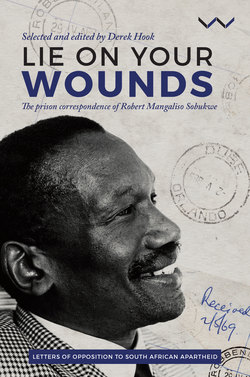

Читать книгу Lie on your wounds - Robert Sobukwe - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPreface

By Otua Sobukwe

My Robben Island Awakening

During the apartheid regime, Robben Island was the most notorious prison in South Africa. Enclosed in its prison walls were struggle icons whose names we continue to celebrate today – Sisulu, Mandela and many other unsung heroes. Amongst them but purposely separated was Robert Sobukwe, a freedom fighter who was banned to solitary confinement for leading an anti-pass march campaign that galvanised people on the path to the country’s democracy. About thirty years later, the same island became the home of a young, adventurous little girl – me; his granddaughter. I lived on the island with my uncle who worked there for 8 months.

Paradoxically, Robben Island is one of the most beautiful places in the world. But when you put yourself in the shoes of a prisoner, there comes a shift of perspective.

Suddenly, things begin to lose their beauty.

The blueness of the sky loses its colour, as candyfloss clouds morph into grey patches, the singing tune of seagulls begins to mimic a pained cry, the once tranquil ebb and flow of the sea is now melancholic, yearning, and, more so, the mainland, its shimmering lights, their faintness, is no longer picturesque, no longer romantic, but just a cold reminder of the separating distance and the harsh reality, the harsh juxtaposition, that you are indeed alone.

The seven-year-old me was oblivious to this atmosphere of solitude. The place where my grandfather stood for his battle, longed for his family, and wept in his loneliness was the same place that framed my warm, explorative childhood. I didn’t realize the weight of the island nor the significance of its history.

But ten years later, I understood. Intimately complex and profound – I realised that somehow my surroundings had brought me closer to a man that I had never met and opened my eyes to an identity I had never fully grasped.

That my roots are of an African soil has never been an incongruity to me. I have always wholly embraced my African identity; I am of its branches, its rivers, its auburn sunsets. However, when I returned to Robben Island, now seventeen, it occurred to me, this sudden epiphany, that I am not only a reflection of Africa, but a continuation of AfriKa. And these two Afric(k)as are not the same; one is the vessel and the other the spirit.

I stood there, in its beauty. My Afrikan seed beginning to germinate, I let my grandfather’s words “Love your Afrika” water my roots, and as I felt the connection of our souls, it dawned on me, quite frighteningly, but beautifully too, that I am not only of his blood, but of his battle.

You see, Africa is not free, I whispered. She is a frightened bird in a rusting cage, with bent bars painted in crusting promises. She limps on a beaten leg too exhausted to bleed and bows her head when she speaks. She needs to be freed. But only Afrika can free Africa.

Like most young people, I didn’t get this at first. My life was my own and my goals were fixed. I didn’t understand that there was a continental vision or an ancestral goal that I was intertwined with. Yet the clues were there, my grandfather being one.

What Sobukwe started in South Africa, the unconditional passion he devoted to his movement, I realized, was the same fire that would ignite mine, whatever it be, in my life. Energy can never be created or destroyed, but only transferred or changed from one form to another.

And so there I was. A growing, energised Afrikan plant. One that would grow tall and blossom and, as if self-pollinating, return to its home, my Afrika, and give back to what it previously could not help fix. For education was three things: One, to break the shackles of my circumstance and end the cycle of my poverty. Two, to achieve a monumental freedom which my grandfather was never granted. And three, to be part of the key that would one day release the frightened bird.

How ironic life is, that Robben Island prison was to me not only a home, but one of the most liberating experiences of my life. And so, it is in this spirit that I encourage you to read the letters that my grandfather Sobukwe wrote, because captured in his words is not only his pain, but the beauty of his pain as a sacrifice for freedom.