Читать книгу The Life and Times of Queen Victoria (Vol. 1-4) - Robert Thomas Wilson - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

CHAPTER III.

THE DIFFICULTIES OF A YOUNG SOVEREIGN.

ОглавлениеTable of Contents

Decline in the Popularity of the Queen—Its Causes—Her Majesty Accused of Encouraging the Papists—Alleged Design to Assassinate the Monarch—Disloyal Toryism—Honourable Conduct of the Queen—Fatal Riots at Canterbury, owing to the Pretensions of John Nicholls Thom—Preparations for the Coronation—The Ceremony at Westminster Abbey—Incidents of the Day—Mismanagement at Coronations—Development of Steam Navigation and the Railway System—Prorogation of Parliament in August, 1838—Difficult Position of the Government—Rise of Chartism—Appearance of Mr. Gladstone and Mr. Disraeli in the Political Arena—Failure of Mr. Disraeli’s First Speech—“Conservatives” and “Liberals”—Capture of Aden, in Southern Arabia—Wars with China, owing to the Smuggling of Opium into that Country by the Anglo-Indians—Troubles in Jamaica—Bill for Suspending the Constitution—Defeat and Resignation of the Melbourne Government—Ineffectual Attempt of Sir Robert Peel to Form a Cabinet—The Question of the Bedchamber Women—Reinstatement of the Melbourne Administration.

Nothing could exceed the popularity of the Queen at the beginning of her reign. Her youth, her innocence, the novelty of her duties and the difficulty of her position, all appealed with a commanding tenderness to every manly instinct and every womanly sympathy. But after a while a change occurred in the national sentiment, which was not altogether inexcusable on the part of the public, though it did some injustice to the sovereign. Many enthusiasts expected more than they had any right to expect, and were disappointed because the Queen did not at once do wonders for the removal of grievances, and the cure of national distress. Beyond these vague impressions, however, there were some real causes of complaint, or at least of apprehension. It was seen very clearly that the young monarch had placed herself too unreservedly in the hands of one political connection. The offices about the Queen’s person were filled by ladies belonging to the families of the chief Ministers. People said that Lord Melbourne was too much at the Palace; that he sought to occupy the position of a

THE EARL OF DURHAM.

Mentor in all things; and that in the General Election the Queen showed a partiality for certain candidates who belonged to the faction then in power. Ministers and their supporters did really use the name and supposed leanings of her Majesty as a means of bolstering up a Cabinet which they knew to be generally unpopular; and persons were found to ask whether the English Court was always to be the appendage of an aristocratic coterie.

Under the influence of these feelings, some men were unmanly enough to attack the Queen in public with shameful imputations. The excitement, which began during the elections of 1837, had become almost frantic in 1839. The Orangemen of Ireland, and the ultra-Protestants of England, believed, or affected to believe, that the sovereign was being influenced to destroy the reformed religion, and re-establish Papacy throughout her dominions. The Melbourne Administration supported religious liberty; to some extent, its members leant for support upon the Irish vote; the Queen favoured Lord Melbourne: therefore, her Majesty was inclined to Rome. Such were the stages by which these hot-headed reasoners

THE THRONE-ROOM, BUCKINGHAM PALACE.

arrived at their conclusion. Some placed their hopes in the Tory party; others openly declared that the Tories, could they only get possession of the sovereign, would poison her, and change the succession. Men recollected with an uneasy feeling that, in 1835, Mr. Joseph Hume, a conspicuous Radical member of Parliament, detected and unmasked an Orange plot for setting aside the rights of the Princess Victoria, and giving the crown to the Duke of Cumberland, on the ridiculous plea that, unless some such step were taken, the Duke of Wellington might seize the regal power for himself. The investigations which the Government were compelled to make raised a strong suspicion that the Duke of Cumberland was privy to this traitorous scheme. The English people were so delighted when he left for Hanover, after the death of William IV., that a cheap medal was struck to commemorate the event; and his despotic rule in the small German kingdom amply justified their fears. Nothing more, it would seem, was to be dreaded from the fifth son of George III.; yet apprehensions of a conspiracy still remained.

It is a remarkable feature of the times that during all this commotion the Liberals were the loyal and courtly party, while many of the Tories indulged in fierce invectives against the monarch. On the one side, the Irish agitator, Daniel O’Connell, vaunted in the course of 1839 that he could bring together five hundred thousand of his countrymen to defend the life and honour of “the beloved young lady” who filled the English throne; on the other, a Mr. Bradshaw, member for Canterbury in the Tory interest, alleged, without any circumlocution, that the countenance of Queen Victoria, the ruler of Protestant England, was given to “Irish Papists and Rapparees,” her Majesty, he added, being “Queen only of a faction, and as much of a partisan as the Lord Chancellor himself.” This, indeed, was by no means the worst of the speaker’s utterances; but his wildest flights of vituperation were received with enthusiastic cheers. It is but fair, however, to add that he afterwards apologised for his bad manners. At a meeting held at the Freemasons’ Tavern, presided over by Lord Stanhope, a Chartist orator proposed to open a subscription for presenting the Queen with a skipping-rope and a birch-rod. Other persons spoke with equal violence, and in some instances the authorities even found it necessary to warn military officers, and civil servants of the Crown, against such disloyal utterances. One very painful incident occurred towards the end of June, 1839, when her Majesty was hissed on Ascot racecourse. It was represented to her that the Duchess of Montrose and Lady Sarah Ingestre were amongst the persons so acting; the Queen therefore showed her displeasure to those ladies at a State ball. The slander was apparently traced to Lady Lichfield, who denied it, first by word, and then by writing. With the letter in her hand, the Duchess went to the Palace, and required an audience of her Majesty, but, after being kept waiting a couple of hours, was refused, on the advice of Lord Melbourne. She was extremely angry, and insisted that a written statement should be laid before the Queen. These circumstances increased the unpopularity of the monarch, and she was coldly received at the prorogation of Parliament.

