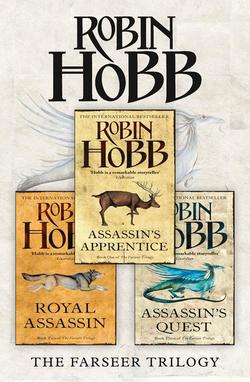

Читать книгу The Complete Farseer Trilogy: Assassin’s Apprentice, Royal Assassin, Assassin’s Quest - Робин Хобб - Страница 22

THIRTEEN Smithy

ОглавлениеThe Lady Patience established her eccentricity at an early age. As a small child, her nursemaids found her stubbornly independent, and yet lacking the common sense to take care of herself. One remarked, ‘She would go all day with her laces undone because she could not tie them herself, yet would suffer no one to tie them for her.’ Before the age of ten, she had decided to eschew the traditional trainings befitting a girl of her rank, and instead interested herself in handicrafts that were very unlikely to prove useful: pottery, tattooing, the making of perfumes, and the growing and propagation of plants, especially foreign ones.

She did not scruple to absent herself for long hours from supervision. She preferred the woodlands and orchards to her mother’s courtyards and gardens. One would have thought this would produce a hardy and practical child. Nothing could be further from the truth. She seemed to be constantly afflicted with rashes, scrapes and stings, was frequently lost, and never developed any sensible wariness toward man or beast.

Her education came largely from herself. She mastered reading and ciphering at an early age, and from that time studied any scroll, book or tablet that came her way with avaricious and indiscriminate interest. Tutors were frustrated by her distractable ways and frequent absences that seemed to affect not at all her ability to learn almost anything swiftly and well. Yet the application of such knowledge interested her not at all. Her head was full of fancies and imaginings, she substituted poetry and music for logic and manners, she expressed no interest at all in social introductions and coquettish skills.

And yet she married a prince, one who had courted her with a single-minded enthusiasm that was to be the first scandal to befall him.

‘Stand up straight!’

I stiffened.

‘Not like that! You look like a turkey, drawn out and waiting for the axe. Relax more. No, put your shoulders back, don’t hunch them. Do you always stand with your feet thrown out so?’

‘Lady, he is only a boy. They are always so, all angles and bones. Let him come in and be at ease.’

‘Oh, very well. Come in, then.’

I nodded my gratitude to a round-faced serving-woman who dimpled a smile at me in return. She gestured me toward a pewbench so bedecked with pillows and shawls that there was scarcely room left to sit. I perched on the edge of it and surveyed Lady Patience’s chamber.

It was worse than Chade’s. I would have thought it the clutter of years if I had not known that she had only recently arrived. Even a complete inventory of the room could not have described it, for it was the juxtaposition of objects that made them remarkable. A feather fan, a fencing glove and a bundle of cattails were all vased in a well-worn boot. A small black terrier with two fat puppies slept in a basket lined with a fur hood and some woollen stockings. A family of carved-ivory walruses perched on a tablet about horse-shoeing. But the dominant elements were the plants. There were fat puffs of greenery overflowing clay pots, teacups and goblets, and buckets of cuttings and cut-flowers, and vines spilling out of handleless mugs and cracked cups. Failures were evident in bare sticks poking up out of pots of earth. The plants perched and huddled together in every location that would catch morning or afternoon sun from the windows. The effect was like a garden spilling in the windows and growing up around the clutter in the room.

‘He’s probably hungry, too, isn’t he, Lacey? I’ve heard that about boys. I think there’s some cheese and biscuits on the stand by my bed. Fetch them for him, would you, dear?’

Lady Patience stood slightly more than arm’s distance away from me as she spoke past me to her lady.

‘I’m not hungry, really, thank you,’ I blurted out before Lacey could lumber to her feet. ‘I’m here because I was told … to make myself available to you, in the mornings, for as long as you wanted me.’

