Читать книгу Lie on your wounds - Robert Sobukwe - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1960–1962

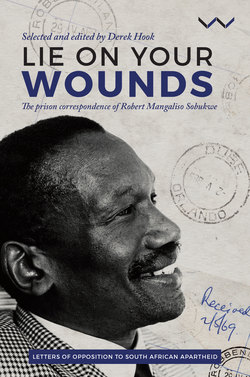

After Sobukwe’s arrest on 21 March 1960, he was taken to the clinic where his wife worked, for a police search. The photograph shows Veronica and Robert Sobukwe, along with a security policeman, entering the clinic.

Robert Sobukwe

to Major-General C.I. Rademeyer,

Commissioner of Police,

Cape Town, 16 March 1960

Sir,

My organization, the Pan Africanist Congress, will be starting a sustained, disciplined, non-violent campaign against the Pass Laws on Monday the 21st March 1960. I have given strict instructions, not only to members of my organization but also to African people in general, that they should not allow themselves to be provoked into violent action by anyone. In a Press Statement I am releasing soon, I repeat that appeal and make one to the police too.

I am now writing to you to instruct the Police to refrain from actions that may lead to violence. It is unfortunately true that many white policemen, brought up in the racist hothouse of South Africa, regard themselves as champions of white supremacy and not as law officers. In the African they see an enemy, a threat, not to “law and order” but to their privileges as whites.

I therefore, appeal to you to instruct your men not to give impossible commands to my people. The usual mumbling by a police of an order requiring people to disperse within three minutes, and almost immediately ordering a baton charge, deceives nobody and shows the police up as sadistic bullies. I sincerely hope that such actions will not occur this time. If the police are interested in maintaining “law and order,” they will have no difficulty at all. We will surrender ourselves to the police for arrest. If told to disperse, we will. But we cannot be expected to run helter-skelter because a trigger-happy, African-hating young white police officer has given hundreds of thousands of people three minutes within which to remove their bodies from [the] immediate environment.

Hoping you will cooperate to try and make this a most peaceful and disciplined campaign.

I remain

Yours faithfully,

Mangaliso R. Sobukwe

President

Pan Africanist Congress

PAC press release announcing

anti-pass campaign,

18 March 1960

CALL FOR POSITIVE ACTION

In accordance with a resolution adopted at our National Conference, held in Orlando on the 19th and 20th December, 1959, I have called on the African people to go with us into Positive Action against the Pass Laws. We launch our campaign on Monday, the 21st of March 1960, and circulars to that effect are already in the streets.

Meaning of campaign: I need not list the arguments against the Pass Laws. Their effects are well known. All the evidence of broken homes, tsotsism1 and gangsterism, the regimentation, oppression and degradation of the African, together with the straight-jacketing of industry leads to one conclusion, that the Pass Laws must go. We cannot remain foreigners in our own land.

I have appealed to the African people to make sure that this campaign is conducted in a spirit of absolute non-violence, and I am quite certain that they will heed my call. I now wish to direct the same call to the police. If the intention is to “maintain law and order,” I say, you can best do so by eschewing violence. Let the Saracens2 have a holiday. The African people do not need to be controlled. They can control themselves. Please do not give my people impossible orders, such as “disperse within three minutes.” Any such order we shall regard as merely an excuse for baton-charging and shooting the people. If the African people are asked to disperse, they will do so orderly and quietly. They have instructions from me to do so. But we will not run away! If the other side so desires, we will provide them with the opportunity to demonstrate to the world how brutal they can be. We are ready to die for our cause; we are not yet ready to kill for it.

Finally, I wish to offer all those non-African individuals and groups who have expressed themselves as bitterly opposed to the Pass Laws, an opportunity to participate in this noble campaign which is aimed at obtaining for the African people those things that the whole civilized world accepts unquestioningly as the right of every individual. Here is an opportunity for you to create history. Be involved in this historical task; the noblest cause to which man can dedicate himself – the breaking asunder of the chains that bind your fellowmen.

Remember: “Every man’s death diminishes me. For I am involved in mankind.”3

Mangaliso R. Sobukwe

PRESIDENT

PAN AFRICANIST CONGRESS

Robert Sobukwe to the Registrar,

University of the Witwatersrand,

21 March 19604 (Aa11)

I hereby wish to tender my resignation from the position of Junior Language Assistant in the Department of Bantu Languages.