Yet, if people could have set aside their prejudices and passions, they would have found abundant evidence that the nature of the Queen was instinct with just and honourable feelings. She had been accustomed from childhood to live strictly within her income, and to deny herself any little gratification which could not be at once paid for in ready money. The same habit of virtuous prudence continued after her accession to the throne; and out of her savings she was enabled, during her first year of regal power, to discharge the heavy debts of her father, contracted before she was born. With respect to this matter, however, it should be mentioned that, according to a statement in the Morning Post, the Duke of Kent’s executors had succeeded in Chancery in establishing their claim against the Crown to the mines of Cape Breton, which had been made over to his Royal Highness for a period of sixty years dating from 1826, and that therefore the Crown must either have paid the Duke’s debts, or suffered the mines to be worked for the benefit of the creditors. The Queen also paid her mother’s debts, which, however, were in some respects her own, since they had in the main been incurred on her behalf. With a truly liberal and generous feeling, she continued to the natural children of William IV. by Mrs. Jordan the allowance of £500 a year each which had been granted them by the King. What was really regrettable in the early part of the Queen’s reign was the completeness with which the new sovereign placed herself in the hands of Lord Melbourne and his clique, and which seemed for a time to set her in the light of a partisan. But what else could be expected of one so young, so inexperienced, so incapable by early training to assume all at once the full responsibilities of royalty? The fault was with the advisers, rather than with the advised.

The General Election of 1837 failed to rescue the Government from the difficult position they had long occupied. Threatened by the Radicals, who considered they did not move fast enough, they were obliged to lean for assistance on the Conservatives, without whose help they would often have been left in a minority. Ministers felt the ignominy of their lot, but were unable to amend it; and a painful set of incidents in the spring of 1838 gave occasion for a sharp attack on the Home Office. A few years previously, a person called John Nicholls Thom left his home in Cornwall, and settled in Kent, where he described himself as Sir William Courtenay, Knight of Malta. He was in truth a religious madman, claiming to be the King of Jerusalem, or, in other words, the Messiah; and multitudes of persons, belonging for the most part, though not entirely, to the poor and ignorant classes, believed in his assertions. Dressed in a fantastical costume, he went about the country, haranguing the people, and violently denouncing the Poor Law. He persuaded many of the farmers and yeomen that he was entitled to some of the finest estates in Kent, and that he would shortly be established as a great chieftain, when all the people on his lands should live rent-free. To the still more credulous he spoke of himself as Jesus Christ, and pointed in confirmation to certain marks in his hands and side, which he described as the wounds inflicted by the nails of the cross. Crowds followed him about, believing in his foolish miracles; some actually paid him divine honours; but a tragedy was approaching. On the 31st of May, 1838, Thom shot a constable who had interfered in his proceedings. The military were then summoned from Canterbury, when the rioters retreated into Bossenden Wood; a lieutenant who endeavoured to arrest the maniac was also shot dead; and a riot ensued, in which several persons, including Thom himself, were killed by the fire of the soldiers, and others wounded. It afterwards appeared that the man had previously been confined as a lunatic, but had been liberated the year before by Lord John Russell, acting as Home Secretary. For this, the latter was severely censured by the Opposition in Parliament, and a select committee was appointed to inquire into the circumstances; but it was generally agreed that the Minister was not to blame in the matter.

In the first half of 1838, attention was drawn away from many distracting controversies by the preparations for crowning the new sovereign. The

THE CORONATION CHAIR, WESTMINSTER ABBEY.

imagination of the populace was powerfully affected by the thought of this gorgeous ceremony, and a Radical paper of the time observed that the commonalty had gone “coronation-mad.” Political economists, however, fixed their thoughts upon the question of expense, and it was resolved that the charges should fall far short of those incurred for George IV., which amounted to £243,000. The crowning of his successor had cost the nation no more than £50,000; but it was stated in Parliament that the expenses for Victoria would be about £70,000—an increase on the previous reign due to the desire of Ministers to enable the great

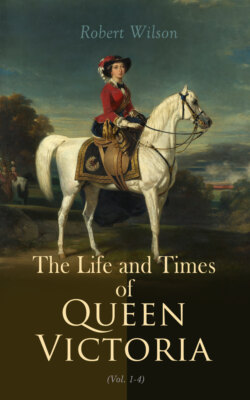

THE CORONATION OF THE QUEEN. (After the Painting by Sir George Hayter.) (See p. 43.)

mass of the people to share in what was described as a national festivity. Some important alterations were introduced into the programme. The procession of the estates of the realm was to be struck out, and the accustomed banquet in Westminster Hall, with its feudal observances, was likewise marked for omission. To compensate for these losses, it was arranged that there should be a procession through the streets which all could see. The new arrangements were objected to by some of the upper classes; but there can be no question that the popularity of the show was greatly enhanced by these concessions to the wishes of the majority.