That was a careful rephrasing. What King Shrewd had actually said to me was, ‘Go to her chambers each morning, and do whatever it is she thinks you ought to be doing so that she leaves me alone. And keep doing it until she is as weary of you as I am of her.’ His bluntness had astounded me, for I had never seen him so beleaguered as that day. Verity came in the door of the chamber as I was scuttling out, and he, too, looked much the worse for wear. Both men spoke and moved as if suffering from too much wine the night before, and yet I had seen them both at table last night, and there had been a marked lack of either merriness or wine. Verity tousled my head as I went past him. ‘More like his father every day,’ he remarked to a scowling Regal behind him. Regal glared at me as he entered the King’s chamber and loudly closed the door behind him.

So here I was, in my lady’s chamber, and she was skirting about me and talking past me as if I were an animal that might suddenly strike out at her or soil the carpets. I could tell that it afforded Lacey much amusement.

‘Yes. I already knew that, you see, because I was the one who had asked the King that you be sent here,’ Lady Patience explained carefully to me.

‘Yes, ma’am.’ I shifted on my bit of seat-space and tried to look intelligent and well-mannered. Recalling the earlier times we had met, I could scarcely blame her for treating me like a dolt.

A silence fell. I looked around at things in the room. Lady Patience looked toward a window. Lacey sat and smirked to herself and pretended to be tatting lace.

‘Oh. Here.’ Swift as a diving hawk, Lady Patience stooped down and seized the black terrier pup by the scruff of the neck. He yelped in surprise, and his mother looked up in annoyance as Lady Patience thrust him into my arms. ‘This one’s for you. He’s yours now. Every boy should have a pet.’

I caught the squirming puppy and managed to support his body before she let go of him. ‘Or maybe you’d rather have a bird? I have a cage of finches in my bedchamber. You could have one of them, if you’d rather.’

‘Uh, no. A puppy’s fine. A puppy is wonderful.’ The second half of the statement was made to the pup. My instinctive response to his high-pitched yi-yi-yi had been to quest out to him with calm. His mother had sensed my contact with him, and approved. She settled back into her basket with the white pup with blithe unconcern. The puppy looked up at me and met my eyes directly. This, in my experience, was rather unusual. Most dogs avoided prolonged direct eye-contact. But also unusual was his awareness. I knew from surreptitious experiments in the stable that most puppies his age had little more than fuzzy self-awareness, and were mostly turned to mother and milk and immediate needs. This little fellow had a solidly-established identity within himself, and a deep interest in all that was going on around him. He liked Lacey, who fed him bits of meat, and was wary of Patience, not because she was cruel, but because she stumbled over him and kept putting him back in the basket each time he laboriously clambered out. He thought I smelled very exciting, and the scents of horses and birds and other dogs were like colours in my mind, images of things that as yet had no shape or reality for him, but that he nonetheless found fascinating. I imaged the scents for him and he climbed my chest, wriggling, sniffing and licking me in his excitement. Take me, show me, take me.

‘… even listening?’

I winced, expecting a rap from Burrich, then came back to awareness of where I was and of the small woman standing before me with her hands on her hips.

‘I think something’s wrong with him,’ she observed abruptly to Lacey. ‘Did you see how he was sitting there, staring at the puppy? I thought he was about to go off into some sort of fit.’

Lacey smiled benignly and went on with her tatting. ‘Fair reminded me of you, my lady, when you start pottering about with your leaves and bits of plants and end up staring at the dirt.’

‘Well,’ said Patience, clearly displeased. ‘It is quite one thing for an adult to be pensive,’ she observed firmly. ‘And another for a boy to stand about looking daft.’

Later, I promised the pup. ‘I’m sorry,’ I said, and tried to look repentant. ‘I was just distracted by the puppy.’ He had cuddled into the crook of my arm and was casually chewing the edge of my jerkin. It is difficult to explain what I felt. I needed to pay attention to Lady Patience, but this small being snuggled against me was radiating delight and contentment. It is a heady thing to be suddenly proclaimed the centre of someone’s world, even if that someone is an eight-week-old puppy. It made me realize how profoundly alone I had felt, and for how long. ‘Thank you,’ I said, and even I was surprised at the gratitude in my voice. ‘Thank you very much.’

‘It’s just a puppy,’ Lady Patience said, and to my surprise she looked almost ashamed. She turned aside and stared out the window. The puppy licked his nose and closed his eyes. Warm. Sleep. ‘Tell me about yourself,’ she demanded abruptly.

