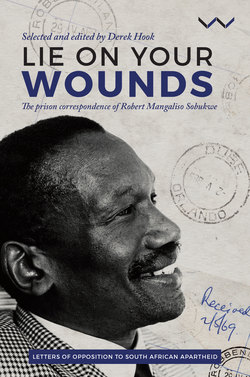

Читать книгу Lie on your wounds - Robert Sobukwe - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

In a letter of condolence written on 5 August 1974 to Nell Marquard, a friend with whom he had been corresponding since his time on Robben Island, Robert Mangaliso Sobukwe made a telling observation:

I learnt some time ago that one cannot put oneself in another’s position. We may express sympathy, feel it and even imagine the pain. But we cannot feel it as the one who suffers it. They have a saying in Xhosa that the toothache is felt by the one whose tooth is aching.

Sobukwe, who clearly knew about suffering, loneliness and the impossibility of ever fully communicating one’s pain to another, was writing just after the death of Nell’s husband, the noted Cape liberal, author and historian, Leo Marquard. Given that Leo was a prominent liberal, and that white liberals had not always been friendly to the aims and agendas of the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC) – the organisation that Sobukwe led from 1959 until his arrest in 1960 – one might have expected coolness from Sobukwe. Not at all. Sobukwe, as always, was gracious:

I am thankful that I was able to talk to you two years before Leo’s death and more thankful that he died knowing how much his contribution had been appreciated.

Touching as this acknowledgement of his contribution would have been for Marquard, the real poignancy of Sobukwe’s letter comes a little further on, when he starts speaking of the myriad difficulties he has faced since leaving Robben Island.

It has not been a good year for me. I had planned to leave [from Kimberley] … by car on the 31st May and make straight for Cape Town. But these boys beat me to it. They came on the 30th May, 1974 to serve the fresh lot of bureaucratic output. Well it’s good to know that our security is entrusted to such alert people.

Despite the fact that he makes light of it, one senses in Sobukwe’s letter that the constant surveillance and harassment of the Security Police was taking its toll. Behind the ironic salute to the astuteness of the police, there is also a disturbing foreshadowing. Steve Biko, in many respects Sobukwe’s most direct political heir, would be stopped and arrested on a not dissimilar road trip from Cape Town four years later, an event which would lead directly to his death at the hands of the Security Police. Sobukwe continues:

Veronica has had a major operation as you probably read in the papers. She should have had this operation last year, but did not and the condition got worse.

She has made a remarkable recovery, thanks to my very efficient and tender nursing, and has now gone back to Joh’burg for a check up. From there she will be in Durban to spend a week or so with her sister before proceeding to Swaziland to see the children.

These understated lines could only have masked Sobukwe’s sadness and frustration at not being able to accompany his wife in this time of need, at being apart from his children, and at being alone again after his ordeal of six years of near-complete solitary confinement (May 1963 – May 1969) on Robben Island.

These circumstances had their origins in a momentous historical event organised by Sobukwe himself. On 21 March 1960, Sobukwe had led the PAC in what he called a “positive action” campaign, protesting against the oppressive pass laws that governed the movements – and indeed the lives – of black South Africans. This mass action resulted in the Sharpeville massacre, later that same day, in which at least 69 people were killed when the South African police opened fire on a crowd of protesters. This event, which drew international attention to the injustices and brutality of apartheid, was a watershed moment in the history of South Africa, and it led to a three-year jail sentence for Sobukwe for inciting people to protest against the laws of the country.

Sobukwe, inside the grounds of Orlando Police Station, awaiting arrest, on the morning of 21 March 1960.

Not content that by 3 May 1963 Sobukwe would have served the three years of his sentence, the South African government intervened by passing an amendment to the General Law Amendment Act, the notorious “Sobukwe Clause”, which enabled Parliament to prolong the detention of any political prisoner year after year. Sobukwe was then relocated to Robben Island, and kept apart from other prisoners – technically, he was no longer a prisoner as he had served his sentence – where he remained for six years. The clause – never used to detain anyone else – was renewed annually by the Minister of Justice.

