Читать книгу Palisades - Robert O. Binnewies - Страница 21

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

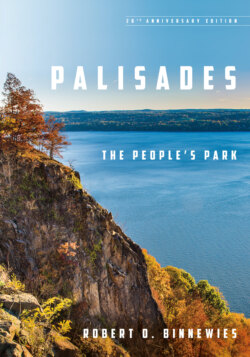

Welch

ОглавлениеApril 15, 1910

Mr. Frank E. Lutz

Assistant Curator

American Museum of Natural History

Dear Sir:

Replying to your favor of the 14th instant, I beg to advise you that the Commissioners gladly extend permission to you to collect insects in the Interstate Park.

Yours very truly,

J. DuPratt White

SCIENTIFIC STUDY OF moths, beetles, ants, mosquitoes, ticks, fireflies, crickets, and insects in general seems so esoteric to most people that it usually wins nothing more than amused and fleeting curiosity; an eccentric person in a pith helmet, romping through fields with a butterfly net is the popular image of the entomologist. Dr. Frank Lutz very likely did use a butterfly net, and his work with the American Museum of Natural History established him as a major presence in the nation’s scientific and educational community. Before his career ended in 1943, Lutz developed a museum collection of more than two million specimens of insects, one of the great baseline scientific collections in the world.

Lutz was drawn to the open space being protected by the commission for its potential as an outdoor laboratory. Where others saw recreational opportunity, he saw in the highlands a rich source of scientific knowledge. Like almost all environmental scientists, Lutz needed access to protected lands that were rent-free, or nearly so. Budgets for his type of work ranged from meager to nonexistent. In addition to cost considerations, he was lured to the commission parklands because of proximity to the Museum of Natural History in New York City. Lutz could develop baseline data knowing that lands on which he roamed with his butterfly net could be revisited time and again, secure from the risk of urban or suburban burial.

He enjoyed delivering messages in a manner that had staying power. Once, he tried to make a wager with the director of the Museum of Natural History that he could find more than 500 species of insects in his 75-by-100-foot backyard in Ramsey, New Jersey. When the director declined the wager, Lutz countered by proposing that his salary be raised by $10 per year for every species above 500 that he could find. Still the director declined, but Lutz made the count anyway. He documented 1,402 insect species.

In 1925, through a grant provided by W. Averell Harriman, Lutz was able to establish the Station for the Study of Insects on a forty-acre commission-owned plot in the highlands. The station became an outdoor classroom, allowing young students to work and stay in the camplike setting during summer months. One of these students was ten-year-old David Rockefeller, youngest son of John D. Rockefeller Jr. Insects are not for everyone, but David was so fascinated that he became an expert in beetles. Of his later travels as banker, statesman, and business leader, Rockefeller said, “I can go anywhere in the world and will know with certainty about one thing, beetles.” He personally assembled a spectacular, comprehensive, and scientifically meaningful collection of more than 150,000 beetle specimens now available for study at the Harvard University Museum of Natural History.

To encourage his students, Lutz developed a trail around the station and posted small signs to identify interesting plants, insect haunts, and other natural features. In so doing, he created the first nature trail in the United States. At the beginning of the trail, the first sign read,

The spirit of the training trail: a friend somewhat versed in natural history is taking a walk with you and calling your attention to interesting things.

In 1926 Lutz expanded his educational and scientific interests to Bear Mountain by establishing the Trailside Museum in cooperation with the American Museum of Natural History. The Trailside Museum and Wildlife Center remains a significant, highly popular asset for park visitors.

By bringing the prestige and integrity of the Museum of Natural History to the woods, meadows, marshes, lakes, and streams of the highlands, Lutz confirmed the scientific and educational benefits of parks. He recognized the potential of these lands to engage the intellect as well as the senses. Research and educational activities aimed at a better understanding of the environment, so widespread in parks throughout the nation today, can be traced to a man with a butterfly net.

George Perkins likely was aware of Lutz’s initiative to bring practical science under the commission’s banner, but he had other concerns on his mind. At the end of 1910 Perkins retired from J. P. Morgan & Company. He had worked hard, won significant business victories for Morgan & Company, and gained great wealth. Perkins judged that the time was right to enjoy the independence that wealth provided. He freed himself from corporate structure to pursue personal interests, most especially the Palisades project.

