtaking leap in purpose and obligation. Perhaps the commissioners, most of whom were accustomed to big business deals, were completely comfortable with this giant leap in purpose and responsibility.

In a follow-up meeting on December 23, the details of the Harriman proposal were spelled out:

1. That in order that the Palisades Park Commission may carry out the proposed plan and receive and hold the land and money offered the State by Mrs. Harriman, its jurisdiction shall be extended to the northward along the west bank of the Hudson river to Newburgh, and to the westward as far as and to include the Ramapo mountains, giving the Commission the same powers granted to it at the time it was created and at the time its jurisdiction was extended in 1906, including the right to condemn land for roadway and park purposes.

2. That the State of New York appropriate $2,500,000 to the use of the Commission for the acquiring of land and the building of roads and general park purposes.

3. That the State discontinue the work on the new State prison located in Rockland county, and relocate the prison where, in the judgment of the Palisades Park Commission, it will not interfere with the plans and purposes of the Commission.

4. That in addition to the aforesaid appropriation from the State, a further sum of $2,500,000, including Mrs. Harriman’s pledge of a million dollars, be secured on or before January 1, 1910.

5. That in addition to the above $5,000,000, the State of New Jersey appropriate such an amount as the Palisades Park Commission shall deem to be its fair share.

On motion, the meeting was adjourned. Perkins and White already had scheduled a meeting the following day with Governor Hughes. They presented an imposing list: fundraising pledges that exceeded the Harriman challenge by $150,000.

| John D. Rockefeller | $500,000 |

| J. Pierpont Morgan | $500,000 |

| Margaret Olivia Sage | $50,000 |

| William K. Vanderbilt | $50,000 |

| George F. Baker | $50,000 |

| James Stillman | $50,000 |

| John D. Archbold | $50,000 |

| William Rockefeller | $50,000 |

| Frank A. Munsey | $50,000 |

| Henry Phipps | $50,000 |

| E. T. Stotesbury | $50,000 |

| E. H. Gray | $50,000 |

| George W. Perkins | $50,000 |

| Cleveland H. Dodge & James McLean | $25,000 |

| Helen Miller Gould | $25,000 |

| Eileen F. & Arthur Curtiss James | $25,000 |

| V. Everitt Macy | $25,000 |

Perkins had been joined by John D. Rockefeller to tap into high levels of New York society through personal contact to achieve the fundraising goal. Among those contacted was Andrew Carnegie, who declined, explaining to Rockefeller that he was raising $5.5 million for libraries.

On January 6, 1910, Governor Hughes delivered a message to the legislature urging positive response to the proffered Harriman gift, but the governor hedged his bet. Instead of seeking an outright appropriation, Hughes used as excuses lack of tax revenue and other state financial obligations and, instead, recommended that a $2.5 million bond be issued for the purpose. The caveat was that a bond would have to be approved by the entire New York electorate. This was a novel political maneuver. Never before had New York voters been asked to approve borrowing by the state in the form of a bond to protect nature’s handiwork. Bonds had been used to fund construction projects, not prevent them. But the governor was willing, the legislature was supportive, the heavily influential names of Rockefeller, Harriman, Morgan, and Perkins were associated, and the scenic magnificence of the Hudson River Narrows and the New York Highlands was at stake.

On October 29, 1910, an eighteen-year-old nervous Yale college student named William Averell Harriman, acting on behalf of his mother and family and speaking publicly for the first time, handed a deed for 10,000 acres to George Perkins, along with three checks totaling $1 million. In ceremonial coordination, the 700-acre prison tract was transferred from the state of New York to the commission. Mrs. J. Pierpont Morgan and her daughter, Mrs. Herbert Satterlee, sat with Mrs. Harriman to witness the ceremony. Mr. and Mrs. Henry Phipps and Mrs. Perkins sat nearby.

Among other attendees were Dr. Partridge and ex-Governor Odell. Partridge’s Forest Preservation Act had been rescinded as part of the political strategy to win approval of the bond issue, but the doctor was happy. His vision of a highlands park was being fulfilled, and, unknown to him at the time, he soon would be appointed to the interstate commission and would serve for fourteen years, until 1929. Odell, who had first supported the commission as Theodore Roosevelt’s successor but then opposed its expansion when he became a lobbyist for quarry operators, must have been amazed by the sweep of purpose and financial clout being conferred on the commission that October day. Commission authority now extended from Fort Lee, New Jersey, for forty-five miles upriver to West Point, New York.

Ironically, the opening speaker at the ceremony was William J. McKay, chairman of the New York Prison Commission. He alluded to a retreat of Hessian soldiers from Bear Mountain during the Revolutionary War, adding that the prison commission also welcomed the opportunity to retreat. (McKay had his facts backward; an overwhelming British and Hessian force attacked forts Clinton and Montgomery at Bear Mountain in 1777, forcing the retreat of 600 Continental Army troops.) But the prison commission retreat was not without a price tag. The commission found itself purchasing prison assets including a railroad bridge, fifty thousand bricks, the guard barracks, stockade, and warden’s quarters, furniture, plumbing fixtures, and seventy railroad rails, each thirty feet long, weighing a total of 42 thousand pounds. The prison commission provided without charge a flagpole, barn, old sheds, and one set of ice tools.

The next speaker was J. DuPratt White, who, on acceptance of the 700-acre prison tract, said, “I shall avail myself of this, my first opportunity to speak of the work of George Perkins as Commissioner. His time, his thought, his advice, and his energy have been unstintedly devoted toward the accomplishment of what has been done.” White then read letters from governors Hughes and Fort. Governor Hughes referred to a slight technical detail; the $2.5 million bond was not yet in hand, but the governor was confident that New York voters would approve of it in the November election, a prediction that proved to be accurate only because the vote count in New York City and nearby counties outnumbered the universally negative upstate response. Governor Fort confirmed in his letter that a $500,000 New Jersey appropriation to the commission had been made to fund construction of a road along the base of the Palisades cliffs.

After the governors’ letters were read, Sargent H. C. Lieb, in command of a West Point field cannon, ordered nineteen rapid-fire salutes to the ear-splitting delight of those assembled. Then it was young Averell Harriman’s turn:

In accordance with the long-established plan of my father to give to the State of New York, for the use of the people, a portion of the Arden estate, and acting on behalf of my mother, I now present to the Commissioners of the Palisades Park the land comprising the gift. I also hand you my mother’s contribution to the expense of future development of the Harriman Park. It is her hope and mine that through all the years to come the health and happiness of future generations will be advanced by these gifts.

On acceptance, George Perkins predicted that the day marked “the beginning of what certainly will become one of the largest, most beautiful, and practical recreation grounds in all the world.”

Bear Mountain/Harriman State Parks (PIPC Archives)

A follow-up report in the New York Times stated:

Nature itself had provided the setting. On three sides of the little plateau where the ceremony was held were the hills which form the rugged group clustering around Bear Mountain, just across the Hudson towered Anthony’s Nose, jutting out into the river, and over the foothills shone the top of Storm King, the highest and most rugged of the mountains. All were colored red and gold by the Autumn foliage, a natural picture on which the group of men and women on the plateau gazed in admiration during the hour or more of the ceremony.

Mr. Kunz of the American Scenic and Historic Preservation Society collected the brass casings of five shells fired from the West Point field cannon, polished them, and sent them to Mary Harriman to be used as flower vases.