Читать книгу The Life and Times of Queen Victoria (Vol. 1-4) - Robert Thomas Wilson - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

CHAPTER II.

EARLY EVENTS OF THE NEW REIGN.

ОглавлениеTable of Contents

First Council of the Queen—Her Address to the Assembled Dignitaries—Admirable Demeanour of the young Sovereign—Proclamation of Queen Victoria—Condition of the Empire at the Time of her Accession—Character of Lord Melbourne, the Prime Minister—His Training of the Queen in Constitutional Principles—Question of the Royal Prerogative and the choosing of the Ministry—Removal of the Queen to Buckingham Palace—First Levee—Her Majesty’s Speech on the Dissolution of Parliament—Amelioration of the Criminal Laws—Results of the General Election—Meeting of the New Legislature—The Civil List fixed—Relations of the Queen towards the Duchess of Kent—Daily Life of her Majesty—Royal Visit to the City—Insurrection in the Two Canadas—Measures of the Government, and Suppression of the Revolt—The Melbourne Administration and Lord Durham—Reform of the Canadian Constitution.

We now resume our narrative of what happened on the first day of the new reign—the 20th of June, 1837. At eleven o’clock in the forenoon—the appointed hour—Queen Victoria, attended by the chief officers of the household, entered the Council Chamber, and seated herself on a throne which had been placed there. The Lord Chancellor (Cottenham) then administered the customary oath taken by the sovereigns of England on their accession, in which they promise to govern according to the laws. The Princes, Peers, Privy Councillors, and Cabinet Ministers, next took the oaths of allegiance and supremacy, kneeling before the throne; and the first name on the list was that of Ernest, King of Hanover, known to Englishmen as the Duke of Cumberland. The Queen caused these distinguished persons to be sworn in as members of the Council, and the Cabinet Ministers, having surrendered their seals of office, immediately received them back from her Majesty, and kissed her hand on their reappointment. Having ordered the necessary alterations in the official stamps and form of prayer, the Council drew up and signed the Proclamation of her Majesty’s accession, which was publicly read on the following day. But one of the principal incidents of that memorable Council was the reading by the Queen (previously to the surrender of the seals by the Ministers, and their reappointment) of an address which ran as follows:—

“The severe and afflicting loss which the nation has sustained by the death of his Majesty, my beloved uncle, has devolved upon me the duty of administering the government of this Empire. This awful responsibility is imposed upon me so suddenly, and at so early a period, that I should feel myself utterly oppressed by the burden, were I not sustained by the hope that Divine Providence, which has called me to this work, will give me strength for the performance of it, and that I shall find, in the purity of my intentions, and in my zeal for the public welfare, that support and those resources which usually belong to a more mature age and longer experience. I place my firm reliance upon the wisdom of Parliament, and upon the loyalty and affection of my people. I esteem it also a peculiar advantage that I succeed to a sovereign whose constant regard for the rights and liberties of his subjects, and whose desire to promote the amelioration of the laws and institutions of the country, have rendered his name the object of general attachment and veneration. Educated in England, under the tender and affectionate care of a most affectionate mother, I have learned from my infancy to respect and love the constitution of my native country. It will be my

GATEWAY OF ST. JAMES’S PALACE

unceasing study to maintain the reformed religion as by law established, securing at the same time, to all, the full enjoyment of religious liberty; and I shall steadily protect the rights, and promote to the utmost of my power the happiness and welfare, of all classes of my subjects.”

The demeanour of the Queen on this difficult and agitating occasion is described as composed and dignified. She received the homage of the nobility without any undue excitement, and her delivery of the address was an admirable specimen of the clear and impressive reading to which her Majesty has since accustomed the public. Occasionally she glanced towards Lord Melbourne for guidance; but this occurred very seldom, and for the most part her self-possession was extraordinary. The quietude of manner was now and then broken by touches of natural feeling which moved the hearts of all present. Her Majesty was particularly considerate to the Royal Dukes, her uncles; and when the Duke of Sussex (who was infirm) presented himself to take the

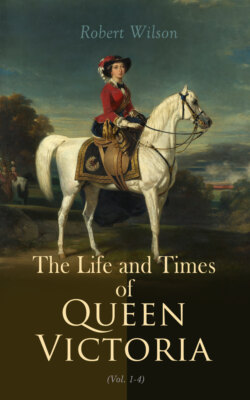

QUEEN VICTORIA AT THE TIME OF HER ACCESSION.

oath of allegiance, and was about to kneel, she anticipated his action, kissed his cheek, and said, with great tenderness of tone and gesture, “Do not kneel, my uncle, for I am still Victoria, your niece.”