Circumstances have arisen which make it necessary, in the interests of the university, that I resign and that my resignation take effect from the earliest date the university may decide.

I wish to thank you for the attitude you adopted in refusing, in the face of terrific pressure, to interest yourself and the university in my political life.5

Thank you

Yours sincerely

R.M. Sobukwe

The Registrar,

University of the

Witwatersrand,

to Robert Sobukwe,

22 March 1960 (Aa10)

Dear Mr. Sobukwe

I have to acknowledge receipt of your letter dated 21st March, 1960, wherein you tendered your resignation from the post of Junior African Language Assistant on the staff of the Department of Bantu Languages at this University.

I note that you wish your resignation to take effect from the earliest date that the University may decide, and I have to advise you that it will take effect as from 31st March, 1960, after which date you will no longer be a member of the University Staff.

Yours sincerely,

A. de V. Herholdt.

Registrar.

Robert Sobukwe,

Witbank Prison,

to Veronica Sobukwe,

[1961] (Bc43)

Darling,6

I am now at the Witbank Prison, as the address above indicates. I am quite well and would ask you not to be anxious about my health.

The distance from Johannesburg is much greater than it was to Stofberg [Prison] and you might find transport costs prohibitive. Don’t strain your resources.

We are allowed to read approved books and I shall be glad if you will collect two books from Uncle which I left at his place.

We are in open country once more and for that I am thankful. One can see far into the distance.

Give my love to the kids, particularly to Zodwa,7 the best of them all? Please inform me, when you reply, how Mili8 is faring at school.

Cheerio Little Woman.

Your loving husband,

Mangaliso

Robert Sobukwe,

to Benjamin Pogrund,

Pretoria Gaol,

4 October 1961

(Ba1.1)

Dear Benjie,

I have about five letters to reply to and yours was the last to arrive. But I have decided to indulge in a bit of favouritism and write your letter first. Thanks indeed for your letter. It was a real pleasure to read it.

Through the kind permission of the prison authorities, I am able to write and receive one letter per week and have one visit per week. I have, therefore, been able to write regularly to my people in Graaff-Reinet and also to see my wife. Unfortunately children are not permitted inside the grounds, so I last saw my kids at Witbank [Prison].

Thanks for the news about Jennifer.9 I had not received the glad tidings yet. I am glad to have got the news from the proud father himself. Since both of you are so easy to please I don’t think Jennifer’s task, to make you happy, should be a difficult one! I am sorry I cannot come and pay my respects in person to the lady, but hope to do so when I have left gaol.

My daughter is in Basutoland, attending school there. I learn that two weeks ago she was taken ill and that my wife has rushed to Basutoland to see her. Haven’t heard any more since then.

Glad to learn you have taken up Zulu again – particularly Astrid. I was sorry when she had to give it up because of your interference.10

Thanks for remembering me, Benjie – and thank you also for your offer of help. As I said earlier, I am allowed a visit per week so that it should be possible to arrange for my wife to skip one week so that I may meet you.

Zeph11 and Jacob12 remained behind at Witbank. I am with P.K.13 And we both would be happy to see you. You may perhaps be able to send me some books to read. We are allowed to receive approved literature – that EXCLUDES Westerns.

Give my greetings to Astrid and the kid. I wish them the very best. Remember me to Pat14 and Dave15 when you do write to them.

Salani kahle!16

Yours very sincerely

Bob

Robert Sobukwe, Pretoria Gaol,

to Veronica Sobukwe,

19 June 1962 (Bc1)

Darling,

Thank you for your note which I received on Friday. I was extremely sorry to learn that you had come here on the 11th and were turned away. The truth is, child, I have NOT had a visit this month. I do not know the Dan Mabena who is supposed to have visited me. I have never met him when outside or inside jail. I really cannot explain how the mistake occurred because whenever we receive visits we have to produce our tickets from which our particulars are taken. The person who had a visit on the 10th was Stanley but he, too, was not visited by a Dan Mabena. I reported the incident to the Chief and explained the error to him. Of course he, too, could not have done otherwise if it was recorded in the register that I had received a visit. He has, however, undertaken to have the matter put right, so that if you are able, you may still visit me before the end of the month.

