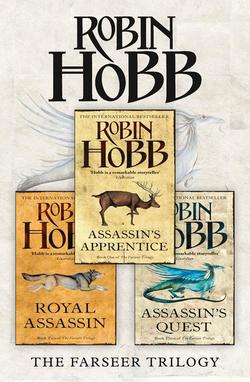

Читать книгу The Complete Farseer Trilogy: Assassin’s Apprentice, Royal Assassin, Assassin’s Quest - Робин Хобб - Страница 19

TEN The Pocked Man

ОглавлениеTime and tide wait for no man. There’s an ageless adage. Sailors and fishermen mean it simply to say that a boat’s schedule is determined by the ocean, not man’s convenience. But sometimes I lie here, after the tea has calmed the worst of the pain, and wonder about it. Tides wait for no man, and that I know is true. But time? Did the times I was born into await my birth to be? Did the events rumble into place like the great wooden gears of the clock of Sayntanns, meshing with my conception and pushing my life along? I make no claim to greatness. And yet, had I not been born, had not my parents fallen before a surge of lust, so much would be different. So much. Better? I think not. And then I blink and try to focus my eyes, and wonder if these thoughts come from me or from the drug in my blood. It would be nice to hold council with Chade, one last time.

The sun had moved round to late afternoon when someone nudged me awake. ‘Your master wants you,’ was all he said, and I roused with a start. Gulls wheeling overhead, fresh sea air and the dignified waddle of the boat recalled me to where I was. I scrambled to my feet, ashamed to have fallen asleep without even wondering if Chade were comfortable. I hurried aft to the ship’s house.

There I found Chade had taken over the tiny galley table. He was poring over a map spread out on it, but a large tureen of fish chowder was what got my attention. He motioned me to it without taking his attention from the map, and I was glad to fall to. There were ship’s biscuits to go with it, and a sour red wine. I had not realized how hungry I was until the food was before me. I was scraping my dish with a bit of biscuit when Chade asked me, ‘Better?’

‘Much,’ I said. ‘How about you?’

‘Better,’ he said, and looked at me with his familiar hawk’s glance. To my relief, he seemed totally recovered. He pushed my dishes to one side and slid the map before me. ‘By evening,’ he said, ‘we’ll be here. It’ll be a nastier landing than the loading was. If we’re lucky, we’ll get wind when we need it. If not, we’ll miss the best of the tide, and the current will be stronger. We may end up swimming the horses to shore while we ride in the dory. I hope not, but be prepared for it, just in case. Once we land …’

‘You smell of carris seed.’ I said it, not believing my own words. But I had caught the unmistakable sweet taint of the seed and oil on his breath. I’d had carris seed cakes, at Springfest, when everyone does, and I knew the giddy energy that even a sprinkling of the seed on a cake’s top could bring. Everyone celebrated Spring’s Edge that way. Once a year, what could it hurt? But I knew, too, that Burrich had warned me never to buy a horse that smelled of carris seed at all. And warned me further that if anyone were ever caught putting carris seed oil on any of our horse’s grain, he’d kill him. With his bare hands.

‘Do I? Fancy that. Now, I suggest that if you have to swim the horses, you put your shirt and cloak into an oilskin bag and give it to me in the dory. That way you’ll have at least that much dry to put on when we reach the beach. From the beach, our road will …’

‘Burrich says that once you’ve given it to an animal, it’s never the same. It does things to horses. He says you can use it to win one race, or run down one stag, but after that, the beast will never be what it was. He says dishonest horse-traders use it to make an animal show well at a sale; it gives them spirit and brightens their eyes, but that soon passes. Burrich says that it takes away all their sense of when they’re tired, so they go on, past the time when they should have dropped from exhaustion. Burrich told me that sometimes when the carris oil wears out, the horse just drops in its tracks.’ The words spilled out of me, cold water over stones.

Chade lifted his gaze from the map. He stared at me mildly. ‘Fancy Burrich knowing all that about carris seed. I’m glad you listened to him so closely. Now perhaps you’ll be so kind as to give me equal attention as we plan the next stage of our journey.’

