Читать книгу The Life and Times of Queen Victoria (Vol. 1-4) - Robert Thomas Wilson - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

CHAPTER IV.

COURTSHIP AND MARRIAGE.

ОглавлениеTable of Contents

English Chartism in the Summer of 1839—Riots in Birmingham—Principal Leaders of the Chartist Party—Excesses of the Artisans in Various Parts of Great Britain and Ireland—Chartist Rising at Newport, Monmouthshire—Conviction of Frost, Williams, and Jones—The Queen and Prince Albert—Early Life of the Prince—His Engaging Qualities—Desire of King Leopold to Effect a Matrimonial Engagement between Prince Albert and the Princess Victoria—First Visit of the Former to England—His Studies in Germany—Informal Understanding between Prince Albert and Queen Victoria—Difficulties of the Case—The Prince’s View of the Matter in the Autumn of 1839—Second Visit to England, and Formal Betrothal—Letter of Baron Stockmar on the Subject—Announcement of the Royal Marriage to the Privy Council and to Parliament—The Appointment of the Prince’s Household—Subjects of Difficulty and Dissension—Question of the Prince’s Religion—Reduction of his Annuity by a Vote of the House of Commons—Progress from Gotha to England, and Reception at Buckingham Palace—Marriage of Prince Albert to the Queen at the Chapel Royal, St. James’s.

An event of peculiar interest to her Majesty, and almost equally to the nation at large, took place in the second half of 1839; but, before relating the circumstances attending the Queen’s engagement to Prince Albert, it will be desirable to pass in rapid review the state of the country at that period—a state which might well have persuaded a young female sovereign of the need of sharing her responsibilities with one of the stronger sex. The Government, as we have seen, was extremely weak; Ireland, as usual, was giving the utmost trouble; the Colonies were agitated; and England itself was almost on the brink of revolution, owing to the distress existing among the labouring classes, and the incitements of the Chartists. The last of these dangers was the greatest of all. Hunger was preaching insurrection to thousands and tens of thousands of the poor and humble all over the kingdom; some few designing men, and scores of others who, however mistaken in their methods, were sincere and even noble in their aims, were thrusting the pike and the torch into the hands of maddened operatives; and the authorities, for a time, seemed paralysed. On the 14th of June, Mr. Attwood, Member for Birmingham, presented to the House a Chartist petition, signed, it was said, by 1,280,000 persons, and adopted at five hundred public meetings. It was at any rate sufficiently heavy to task the strength of twelve men to carry it out of the House; yet when Mr. Attwood, on the 12th of July, brought forward a motion to submit the grievances described in the petition to a select committee, he could obtain only forty-six votes, against 235 on the adverse side. On the 4th of July, a Chartist riot broke out in Birmingham, during which some policemen, sent from London, were severely handled. It was found necessary to call out the military, and for a time the disturbance seemed at an end. But on the 15th of the same month a much worse rising filled the whole town with consternation. Shops were sacked, houses set on fire in several localities, and the firemen obstructed and menaced in their attempts to extinguish the flames. Property was destroyed to the amount of nearly £50,000, and the vicinity which suffered most was afterwards described by the Duke of Wellington as presenting a worse appearance than that of a city taken by storm.

It was believed by superficial thinkers that these excesses would prove the death of Chartism; and, under this impression, the Attorney-General, Sir John Campbell, afterwards Lord Chief Justice of England, made a speech at a public dinner at Edinburgh on the 24th of October. He even spoke of Chartism as a thing already extinguished, and considered that the punishment of the rioters had brought the whole matter to an end. But the movement was served by some men of zeal, earnestness, and intellectual capacity, and it had aroused the deepest feelings of countless men and women who had no voice in the government of the country, and who undoubtedly suffered in divers ways. One of the principal leaders of the party, but by no means one of the wisest, was the Irishman, Feargus O’Connor—an agitator by taste and profession, who nevertheless claimed to be descended from the old kings of Ireland. There were others who said that he was the grandson of one Conyers, an Essex farmer who settled in the sister island, and whose son thought it prudent to Hibernicise his name. If so, the redoubtable Feargus was not so Irish as he seemed; but, however this may have been, he preferred to throw himself into the vortex of English agitation, leaving the Irish work to O’Connell. More reasonable, more argumentative, and more profoundly sincere, were Thomas Cooper, a poet of some power and passion; Henry Vincent, an effective lecturer; and Ernest Jones, a writer for the periodical press. These were all men of decided ability; and their advocacy of Chartist principles gave a more solid character to what might otherwise have passed off in effervescence.