I am quite aware, of course, of the difficulties facing you now, with schools about to close – the children’s train fare and boarding fees to be paid and arrangements for their clothing and general comfort to be made. If then, you find it impossible to come this month, I will understand, Little Woman. I know what it feels like to undertake a journey full of hope and expectations only to meet disappointment. But as you will remember, I have often said to you that I shall not agree to see anybody unless they come with you, or, if you are for some reason or another unable to make the trip that month, you have informed me that somebody else will be coming to see me.17 I abide by that decision.

I found myself thinking often about you and the children during these cold winter mornings, picturing you standing at [illegible] waiting for the bus. [Illegible] and back again in the afternoon. It has been a hard year, Little Woman, don’t you think so? But please remember that “He who goes out weeping to sow his seed comes back joyfully carrying his sheaves.”18 Happiness is achieved through suffering and struggling.

I received a letter from Mlamli.19 He wrote from Cape Town and asked me to send the reply to his home in the Transkei. I have, unfortunately, forgotten his Transkeian address. I know it is P.O. St Mark’s but I cannot recall the shop through which he receives his mail. Please ask Selby to find out from either Dennis or Fazzie. If neither of them knows it then he should try Nomvo Booi, P.O. Box 8, Engcobo. She will know.

How are the children getting on? I can imagine Dedani on a cold morning, reluctantly leaving the house for school. Where do you leave them on Saturdays and Sundays? And by the way, have you been on night duty already this year? I hope your turn does not come next month when the children are at home. Have the Mahlangus next door not yet added to their family after Thabo? What about Hilda?20 She promised to drive up to Johburg in a Belaire or Biscayne21 pretty soon – that was in 1959 when I was down in Durban. What is the news about the Varas? I wrote to Mercy last month. She has not replied yet. I want to write to Charles22 next and ask him to make up his mind once and for all, whether he still wants his wife back or not. Their son is over fourteen years old now.

I am writing to Mam Tshawe23 today. I have not written to her personally since I came to jail. I fear that she might feel hurt at the neglect. Buti hinted that she has a lot to tell me about Cape Town. But that, of course, will be when we meet.

Well, Greetings to Mama and the kids. How is Jabie24 getting on? I enjoyed her book a great deal. Is Shadrach making any progress with the ceiling? Now that I remember, he is not fond of working alone you know. Even when we asked him to fit the doors and the skirting board it was only when Meshach assisted him that the job was completed. If he is slack, it might not be a bad idea to see his wife and first inform her about his negligence. She will undoubtedly get him to finish the job. Is Rosette back with Five Roses25 or is he employed somewhere else?

Cheerio, Kid.

Your loving husband,

Mangi

1Petty crime.

2Military vehicles used by the South African Police.

3From “No Man Is an Island” by John Donne.

4Monday, 21 March 1960, was the day that Sobukwe led the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC) in its anti-pass demonstrations. The restrictive and oppressive pass system, which required all black South Africans to carry an identity document (also known as the dompas), regulated and controlled movement, specifying whether a person was allowed to be in a particular area. To be found in an area not specified by one’s pass – as, for example, in white residential areas – meant one could be immediately arrested. As Benjamin Pogrund (2015: 2) tells us: “The pass laws were hated as the tangible evidence of black subjugation, and for the ravaging effect on the lives of millions upon millions of people. Sobukwe had called on blacks to end the pass laws by making the system inoperable through mass arrests, thus clogging the courts and prisons by weight of numbers.” This mass action resulted in the Sharpeville massacre – later that same day – in which at least 69 people were killed by the South African Police, who opened fire on a crowd of protesters outside the police station in the township of Sharpeville, near Vereeniging. This event, which drew international attention to the injustices and brutality of apartheid, was a turning point in the history of the country, and indeed, in the history of resistance to white supremacy.

5A reference, no doubt, to the government threats the university would have faced once it became known that Sobukwe was the leader of the PAC.