On the whole, that day was the most memorable in the Queen’s life, and its effects were seen next morning in an aspect of pallor and fatigue. An inexperienced girl, only just eighteen, had been invested with a power which carried with it the gravest responsibilities towards innumerable millions; and she had for the first time to discharge the duties of the State—duties of which she could have had no practical knowledge until then—under the affliction of a personal loss, for there can be no doubt that she was attached to her uncle, the late King. The lonely height of regal splendour was never more sharply or intensely felt than by that young Princess in the first hours of her grandeur and her burden. It is true that the death of King William was not unexpected, and that his niece had for some years been familiarised with the fact that, in the ordinary course of nature, she would one day succeed to the crown. But death is always surprising when it comes, and the new monarch had seen little of the ceremonial life of courts before her elevation to the throne. Owing to the temporary failure of health to which we have alluded, the Princess had not been made fully aware of her destiny until after she had entered her twelfth year. She had probably thought but little of the future in the intervening time; and at eighteen she was called upon to administer the affairs of a vast Empire, full of varied races, of complex interests, and of unsettled problems.

The new sovereign was proclaimed under the title of “Alexandrina Victoria”; but the first name has not been officially used since that day. The appearance of the Queen at one of the windows of St. James’s Palace, on the morning of June 21st, was greeted with immense enthusiasm by a vast crowd of people who had assembled to hear the Proclamation read, but who did not anticipate that the sovereign would present herself. At ten o’clock, the guns in the Park fired a salute, and immediately afterwards her Majesty stood conspicuously before her subjects. Dressed very simply in deep mourning, her fair hair and clear complexion came out the more effectively for their black surroundings. With visible emotion, and with her face bathed in tears, she listened to the reading of the Proclamation, supported by Lord Melbourne on the one side, and by Lord Lansdowne on the other, both dressed in court costume; while close at hand was the Duchess of Kent. The court-yard of the Palace was filled with a brilliant assemblage of high functionaries, consisting of Garter King-at-Arms, heralds and pursuivants, officers-of-arms on horseback, sergeants-at-arms, the sergeant-trumpeter, the Knights-Marshal and their men, the Duke of Norfolk as Earl-Marshal of England, and others—all clad in the picturesque dresses and wearing the insignia of their offices. At the conclusion of the Proclamation the Queen threw herself into the arms of her mother, and gave free vent to her feelings, while the band played the National Anthem, the Park and Tower guns discharged their salvos, and the spectators burst into repeated acclamations.

In some respects, the accession of Queen Victoria took place at a fortunate time. England was at peace with all foreign Powers; her colonies were undisturbed, with the exception of Canada, where some long-seated discontents were on the eve of breaking out into a rebellion which for a while proved formidable; and, about three years before, slavery had ceased in all British possessions. At home, several of the more difficult questions of politics and statecraft had been settled, either permanently or for a time, in the two preceding reigns; so that large sections of the people, formerly disloyal, or at least unfriendly to the existing order, were well disposed towards a form of government which no longer appeared in the light of an oppression. The repeal of the Test and Corporation Acts, in 1828, had conciliated the Dissenters; the removal of Roman Catholic disabilities, in 1829, had abolished one of the grievances of Ireland. By the Reform Bill of 1832—the temporary defeat of which had very nearly plunged the country into revolution—the middle classes had obtained a considerable accession of political power. The sanguinary rigour of the criminal laws had been partially mitigated; and, in September, 1835, an Act was passed for reforming the government of municipal corporations. The great Constitutional question, touching on the relation of the sovereign towards the Cabinet, had been virtually settled, during the same year, in harmony with those Parliamentary claims which were at any rate in accordance with the current of popular feeling. France—the great hotbed of revolution—was comparatively tranquil; and nothing in the general state of the world betokened the advent of any serious troubles.