‘But Chade …’

He transfixed me with his eyes. ‘Burrich is a fine horse-master. Even as a boy he showed great promise. He is seldom wrong … when speaking about horses. Now attend to what I am saying. We’ll need a lantern to get from the beach to the cliffs above. The path is very bad; we may need to bring one horse up at a time. But I am told it can be done. From there, we go overland to Forge. There isn’t a road that will take us there quickly enough to be of any use. It’s hilly country, but not forested. And we’ll be going by night, so the stars will have to be our map. I am hoping to reach Forge by mid-afternoon. We’ll go in as travellers, you and I. That’s all I’ve decided so far; the rest will have to be planned from hour to hour …’

And the moment in which I could have asked him how he could use the seed and not die of it was gone, shouldered aside by his careful plans and precise details. For half an hour more he lectured me on details, and then he sent me from the cabin, saying he had other preparations to make and that I should check on the horses and get what rest I could.

The horses were forward, in a makeshift rope enclosure on deck. Straw cushioned the deck from their hooves and droppings. A sour-faced mate was mending a bit of railing that Sooty had kicked loose in the boarding. He didn’t seem disposed to talk, and the horses were as calm and comfortable as could be expected. I roved the deck briefly. We were on a tidy little craft, an inter-island trader wider than she was deep. Her shallow draught let her go up rivers or right onto beaches without damage, but her passage over deeper water left a lot to be desired. She sidled along, with here a dip and there a curtsey, like a bundle-laden farm-wife making her way through a crowded market. We seemed to be the sole cargo. A deckhand gave me a couple of apples to share with the horses, but little talk. So after I had parcelled out the fruit, I settled myself near them on their straw and took Chade’s advice about resting.

The winds were kind to us, and the captain took us in closer to the looming cliffs than I’d have thought possible, but unloading the horses from the vessel was still an unpleasant task. All of Chade’s lecturing and warnings had not prepared me for the blackness of night on the water. The lanterns on the deck seemed pathetic efforts, confusing me more with the shadows they threw than aiding me with their feeble light. In the end, a deckhand rowed Chade to shore in the ship’s dory. I went overboard with the reluctant horses, for I knew Sooty would fight a lead rope and probably swamp the dory. I clung to Sooty and encouraged her, trusting her common sense to take us toward the dim lantern on shore. I had a long line on Chade’s horse, for I didn’t want his thrashing too close to us in the water. The sea was cold, the night was black, and if I’d had any sense, I’d have wished myself elsewhere; but there is something in a boy that takes the mundanely difficult and unpleasant and turns it into a personal challenge and an adventure.

I came out of the water dripping, chilled and completely exhilarated. I kept Sooty’s reins and coaxed Chade’s horse in. By the time I had them both under control, Chade was beside me, lantern in hand, laughing exultantly. The dory man was already away and pulling for the ship. Chade gave me my dry things, but they did little good pulled on over my dripping clothes. ‘Where’s the path?’ I asked, my voice shaking with my shivering.

Chade gave a derisive snort. ‘Path? I had a quick look while you were pulling in my horse. It’s no path, it’s no more than the course the water takes when it runs off down the cliffs. But it will have to do.’

It was a little better than he had reported, but not much. It was narrow and steep and the gravel on it was loose underfoot. Chade went ahead with the lantern. I followed, with the horses in tandem. At one point Chade’s bay acted up, tugging back, throwing me off-balance and nearly driving Sooty to her knees in her efforts to go the other direction. My heart was in my mouth until we reached the top of the cliffs.

Then the night and the open hillside spread out before us under the sailing moon and the stars scattered wide overhead, and the spirit of the challenge caught me up again. I suppose it could have been Chade’s attitude. The carris seed made his eyes wide and bright, even by lantern light, and his energy, unnatural though it was, was infectious. Even the horses seemed affected, snorting and tossing their heads. Chade and I laughed dementedly as we adjusted harness and then mounted. Chade glanced up to the stars, and then around the hillside that sloped down before us. With careless disdain he tossed our lantern to one side.

‘Away!’ he announced to the night, and kicked the bay, who sprang forward. Sooty was not to be outdone, and so I did as I had never dared before, galloping down unfamiliar terrain by night. It is a wonder we did not all break our necks. But there it is; sometimes luck belongs to children and madmen. That night I felt we were both.

Chade led and I followed. That night, I grasped another piece of the puzzle that Burrich had always been to me. For there is a very strange peace in giving over your judgement to someone else, to saying to them, ‘You lead and I will follow, and I will trust entirely that you will not lead me to death or harm.’ That night, as we pushed the horses hard, and Chade steered us solely by the night sky, I gave no thought to what might befall us if we went astray from our bearing, or if a horse were injured by an unexpected slip. I felt no sense of accountability for my actions. Suddenly, everything was easy and clear. I simply did whatever Chade told me to do, and trusted to him to have it turn out right. My spirit rode high on the crest of that wave of faith, and sometime during the night it occurred to me: this was what Burrich had had from Chivalry, and what he missed so badly.