The coronation took place on the 28th of June. Although the day began with clouds and some rain, the weather afterwards cleared, and the pageantry was seen to great advantage. The streets were lined with spectators; an unbroken row of carriages moved on towards the Abbey; and the windows were crowded with on-lookers. At ten o’clock A.M., the Royal procession started from Buckingham Palace, and, passing up Constitution Hill, proceeded along Piccadilly, St. James’s Street, Pall Mall, Cockspur Street, Charing Cross, Whitehall, and Parliament Street, to the west door of the grand old historic structure where the ceremonial was to take place. The carriages of the Ambassadors Extraordinary attracted much attention, especially that of Marshal Soult, which, so far as the framework was concerned, appears to have been the same as that used on occasions of state by the last great Prince of the House of Condé, one of the most famous military commanders of the seventeenth century. The gallant adversary of Wellington in the wars of the Peninsula was everywhere received with the heartiest cheers, and was so deeply touched by this cordiality of feeling on the part of his old opponents, that some years after he declared himself, in the French Chamber, a warm partisan of the English alliance. Westminster Abbey had been brilliantly decorated for the occasion. The ancient aisles glowed and shone with crimson and purple hangings, with cloth of gold, and with the jewels, velvets, and plumes of the peeresses; and when the procession entered at the west door, the effect was both magnificent and solemn.

It was half-past eleven when her Majesty reached the Abbey. Retiring for a space into the robing-room, she issued forth clad in the Royal robes of crimson velvet, lined with ermine, and embroidered with gold lace. Round her neck she wore the collars of the Garter, Thistle, Bath, and St. Patrick, and on her head a circlet of gold. It is mentioned that she looked very animated; and assuredly the scene was one well calculated to impress even the mind of a sovereign with a sense of lofty and almost overwhelming grandeur. The noble, time-honoured building, with half the history of England in its monuments and its memories, appealed powerfully to the moral sentiment; while the splendour of the decorations and the costumes was such as to hold the Turkish Ambassador entranced for some minutes. The peers and great officials, with their pages and other attendants, were gorgeously dressed; so also were the Foreign Ministers and their suites, and, in particular, Prince Esterhazy glittered with diamonds to his very boot-heels. Her train upborne by the daughters of eight peers, preceded by the regalia, the Princes of the blood-royal, and the great officers of State, and followed by the ladies of the Court and the gentlemen-at-arms, the Queen advanced slowly to the centre of the choir, and, amidst the chanting of anthems, moved towards a chair placed midway between the chair of homage and the altar, where, kneeling on a faldstool, she engaged in private devotion. The ceremony of the coronation then commenced.

The first act was that which is called “the Recognition.” Accompanied by some of the chief civil dignitaries, the Archbishop of Canterbury advanced, and said, “Sirs, I here present unto you Queen Victoria, the undoubted Queen of this realm; wherefore, all you who are come this day to do your homage, are you willing to do the same?” The question was answered by loud cries of “God save Queen Victoria!” and, after some further observances, her Majesty made her offerings to the Church, in the shape of a golden altar-cloth, and an ingot of gold of a pound weight. The strictly religious part of the ceremony followed, and, at the conclusion of a sermon preached by the Bishop of London, the Oath was administered in the manner usual on such occasions. The Queen then knelt again upon the faldstool, while the choir sang, “Veni, Creator Spiritus;” after which came the Anointing. Her Majesty seated herself in the historic chair of King Edward I., while the Dukes of Buccleuch and Rutland, and the Marquises of Anglesey and Exeter (all being Knights of the Garter), held a cloth of gold over her head. The Dean of Westminster next took the ampulla from the altar, and poured some of the oil into the anointing-spoon; whereupon the Archbishop anointed the head and hands of the Queen, marking them with the cross, and pronouncing the words,—“Be thou anointed with holy oil, as kings, priests, and prophets were anointed,” etc. A prayer or blessing was then uttered, and the investiture with the Royal Robe, the rendering of the Orb, and the delivery of the Ring and Sceptre, were the next ceremonies. The placing of the Crown on the sovereign’s head was one of the most striking incidents of the day. As the Queen knelt, and the crown was placed on her brow, a ray of sunlight fell on her face, and, being reflected from the diamonds, made a kind of halo round her head.7 At the same moment, the peers assumed their coronets, the Bishops their caps, and the Kings-of-Arms their crowns, thus adding greatly to the richness and dignity of the spectacle. Loud cheers were echoed from every part of the Abbey; trumpets sounded, drums beat; and the Tower and Park guns were fired by signal.