Lord Melbourne, who held the office of Prime Minister at the time of the Queen’s accession, was an easy-tempered man of the world, well versed in political affairs, but possessed of little power as a speaker, and distinguished rather for tact than high statesmanship. He had entered public life in 1805 as an adherent of Charles James Fox, and therefore as a Whig of the most pronounced type; it was as leader of the Whigs that he now held power; but in the latter part of the reign of George IV. he had taken office under the Conservative Administrations of Mr. Canning, Lord Goderich, and the Duke of Wellington. In truth, he cared more for government than for legislation, and was therefore well disposed to join any set of politicians who seemed capable of conducting the affairs of the country with firmness and sense. Still, his most natural and permanent inclinations were towards a moderate Whiggism, very different, however, from the quasi-Radicalism of Fox, which he had adopted in the days of his youth. In 1830 he accepted the seals of the Home Office in the Government of Earl Grey; and this brought him back to the old connection. On the retirement of Lord Grey, in July, 1834, he succeeded to the Premiership; but in the following November the King dismissed the Ministry without any reference to the wishes of Parliament, and placed the Government in the hands of Sir Robert Peel. This was the occasion of that Constitutional struggle which, in consequence of the House of Commons gaining the day, has fixed the later practice in accordance with what are usually regarded as popular principles. Sir Robert Peel encountered so much opposition that, in April, 1835, he was compelled to resign, and Lord Melbourne for the second time became First Lord of the Treasury.

It was from this versatile, well-informed, but not very profound statesman that her Majesty received her first practical instructions in the theory and working of the British Constitution. That Lord Melbourne discharged his office with ability, devotion, and conscientiousness, is generally admitted; but it may be questioned whether he did not, however unintentionally, give something of a party bias to her Majesty’s conceptions of policy, and whether his teachings did not too much depress the regal power in England. It is in truth only within the present reign that it has come to be a fixed principle in English affairs that the Ministers for the time being are to be chosen from the majority of the

LORD MELBOURNE.

House of Commons, without the least regard to the sovereign’s desires. Melbourne himself, as we have seen, suffered from William’s assertion of his independence in the matter of choosing his Ministers; and it was perhaps not unnatural that he should wish to establish a contrary practice, by instilling into the mind of his illustrious pupil the conviction that absolute submission to the Parliamentary majority (or rather to the majority in the Lower House) was the only Constitutional course. But in fact that very course was an innovation; and to Lord Melbourne, more than to any other man, is the innovation attributable. There had undoubtedly been a movement in this direction since the latter end of the seventeenth century; but it had been occasional rather

PROCLAMATION OF THE QUEEN AT ST. JAMES’S PALACE. (See p. 22.)

than continuous, and was frequently checked by reactions towards the other practice.

From an early date in the Middle Ages, the King of England was assisted in the task of governing by the Privy Council, the members of which body did not, at the utmost, much exceed twelve. All were appointed by the sovereign, and each was removable at his pleasure. In process of time, the number of councillors became so great that their capacity for the despatch of business was seriously impaired; and in 1679 Charles II. limited the assembly to thirty members, of whom fifteen were to be the principal officers of State. Those functionaries had already assumed, under the name of the “Cabinet,” a species of separate existence, though only as a part of the larger body to which they belonged. It was not until shortly after the Restoration that this interior council acquired much importance; and by many it was regarded as unconstitutional and dangerous. Even at the present day, the Cabinet, in the striking language of Macaulay, “still continues to be altogether unknown to the law: the names of the noblemen and gentlemen who compose it are never officially announced to the public; no record is kept of its meetings and resolutions, nor has its existence ever been recognised by any Act of Parliament.”5 Nevertheless, the Cabinet, having gained a place in the machinery of the State, gradually drew to itself greater powers; and when, in 1693, the Earl of Sunderland persuaded William III. to choose his Ministers from among the members of the predominant party in the House of Commons, it is obvious that both the Legislature and the Government obtained increased importance. Yet the King still allowed himself considerable latitude, and had certainly no intention of giving up all power in the matter.

The eighteenth century was mainly divided between the laxity of the first two Georges—who, as foreigners largely concerned in Continental affairs, were glad to leave much to their Ministers, especially to so powerful a man as Sir Robert Walpole, though their powers of initiative were not entirely abandoned—and the high-prerogative ideas of the third George, who conceived that the kingly office had been unduly lowered since the Revolution of 1688, and who resented the supremacy of a few Whig families. Whatever may be thought of his policy or his motives, it cannot be denied that George III. was within his right in determining to have an actual voice in the appointment of his Ministers. A legal authority says:—“The Cabinet Council, as it is called, consists of those Ministers of State who are more immediately honoured with his Majesty’s confidence, and who are summoned to consult upon the important and arduous discharge of the executive authority. Their number and selection depend only upon the King’s pleasure; and each member of that Council receives a summons or message for every attendance.” Such is the statement of Mr. Edward Christian, Chief Justice of the Isle of Ely, and Downing Professor of the Laws of England in the University of Cambridge, in a note to the fourteenth edition of Blackstone’s Commentaries, published in 1803; and similar expositions appear in much more recent law-books. Originally, the Cabinet Council was a committee of the Privy Council: it is now, in effect, very little else than a committee of the House of Commons; and it was Lord Melbourne’s instructions to the young Queen which gave it finally, and perhaps irrevocably, that character.