On the other hand, it is not to be denied that the working classes, maddened by sufferings which their ignorance often led them to impute to wrong causes, committed many deplorable and guilty actions. At the direct incentive of the Trades-Unions, the factory hands sent threatening letters to the masters, fired the mills, made murderous attacks on such of their fellow-workmen as were willing to serve for lower wages, destroyed valuable machinery, and kept a large part of England, Scotland, and Ireland in perpetual terror. Chartism, by its assertion of political principles, whether right or wrong, did a certain amount of good, by giving another direction to all this turbulent socialism. Yet Chartism itself had its excesses, and, after the riots at Birmingham and elsewhere, the Government became alarmed. There were physical-force Chartists as well as moral-force Chartists; and at first the former were the more prevailing. The manufacturing districts were almost in a state of rebellion when, in the autumn of 1839, Henry Vincent was imprisoned at Newport, Monmouthshire, for delivering seditious speeches. There was at that time in Newport a respectable tradesman named John Frost, who had until recently been a magistrate of the borough, but whose use of intemperate language at a public meeting had caused his removal from the post. This dangerous egotist, or enthusiast, whichever he may have been, determined on making a bold attempt to rescue Vincent. He collected a vast body of armed men, marched seven thousand into the town on the 4th of November, while a great many more remained on the surrounding hills, and proceeded to the Westgate Hotel, where the magistrates were sitting.

The authorities knew something of what was about to happen, and had made as much preparation as they could. Thirty soldiers and some special constables were assembled in the building, and made a good defence. Frost’s men fired into the hotel, and wounded the Mayor, Mr. Phillips, together with several others. The soldiers returned the fire, killed and wounded a good many, and struck such terror into the rest that, with the want of spirit usually displayed by English mobs, they fled in confusion, notwithstanding their immense superiority in numbers. Frost was soon arrested, together with two other ringleaders, named Williams and Jones, and some of their followers. They were tried in January, 1840, on a charge of high treason, it being evident that, over and above the rescue of Vincent, the conspirators intended to form a junction with the malcontents of Birmingham and other large manufacturing towns, and thus create a general rising. The three leaders were found guilty, and sentenced to death; but, owing to some informality in the proceedings, this was afterwards commuted to transportation for life, and even the milder punishment was subsequently curtailed. An amnesty having been granted to Frost, Williams, and Jones, on the 3rd of May, 1856, they returned to England in the September of that year, to find everything wonderfully altered since they left. Other Chartist risings took place in the latter part of 1839 and the beginning of 1840, or were nipped in the bud by the vigilance of the authorities. The country was in a state of seething discontent, and it says much for the mingled leniency and firmness of the Government that the army was not called upon to suppress an insurrection.

While the working classes of Great Britain were thus starving and conspiring, and while the aristocracy (in the late summer of 1839) were amusing themselves with the theatrical jousts of the Eglintoun Tournament, her Majesty was advancing towards the most important event of her personal life. Her affection for her cousin, Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, dated back some years; but it was not until 1839 that a matrimonial alliance was effected. The Prince was the second son of Duke Ernest I. of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld (brother of the Duchess of Kent), and of his wife, the Princess Louise, daughter of the Duke of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg. He was born at the Rosenau (a summer residence of his father, situated about four miles from Coburg) on the 26th of August, 1819. The future husband of the Queen was thus about a quarter of a year younger than herself; and at the time of the formal engagement he was but a youth of twenty. From his childhood he had given proof of an excellent disposition, and, as he gained in years, he became extremely intelligent and studious. It is easy to flatter a Prince, and many tongues are always ready to perform the task. But it seems to be the absolute truth to say of Prince Albert that his nature was manly, sincere, and affectionate; that his life was blameless and discreet; and that his intellect and acquirements were remarkable, even at an early age. Added to this, he was graced with physical beauty and pleasing manners; so that in more ways than one he attracted the attention of many observers.