The Harriman gift, too, was a motivating factor. Perkins had been continually at the helm of the commission but had not been immersed in the many day-to-day details that were rapidly transforming its assumptions and needs. In a memorandum that accompanied his retirement announcement, Perkins explained, “I have long felt that it is not wise to leave all our public affairs to the politicians, and that business men of sufficient leisure and means should for patriotic reasons give their attention to great public problems.” His retirement from active business life also reflected growing stress in his relationship with J. P. Morgan. Perkins’s biographer, John A. Garraty, wrote that Morgan’s “increased irascibility and distrust” had found its way to Perkins himself. The break was stormy but not irreparable. Although a professional coolness thereafter existed between the two men, Morgan continued to respond to commission fundraising pleas, and Perkins always used the quaint phrase “dear Senior” in a respectful and affectionate manner when referring to the elder financier, who had catapulted him to the top of the business world.

Perkins’s more focused attention on commission matters came none too soon. The commissioners were under criticism for not responding to the demand that Henry Hudson Drive, envisioned for the base of the Palisades in New Jersey, be extended northward along the river shore, perhaps all the way to Bear Mountain, thirty miles north of the New Jersey–New York border. J. DuPratt White again served as the lightning rod. In a lengthy letter to the editor that appeared in the New York Times, White defended the commission and explained the practical difficulties of the road project, adding that “as is usually the case with writers of letters to newspapers for the purpose of correcting supposed public wrongs, your said correspondents are hopelessly ignorant of their subject matter. They show no knowledge whatsoever of the laws creating or governing the great Interstate Park, of the plans of this Commission, or of the topography or geography of the region.”

Controversy swirled around the question of roads. Perkins was accused of bowing to the wishes of Mrs. Lydia G. Lawrence by refusing to condemn her property on the border of the two states to make way for the road project. A New Jersey assemblyman wrongly denounced commissioners William A. Linn and Abram De Ronde, both appointed in 1900, for cashing in on commission projects through the National Bank of Hackensack and the Palisades Title and Guarantee Company of Englewood, New Jersey, controlled, respectively, by Linn and De Ronde.

Despite these criticisms, on March 11, 1911, a headline in the Rockland Journal News proclaimed, “COMMISSION BUYS THE HOOK.”

What a few months ago seemed to many like an impossibility, or a difficult proposition at the least, has been accomplished really in a few weeks by the Palisades Park Commission.

Five years after the commission’s authority was extended north of the New York/New Jersey state line to include Hook Mountain, the Barber Asphalt Company sold its subsidiary, the Manhattan Trap Rock Company, to the commission for $415,000, including a large concrete powerhouse at Nyack Beach. Attorney Irving Hopper of Nyack, New York, assisted in settling the details of the purchase. Only two quarries, the Rockland Lake and Clinton Point Trap Rock companies, remained in operation. The hard-fought contest with the quarry operators was coming to an end.

The heightened profile and success of the commission led landowners to approach the commission in the hope of selling their properties at inflated values. Proposals were advanced, only to collide with the time-tested business and legal skills of the commissioners. Publicity caused by the Harriman gifts of land and money and the associated increase in private and government funding for the commission did not change the basic style of Perkins, White, and their colleagues. Each dollar was squeezed for maximum benefit. Those looking for quick windfall profits, including Addison Johnson, who owned 500 acres at Bear Mountain, were firmly discouraged. Johnson proposed to sell his land to the commission for $100 per acre, total price $50,000. The commissioners learned that Johnson had purchased the property two years earlier for $7,500 and refused further contact with him for several months. When Perkins did reopen the negotiation, he offered Johnson $10,000 and gave the owner two weeks to accept. Johnson accepted.

Steven Rowe Bradley of Nyack, New York, made a much more attractive offer. Bradley proposed to donate 212 acres on South Mountain, to be designated “Rockland Park.” Bradley was a community leader who was instrumental in forming the Nyack National Bank in 1878, the Nyack Library in 1879, and the Nyack Hospital in 1895. At their May 1, 1911, meeting, the commissioners accepted Bradley’s generous offer to begin the creation of a park on South Mountain. But the donor was in ill health. Before the transaction could be completed, he passed away at the age of seventy-five. His children immediately took up the cause, and title to the Bradley property was transferred to the commission in October.