We rode the entire night. Chade breathed the horses, but not as often as Burrich would have. And he stopped more than once to scan the night sky and then the horizon to be sure our course was true. ‘See that hill there, against the stars? You can’t see it too well, but I know it. By light, it’s shaped like a buttermonger’s cap. Keeffashaw, it’s called. We keep it to the west of us. Let’s go.’

Another time he paused on a hilltop. I pulled in my horse beside his. Chade sat still, very tall and straight. He could have been carved of stone. Then he lifted an arm and pointed. His hand shook slightly. ‘See that ravine down there? We’ve come a bit too far to the east. We’ll have to correct as we go.’

The ravine was invisible to me, a darker slash in the dimness of the starlit landscape. I wondered how he could have known it was there. It was perhaps half an hour later that he gestured off to our left, where on a rise of land a single light twinkled. ‘Someone’s up tonight in Woolcot,’ he observed. ‘Probably the baker, putting early-morning rolls to rise.’ He half-turned in his saddle and I felt more than saw his smile. ‘I was born less than a mile from here. Come, boy, let’s ride. I don’t like to think of Raiders so close to Woolcot.’

And on we went, down a hillside so steep that I felt Sooty’s muscles bunch as she leaned back on her haunches and more than half-slid her way down.

Dawn was greying the sky before I smelled the sea again. And it was still early when we crested a rise and looked down on the little village of Forge. It was a poor place in some ways; the anchorage was good only on certain tides. The rest of the time the ships had to anchor further out and let small craft ply back and forth between them and shore. About all that Forge had to keep it on the map was iron ore. I had not expected to see a bustling city. But neither was I prepared for the rising tendrils of smoke from blackened, open-roofed buildings. Somewhere an unmilked cow was lowing. A few scuttled boats were just off the shore, their masts sticking up like dead trees.

Morning looked down on empty streets. ‘Where are the people?’ I wondered aloud.

‘Dead, taken hostage, or hiding in the woods still.’ There was a tightness in Chade’s voice that drew my eyes to his face. I was amazed at the pain I saw there. He saw me staring at him and shrugged mutely. ‘The feeling that these folk belong to you, that their disaster is your failure … it will come to you as you grow. It goes with the blood.’ He left me to ponder that as he nudged his weary mount into a walk. We threaded our way down the hill and into the town.

Going more slowly seemed to be the only caution Chade was taking. There were two of us, weaponless, on tired horses, riding into a town where …

‘The ship’s gone, boy. A raiding ship doesn’t move without a full complement of rowers. Not in the current off this piece of coast. Which is another wonder. How did they know our tides and currents well enough to raid here? Why raid here at all? To carry off iron ore? Easier by far for them to pirate it off a trading-ship. It doesn’t make sense, boy. No sense at all.’

Dew had settled heavily the night before. There was a rising stench in the town, of burned, wet homes. Here and there a few still smouldered. In front of some, possessions were strewn out into the street, but I did not know if the inhabitants had tried to save some of their goods, or if the Raiders had begun to carry things off and then changed their minds. A salt-box without a lid, several yards of green woollen goods, a shoe, a broken chair: the litter spoke mutely but eloquently of all that was homely and safe broken forever and trampled in the mud. A grim horror settled on me.

‘We’re too late,’ Chade said softly. He reined his horse in and Sooty stopped beside him.

‘What?’ I asked stupidly, jolted from my thoughts.

‘The hostages. They returned them.’

‘Where?’

Chade looked at me incredulously, as if I were insane or very stupid. ‘There. In the ruins of that building.’

It is difficult to explain what happened to me in the next moment of my life. So much occurred, all at once. I lifted my eyes to see a group of people, all ages and sexes, within the burned-out shell of some kind of store. They were muttering among themselves as they scavenged in it. They were bedraggled, but seemed unconcerned by it. As I watched, two women picked up the same kettle at once, a large kettle, and then proceeded to slap at one another, each attempting to drive off the other and claim the loot. They reminded me of a couple of crows fighting over a cheese rind. They squawked and slapped and called one another vile names as they tugged at the opposing handles. The other folk paid them no mind, but went on with their own looting.