When, in 1836, it became evident that the Princess Victoria must, in all human probability, succeed to the British throne, her uncle, King Leopold, was very desirous of effecting a marriage between his niece and his nephew. He well knew how terrible would be the weight of Imperial sovereignty on the head of a young, inexperienced girl, and he wished to lighten the burden by the constant advice and guidance of a conscientious husband. On this subject lie consulted with his valued friend and private adviser, Baron von Stockmar, a man of great judgment and experience, and of a proportionate honesty and independence. Stockmar thought well of the young Prince, but would not commit himself to a positive opinion until he had seen more of him. A visit to Kensington Palace was subsequently arranged with the Duchess of Kent, and Prince Albert came to England, with his father and brother, in May, 1836. This was his first acquaintance with the country which he was afterwards to regard as almost his own; and it laid the foundations of the subsequent union. The Prince, it was obvious, had made a very favourable impression on the Princess. How far the former was affected could not as yet be ascertained; but he knew that the marriage was considered desirable, and he must of necessity have been flattered by the possibility of such a future. About the same period, King Leopold made his niece aware of his wishes on the subject, and the answer of the Princess showed that his hopes were also her own.

During the next few years, Prince Albert pursued his studies in Germany,

PRINCE ALBERT.

chiefly at the University of Bonn. After keeping three terms there, and earning the highest praises from the several professors, he left in September, 1838, and in the ensuing months paid visits to Switzerland and Italy. Returning to his own country in the early summer of 1839, he was formally declared of age a little before the completion of his twentieth year. The Prince had all along continued to take a great interest in his cousin, and many were the rumours, both in Germany and England, that he was her affianced husband. But the statement was premature, for nothing had been settled as yet. Still, though there was no formal engagement, it came to be gradually understood that the English Queen and the young Saxon Prince stood in a certain relation of mutual fidelity, though not of an absolutely binding order. William IV. had always been greatly opposed to the contemplated match, and formed various schemes for his niece’s marriage, the most favoured of which had Prince Alexander of the Netherlands for its object. But there was now no hindrance in the way of the Queen’s wishes, and everything conspired towards one result. The Dowager Queen Adelaide subsequently told her illustrious relative that the King would never have attempted to influence his niece’s affections, had he known they were bestowed in any particular quarter. Yet a disagreeable impression had been produced, which could not be entirely obliterated at a later period.

Attached as she was to the Prince, the Queen desired to postpone the marriage for a few years, partly because of her cousin’s extreme youth. The visit of Albert to Windsor Castle in October, 1839, however, decided the matter. It was indeed the desire and intention of the Prince himself to come to a definite understanding on the question. He considered, not unreasonably, that if he was to keep himself free, and to decline any other career which might seem likely, he ought to have some positive assurance that the engagement, of which so much had been said, would really be carried out. He even admitted in after life that he was not without some fear lest the Queen should be playing on his feelings. It must be recollected, however, that the position of her Majesty, as a sovereign, from whom the first advances must proceed, and yet as a woman, from whom a certain reserve is expected, was one of great difficulty. In the autumn of 1839, the Prince had resolved to declare himself free, if further postponement were required; but the course of events made it quite unnecessary that he should speak to any such effect. Her Majesty was unable to resist the combined force of the young Prince’s good looks and fascinating manners. All previous hesitation disappeared, and, on the 14th of October, she informed Lord Melbourne of her intention. The Premier, we are told, showed the greatest satisfaction at the announcement, adding the expression of his conviction that it would not only make the Queen’s position more comfortable, but would be well received by the country, which was anxious for her marriage.8 “A woman,” he observed, “cannot stand alone for any time, in whatever position she may be.” On the following day, an understanding was come to between the parties chiefly concerned, and all that remained was the execution of the formal arrangements. A month later (November 14th), the Prince and his elder brother left London for Wiesbaden, where they found the King of the Belgians and Baron Stockmar awaiting them. This was a time of great letter-writing, and a communication from Stockmar to the Baroness Lehzen (one of the governesses of the Princess Victoria), dated December 15th, 1839, is particularly noticeable.