It took me aback. ‘What would you like to know, lady?’

She made a small, frustrated gesture. ‘What do you do each day? What have you been taught?’

So I attempted to tell her, but I could see that it didn’t satisfy her. She folded her lips tightly at each mention of Burrich’s name. She wasn’t impressed with any of my martial training. Of Chade, I could say nothing. She nodded in grudging approval of my study of languages, writing and ciphering.

‘Well,’ she interrupted suddenly. ‘At least you’re not totally ignorant. If you can read, you can learn anything. If you’ve a will to. Have you a will to learn?’

‘I suppose so.’ It was a lukewarm answer, but I was beginning to feel badgered. Not even the gift of the puppy could outweigh her belittlement of my learning.

‘I suppose you will learn, then. For I have a will that you will, even if you do not yet.’ She was suddenly stern, in a shifting of attitude that left me bewildered. ‘And what do they call you, boy?’

The question again. ‘Boy is fine,’ I muttered. The sleeping puppy in my arms whimpered in agitation. I forced myself to be calm for him.

I had the satisfaction of seeing a stricken look flit briefly across Patience’s face. ‘I shall call you, oh, Thomas. Tom for everyday. Does that suit you?’

‘I suppose so,’ I said deliberately. Burrich gave more thought to naming a dog than that. We had no Blackies or Spots in the stables. Burrich named each beast as if they were royalty, with names that described them or traits he aspired to for them. Even Sooty’s name masked a gentle fire I had come to respect. But this woman named me Tom after no more than an indrawn breath. I looked down so that she couldn’t see my eyes.

‘Fine, then,’ she said, a trifle briskly. ‘Come tomorrow at the same time. I shall have some things ready for you. I warn you, I shall expect willing effort from you. Good day, Tom.’

‘Good day, lady.’

I turned and left. Lacey’s eyes followed me, and then darted back to her mistress. I sensed her disappointment, but did not know what it was about.

It was still early in the day. This first audience had taken less than an hour. I wasn’t expected anywhere; this time was my own. I headed for the kitchens, to wheedle scraps for my pup. It would have been easy to take him down to the stables, but then Burrich would have known about him. I had no illusions about what would happen next. The pup would stay in the stables. He would be nominally mine, but Burrich would see that this new bond was severed. I had no intention of allowing that to happen.

I made my plans. A basket from the launderers, an old shirt over straw for his bed. His messes now would be small, and as he got older, my bond with him would make him easy to train. For now, he’d have to stay by himself for part of each day. But as he got older, he could go about with me. Eventually, Burrich would find out about him. I resolutely pushed that thought aside. I’d deal with that later. For now, he needed a name. I looked him over. He was not the curly-haired yappy type of terrier. He would have a short smooth coat, a thick neck and a mouth like a coal scuttle. But, grown, he’d be less than knee-high, so it couldn’t be too weighty a name. I didn’t want him to be a fighter. So no Ripper or Charger. He would be tenacious, and alert. Grip, maybe. Or Sentry.

‘Or Anvil. Or Forge.’

I looked up. The Fool stepped out of an alcove and followed me down the hall.

‘Why?’ I asked. I no longer questioned the way the Fool could guess what I was thinking.

‘Because your heart will be hammered against him, and your strength will be tempered in his fire.’

‘Sounds a bit dramatic to me,’ I objected. ‘And Forge is a bad word now. I don’t want to mark my pup with it. Just the other day, down in town, I heard a drunk yell at a cut-purse, “May your woman be Forged!” Everyone in the street stopped and stared.’

The Fool shrugged. ‘Well they might.’ He followed me into my room. ‘Smith, then. Or Smithy. Let me see him?’

Reluctantly I gave over my puppy. He stirred, awakened and then wiggled in the Fool’s hands. No smell, no smell. I was astonished to agree with the pup. Even with his little black nose working for me, the Fool had no detectable scent. ‘Careful. Don’t drop him.’

‘I’m a Fool, not a dolt,’ said the Fool, but he sat on my bed and put the pup beside him. Smithy instantly began snuffling and rucking my bed. I sat on the other side of him lest he venture too near the edge.