The Benediction, the Enthroning, and the formal rendering of Homage, now ensued. The last of these ceremonies had a singularly feudal character. First, the Archbishop of Canterbury knelt, and did homage for himself and the other Lords Spiritual; then the uncles of the Queen, the Dukes of Sussex and Cambridge, removed their coronets, and, without kneeling, made a vow of fealty in these words:—“I do become your liege man, of life and limb, and of earthly worship; and faith and truth I will bear unto you, to live and die, against all manner of folks. So help me God!” Having touched the crown on the Queen’s head, they kissed her left cheek, and retired. The other peers then performed their homage kneeling, the senior of each rank pronouncing the words. It was at this part of the day’s proceedings that an awkward incident occurred—an incident, however, which served to bring out an amiable trait in the sovereign’s character. As Lord Rolle, then upwards of eighty, was ascending the steps to the throne, he stumbled and fell. The Queen, forgetting all the ceremonious pomp of the occasion, started forward as if to save him, held out her hand for him to kiss, and expressed a hope that his Lordship was not hurt. Some rather obvious puns were made on the correspondence of the noble Lord’s involuntary action with the title which he bore; and even his daughter was heard to remark, after it had been ascertained that no damage was done, “Oh, it’s nothing! It’s only part of his tenure to play the roll at the Coronation.”

While the Lords were doing homage, the Earl of Surrey, Treasurer of the Household, threw silver medals about the choir and lower galleries, which led to a good deal of rather unseemly scrambling. The choir then sang an anthem, and the Queen received two sceptres from the Dukes of Norfolk and Richmond. Next, divesting herself of her crown, she knelt at the altar, and, after two of the Bishops had read the Gospel and Epistle of the Communion Service, made further offerings to the Church. She then received the Sacrament; the final blessing was given; and the choir sang the anthem, “Hallelujah! for the Lord God Omnipotent reigneth.” Quitting the throne, and passing into the chapel of Edward the Confessor, while the organ played a solemn yet triumphant strain, her Majesty was relieved of her Imperial Robe of State, and arrayed in one of purple velvet. Thus adorned, with the crown upon her head, the sceptre with the cross in the right hand, and the orb in the left, the Queen presented herself at the west door of the Abbey, and, delivering the regalia to gentlemen who attended from the Jewel Office, re-entered the State carriage on her return to the Palace. It was by this time nearly four o’clock, but the streets were still crowded with sight-seers. The peers now wore their coronets, and the Queen her crown; the latter of which (together with the coronets of the Royal Family) blazed with diamonds and other precious stones. State dinners, balls, fireworks, illuminations, feasts to the poor, and a fair in Hyde Park, lasting four days, which was visited by the Queen herself, followed the splendid ceremony of which Westminster Abbey had been the theatre.

In many respects, the proceedings in the Abbey were grand and impressive; but Mr. Greville, the clerk of the Council, lets us a little behind the scenes in the Second Part of his Memoirs. “The different actors in the ceremonial,” he writes, “were very imperfect in their parts, and had neglected to rehearse them. Lord John Thynne, who officiated for the Dean of Westminster, told me that

THE QUEEN RECEIVING THE SACRAMENT AT HER CORONATION.

(After the Painting by C. R. Leslie, R.A.)

nobody knew what was to be done except the Archbishop and himself (who had rehearsed), Lord Willoughby (who is experienced in these matters), and the Duke of Wellington; and consequently there was a continual difficulty and embarrassment, and the Queen never knew what she was to do next. They made her leave her chair, and enter into St. Edward’s Chapel, before the prayers were concluded, much to the discomfiture of the Archbishop. She said to [Lord] John Thynne,

THE DUCHESS OF KENT.

‘Pray tell me what I am to do, for they don’t know;’ and at the end, when the orb was put into her hand, she said to him, ‘What am I to do with it?’ ‘Your Majesty is to carry it, if you please, in your hand.’ ‘Am I?’ she said; ‘it is very heavy.’ The ruby ring was made for her little finger instead of the fourth, on which the rubric prescribes that it should be put. When the Archbishop was to put it on, she extended the former, but he said it must be on the latter. She said it was too small, and she could not get it on. He said it was right to put it there, and, as he insisted, she yielded, but had first to take off her other rings, and then this was forced on; but it hurt her very much, and as soon as the ceremony was over she was obliged to bathe her finger in iced water in order to get it off. The noise and confusion were very great when the medals were thrown about by Lord Surrey, everybody scrambling with all their might and main to get them, and none more vigorously than the Maids of Honour.”

There can be no doubt that on all these occasions mistakes and omissions are numerous. What accidents may have attended the coronation of Queen Elizabeth it is impossible to say, for there were no Memoir-writers in those days; but, in several of his letters, Horace Walpole gives some amusing anecdotes of the unpreparedness of the Court officials at the coronation of George III. In a communication to Sir Horace Mann, dated September 28th, 1761, he says:—“The heralds were so ignorant of their business, that, though pensioned for nothing but to register lords and ladies, and what belongs to them, they advertised in the newspaper for the Christian names and places of abode of the peeresses. The King complained of such omissions, and of the want of precedents: Lord Effingham, the Earl Marshal, told him it was true there had been great neglect in that office, but he had now taken such care of registering directions that next coronation would be conducted with the greatest order imaginable. The King was so diverted with this flattering speech that he made the Earl repeat it several times.”