“With sincere pleasure,” writes the Baron, “I assure you, the more I see of the Prince, the better I esteem and like him. His intellect is so sound and clear, his nature so unspoiled, so childlike, so predisposed to goodness as well as truth, that only two external elements will be required to make of him a truly distinguished Prince. The first of these will be the opportunity to acquire a proper knowledge of men and of the world; the second will be intercourse with Englishmen of experience, culture, and integrity, by whom he may be made thoroughly conversant with their nation and constitution.... As regards his future relation to the Queen, I have a confident hope that they will make each other happy by mutual love, confidence, and esteem. As I have known the Queen, she was always quick and acute in her perceptions; straightforward, moreover, of singular purity of heart, without a trace of vanity or pretension. She will consequently do full justice to the Prince’s head and heart; and, if this be so, and the Prince be really loved by the Queen, and recognised for what he is, then his position will be right in the main, especially if he manage at the same time to secure the good will of the nation. Of course he will have storms to encounter, and disagreeables, like other people, especially those of exalted rank. But, if he really possess the love of the Queen and the respect of the nation, I will answer for it, that after every storm he will come safely into port. You will therefore have my entire approval, if you think the best course is, to leave him to his own clear head, his sound feeling, and excellent disposition.”

It was the original intention of the Queen to make the first notification of her contemplated marriage to Parliament; but she afterwards considered that the Privy Council was the fittest body for the purpose. The Council met on the 23rd of November at Buckingham Palace—an unusually large assemblage of eighty-three members. Wearing a bracelet with the Prince’s portrait—which, as she subsequently recorded in her Journal, “seemed to give her courage”—her Majesty read to the Council a declaration of her intention to contract a union, of which she declared her belief that it would at once secure her domestic felicity, and serve the interests of her country. Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha was indicated as the object of her choice; and the declaration concluded with the words:—“I have thought fit to make this resolution known to you at the earliest period, in order that you may be apprised of a matter so highly important to me and to my kingdom, and which, I persuade myself, will be most acceptable to all my loving subjects.” When the Queen had finished reading, Lord Lansdowne rose, and asked, in the name of the Council, that her Majesty’s welcome communication might be printed. Leave was given, and the declaration was published in the next Gazette, whence it was copied into the newspapers. Some intelligence of the statement to be made to the Privy Council had found its way into the public mind; and, on leaving the Palace, her Majesty was cheered with more than usual warmth.

The announcement to the Legislature was made in the Queen’s Speech at the opening of the next session, January 16th, 1840. At the same time, her Majesty expressed her conviction that Parliament would provide for such an establishment as might appear suitable to the rank of the Prince and the dignity of the Crown. In the meanwhile, some difficulties had arisen with regard to various matters of detail. The settlement of the Prince’s household was no very easy business. With admirable sense, Albert wrote to her Majesty on the

THE MARQUIS OF LANSDOWNE.

10th of December, 1839:—“I should wish particularly that the selection should be made without regard to politics, for, if I am really to keep myself free from all parties, my people must not belong exclusively to one side. Above all, these appointments should not be mere ‘party rewards,’ but they should possess some other recommendation, besides that of political connection. Let the men be either of very high rank, or very accomplished, or very clever, or persons who have performed important services for England. It is very necessary they should be chosen from both sides—the same number of Whigs as of Tories; and, above all, it is my wish that they should be men well educated and of high character, who, as I have said, shall have already distinguished themselves in their several

INTERIOR OF THE CHAPEL ROYAL, ST. JAMES’S.

positions, whether it be in the army or navy, or the scientific world. I am satisfied you will look upon this matter precisely as I do, and I shall be much pleased if you will communicate what I have said to Lord Melbourne, so that he may be fully aware of my views.”