‘So,’ the Fool asked casually. ‘Are you going to let her buy you with gifts?’

‘Why not?’ I tried to be disdainful.

‘It would be a mistake, for both of you.’ The Fool tweaked Smithy’s tiny tail, and he spun round with a puppy growl. ‘She’s going to want to give you things. You’ll have to take them, for there’s no polite way to refuse. But you’ll have to decide whether they’ll make a bridge between you, or a wall.’

‘Do you know Chade?’ I asked abruptly, for the Fool sounded so like him I suddenly had to know. I had never mentioned Chade to anyone else, save Shrewd, or heard talk of him from anyone around the keep.

‘Shade or sunlight, I know when to keep a grip on my tongue. It would be a good thing for you to learn as well.’ The Fool rose suddenly and went to the door. He lingered there a moment. ‘She only hated you for the first few months. And it wasn’t truly hate of you; it was blind jealousy of your mother, that she could bear a babe to Chivalry, but Patience could not. After that, her heart softened. She wanted to send for you, to raise you as her own. Some might say she merely wanted to possess anything that touched Chivalry. But I don’t think so.’

I was staring at the Fool.

‘You look like a fish, with your mouth open like that,’ he observed. ‘But of course, your father refused. He said it might appear he was formally acknowledging his bastard. But I don’t think that was it at all. I think it would have been dangerous for you.’ The Fool made an odd pass with his hand, and a stick of dried meat appeared in his fingers. I knew it had been up his sleeve, but I was unable to see how he accomplished his tricks. He flipped the meat onto my bed and the puppy sprang on it greedily.

‘You can hurt her, if you choose,’ he offered me. ‘She feels such guilt at how alone you have been. And you look so like Chivalry, anything you say will be as if it came from his lips. She’s like a gem with a flaw. One precise tap from you, and she will fly to pieces. She’s half-mad as she is, you know. They would never have been able to kill Chivalry if she hadn’t consented to his abdication. At least, not with such blithe dismissal of the consequences. She knows that.’

‘Who is “they”?’ I demanded.

‘Who “are” they?’ the Fool corrected me, and whisked out of sight. By the time I got to the door, he was gone. I quested after him, but got nothing. Almost as if he were Forged. I shivered at that thought, and went back to Smithy. He was chewing the meat to slimy bits all over my bed. I watched him. ‘The Fool’s gone,’ I told Smithy. He wagged a casual acknowledgement and went on worrying his meat.

He was mine, given to me. Not a stable-dog I cared for, but mine, and beyond Burrich’s knowledge or authority. Other than my clothes and the copper bracelet that Chade had given me, I had few possessions. But he made up for all lack I might ever have had.

He was a sleek and healthy pup. His coat was smooth now, but would grow bristly as he matured. When I held him up to the window, I could see faint mottlings of colour in his coat. He’d be a dark brindle, then. I discovered one white spot on his chin, and another on his left hind foot. He clamped his little jaws on my shirt-sleeve and shook it violently, uttering savage puppy growls. I tussled him on the bed until he fell into a deep, limp sleep. Then I moved him to his straw cushion and went reluctantly to my afternoon lessons and chores.

That initial week with Patience was a trying time for both of us. I learned to keep a thread of my attention always with Smithy, so he never felt alone enough to howl when I left him. But that took practice, so I felt somewhat distracted. Burrich frowned about it, but I persuaded him it was due to my sessions with Patience. ‘I have no idea what that woman wants from me,’ I told him by the third day. ‘Yesterday it was music. In the space of two hours, she attempted to teach me to play the harp, the sea-pipes, and then the flute. Every time I came close to working out a few notes on one or the other of them, she snatched it away and commanded that I try a different one. She ended that session by saying that I had no aptitude for music. This morning it was poetry. She set herself to teaching me the one about Queen Healsall and her garden. It has a long bit, about all the herbs she grew and what each was for. And she kept getting it bungled, and got angry at me when I repeated it back to her that way, saying that I must know that catmint is not for poultices and that I was mocking her. It was almost a relief when she said I had given her such a headache that we must stop. And when I offered to bring her buds from the ladyshand bush for her headache, she sat right up and said, “There! I knew you were mocking me.” I don’t know how to please her, Burrich.’