On the 4th of September, 1838, the King and Queen of the Belgians paid a visit to England. They landed at Ramsgate, and were escorted by Lord Torrington to the Queen at Windsor Castle, where they remained the guests of her Majesty. A fortnight later, a military review took place in Windsor Little Park, when the Queen appeared on horseback in the Windsor uniform, with the badge and ribbon of the Order of the Garter. She had King Leopold, in a Field Marshal’s uniform, on her right, and Lord Hill, Commander of the Forces, on her left, followed by the Duke of Wellington and Lord Palmerston. The King and Queen of the Belgians left the Castle on the 20th, and embarked the following day for Ostend. It was a great delight to the English sovereign to have King Leopold as a visitor, for his advice on affairs of State was highly valuable.

The year 1838 was signalised, among other things, by some events showing the rapid change which science was making in the habits of society. On the 23rd of April, the Great Western steamer arrived at New York, after a voyage of fifteen clear days. This famous ship, and the Sirius, whose voyage was simultaneous almost to a day, were the first vessels which had crossed the Atlantic by steam-power alone, sails having been used in combination with steam on previous occasions. The Great Western was in those days the largest steamer ever known, her tonnage being equal to that of the largest merchant-ships. She was built at Bristol, and sailed from that port on the 7th of April. When she entered the harbour of New York, she had still a surplus of one hundred and forty-eight tons of coal on board, and the problem was solved as to whether a steamer could be constructed large enough to carry sufficient fuel for so long a voyage. The size, tonnage, and speed of this historic vessel have been greatly surpassed in later times; but the fact of a ship crossing the Atlantic in fifteen days was a very genuine astonishment to the people of 1838. Two years later (1840), the Cunard line of steamers was established at Liverpool, which soon entirely eclipsed Bristol as the great commercial port on the western side of England, and as the packet-station for the American service. Another interesting feature of the year 1838 was the opening of the London and Birmingham Railway throughout its entire length. The precise date was the 17th of September, and thenceforward the railway system progressed rapidly. The line in question, however, was not the first that had been placed at the disposal of the public. The original railway for the use of passengers was that constructed by Edward Pease and George Stephenson between Stockton and Darlington, and opened on the 27th of September, 1825. The next was the Liverpool and Manchester Railway, commenced in October, 1826, and opened on the 15th of September, 1830—on which occasion, Mr. Huskisson, a prominent statesman of the time, was accidentally killed. Nevertheless, the development of the system is associated almost entirely with the reign of Queen Victoria, and we hardly think of railways as belonging, even in their inception, to an earlier period.

The Parliamentary Session of 1838 came to a close on the 16th of August. Having taken her seat on the throne, the Queen was addressed by the Speaker of the House of Commons on the subject of the suspension of the constitution of Lower Canada (which had been set aside as a preliminary to the introduction of more liberal arrangements when the rebellion should be suppressed), and on some other matters of less general interest. Her Majesty gave the Royal assent to a number of Bills, and then proceeded to read the Speech, which presents nothing of importance. The Government were heartily glad to be free for some months from the criticism and the menaces of a Parliament not very cordially inclined towards Lord Melbourne and his colleagues. When the House of Commons reassembled after the General Election in 1837, Ministers found themselves with a majority of only twelve. Conservative support saved them from discomfiture on several occasions; but this very fact was not unnaturally considered fatal to their reputation as Whigs. The breach between the Cabinet and the advanced section of the party became wider and more impassable during the session of 1838: the recess, therefore, came as an immense relief. In addition to their troubles in the Lower House, Ministers had to encounter, in the other branch of the Legislature, the invectives of Lord Brougham, who had quarrelled with his old friends in consequence of not being reappointed to the Chancellorship in 1835. The affairs of Canada, moreover, had brought the Whigs into collision with Lord Durham, whose nature was almost as passionate and imperious as that of Brougham himself. Their demerits were probably not so great as their enemies tried to show; but the conduct of affairs was weak, and Tories and Radicals were alike dissatisfied, though often for the most diverse reasons.

A good deal of discontent, also, was growing up in the country itself. The price of bread was high; wages were low; trade was not prosperous; and the operation of the new Poor Law was considered unnecessarily harsh. In the autumn of 1838, meetings were held in various localities, at which some of the speakers addressed inflammatory language to the assembled people, who belonged to the artisan and labouring classes. A body of men had arisen, calling themselves Chartists. They demanded a Charter of popular rights, the six points of

NEWARK CASTLE.

which were Manhood Suffrage, Vote by Ballot, Annual Parliaments, Payment of Members, Abolition of the Property Qualification, and Equal Electoral Districts. Several of these objects have since been carried out, either wholly or nearly so; but, in the days of which we write, they seemed dangerous and visionary in the highest degree. The middle classes, who had carried the Reform Bill of 1832 with the assistance of the grades below them, considered that enough had been done when their own interests were satisfied. A reaction had set in, and the prosperous were afraid of advancing on to the paths of revolution. Even Lord John Russell declared against further organic changes, and, in the absence of any leaders of distinguished social status, the humbler orders took the agitation into their own hands. A sentiment of vague discontent arose very speedily after the passing of the great measure which changed the representation. Bad harvests and general distress gave acrimony to the spirit of political discussion, and in the summer of 1838 a committee of six Members of Parliament and six working men, assembling at Birmingham, prepared a Bill embodying their views of what

MR. DISRAELI IN HIS YOUTH. (After the Portrait by Maclise.)

was required by the country in general, and the labouring classes in particular. This was the document which soon afterwards received the name of “the People’s Charter”—on the suggestion, it is said, of Daniel O’Connell. The direction of the movement fell into the hands of the more violent members. Physical force was threatened; torchlight meetings were held; processions were formed, in which guns, pikes, and other weapons were openly displayed; and on the 12th of December the Government issued a proclamation against all such gatherings. Chartism, however, was not destroyed by this measure. Some degree of truth pervaded its extravagance, and its influence has been felt in later days.