Queen Victoria and her mother left Kensington on the 13th of July, and proceeded to Buckingham Palace, a residence which George IV. had favoured, and which William IV. detested and forsook. A levee was held shortly after her Majesty’s arrival; on which occasion the Queen is said to have presented a striking appearance, her head glittering with diamonds, and her breast covered with the insignia of the Garter and other orders. More important business, however, was approaching, and on the 17th of the month the Queen went in State to the House of Lords to dissolve Parliament. Addressing both Houses, her Majesty said:—“I have been anxious to seize the first opportunity of meeting you, in order that I might repeat in person my cordial thanks for your condolence upon the death of his late Majesty, and for the expression of attachment and affection with which you congratulated me upon my accession to the throne. I am very desirous of renewing the assurances of my determination to maintain the Protestant religion as established by law; to secure to all the free exercise of the rights of conscience; to protect the liberties, and to promote the welfare, of all classes of the community. I rejoice that, in ascending the throne, I find the country in amity with all foreign Powers; and, while I faithfully perform the engagements of the Crown, and carefully watch over the interests of my subjects, it will be the constant object of my solicitude to maintain the blessings of peace.” After alluding to the chief events of the session, the Queen concluded by observing:—“I ascend the throne with a deep sense of the responsibility which is imposed upon me; but I am supported by the consciousness of my own right intentions, and by my dependence upon the protection of Almighty God. It will be my care to strengthen our institutions, civil and ecclesiastical, by discreet improvement, wherever improvement is required, and to do all in my power to compose and allay animosity and discord. Acting upon these principles, I shall on all occasions look with confidence to the wisdom of Parliament and the affection of my people, which form the true support of the dignity of the Crown, and ensure the stability of the Constitution.”

In the course of this speech—which was delivered with great clearness and elocutionary power—the Queen expressed marked pleasure at a further mitigation of the criminal code, which she hailed as an auspicious commencement of her reign. The change was assuredly much needed, and the subject had engaged the attention of eminent statesmen and lawyers for several years. Jeremy Bentham had exposed the unreasonable and cruel severity of the punishments attached to comparatively trivial offences; and Sir Samuel Romilly, seconded by Sir James Mackintosh and Sir Fowell Buxton, had brought the state of the law before the notice of the Legislature. For a long while, the disinclination of Parliament to deal with important reforms kept this crying abuse of justice in the background; but in 1833 a Royal Commission was issued, for the purpose of inquiring how far it might be expedient to reduce the written and unwritten law of the country into one digest, and to report on the best manner of doing it. In the following year, the Commissioners were further required to state their opinions on the subject of the employment of counsel by prisoners, and on capital punishment. At the present day, it seems almost incredible that until 1836 the accused in criminal trials were not professionally defended. But still worse was the merciless spirit with which the rights of property were hedged about. A case is reported in which a poor Cornish woman, who, urged by want caused by the impressment of her husband as a seaman, had stolen a piece of cloth from a tradesman’s door, was hanged for the fact. Indeed, in the earlier years of the present century, the death-penalty was so frequent, and attached to so many offences, that numerous criminals were executed regularly every Monday morning outside Newgate. The extreme rigour of the law, however, was softened by various Acts of Parliament, passed from 1824 to 1829, with which the name of Sir Robert Peel is honourably associated. But much still remained to be done; and the Acts to which the Queen alluded, and which were introduced into the House of Commons by Lord John Russell, confined the punishment of death to high treason, and, with some exceptions, to offences consisting of, or aggravated by, violence to the person, or tending directly to endanger life. By the Criminal Law Consolidation Acts of 1861, death is now confined to treason and wilful murder; so that the reign of Queen Victoria has been distinguished, amongst other things, by a great and beneficent reform in the criminal laws of England.