‘Why would you want to?’ he growled, and I let the subject drop.

That evening, Lacey came to my room. She tapped, then entered, wrinkling her nose. ‘You’d better bring up some strewing herbs if you’re going to keep that pup in here. And use some vinegar and water when you scrub up his messes. It smells like a stable in here.’

‘I suppose it does,’ I admitted. I looked at her curiously and waited.

‘I brought you this. You seemed to like it best.’ She held out the sea-pipes. I looked at the short, fat tubes bound together with strips of leather. I had liked it best of the three instruments. The harp had far too many strings, and the flute had seemed shrill to me even when Patience had played it.

‘Did Lady Patience send it to me?’ I asked, puzzled.

‘No. She doesn’t know I’ve taken it. She’ll assume it’s lost in her litter, as usual.’

‘Why did you bring it?’

‘For you to practise on. When you’ve a little skill with it, bring it back and show her.’

‘Why?’

Lacey sighed. ‘Because it would make her feel better. And that would make my life much easier. There’s nothing worse than being maid to someone as heartsick as Lady Patience. She longs desperately for you to be good at something. She keeps trying you out, hoping that you’ll manifest some sudden talent, so that she can flout you about and tell folk, “There, I told you he had it in him.” Now I’ve had boys of my own, and I know boys aren’t that way. They don’t learn, or grow, or have manners when you’re looking at them. But turn away, and turn back, and there they are, smarter, taller, and charming everyone but their own mothers.’

I was a little lost. ‘You want me to learn to play this, so that Patience will be happy?’

‘So that she can feel she’s given you something.’

‘She gave me Smithy. Nothing she can ever give me will be better than him.’

Lacey looked surprised at my sudden sincerity. So was I. ‘Well. You might tell her that. But you might also try to learn to play the sea-pipes or recite a ballad or sing one of the old prayers. That she might understand better.’

After Lacey left, I sat thinking, caught between anger and wistfulness. Patience wished me to be a success and felt she must discover something I could do. As if before her, I had never done or accomplished anything. But as I mulled over what I had done, and what she knew of me, I realized that her image of me must be a rather flat one. I could read and write, and take care of a horse or dog. I could also brew poisons, make sleeping-draughts, smuggle, lie and do sleight-of-hand; none of which would have pleased her even if she had known. So, was there anything to me, other than a spy or assassin?

The next morning I arose early and sought Fedwren. He was pleased when I asked to borrow brushes and colours from him. The paper he gave me was better than practice sheets, and he made me promise to show him my efforts. As I made my way up the stairs, I wondered what it would be like to apprentice with him. Surely it could not be any harder than what I had been set to lately.

But the task I had set myself proved harder than any Patience had put me to. I could see Smithy asleep on his cushion. How could the curve of his back be different from the curve of a rune, the shades of his ears so different from the shading of the herbal illustrations I painstakingly copied from Fedwren’s work? But they were, and I wasted sheet after sheet of paper until I suddenly saw that it was the shadows around the pup that made the curve of his back and the line of his haunch. I needed to paint less, not more, and put down what my eye saw rather than what my mind knew.

It was late when I washed out my brushes and set them aside. I had two that pleased, and a third that I liked, though it was soft and muzzy, more like a dream of a puppy than a real puppy. More like what I sensed than what I saw, I thought to myself.

But when I stood outside Lady Patience’s door, I looked down at the papers in my hand and suddenly saw myself as a toddler presenting crushed and wilted dandelions to his mother. What fitting pastime was this for a youth? If I were truly Fedwren’s apprentice, then exercises of this sort would be appropriate, for a good scriber must illustrate and illuminate as well as scribe. But the door opened and there I was, my fingers smudged still with paint and the pages damp in my hand.

I was wordless when Patience irritably told me to come inside, that I was late enough already. I perched on the edge of a chair with a crumpled cloak and some half-finished bit of stitchery. I set my paintings to one side of me, on top of a stack of tablets.