It is about this period, or a little earlier, that we become aware of two great names in modern statesmanship, one of which is still potent in the political world, while the other has but recently passed into the sphere of completed history. Mr. Gladstone—then a young man of twenty-three—was returned for Newark, in December, 1832, to the first reformed Parliament. He was then a Conservative, with the same High Church leanings which, in the midst of considerable changes on other subjects, he has manifested ever since. His ability, his mental culture, and his habits of business, attracted the attention of Sir Robert Peel, who, in his short-lived Administration of 1834-5, made him a Junior Lord of the Treasury, and afterwards Under-Secretary for Colonial Affairs; but it was not until the beginning of Victoria’s reign that he became conspicuous. Probably no one—not even himself—could at that time have anticipated the greatness he was subsequently to achieve; but he was slowly maturing his powers, and acquiring that extraordinary knowledge of public affairs for which he has since been famous.

His rival, Mr. Disraeli, afterwards Lord Beaconsfield, did not enter Parliament until the latter half of 1837—the first Parliament of the reign of Queen Victoria. He was the son of Isaac D’Israeli, an author of distinction, the descendant of a family of Jews, formerly connected with Spain and Italy. Isaac having quarrelled with the Wardens of the Synagogue, his son Benjamin was brought up as a Christian from an early period of his life. By 1837-8, he had made a name for himself by a variety of novels, embodying those political and social ideas which afterwards influenced his conduct as a public man—a sort of Toryism, with an infusion of democratic sympathy. It was as a species of Radical, though with Tory support, that he first endeavoured to obtain a seat in the House of Commons; but a few years later he found no difficulty in displaying the Conservative colours without reserve. The inconsistency, though of course not susceptible of being entirely explained away, was hardly so extreme as might at first appear. Mr. Disraeli hated the Whigs, and objected to several features of the Reform Bill, as giving too much power to the middle classes, and too little to the working classes, and as tending in this way to the increased predominance of the great Whig families. He appeared, therefore, to be attacking the same enemy, whether from a Radical or a Tory platform. In a letter written on the 17th of January, 1874, this was the explanation given by Mr. Disraeli himself. “It seemed to me,” he said, “that the borough constituency of Lord Grey was essentially, and purposely, a Dissenting and low Whig constituency, consisting of the principal employers of labour, and that the ballot was the only instrument to extricate us from these difficulties.” Probably, Mr. Disraeli was consistent from his own point of view, and in his devotion to certain leading ideas; but it is equally obvious that he was resolved to get into Parliament, and that he addressed his appeal at different times to different supporters.

The future Lord Beaconsfield was thirty-three years of age when he entered the House of Commons as the Conservative Member for Maidstone. He was five years older than Mr. Gladstone, and began his Parliamentary career five years later; but, from the close of 1837 to the summer of 1876, when Mr. Disraeli was advanced to the Peerage, both were members of the Lower House, except during the short interval between Mr. Gladstone’s retirement from Newark in 1846 and his election for Oxford University in 1847. The appearance of the representative for Maidstone did not create a favourable impression. He was a dandy, of the type existing in those days, with the addition of a certain Hebrew extravagance and gorgeousness. His long black hair, his sallow countenance, his bottle-green coat and white waistcoat, his profusion of rings and gold chains, his strange gestures and general exaggeration of manner, excited a sense of the ludicrous which was not fortunate for the new-comer. His first attempt at oratory had a disastrous termination. A few years earlier, O’Connell had patronised young Disraeli; but they afterwards quarrelled on political grounds, and, in reply to a savage attack on himself by the Irish agitator, Mr. Disraeli had declared that, as soon as he obtained a seat in the House of Commons, he would inflict on that demagogue such a “castigation” as would make him repent the insults to which he had given utterance. On the 7th of December, 1837, during an Irish debate, he rose to acquit himself of this engagement. The speech had been elaborately prepared, but was too high-flown for the taste of the House. Certain it is that there were frequent interruptions and bursts of laughter; but a good deal of the disturbance appears to have originated with the Irish followers of Mr. O’Connell. The new member struggled bravely for a long time against this ungenerous opposition, but at length gave way, in these memorable words addressed to the Speaker:—“I am not at all surprised, Sir, at the reception I have met with. I have begun several times many things, and I have often succeeded at last. Ay, Sir, and, though I sit down now, the time will come when you will hear me.”

The great figures of Mr. Gladstone and Mr. Disraeli have occupied such prominent positions during the reign of Queen Victoria, that it has seemed necessary to make special reference to their rise as politicians. At this period, both sat on the Conservative side of the House. But their Conservatism was of two very different orders; Mr. Gladstone’s being more of the steady, orthodox kind, while Mr. Disraeli’s shot forth into novelties and unexpected developments, touching on autocracy in one direction, and on democratic power in another. The term “Conservative,” it may be here remarked, arose about the commencement of the Queen’s reign, or at any rate not long before. Since 1832, also, it had been not unusual for certain enthusiasts of the opposite party to call themselves Liberals; but the older members of both bodies preferred the historic appellations of Whig and Tory. “Radical” was another term belonging to the same epoch; so that we find, at the beginning of the Victorian era, all the party watchwords which are still active in the political arena.