In a foresighted letter to the commissioners, the Bradley heirs expressed their collective expectation that the land “shall be deeded for a natural park, to be held for the benefit and enjoyment of the public at large, open at all times for their use—to secure the perpetuation of the birds, animals, plants, trees and other natural features—and to restrict and govern the admission of motor vehicles.” On behalf of their father, and so early in the century, S. R. Bradley, Mary T. Bradley, Augusta B. Chapman, and William C. Bradley were recommending guidelines for park stewardship that would become the focus of constant debate between preservation advocates and proponents for the exploitation of parks. Their concern about “motor vehicles,” at a time when horse carriages still outnumbered automobiles, is reflected in today’s many hotly contested park debates. Popular parks suffer traffic gridlock; off-road vehicles scar fragile desert habitat; snowmobiles shatter winter quiet. (One example: in 1980, a plan was approved with strong public support that called for restricted automobile access to Yosemite Valley, California. Since then, because of commercial pressure, traffic congestion has increased.)

The Bradley heirs clearly expressed their hope for the perpetuation of natural features but may not have known about incoming flying bullets. A state rifle range existed on the summit of South Mountain adjacent to the Bradley property. Samuel Broadbent, president of the Board of Health, Village of Grand View-on-Hudson, New York, wrote to Perkins to urge the commission to acquire the range. J. DuPratt White responded:

In the form of affidavits, I suggest that you gather as much evidence as you can of actual trespass of bullets upon the properties of residents in the villages. It is common talk that bullets have entered houses through the walls or roofs and the windows, and that bullets have also been seen to strike the ground within the limits of the several villages. These circumstances, it seems to me, should be run down and proper evidence embodied in affidavits before any Legislative committee is asked to pass upon a bill.

In other words, the commission was interested and willing to help if the residents of the village could provide convincing proof that bullet holes in their houses had come from the rifle range. With facts in hand, and by an act of the legislature two years later, the 500-acre rifle range was transferred to the commission.

South Mountain is a high ridge above Piermont, New York, offering a sweeping, forty-mile view of the Hudson River. The ridge accommodates Tweed Boulevard, named for the infamous “Boss” William M. Tweed, master of New York City machine politics. Tweed sponsored a road connection from Hoboken, New Jersey, to Nyack, New York, and the narrow road on the summit of the ridge is testimony to a powerful politician who could make things happen. Tweed ultimately fell from his commanding position in the rough-and-tumble of his political world when he was convicted of fraud and sent “up the river” to Sing Sing Prison to spend his last days behind bars. But Tweed Boulevard, providing access to land donated by the Bradley heirs and the adjacent commission-acquired rifle range (present-day Blauvelt State Park), remains a fixture on the ridge summit.

Almost in concert with the Bradley gift, Dr. James Douglas of New York City offered to donate to the commission several tracts of land atop the New Jersey Palisades. This proposal, too, was accepted, drawing the commissioners ever closer to involvement with the rolling lands and elegant estates that capped part of the cliffs. These properties had escaped the attention of the commission during its battle with the quarry operators, but the spectacular river views from the summit lands, their inherent and exquisite wildness, and the need to improve access to increasingly popular park holdings were proving to be irresistible to the commissioners.

Acquiring manor-like properties was running parallel with growing commission interest in the idea of a grand boulevard that would allow for leisure motor travel from New York City to Bear Mountain. Charles W. Leavitt Jr., chief consulting engineer for the commission, recommended that the services of consulting engineer Alfred Nobel (famed as the inventor of dynamite and later to endow the Nobel Prize) be retained to study the boulevard concept. The obvious challenge was that no bridge existed that connected the city with the Palisades. Automobiles would arrive via ferryboat. Among the options suggested by Leavitt and Nobel was to drill an ascending road tunnel through the cliff face from the base of the Carpenter brothers’ old quarry site to the summit of the Palisades. The idea was not discarded out of hand. At the invitation of Perkins, the commissioners would discuss boulevard options at their next meeting to be held aboard his yacht, Thendara. A meeting on the yacht was timely because another concern much on the minds of the commissioners was the obvious and increasing pollution of the Hudson River.