These most reasonable suggestions were disregarded, and, without any consultation of the Prince’s wishes on a matter which closely concerned himself, the post of Private Secretary was conferred on Mr. Anson, who had long discharged the same functions for the Premier. This was evidently another attempt of the Whig Ministry to obtain a permanent influence over the Palace. Prince Albert protested against the appointment, only to be told that the matter had gone too far for withdrawal. Fortunately, however, Mr. Anson showed, in the discharge of his duties, an entire absence of party predilections, together with many positive qualities which won the high esteem of the Prince. A question much debated at the time was as to whether the Queen’s husband should be made a peer of the realm, as had been done in the case of Queen Anne’s consort, Prince George of Denmark; but Prince Albert himself resisted the suggestion, which was certainly one of very questionable wisdom. The consideration of precedence was also a knotty point. The Queen desired that her husband should take precedence immediately after herself; but her uncle, the King of Hanover, refused to waive his right, and the Duke of Wellington, speaking on behalf of the Tory peers, declined to consent. The question was afterwards withdrawn from the Naturalisation Bill to which it had been attached, and was settled by an exercise of the Royal Prerogative, which, as a species of compromise, both political parties accepted. By letters patent, issued on the 5th of March, 1840, it was provided that the Prince should thenceforth, “upon all occasions, and in all meetings, except when otherwise provided by Act of Parliament, have, hold, and enjoy, place, pre-eminence, and precedence next to her Majesty.”

There were worse subjects of dissension, however, than those already mentioned. No sooner was the announcement of the Royal marriage made public than sinister rumours arose that the Prince was a Roman Catholic. Others averred that he was an infidel. But the most damaging because the most definite charge was that of being a Papist; and this was strengthened by the singular and very careless omission of any reference to the Prince’s religion in the declaration to the Privy Council and to Parliament. King Leopold of Belgium saw the imprudence of giving the least opportunity for doubt or cavil; but Ministers would not or could not recognise the danger. Debates took place in both Houses in the discussion on the Address, and, in the House of Lords, the Duke of Wellington carried a motion for introducing the word “Protestant” into the Congratulatory Address to the Queen. It was on this occasion that Lord Brougham, referring to some observations of Lord Melbourne, made use of the memorable words:—“I may remark that my noble friend is mistaken as to the law. There is no prohibition as to marriage with a Catholic. It is only attended with a penalty, and that penalty is merely the forfeiture of the Crown.” The Protestantism of Prince Albert was in truth well known, and so was that of his family, with but few exceptions. In a letter to the Queen, dated December 7th, 1839, the Prince said:—“There has not been a single Catholic Princess introduced into the Coburg family since the appearance of Luther in 1521. Moreover, the Elector, Frederick the Wise of Saxony, was the very first Protestant [Protestant Prince?] that ever lived.” Still, it was remiss of the Government not to make the desired declaration, especially as some of the Prince’s relatives had become Romanists. People generally have but little historic knowledge; and indeed the subject was one which history did not much avail to settle.

While the Lords were raising a question as to the Protestantism of the Prince, and making difficulties in the matter of precedency, the Commons were considering the position of the new-comer from a financial point of view. On the 24th of January, 1840, Lord John Russell moved “that her Majesty be enabled to grant an annual sum of £50,000 out of the Consolidated Fund for a provision to Prince Albert, to commence on the day of his marriage with her Majesty, and to continue during his life.” Three days after, Mr. Joseph Hume, faithful to his character as a guardian of the public purse, moved as an amendment that £21,000, instead of £50,000, be voted annually to Prince Albert. He would even have preferred that no grant whatever should be made to the Prince during her Majesty’s lifetime; but in this respect he had yielded to the wishes of his friends. Mr. Hume asked what was to be done with such a sum as the Government proposed to grant, and courteously remarked that Lord John Russell must know the danger of setting a young man down in London with so much money in his pockets. The amendment was lost by 305 votes against 38—a majority so enormous that it might well have discouraged any further opposition. Yet, on the very same evening, Colonel Sibthorp, a member of the Tory Opposition, moved that £30,000 should be the extent of the annuity, and, being supported by nearly all the Conservatives, as well as by the Radicals, and even some of the Whigs, he carried his proposal by 262 votes against 158. There was in truth a good deal to be said in favour of the smaller sum, though the suggestion roused Lord John Russell almost to fury, as if an actual personal affront to the Queen were intended. The country was in great distress; agriculture and manufactures were alike suffering; the poverty of large classes was extreme; taxation was oppressively heavy; and the revenue showed an ever-increasing deficit. Under these circumstances, the reduction of the annuity was essentially just and fair. The matter was decided on the 27th of January—the same day that the Government were so strenuously resisted in the House of Lords on the Precedency question as to see the necessity of separating it from the Naturalisation Bill. These circumstances induced in Prince Albert, for a short time, a fear lest his marriage to the Queen would not be popular with the English people; but he was soon undeceived on this point by the representations of his friends in England.