Sobukwe, in a very significant sense, was never a free man again after his 1960 arrest and imprisonment. The apartheid government unleashed a series of bureaucratic cruelties upon Sobukwe after his May 1969 release from Robben Island. They forced him to live in the geographically remote town of Kimberley – far removed from any friends, family or associates; they insisted he take on a low-ranking job that would have made him complicit in the apartheid policies that he went to jail protesting (Sobukwe, needless to say, refused); they repeatedly refused to allow him to leave the country to take up offers of employment he had received from the United States; and they obstructed his attempts to access the medical treatments that he needed, and that could have extended his life (he died on 27 February 1978).

This then is the background to the consolations that Sobukwe sought to offer Nell Marquard in his 1974 letter. It is only on the last page of that letter that Sobukwe seemed finally to find the words that suited both his emotions and the note of commiseration that he wished to convey to Nell:

The Xhosa have standard words of condolence. They say

Akuhlanga lungehlanga hala ngenxeba

(There has not occurred what has not occurred before … LIE ON YOUR WOUND).

God bless you.

Affectionately

Robert.

Whether he realised it or not, Sobukwe had used the same phrase in a letter to Nell written six years earlier (on 26 June 1968) on Robben Island:

We have a saying in Xhosa, used for purposes of condolence. It is a little stoic: akuhlanga lungehlanga – lala ngenxeba: (Daar het nie gebeur wat nie al gebeur het nie: slaap op jou wond).

This resonant phrase – which also appears in Sobukwe’s letters to his friend Benjamin Pogrund – applies equally, if not more so, to Sobukwe himself. “Lie on your wound(s)” is a call to bide one’s time, to heal, and to reconstitute one’s self despite evident suffering. It is a call to have courage, to bear the moral burden of pain, and it provides an apt title for what was the most difficult period of Sobukwe’s life, namely his time on Robben Island, which the selection of letters collected in this book represents.

* * *

In a personal note, written in 1986, eight years after his death, Nell Marquard (1986: 8) provided an insightful characterisation of Sobukwe’s letters:

A letter from Robert was always an event. His “mundane” included talk of books and articles, happenings in the outside world, education, gardening in the arid soil of Kimberley, and much more. His comments were always interesting and thought-provoking. But what gave his letters their chief interest was the quality of the man himself. The tacit assumption of standards was not infrequently underlined by gentle irony. Humane, compassionate, humorous, his letters were a constant pleasure.

Robert Sobukwe and Benjamin Pogrund, Kimberley.

This is true. Despite the conditions of censorship – all of Sobukwe’s correspondence was carefully monitored by the Security Police and the island's warders – his erudition, his unwavering interest in global events, and his love of literature are all clearly evident in the letters. As is his sense of humour. Responding, on 26 June 1968, to a card that Marquard had incorrectly dated before sending to him, Sobukwe remarked:

Thank you for both your card of the 1st June 1868 and your letter of 8th June, a century later. I have been long on this island, haven’t I?

Sobukwe possessed not only a political, but also a wonderfully literary mind. He taught African languages at the University of the Witwatersrand (hence the nickname of “Prof”); he dreamed of translating Shakespeare into Zulu; he planned to study Arabic while on Robben Island; and he could cite Afrikaans poetry – particularly that of Jan Celliers – by heart. The letters are as engaging as they are eclectic. It is not unusual in a Sobukwe letter for a biblical reference to follow after a recalled snippet of Russian poetry, for a citation from Tennyson or Wordsworth to accompany a memory of his formative years in Graaff-Reinet, or for a Xhosa proverb to be interlaced with thoughts on the characters of Lyndon Johnson or Robert Kennedy. Sobukwe the letter-writer moves seamlessly from discussion of the history of the Xhosa people to the new boxing world heavyweight champion, from the relative merits of Christianity and Judaism to Kwame Nkrumah’s notion of the African Personality.

Thanks to the efforts of the Rand Daily Mail journalist, Benjamin Pogrund, – by far Sobukwe’s most regular correspondent in the collected letters that follow – Sobukwe received a great many books, as well as newspapers and journals (when permitted, that is) during his time on Robben Island. Sobukwe clearly had great flair in analysing global political events – such as the 1968 protest movements sweeping across Europe, the state of China–US relations, the 1966 coup d’etat in Nigeria – events which, as he tells Pogrund, formed the historical context necessary for understanding the South African situation (“There is a verligte-verkrampte [progressive-conservative] battle royal raging all over the world,” he laments to Marquard in his letter of 27 March 1968). Many of the letters are surprisingly topical, even today – see, for example, Sobukwe’s comments on mass immigration into Britain in his 5 June 1968 letter to Marquard – just as his political views are not always easy to predict – he was not, as one might expect, a supporter of Robert Kennedy, and he admired Lyndon Johnson despite his role in prolonging the Vietnam War.