The General Election followed quickly on the dissolution of Parliament, and the Whigs, who had been losing popularity for some time past, proceeded to the country with the questionable credit of being supported by Royal favour. Personally, the Queen liked Lord Melbourne, and readily adopted the political opinions he advanced. The Ministerialists made the most of the fact, and it was even said that they went about “placarded with her Majesty’s name.” But it is not improbable that this very circumstance told against them in many quarters, by inducing waverers to believe that the holders of office were endeavouring to influence the electorate after a manner entirely foreign to constitutional usage. At any rate, the Government lost seriously in the counties; yet, owing to their gains among the borough constituencies, and the large amount of support obtained in Scotland and Ireland, they returned to Westminster with a small majority, though with an appreciable loss of political repute. Parliament reassembled on the 20th of November, and on the 12th of December the Queen sent a message to the House of Commons asking for a suitable provision for the Duchess of Kent. This was made; the Civil List was settled, though not without some opposition from the economists; and the necessary preliminaries of a new reign were complete. The income of the Queen’s mother was fixed at

BANQUET TO THE QUEEN IN THE GUILDHALL (NOVEMBER 9, 1837). (See p. 31.)

£30,000, as against £22,000 previously; while the Civil List of her Majesty was settled at £385,000 a year, including £60,000 for the Privy Purse.

The Queen at once threw herself with business-like precision into the duties of her high office. She rose at eight, signed despatches until the breakfast hour, and then sent one of the servants to “invite” the Duchess of Kent to the Royal table. Such was the rather cold formality observed by the young monarch; and in other respects the etiquette of a Court seems to have been followed with rigid exactness. The Duchess never approached the Queen unless specially summoned, and always refrained from conversing on affairs of State. These restraints were considered necessary, in order to prevent any suspicion of undue influence by the mother over the daughter; but they were very distressing to the former. The late Mr. Charles C. F. Greville, for many years Clerk of the Council, was told by the Princess de Lieven that the Duchess of Kent was “overwhelmed with vexation and disappointment.” The same authority adds that the Queen behaved with kindness and attention to her parent, but she had rendered herself quite independent of the Duchess, who painfully felt her own insignificance. For eighteen years, she complained to Princess de Lieven, she had made her child the sole object of all her thoughts and hopes; and now she was taken from her. Speaking from his own observations, Mr. Greville remarks:—“In the midst of all her propriety of mind and conduct, the young Queen begins to exhibit slight signs of a peremptory disposition, and it is impossible not to suspect that, as she gains confidence, and as her character begins to develop, she will evince a strong will of her own.”6 With respect to the Queen and the Duchess, it should be recollected that one in the exalted position of the former is necessarily bound by other than domestic rules.

At twelve o’clock, the sovereign conferred with her Ministers, and the serious business of the day at once began. When a document was handed to her Majesty, she read it without comment until the end was reached, the Ministers in the meanwhile observing a profound silence. The interval between the termination of the Council and the dinner-hour was devoted to riding or walking, and the public had many opportunities of observing the admirable style in which the Queen sat her horse. At dinner, the first Lord-in-waiting took the head of the table, opposite to whom was the chief Equerry-in-waiting. The Queen sat half-way down on the right hand, and the guests were of course placed according to their respective ranks. At an early hour, her Majesty left the table for the drawing-room, where the time was passed in music and conversation. The sovereign herself was a proficient at the pianoforte, and often showed her abilities in this respect; and when the gentlemen returned from the dining-room (which was in about a quarter of an hour), a little singing would give variety to the evening. Mr. Greville speaks of these banquets as dull and formal. They were doubtless unavoidably so; for the ceremony of a Court is not favourable to the charm and vividness of the best social intercourse.