6Zondeni Veronica Sobukwe (1927–2018) married Robert Mangaliso Sobukwe on 6 June 1954 in a traditional African ceremony where she received the bridal name of Nosango. Veronica – as she is most frequently known in the letters – came later to be referred to variously as Mama Sobukwe and “the mother of Azania”. She was honoured in a poem by Es’kia Mphahlele entitled “Tribute to Zodwa Veronica, a Great Woman”. She worked for much of her life as a midwife and health practitioner. At the time of her husband’s imprisonment, she was a midwife in Soweto.

7Sobukwe often uses “Zodwa” to refer to Veronica in the letters.

8Miliswa was the eldest of Sobukwe’s four children. The letters contain frequent references also to Sobukwe’s other children, Dinilesizwe and the twins, Dalindyebo and Dedanizizwe. Motsoko Pheko (1994) tells us that the name Dinilesizwe means “Sacrifice of the Nation”, Dalindyebo “Create Wealth” and Dedanizizwe “Give Way, Imperialists”.

9Pogrund’s daughter, born in July that year. She would go on to study at the University of Cape Town and then at Columbia University, New York, and gain a master’s in international relations. Besides being a film-maker – between 1991 and 1992 she produced and directed a documentary film on Nelson Mandela entitled The Last Mile – she is today a member of the Department of International Relations and Cooperation (DIRCO) in Pretoria, where she is on the European Union desk.

10Sobukwe’s joking tone is obvious here. As Pogrund (2015) confirms, Sobukwe is referring here to Astrid’s dropping out of university after her marriage to Pogrund.

11Zephaniah Mothopeng (1913–90), like Sobukwe, had been a member of the Africanist faction of the ANC Youth League which broke from the ANC to form the PAC. Mothopeng was made chairman of the PAC on 6 April 1959, at the same inaugural conference at which Sobukwe was voted president. Like Sobukwe, he was arrested in 1960 for his part in organising the anti-pass campaign. He was subsequently sentenced to serve three years on Robben Island, although, because Sobukwe was kept apart from the rest of the prisoners, they had no contact during this time.

12Jacob Dumdum Nyaose (1920–) became the secretary for labour in the PAC’s national executive committee in April 1959. Later that same year he created the Federation of Free African Trade Unions of South Africa, an all-African non-Communist union.

13Potlako Leballo (1924–86) had been a leader in the ANC Youth League (c.1954), who, like Sobukwe, was critical of the ANC’s leadership, and who broke with the organisation to form the PAC. He was made national secretary at the PAC’s inaugural conference (1959), and was sentenced to two years in prison following the declaration of a state of emergency in March 1960. Although a new banishment order was served on him when he was released in 1962, he escaped and fled to London. He subsequently established the PAC headquarters in Dar es Salaam, and served as leader of the PAC. (For more on Leballo, see Bolnick, 1991.)

14Patrick Duncan (1918–67) had been owner and editor of the liberal magazine Contact, and was described by Pogrund (2015: 64) as “a man of intense sincerity and moral commitment to non-racialism”. He participated in the Defiance Campaign of 1952. He acted as a national organiser for the new Liberal Party, from which he resigned in 1963 on the grounds that he no longer agreed with the party’s policy of non-violence. Banned by the South African government, he escaped to Basutoland. He was accepted as a member of the PAC in 1963 and became its representative in North Africa, based in Algeria.

15David Du Bois (1925–2005) was the director of the United States Information Service (USIS) in Johannesburg. He was known to Sobukwe through Potlako Leballo, who had found employment at the Johannesburg office of the USIS.

16Keep well!

17Sobukwe’s wording is a little confusing here. He is conveying his intent not to accept visitors unless they are accompanied by his wife, or unless his wife has informed him of who they are and given him advance warning.

18Psalm 126: 6.

19Clarence Mlamli Makwetu (1928–2016), who was secretary of the PAC in Langa, Cape Town, before the PAC was banned. He was imprisoned on Robben Island from 1963 to 1968 in the same jail as Nelson Mandela and other ANC members. When the PAC was unbanned in 1990, he became its president.

20Veronica’s older sister.

21The Bel Air and the Biscayne were contemporary models of Chevrolet motor cars.

22Robert Sobukwe’s brother.

23The wife of Sobukwe’s brother Ernest.

24Veronica’s younger sister.

25The tea manufacturer.