None of this is to imply that either Sobukwe or his correspondents could speak freely in the letters. Nor is it to suggest that communication between parties was uninterrupted or without restriction. Sobukwe was allowed to receive and write only a limited number of letters. Length of letter was also controlled. As Benjamin Pogrund explained to me, all letters were subject to capricious censorship: if some faceless security warder did not like a sentence or perhaps a word, the entire letter was withheld, without telling Sobukwe or the author of the letter. It could take months to realise that a letter had been seized. As Pogrund (2015: 194) recalls:

the official hold-up of letters was maddening. It was made even worse by the arbitrariness of the censorship. I never once received a letter from him with any part blacked out; what the authorities did was to seize letters and not tell either of us that they had done so. It might have been that a single sentence – or a single word? – offended some faceless security official. Whatever it might be, the entire letter disappeared … it could take several months before it dawned on me that I was not getting Sobukwe’s reply on an issue I had raised because the letter hadn’t got through to him, or a letter from him had been blocked.

Even more seriously, the contents of the letters were scrutinised for any signals as to whether Sobukwe might have changed his political views. The implications of a stray phrase or unintended implication could have very serious consequences. As Pogrund (2015: 207) recalls:

I was … more conscious than ever that some or other comment or bit of information … might actually help prolong his imprisonment. I spent hours writing and re-writing letters, trying to convey as much as possible but frightened of saying the wrong thing, without a clear idea as to what the wrong thing might be. Blandness and banality was the safe way out, as was discussion about his needs and reports about my young daughter.

Robert Sobukwe’s four children, Dini and Miliswa (back row) and the twins Dali and Dedani (in matching jerseys) with Pogrund’s daughter Jenny and another friend (looking into the camera).

These are important comments to bear in mind when reading the letters that follow. This selection of letters is, importantly, incomplete. Perhaps this is obvious, for only a portion of the letters received or sent by Sobukwe during his years of imprisonment survive. Some of the surviving letters, furthermore, are not particularly clear or even legible. Where I have been unable to decipher words or passages, these have been indicated in the text by [illegible]. Where I have omitted passages that have personal references to people still alive, I have indicated this by […]. I have supplied, with each letter, the reference number corresponding to the cataloguing system used by the Historical Papers Research Archive at the University of the Witwatersrand for ordering the Robert Sobukwe Papers. (See: http://www.historicalpapers.wits.ac.za/index.php?inventory/U/collections&c=A2618/R/6325). Providing this reference number – just after the date of each letter (for example: Ba3.41) - allows readers to refer back to the original (often handwritten) letters, many of which are available online.

We have, then, a collection of letters that is both necessarily incomplete (we do not have access to Nell Marquard’s letters to Sobukwe, for instance) and that includes many instances of correspondence not directly written to or by Sobukwe (such as the letters by Veronica Sobukwe and Benjamin Pogrund). The latter are included because they play an invaluable part in grounding the personal and historical context of Sobukwe’s letters. Particularly noteworthy here are the letters that Veronica Sobukwe and Benjamin Pogrund wrote to B.J. Vorster, then Minister of Justice (on 4 March and 3 February 1966, respectively), and Pogrund’s exchange of letters with Helen Suzman in April and May 1969.

I have tried to let the letters speak for themselves in the sense of adding only minimal annotations. Unnecessary commentary on my part would only have distracted from the content of the letters themselves. I have, however, added footnotes on significant historical figures or events that help contextualise what is being spoken about. This too remains an incomplete process. Despite many online searches and the generous help of both Benjamin Pogrund and Miliswa Sobukwe, I have not been able to identify everyone – or every event – mentioned in the letters. At first this struck me as a limitation. It then occurred to me that my task as editor was less to explain the letters than to arrange and present them. As such, my hope is that the letters can be read not only as a historical document, but as an epistolary novel which calls us to become imaginatively involved in the life of an at once inspiring and humbling figure whom South Africa has for too long neglected: Robert Mangaliso Sobukwe.