‘I think you could learn to recite verse, if you chose to,’ she remarked with some asperity. ‘And therefore you could learn to compose verse, if you chose to. Rhythm and meter are no more than … is that the puppy?’

‘It’s meant to be,’ I muttered, and could not remember feeling more wretchedly embarrassed in my life.

She lifted the sheets carefully and examined each one in turn, holding them close and then at arm’s length. She stared longest at the muzzy one. ‘Who did these for you?’ she asked at last. ‘Not that it excuses your being late. But I could find good use for someone who can put on paper what the eye sees, with the colours so true. That is the trouble with all the herbals I have; all the herbs are painted the same green, no matter if they are grey or tinged pink as they grow. Such tablets are useless if you are trying to learn from them …’

‘I suspect he’s painted the puppy himself, ma’am,’ Lacey interrupted benignly.

‘And the paper, this is better than what I’ve had to …’ Patience paused suddenly. ‘You, Thomas?’ (And I think that was the first time she remembered to use the name she had bestowed on me.) ‘You paint like this?’

Before her incredulous look, I managed a quick nod. She held up the pictures again. ‘Your father could not draw a curved line, save it was on a map. Did your mother draw?’

‘I have no memories of her, lady.’ My reply was stiff. I could not recall that anyone had ever been brave enough to ask me such a thing before.

‘What, none? But you were five years old. You must remember something: the colour of her hair, her voice, what she called you …’ Was that a pained hunger in her voice, a curiosity she could not quite bear to satisfy?

Almost, for a moment, I did remember. A smell of mint, or was it … it was gone. ‘Nothing, lady. If she had wanted me to remember her, she would have kept me, I suppose.’ I closed my heart. Surely I owed no remembrance to the mother who had not kept me, nor ever sought me since.

‘Well.’ For the first time, I think Patience realized she had taken our conversation into a difficult area. She stared out of the window at a grey day. ‘Someone has taught you well,’ she observed suddenly, too brightly.

‘Fedwren.’ When she said nothing, I added, ‘The court scribe, you know. He would like me to apprentice to him. He is pleased with my letters, and works with me now on the copying of his images. When we have time, that is. I am often busy, and he is often out questing after new paper-reeds.’

‘Paper-reeds?’ she asked distractedly.

‘He has a bit of paper. He had several measures of it, but little by little he has used it. He got it from a trader, who had it from another, and yet another before him, so he does not know where it first came from. But from what he was told, it was made of pounded reeds. The paper is a much better quality than any we make; it is thin, flexible and does not crumble so readily with age; yet it takes ink well, not soaking it up so that the edges of runes blur. Fedwren says that if we could duplicate it, it would change much. With a good, sturdy paper, any man might have a copy of tabletlore from the keep. Were paper cheaper, more children could be taught to write and read, or so he says. I do not understand why he is so …’

‘I did not know any here shared my interest.’ A sudden animation lit the lady’s face. ‘Has he tried paper made from pounded lily-root? I have had some success with that. And also with paper created by first weaving and then wet pressing sheets made with threads of bark from the kinue tree. It is strong and flexible, yet the surface leaves much to be desired. Unlike this paper …’

She glanced again at the sheets in her hand and fell silent. Then she asked hesitantly, ‘You like the puppy this much?’

‘Yes,’ I said simply, and our eyes suddenly met. She stared into me in the same distracted way that she often stared out of the window. Abruptly, her eyes brimmed with tears.

‘Sometimes, you are so like him that …’ She choked. ‘You should have been mine! It isn’t fair, you should have been mine!’

She cried out the words so fiercely that I thought she would strike me. Instead, she leaped at me and caught me in a flying hug, at the same time treading upon her dog and overturning a vase of greenery. The dog sprang up with a yelp, the vase shattered on the floor, sending water and shards in all directions, while my lady’s forehead caught me squarely under the chin, so that for a moment all I saw was sparks. Before I could react, she flung herself from me and fled into her bedchamber with a cry like a scalded cat. She slammed the door behind her.

And all the while Lacey kept on with her tatting.

‘She gets like this, sometimes,’ she observed benignly, and nodded me toward the door. ‘Come again tomorrow,’ she reminded me, and added, ‘You know, Lady Patience has become quite fond of you.’