On the 9th of November—eleven days before the meeting of Parliament—the Queen went in State to the City, and was present at the inaugural banquet of the new Lord Mayor, Alderman Cowan. The streets through which her Majesty passed were densely thronged by people of all orders, who kept up an almost continual volley of cheers as the Royal carriages, with their escort, proceeded eastward. The houses were hung with richly-coloured cloths, green boughs, and such flowers as could be furnished by the mid-autumn season. Busts of Victoria were reared upon extemporary pedestals; flags and heraldic devices stretched across the streets; and London displayed as much festive adornment as was possible in those days. At Temple Bar, the Lord Mayor and Aldermen were seen mounted on artillery-horses from Woolwich, each with a soldier at its head, to restrain any erratic movement that might have troubled the composure of the City dignitaries. On the arrival of the Queen, the Lord Mayor dismounted, and, taking the City sword in his hand, delivered the keys to her Majesty, who at once returned them. Then the Lord Mayor resumed his horse, and, bearing the sword aloft, rode before the Queen into the heart of the City, the Aldermen following in the rear of the Royal carriage. In the open space before St. Paul’s Cathedral, hustings had been erected, on which were stationed the Liverymen of the City Companies, and the Christ Hospital (or Blue-coat) boys. One of the latter presented an address to the Queen, in accordance with ancient custom, and the whole of the boys then sang the National Anthem. The Guildhall was magnificently adorned for the occasion; and here an address was read by the Recorder. A sumptuous banquet followed, and at night the metropolis was very generally illuminated. On this occasion, the Queen was accompanied by the Duchesses of Kent, Gloucester, and Cambridge, and by the Dukes of Cambridge and Sussex, together with Prince George of Cambridge. The Ambassadors, Cabinet Ministers, and nobility, followed in a train of two hundred carriages, which are said to have extended for a mile and a half. The title of Baronet was conferred on the Lord Mayor, and the two Sheriffs were knighted. It was long since the City had had so brilliant a day, and the memory of it survived for many years.

The first great historical event in the reign of Queen Victoria was the insurrection in Canada. This proved to be of very serious import, and undoubtedly showed the existence of much disaffection on the part of the French-speaking colonists. It is probable that the latter had never outgrown the mortification of being snatched from their old association with the mother-country, and subjected to a Protestant kingdom. For several years after the Treaty of 1763, which made over Canada to Great Britain as a consequence of the brilliant victories gained by Wolfe and Amherst, the colony was despotically ruled; but in 1791 a more representative form of government was established, by which the whole possession was divided into an Upper and a Lower Province. Each of the provinces was furnished with a constitution, comprising a Governor, an Executive Council nominated by the Crown, a Legislative Council appointed for life in the same way, and a Representative Assembly elected for four years. This constitution (which had been sanctioned by an Act of the British Parliament) worked very badly, and in 1837 the Assemblies of both provinces were at issue with their Governors, and with the Councils appointed by the monarch. But by far the most serious state of affairs was that which prevailed in Lower (or Eastern) Canada, where the population was mainly of French origin, and where, consequently, the antagonism of race and of religion was chiefly to be expected. Towards the latter end of the reign of William IV., Commissioners were nominated to inquire into the alleged grievances, and the report of these gentlemen was presented to Parliament early in the session of 1837. On the 6th of March, Lord John Russell (then Home Secretary) brought the subject before the attention of the House of Commons, and, after many prolonged debates, a series of resolutions was passed, affirming the necessity of certain reforms in the political state of Canada. These reforms, however, did not go nearly far enough to satisfy the requirements of the disaffected, and by the close of 1837 the Canadians were in full revolt.

When the Queen opened her first Parliament, on the 20th of November, the state of Lower Canada was recommended, in the Royal Speech, to the “serious consideration” of the Legislature. Before any measures could be taken, intelligence of the outbreak reached England, and, on the 22nd of December, Lord John Russell informed the House of Commons that the Legislative Assembly of Lower Canada had been adjourned, on its refusal to entertain the supplies, or to proceed to business, in consequence of what were deemed the insufficient proposals of the Imperial Government. The colonists had undoubtedly some grievances of old standing, and their constitution required amendment in a popular sense. But a position had been assumed which the advisers of the Crown could not possibly tolerate, and the malcontents were now in arms against the just and legal authority of the sovereign. As early as March, Lord John Russell had said that, since the 31st of October, 1832, no provision had been made by the legislators of Lower Canada for defraying the charges of the administration of justice, or for the support of civil government in the province. The arrears amounted to a very large sum, which the House of Assembly refused to vote, while at the same time demanding an elected Legislative Council, and entire control over all branches of the Government.

The insurgents of Canada had numerous sympathisers in the United States, where, under cover of a good deal of extravagant talk about liberty, many people began to hope that existing complications would effect the long-desired annexation of the two provinces to the great Federal Republic. Those who were the most earnest in their views soon passed from sympathy into action. In the latter days of 1837, a party of Americans seized on Navy Island, a small piece of territory, situated in the river Niagara a little above the Falls, and belonging to Canada. Numbering as many as seven hundred, and having with them twenty pieces of cannon, these unauthorised volunteers seemed likely to prove formidable; but their means of offence were soon diminished by an energetic, though somewhat irregular, proceeding on the part of the Canadian authorities, acting, as was afterwards well known, under the orders of Sir Francis Head, the

PRESIDENT VAN BUREN.