Raw sewage was being dumped into the river from every village and municipality along its shores. Ships and boats plying the river commonly jettisoned whatever they wished. Driftwood was a menace to small craft and was clogging the New York Harbor shoreline. The river, popular with swimmers, canoeists, sailors, yacht owners, and anglers, was a handy, untreated Hudson River Valley disposal system. The commission began petitioning governors John A. Dix of New York and newly elected Wood-row Wilson of New Jersey to clean up the river.

Problems were mounting, and one, in particular, persisted. White responded to a resolution critical of the commission that had been approved at the 1911 annual convention of the New Jersey Federation of Women’s Clubs. White wrote in a letter to Mrs. Joseph M. Middleton:

The resolution is a protest against the present condition of the park, and a demand by the Federation that the original idea of the Federation be given consideration, but I do not know what the Federation’s original idea was. The resolution further provides that measures shall be adopted to make the tract a true park, with a fitting memorial approved by the women of New Jersey. Will you kindly inform me whether or not the Federation is under the impression that this Commission has ever undertaken to expend any money on said Memorial Park?

After more than a decade, commission institutional memory and White’s personal memory apparently had faded, and the Federation of New Jersey Women’s Clubs, still without its monument, would have to wait still longer.

Another vexing challenge was about to surface. In 1912, people who wished to establish a summer camp to be supervised by the National League of Urban Conditions Among Negroes contacted the commission. The commissioners promptly approved the camp in concept, finding logic and appeal in the idea that parklands could benefit any child, regardless of race. But they were to confront the racial attitudes of the early twentieth century and would struggle to open the park door to people of all races.

Other matters large and small came to the table for commission decisions. In one meeting, the commissioners focused their discussion on choices for the width of a steep road planned from the Palisades summit at Englewood, New Jersey, down to the shoreline below. Apparently, the idea of tunneling through the old quarry site had been discarded. Facing the commissioners and their chief consulting engineer was a precipitous drop down the cliff face that would be daunting for any road builder. The middle-aged and elderly bankers, lawyers, and businessmen of the commission scheduled a field visit to the site, where they scrambled up and down the proposed route, huffing and puffing, to determine the road width needed to allow automobiles to get through the hairpin turns.

In November 1912, Perkins wrote to John D. Rockefeller Jr. to report the following developments: the quarries at Hook Mountain were being acquired either through willing-seller transactions or by condemnation; the Henry Hudson Drive in New Jersey was under construction; docks had been built along the river to improve public access, including a very large dock at Bear Mountain; the Bear Mountain site itself would be opened to the public the following year; water supplies, sanitation facilities, and picnic and camping areas were being installed to meet increasing visitor demands; and forests were being cleared of deadwood. Perkins concluded the letter by reminding Rockefeller Jr. of his financial pledge to the commission: “The amount of your subscription is $500,000; you have paid $200,000, leaving a balance of $300,000. The Commission will very much appreciate receiving a check for this amount on or before December first of this year.” Rockefeller willingly complied.

While adjusting to his retirement from Morgan & Company and grappling with the increasingly complex commission agenda, Perkins took on another demanding extracurricular task, as described by Garraty:

It is the evening of June 20, 1912; the scene, a large room in the Congress Hotel in Chicago. About twenty men are present. Perhaps a dozen of them are seated around a large table. Others sprawl wearily in armchairs or lean against walls. One, a solid, determined-looking fellow with thick glasses and a bristling mustache, paces firmly back and forth in silence, like a caged grizzly. He is Theodore Roosevelt, and these are his closest political advisers. All of them are angry, very angry.

In a nearby auditorium, the Republican National Convention is moving with the ponderous certainty of a steamroller toward the nomination of well-fed William Howard Taft for a second term as President of the United States. All of the men in the hotel room believe that this nomination rightfully belongs to Roosevelt.

It is growing late, and everyone is weary. Conversation lags. But gradually attention is centered on two men who have withdrawn to a corner. They are talking excitedly in rapid whispers. One is the publisher Frank Munsey; the other, George W. Perkins. Neither has had much political experience, but both are very rich and very fond of Theodore Roosevelt. Now everyone senses their subject and realizes its importance. All eyes are focused in their direction. Suddenly the two millionaires reach a decision. They straighten up and stride across the room to Roosevelt. Each places a hand on one of his shoulders. “Colonel” they say simply, “we will see you through.” Thus, the Progressive party, “Bull Moose” some call it, is born.