On the day following Colonel Sibthorp’s successful amendment with respect to the annuity, the Prince, accompanied by Lord Torrington and Colonel (afterwards General) Grey, who had been sent to invest him with the insignia of the Garter, and conduct him ceremoniously to England, set out from Gotha, accompanied by his father and brother. In the course of the journey, King Leopold was visited at Brussels, and the party then proceeded to Calais, where they were met by Lord Clarence Paget, commanding the Firebrand, in which the Prince and his companions were conveyed to the shores of Kent. They landed at Dover on the 6th of February, and met with a very hearty reception. This was repeated at Canterbury, and at every other place along the line of route,

COURTYARD OF ST. JAMES’S PALACE.

while at London the enthusiasm was marked and unmistakable. Buckingham Palace was reached on the afternoon of February 8th, when the Prince found her Majesty and the Duchess of Kent waiting at the door to greet him. In a little while, the Lord Chancellor administered the oath of naturalisation, and a banquet followed in the evening. The Prince was fairly settled in his new home.

The marriage was celebrated in the Chapel Royal, St. James’s, on the 10th of February, 1840. An unusually large crowd assembled in St. James’s Park and its approaches, notwithstanding the severity of the weather, which did not become sunny until after the return of the bridal party from the chapel. Prince Albert wore the uniform of a British Field Marshal, with the insignia of the Garter, the jewels of which had been presented to him by the Queen. On one side of the carriage sat the Prince’s father, on the other side his brother; both in uniform. A squadron of Life Guards formed the escort to the chapel, and the bridegroom was loudly cheered. Her Majesty soon afterwards

DUKE ERNEST, OF SAXE COBURG-GOTHA, PRINCE ALBERT’S BROTHER.

followed, with the Duchesses of Kent and Sutherland. She looked pale and anxious, but smiled every now and then at little incidents occurring among the crowd. The somewhat dusky old palace was brightened up for the occasion by temporary decorations, and still more by the presence of splendidly-dressed ladies, picturesque officials, gentlemen-at-arms, yeomen of the guard, heralds, pages, and cuirassiers. The altar of the Chapel Royal was set out with a great deal of gold plate, and four State chairs were provided for the Queen, Prince Albert, the Queen Dowager (Adelaide), and the Duchess of Kent. The ceremony was performed by the Archbishops of Canterbury and York, and the Bishop of London. All present admired the calm grace and dignified deportment of the Prince; but of course the great object of interest was the Queen herself. She looked excited and nervous, and, according to a letter from the Dowager Lady Lyttelton (one of the ladies-in-waiting), her eyes were swollen with tears, although great happiness appeared in her countenance. The Duchess of Kent is said to have been disconsolate and distressed; while the Duke of Sussex, who gave away the bride, was in the gayest spirits. The John Bull—a high Tory journal, edited by Theodore Hook, the motto of which was, “For God, the Sovereign, and the People!”—remarked that the Duke of Sussex was always ready to give away what did not belong to him. It should be understood that the sovereign whom Hook set up his paper to champion was George IV., and that therefore it was no great inconsistency to insult a Royal Duke who was also a Liberal, and the uncle of a Liberal monarch. The Royal Family, as we have seen, were not very popular with the Tories of that date. At the Queen’s marriage, only two Conservative peers were present: the Duke of Wellington and Lord Liverpool.9

As her Majesty was returning to Buckingham Palace, it was observed that the paleness and anxiety of the morning had given place to a bright flush, and a more unrestrained and joyous manner. After the wedding breakfast, the newly-married couple left for Windsor, on reaching which they found the whole town illuminated. A cordial reception from the residents, and from the Eton boys, sufficiently declared the sentiment of affectionate respect with which the Queen and Prince were regarded in the Royal Borough.

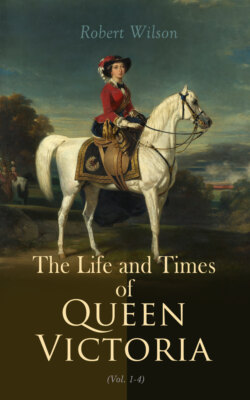

MARRIAGE OF QUEEN VICTORIA. (See p. 70.)

(After the Painting by Sir George Hayter, R.A.)