This was very strange behaviour for village folk. I had always heard of how after a raid, village folk banded together, cleaning out and making habitable what buildings were left standing, and then helping one another salvage cherished possessions, sharing and making do until cottages could be rebuilt, and store-buildings replaced. But these folk seemed completely careless that they had lost nearly everything and that family and friends had died in the raid. Instead, they had gathered to fight over what little was left.

This realization was horrifying enough to behold.

But I couldn’t feel them either.

I hadn’t seen or heard them until Chade pointed them out. I would have ridden right past them. And the other momentous thing that happened to me at that point was that I realized I was different from everyone else I knew. Imagine a seeing child growing up in a blind village, where no one else even suspects the possibility of such a sense. The child would have no words for colours, or for degrees of light. The others would have no conception of the way in which the child perceived the world. So it was in that moment, as we sat our horses and stared at the folk. For Chade wondered out loud, misery in his voice, ‘What is wrong with them? What’s got into them?’

I knew.

All the threads that run back and forth between folk, that twine from mother to child, from man to woman, all the kinships they extend to family and neighbour, to pets and stock, even to the fish of the sea and bird of the sky – all, all were gone.

All my life, without knowing it, I had depended on those threads of feelings to let me know when other live things were about. Dogs, horses, even chickens had them, as well as humans. And so I would look up at the door before Burrich entered it, or know there was one more new-born puppy in the stall, nearly buried under the straw. So I would wake when Chade opened the staircase. Because I could feel people. And that sense was the one that always alerted me first, that let me know to use my eyes and ears and nose as well, to see what they were about.

But these folk gave off no feelings at all.

Imagine water with no weight or wetness. That is how those folk were to me. Stripped of what made them not only human, but alive. To me, it was as if I watched stones rise up from the earth and quarrel and mutter at one another. A little girl found a pot of jam and stuck her fist in it and pulled out a handful to lick. A grown man turned from the scorched pile of fabric he had been rummaging through and crossed to her. He seized the pot and shoved the child aside, heedless of her angry shouts.

No one moved to interfere.

I leaned forward and seized Chade’s reins as he moved to dismount. I shouted wordlessly at Sooty, and tired as she was, the fear in my voice energized her. She leaped forward, and my jerk on the reins brought Chade’s bay with us. Chade was nearly unseated, but he clung to the saddle, and I took us out of the dead town as fast as we could go. I heard shouts behind us, colder than the howling of wolves, cold as storm wind down a chimney, but we were mounted and I was terrified. I didn’t pull in or let Chade have his own reins back until the houses were well behind us. The road bent, and beside a small copse of trees, I pulled in at last. I don’t think I even heard Chade’s angry demands for an explanation until then.

He didn’t get a very coherent one. I leaned forward on Sooty’s neck and hugged her. I could feel her weariness, and the trembling of my own body. Dimly I felt that she shared my uneasiness. I thought of the empty folk back in Forge and nudged Sooty with my knees. She stepped out wearily and Chade kept pace, demanding to know what was wrong. My mouth was dry and my voice shook. I didn’t look at him as I panted out my fear and a garbled explanation of what I had felt.

When I was silent, our horses continued to pace down the packed earth road. At length I got up my courage and looked at Chade. He was regarding me as if I had sprouted antlers. Once aware of this new sense, I couldn’t ignore it. I sensed his scepticism. But I also felt Chade distance himself from me, just a little pulling-back, a little shielding of self from someone who had suddenly become a bit of a stranger. It hurt all the more because he had not pulled back that way from the folk in Forge. And they were a hundred times stranger than I was.

‘They were like marionettes,’ I told Chade. ‘Like wooden things come to life and acting out some evil play. And if they had seen us, they would not have hesitated to kill us for our horses or our cloaks, or a piece of bread. They …’ I searched for words. ‘They aren’t even animals any more. There’s nothing coming out of them. Nothing. They’re like little separate things. Like a row of books, or rocks or …’

‘Boy,’ Chade said, between gentleness and annoyance, ‘you’ve got to get yourself in hand. It’s been a long night of travel for us, and you’re tired. Too long without a sleep, and the mind starts to play tricks, with waking dreams and …’

‘No.’ I was desperate to convince him. ‘It’s not that. It’s not going without sleep.’

‘We’ll go back there,’ he said reasonably. The morning breeze swirled his dark cloak around him, in a way so ordinary that I felt my heart would break. How could there be folk like those in that village, and a simple morning breeze in the same world? And Chade, speaking in so calm and ordinary a voice? ‘Those folk are just ordinary folk, boy, but they’ve gone through a very bad time, and so they’re acting oddly. I knew a girl who saw her father killed by a bear. She was like that, just staring and grunting, hardly even moving to care for herself, for more than a month. Those folk will recover, when they go back to their ordinary lives.’