Governor of Upper Canada. A small steamboat owned by the American invaders, with which they kept up communications with their own side of the river, and which was laden with arms and ammunition for the insurgents, was cut adrift from her moorings on the night of December 29th, set on fire, and left to sweep over the cataract. The affair led to a great deal of diplomatic correspondence between the American and British Governments; but the preceding violation of Canadian soil by a body of adventurers precluded the Cabinet of Washington from making any serious demands on that of London. Ultimately, in the course of 1838, the President (Mr. Van Buren) issued a proclamation calling on all persons engaged in schemes for invading Canada to desist from the same, on pain of such punishments as the law attached to the offence. This put an end to the difficulty so far as the two countries were concerned; but the insurrection was not yet entirely suppressed.

Although the worst disaffection was in Lower Canada, both provinces were disturbed by movements of a disloyal nature. Upper Canada was excited by the fiery appeals of a Scotsman named William Lyon Mackenzie; Lower Canada by the incitements of Louis Joseph Papineau, one of the disaffected French provincials. The two divisions of the colony, however, were jealous of each other, and this hampered what might otherwise have been a more dangerous rising. The Radical party in England supported the cause of the malcontents, and insisted on the necessity of at once redressing all grievances. The Government of Lord Melbourne maintained that the rebellion must be first suppressed; and undoubtedly that was the only course consistent with Imperial authority. In the autumn of 1837, a small party of English troops was beaten at St. Denis; but another detachment was successful against the rebels, and the garrisons of the various cities, though extremely small, held their own against the rising tide of insurrection. Aided by the Royalists, the Government force under Sir John Colborne inflicted some severe blows on the enemy; yet the movement continued throughout the greater part of 1838. On the 16th of January in that year, however, the Earl of Durham had been appointed Governor-General of the five British colonies of North America, and Lord High Commissioner for the adjustment of the affairs of Canada. The liberal policy thus inaugurated, and the victories obtained over the rebels by Sir John Colborne, Sir Francis Head, and others, brought the revolt to an end before the close of the year, and the colony soon afterwards entered on a future of prosperity.

The task of Lord Durham had, nevertheless, been surrounded by many difficulties, and, although he was sent by the British Government to carry out measures of leniency and concession, which his personal inclinations were well inclined to second, he was speedily called to account by the Imperial Cabinet for an ordinance touching the punishment of offenders, which, being regarded as in some respects illegal, was disallowed. Protesting that he had been abandoned by the Government, Lord Durham resigned on the 9th of October, and the principal conduct of affairs was left in the hands of Sir John Colborne. The policy of the High Commissioner had been swayed by truly benevolent and broadly liberal motives; but he had adopted—perhaps necessarily, considering the state of affairs with which he had to deal—a highly dictatorial manner, and the Opposition at home (especially in the Upper House, under the violent incentives of Lord Brougham) found several opportunities of effective attack. The Government, being weak and vacillating, said less in defence of their representative than they might have done; Lord Durham, in his passionate and imperious way, issued a farewell proclamation to the people of Canada, which, in effect, amounted to an appeal from the decisions of the Queen’s advisers—an appeal, that is, to a community still in rebellion against the Crown; Ministers replied by recalling their insubordinate servant; and the career of Lord Durham was at an end. Having left his post without permission—certainly a very improper proceeding—he was not honoured with the usual salute on landing, and, in revenge, caused his wife to withdraw from the position she held in the Queen’s household.

The recall of Lord Durham had been anticipated by his resignation; but the disgraced official, assisted by his two secretaries, Charles Buller and Edward Gibbon Wakefield, drew up a report containing the germs of that system of unity and self-government under which Canada has since become a loyal, contented, and progressive colony. It was not long before the Cabinet of Lord Melbourne carried out the suggestions of the discredited, but still successful, dictator. In 1839, Lord Glenelg, who had been Colonial Secretary during the dissension with Lord Durham, gave place to Lord Normanby, and he shortly afterwards to Lord John Russell, who in 1840 passed a measure for reuniting Upper and Lower Canada, and establishing a system of colonial freedom. In the same year, Lord Durham died at the early age of forty-eight; but the principles of his colonial policy rose triumphant above his tomb.