The leading events in the earlier months of 1839 were the occupation of Aden, on the 20th of January, by the troops of the East India Company; the opening of Parliament by the Queen in person on the 5th of February; and the arrest by the Chinese Government, on the 7th of April, of Captain Elliot, the superintendent of British trade in China, who was compelled to deliver up opium to the value of £3,000,000. Aden is a town and harbour at the south-western extremity of Arabia. It was at that time a miserable collection of mud huts, containing not more than six hundred inhabitants, but is now, under English rule, a flourishing and populous place of trade, a coaling-station of the Anglo-Indian mails, and a singularly convenient position for communication with Asia and Africa. A British merchant-vessel having been shipwrecked off the coast of Aden, the barbarian natives of which plundered and ill-used the crew, a war-ship was despatched from Bombay in 1838, to oblige the reigning Sultan (a half-savage potentate) to make restitution. It is evident, however, that the East Indian authorities were rather glad of the incident, since it gave them a much-desired pretext for impressing on the petty sovereign of the country—with that persuasiveness which the presence of a ship-of-war so greatly facilitates—the desirability (from our point of view) of ceding Aden and the adjacent lands to the English. The Sultan agreed to the proposal, but afterwards endeavoured to break his promise, when he was compelled by force to submit.

Affairs of this nature have always their questionable side; but the Chinese war was much worse. An English factory was established at Canton in 1680, and several were in existence in 1839. A factory, in the Anglo-Indian sense of the word, is not a place of manufacture, but a place of trade. One of the principal trades we pursued at Canton was the trade in opium, which, having been grown in India, was smuggled into China, in defiance of the express prohibition of the Imperial Government. The use of opium ruined the health, and corrupted the whole moral nature, of innumerable Chinamen; but the culture and exportation of the poisonous drug yielded a large revenue to the Indian Government, as well as a great profit to the traders; and the reasonable wishes of the Chinese authorities were therefore to be disregarded. Frequent dissensions arose in consequence; and at length, in 1839, matters came to a crisis with the arrest of Captain Elliot, and the seizure of the opium over which he had control. A naval war, ultimately supported by a military force, soon afterwards broke out between England and China, and lasted, with brief interruptions, until the 29th of August, 1842, when a treaty of peace was concluded at Nankin, the Imperial sanction of which was received on the 15th of September. Amicable relations were thus re-established for a few years; but at a later period hostilities again broke out, owing to repeated misunderstandings between the British authorities and the Chinese Government. By the Treaty of 1842 (the formal ratifications of which were exchanged between the Emperor and Queen Victoria on the 22nd of July, 1843), it was provided that Amoy, Foochow, Ningpo, and Shanghae, should, in addition to Canton, be thrown open to the British, who were permitted to maintain a consul at each of the five ports; and that the island of Hong-Kong should belong in perpetuity to England. We had succeeded by virtue of superior force; yet such triumphs yield nothing but a feeling of shame to any well-informed

THE COUNCIL CHAMBER, ST. JAMES’S PALACE.

Englishman whose mind is not vitiated by false reasoning or self-interest. The Chinese fought in defence of their cities with a heroism which would have called forth the generous praises of Plutarch; and the pitiable spectacle of brave men slaying their wives and children, and then themselves, rather than fall into the hands of the enemy, should have burnt like red-hot iron into the consciences of the opium-mongers who provoked the war.

These were matters in which the Queen was not immediately concerned, though it would be unfitting to omit them from any account of her reign. But a complication had arisen in Jamaica which led to a Ministerial crisis in England, involving points of constitutional practice that were very important to her Majesty’s position. Slavery had been abolished in Jamaica in the year 1834; but the troubles inseparable from that detestable system did not cease with its abrogation. The planters continued to be insolent and cruel. They evaded the new arrangements in every way they could, and placed themselves in systematic opposition to the Governors sent out from England, whose duty it was to see the laws enforced. The House of Assembly defied the Imperial Government, and ultimately refused to provide for the executive needs of the island until they were allowed to have their own way in all things. On the other hand, it is very probable that the negroes were often indolent, and sometimes presumptuous; though nothing is more surprising than the temper and self-control exhibited by the poor blacks on finding themselves suddenly invested with liberty. The Jamaica embroilment was made all the worse by the imprudence of Lord Sligo, who, while acting as Governor in 1836, committed a gross violation of the privileges of the Assembly. He was compelled by the Home Government to apologise, and soon afterwards gave place to Sir Lionel Smith, who, after a brief period of popularity, became as much at issue with the Assembly as his predecessors. The representative body refused to pass the most necessary laws, and expressed the greatest indignation at a Bill, sanctioned by the Imperial Parliament, for the regulation of prisons in Jamaica, where many cruelties were inflicted on the negroes. Nor was this all; for the unfortunate men of colour were frequently turned out of house and home, together with their families, and left to starve—a fate not absolutely impossible, even in the genial climate of a West India island. The state of things was becoming intolerable, and the Government of Lord Melbourne struck a venturesome blow.