‘Someone’s ahead!’ I warned him. I had heard nothing, seen nothing, felt only that tug at the cobweb of sense I’d discovered. But as we looked ahead down the road, we saw that we were approaching the tail-end of a rag-tag procession of people. Some led laden beasts, others pushed or dragged carts of bedraggled possessions. They looked over their shoulders at us on our horses as if we were demons risen from the earth to pursue them.

‘The Pocked Man!’ cried a man close to the end of the line, and he lifted a hand to point at us. His face was drawn with weariness and white with fear. His voice cracked on the words. ‘It’s the legends come to life,’ he warned the others who halted fearfully to stare back at us. ‘Heartless ghosts walk embodied through our village ruins, and the black-cloaked pocked man brings his disease upon us. We have lived too soft, and the old gods punish us. Our fat lives will be the death of us all.’

‘Oh, damn it all. I didn’t mean to be seen like this,’ Chade breathed. I watched his pale hands gather his reins, turning his bay. ‘Follow me, boy.’ He did not look toward the man who still pointed a quavering finger at us. He moved slowly, almost languorously, as he guided his horse off the road and up a tussocky hillside. It was the same unchallenging way of moving that Burrich had when confronting a wary horse or dog. His tired horse left the smooth trail reluctantly. Chade was headed up into a stand of birches on the hilltop. I stared at him uncomprehendingly. ‘Follow me, boy,’ he directed me over his shoulder when I hesitated. ‘Do you want to be stoned in the road? It’s not a pleasant experience.’

I moved carefully, swinging Sooty aside from the road as if I were totally unaware of the panicky folk ahead of us. They hovered there, between anger and fear. The feel of it was a black-red smear on the day’s freshness. I saw a woman stoop, saw a man turn aside from his barrow.

‘They’re coming!’ I warned Chade, even as they raced toward us. Some gripped stones, and others green staffs freshly taken from the forest. All had the bedraggled look of townsfolk forced to live in the open. Here were the rest of Forge’s villagers, those not taken hostage by the Raiders. All of that I realized in the instant between digging in my heels and Sooty’s weary plunge forward. Our horses were spent; their efforts at speed were grudging, despite the hail of rocks that thudded to the earth in our wake. Had the townsfolk been rested, or less fearful, they would have easily caught us. But I think they were relieved to see us flee. Their minds were more fixed on what walked the streets of their village than in fleeing strangers, no matter how ominous.

They stood in the road and shouted and waved their sticks until we were among the trees. Chade had taken the lead and I didn’t question him as he took us on a parallel path that would keep us out of the sight of the folk leaving Forge. The horses had settled back into a grudging plod. I was grateful for the rolling hills and scattered trees that hid us from any pursuit. When I saw a stream glinting, I gestured to it without a word. Silently we watered the horses, and shook out for them some grain from Chade’s supplies. I loosened harness, and wiped their draggled coats with handfuls of grass. For ourselves, there was cold streamwater and coarse travel-bread. I saw to the horses as best as I could. Chade seemed full of his own thoughts, and for a long time I respected their intensity. But finally I could contain my curiosity no longer and I asked the question.

‘Are you really the Pocked Man?’

Chade startled, and then stared at me. There were equal parts amazement and ruefulness in that look. ‘The Pocked Man? The legendary harbinger of disease and disaster? Oh, come, boy, you’re not simple. That legend is hundreds of years old. Surely you can’t believe I’m that ancient.’

I shrugged. I wanted to say, ‘You are scarred, and you bring death’, but I did not utter it. Chade did seem very old to me sometimes, and other times so full of energy that he seemed but a very young man in an old man’s body.

‘No, I am not the Pocked Man,’ he went on, more to himself than to me. ‘But after today, the rumours of him will be spread across the Six Duchies like pollen on the wind. There will be talk of disease and pestilence and divine punishments for imagined wrongdoing. I wish I had not been seen like this. The folk of the kingdom already have enough to fear. But there are sharper worries for us than superstitions. However you knew it, you were right. I have been thinking, most carefully, of everything I saw in Forge. And recalling the words of those villagers who tried to stone us. And the look of them all. I knew the Forge folk, in times past. They were doughty folk, not the type to flee in superstitious panic. But those folk we saw on the road, that was what they were doing. Leaving Forge, forever, or at least so they intend. Taking all that is left that they can carry. Leaving homes their grandfathers were born in. And leaving behind relatives who sift and scavenge in the ruins like witlings.