Munsey’s involvement in the Progressive Party was brief, but Perkins made a commitment and intended to do exactly as he said, see it through. He became campaign manager for Roosevelt’s bid for another presidential term. Perkins’s ideals and philanthropic activities were suggested to reporters in those rare moments when he nudged open the door to his personal thoughts. “Shall I go on and pile up a few more millions on top of those I have already acquired and make a big money pile the monument to my memory? A man should ask himself, what is this all about? Where is my work going to lead me?” By his actions, Perkins, at age fifty, was answering these questions for himself.

He and Roosevelt seemed the odd couple, Roosevelt the trustbuster joining Perkins the monopolist. But there was no contradiction in Perkins’s’ alignment with the Progressive movement. The interstate commission had formed a Roosevelt-Perkins bond, and both the commission and this new venture into politics provided avenues that promised social benefits for working men and women, values long championed by Perkins. From the very beginning of his business career, he had maintained a strong interest in socially beneficial government policies and regulation. His involvement with the Progressive Party was an extension of this long-held interest.

The candidates in the 1912 election were President Taft, former President Roosevelt, and New Jersey governor Woodrow Wilson. The popular Wilson prevailed in the election. Roosevelt carried six states and finished in second place. Even after the loss, Perkins remained involved with reform politics in the Progressive and Republican Parties, although his duties as president of the commission were an increasingly central focus of his public work.

That work was not going well. Within the commission, controversy developed over the performance of chief consulting engineer Leavitt. The New Jersey commissioners sought Leavitt’s removal from direct supervision of the Englewood approach-road project. As a result, Leavitt remained in charge of general engineering work for the commission, except for the Englewood project. Commissioner De Ronde resigned as chair of the roads subcommittee in favor of Col. Edwin A. Stevens, who had raised objections about Leavitt’s performance. During his career, Leavitt would claim many laudable accomplishments, including construction of the Yale Bowl, but his relationship with the commission was becoming untenable.

On Leavitt’s staff was young engineer William Addams Welch. Welch caught the eye of Perkins, who recruited him to the commission as an assistant engineer. Before Welch concluded his career forty years later, he would blaze a path in park development and management second to none in the United States.

Welch’s family connection to the Hudson River Valley was represented by “Welch Island” in the headwaters of the Hackensack River, named for an ancestor who had settled in the region in 1695. The Welch roots extended even further back to Plymouth, Massachusetts, where John Welch landed soon after the Mayflower colonists. The Welch family migrated west to New Jersey, then westward again before the Revolutionary War. The family settled in Kentucky, where William Welch was born in 1868. Welch’s father had ridden with Morgan’s Raiders during the Civil War. His mother, Priscilla Addams, was descended from John Adams, second president of the United States. An extra “d” had been added to the name when the Southern branch of the family disagreed with the policies of John Quincy Adams, the sixth U.S. president.

Welch attended college in Colorado and Virginia. On graduation, he worked on engineering projects in Alaska for six years, then in the western states, Mexico, and South America, where he specialized in railroad construction. Yellow fever caused him to return to the United States, where, in private practice, he designed the beautiful Havre de Grace racetrack in Maryland and built the boardwalk at Long Beach, Long Island. When he was tapped by Perkins to join the commission, Welch, with no park experience, stepped into untested territory. But long before his career ended, park advocates from all over the United States and Europe would be seeking him out for advice and guidance at his small, secluded Bear Mountain cabin. Welch, who granted no interviews with the press and sought no personal accolades, became the “father” of the state-park movement and greatly influenced the creation of the National Park Service.

One of his passions was the construction of camps for children. During his tenure, 103 children’s camps would become available within the park system capable of accommodating a total of 65,000 children each summer season. Eleanor Roosevelt attended the dedication of one of these camps. Given the honor of breaking a bottle of champagne over a boulder, Roosevelt swung hard and missed, hitting Welch in the head. As reported in the New York Times, “After he came to, the ceremonies were resumed.”