A proposal was brought before Parliament in 1839 to suspend the constitution of Jamaica for five years, and to substitute during that period a provisional government appointed by the Home authorities. However regrettable in itself, the measure seems to have been justified by the circumstances; but the weakness of the Government invited attack on so favourable an opportunity for creating odium. The majority of twelve with which they commenced the new Parliament had by this time fallen even lower, and there was enough to say against their Jamaica policy to give the Opposition an excellent chance of success. The measure was indeed carried by a majority of five at the sitting of May 6th; but this was equivalent to a defeat, and the Ministry at once resigned. The announcement of their resolution was made on the 7th of May, and, on her Majesty sending for the Duke of Wellington on the 8th, she was advised by him to entrust the formation of a new Cabinet to Sir Robert Peel. Accepting this counsel, the Queen commanded the attendance of that statesman at Buckingham Palace, but at the outset encountered him with the discouraging remark that she was much grieved to part with her late Ministers, whose conduct she entirely approved. She added, however, that she felt the step was necessary; that her first object was the good of the country; that she had perfect confidence in Sir Robert, and would give him every assistance in her power in carrying on the Government. Nothing was said on that occasion about the difficulty which afterwards arose, and the composition of the Cabinet proceeded without any material obstruction.

The next day, however, while talking over matters with his intended colleagues, Sir Robert Peel became for the first time aware that the person of the Queen was surrounded by ladies closely related to the Whig statesmen recently in office. This was very naturally considered as involving a special peril to the new Ministry; for, when it was remembered that the Queen had an avowed partiality for the ideas and political conduct of Lord Melbourne, it seemed almost inevitable that ladies so intimately connected with the Melbourne Government would use their position about her Majesty to prejudice and embarrass the incomers. In consequence of these apprehensions, Sir Robert Peel brought the subject before the notice of the sovereign on the same day (May 9th), and stated that, while no change would be required in any of the appointments below the rank of a Lady of the Bedchamber, he should expect that all of the higher class would at once resign. If such should not be the case, he should propose a change, although he thought that in some instances the absence of political feeling might render any alteration unnecessary. On the 10th of May, her Majesty wrote to the Conservative leader:—“The Queen, having considered the proposal made to her yesterday by Sir Robert Peel, to remove the Ladies of her Bedchamber, cannot consent to adopt a course which she conceives to be contrary to usage, and which is repugnant to her feelings.” A few hours later, Sir Robert addressed a communication to the Queen, relinquishing his attempt to form a Government, and recapitulating the circumstances which, in his judgment, rendered that attempt impracticable.

It is difficult to come to any other conclusion than that Sir Robert Peel was right in the view which he took of this matter. He could not have carried on the administration of the country under a perpetual liability to backstairs intrigues. Besides, it was the opinion of very high authorities on constitutional law that the appointments of the Royal Household are State appointments, and therefore dependent on the Ministry of the day. Lord Melbourne and Lord John Russell, however, advised her Majesty to the contrary, and it was the members of the late Government, sitting in council by a questionable stretch of powers that were then merely provisional, who arranged the terms of the letter which the Queen addressed to Sir Robert Peel on the 10th of May. The leader of the Conservatives became for a few days the most unpopular man in England. It was supposed by the Queen, and rather sedulously spread abroad by the Melbourne party, that Peel desired to remove all her personal friends and familiar attendants; but, as we have seen, this was far from being the case. The Whigs endeavoured to create a factitious sentiment on behalf of the Queen by stating that the ladies whose dismissal Peel demanded were “the friends of her Majesty’s youth;” whereas they appear to have been scarcely known to her until their appointment at the beginning of the new reign. That appointment was made on purely political grounds, and the Duchess of Kent was not consulted in the matter. The facts were afterwards made clear by the statesman chiefly concerned; but a great deal of unmerited odium had been incurred, and, in particular, Daniel O’Connell and Feargus O’Connor denounced Sir Robert in unmeasured language, while pouring out fulsome eulogies on the sovereign whose lawful authority they were a few years later to dispute. When the truth became known, a strong reaction set in, and there can be no doubt that what was called the Bedchamber affair was one of the causes of that temporary unpopularity of the Queen to which we have before adverted.

The Melbourne Government resumed office on the 11th of May, and lost no time in adopting a minute in the following terms:—“Her Majesty’s confidential servants, having taken into consideration the letter addressed by her Majesty to Sir Robert Peel on the 10th of May, and the reply of Sir Robert Peel of the same day, are of opinion that, for the purpose of giving to the Administration that character of efficiency and stability, and those marks of the constitutional support of the Crown, which are required to enable it to act usefully to the public service, it is reasonable that the great officers of the Court, and situations in the Household held by Members of Parliament, should be included in the political arrangements made in a change in the Administration; but they are not of opinion that a similar principle should be applied or extended to the offices held by ladies in her Majesty’s Household.” Two years later (at the suggestion of Prince Albert), the question was settled by a compromise which substantially conceded what Sir Robert Peel had required. The restored Whigs introduced another Jamaica Bill, of a less stringent character, which they carried with the assistance, and under the correction, of the Tories; and the session closed in the midst of general distraction, and the errors of a feeble rule.

COBURG. (After a Sketch by Prince Albert.)