‘The Raiders’ threat was not an empty one. I think of those folk and I shiver. Something is sorely wrong, boy, and I fear what will come next. For if the Red Ships can capture our folk, and then demand that we pay them to kill them, for fear that they will otherwise return them to us like those ones were – what a bitter choice! And once more they have struck when we were least prepared to deal with it.’ He turned to me as if to say more, then suddenly staggered. He sat down abruptly, his face greying. He bowed his head and covered his face with his hands.

‘Chade!’ I cried out in panic, and sprang to his side, but he turned aside from me.

‘Carris seed,’ he said through muffling hands. ‘The worst part is that it abandons you so suddenly. Burrich was right to warn you about it, boy. But sometimes there are no choices but poor ones. Sometimes, in bad times like these.’

He lifted his head. His eyes were dull, his mouth almost slack. ‘I need to rest now,’ he said as piteously as a sick child. I caught him as he toppled and eased him to the ground. I pillowed his head on my saddlebags, and covered him with our cloaks. He lay still, his pulse slow and his breathing heavy, from that time until afternoon of the next day. I slept that night against his back, hoping to keep him warm, and the next day used what was left of our supplies to feed him.

By that evening he was recovered enough to travel, and we began a dreary journey. We went slowly, going by night. Chade chose our paths, but I led, and often he was little more than a load upon his horse. It took us two days to cover the distance we had traversed in that one wild night. Food was sparse, and talk was even scarcer. Just thinking seemed to weary Chade, and whatever he thought about, he found too bleak for words.

He pointed out where I should kindle the signal fire that brought the boat back to us. They sent a dory ashore for him, and he got into it without a word. That showed how spent he was: he simply assumed I would be able to get our weary horses aboard the ship. So my pride forced me to manage that task, and once aboard, I slept as I had not for days. Then again we offloaded, and made a weary trek back to Neatbay. We came in during the small hours of the morning and Lady Thyme once more took up residence in the inn.

By afternoon of the next day, I was able to tell the innkeeper that she was doing much better and would enjoy a tray from her kitchens if she would send one round to the rooms. Chade did seem better, though he sweated profusely at times, and at such times smelled rancidly sweet of carris seed. He ate ravenously, and drank great quantities of water. But in two days he had me tell the innkeeper that Lady Thyme would be leaving on the morrow.

I recovered more readily, and had several afternoons of wandering Neatbay, gawking at the shops and vendors and keeping my ears wide for the gossip that Chade so treasured. In this way we learned much what we had expected to. Verity’s diplomacy had gone well, and Lady Grace was now the darling of the town. Already I could see an increase in the work on the roads and fortifications. Watch Island’s tower was now manned with Kelvar’s best men, and folk referred to it as Grace Tower now. But they gossiped, too, of how the Red Ships had crept past Verity’s own towers, and of the strange events at Forge. I heard more than once about sightings of the Pocked Man. And the tales they told about the inn fire of those who lived in Forge now gave me nightmares.

Those who had fled Forge told soul-cleaving tales of kinfolk gone cold and heartless. They lived there now, just as if they were still human, but those who had known them best were the least capable of being deceived. Those folk did by day what had never been known to happen at any time in Buckkeep. The evils folk whispered were beyond my imaginings. Ships no longer stopped at Forge. Iron ore would have to be found elsewhere. It was said that no one even wanted to take in the folk that had fled, for who knew what taint they carried. After all, the Pocked Man had shown himself to them. Yet somehow it was harder still to hear ordinary folk say that soon it would be over, that the creatures of Forge would kill one another and thank all that was divine for that. The good folk of Neatbay wished death on those who had once been the good folk of Forge, and wished it as if it were the only good thing left that might befall them. As well it was.

On the night before Lady Thyme and I were to rejoin Verity’s retinue to return to Buckkeep, I awoke to find a single candle burning and Chade sitting up, staring at the wall. Without my saying a word, he turned to me. ‘You must be taught the Skill, boy,’ he said as if it were a decision painfully come by. ‘Evil times have come to us, and they will be with us for a long time. It is a time when good men must create whatever weapons they can. I will go to Shrewd yet again, and this time I will demand it. Hard times are here, boy. And I wonder if they will ever pass.’

In the years to come, I was to wonder that often.