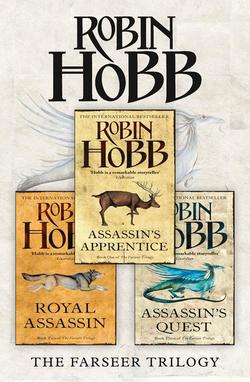

Читать книгу The Complete Farseer Trilogy: Assassin’s Apprentice, Royal Assassin, Assassin’s Quest - Робин Хобб - Страница 25

SIXTEEN Lessons

ОглавлениеAccording to ancient chronicles, Skillusers were organized in coteries of six. These groups did not usually include any of exceptional royal blood, but were limited to cousins and nephews of the direct line of ascension, or those who showed an aptitude and were judged worthy. One of the most famous, Crossfire’s Coterie, provides a splendid example of how they functioned. Dedicated to Queen Vision, Crossfire and the others of her coterie had been trained by a Skillmaster called Tactic. The partners in this coterie were mutually chosen by one another, and then received special training from Tactic to bind them into a close unit. Whether scattered across the Six Duchies to collect or disseminate information, or when massed as a group for the purpose of confounding and demoralizing the enemy, their deeds became legendary. Their final heroism, detailed in the ballad Crossfire’s Sacrifice, was the massing of their strength, which they channelled to Queen Vision during the Battle of Besham. Unbeknownst to the exhausted queen, they gave to her more than they could spare themselves, and in the midst of the victory celebration the coterie was discovered in their tower, drained and dying. Perhaps the people’s love of Crossfire’s Coterie stemmed in part from their all being cripples in one form or another: blind, lame, harelipped or disfigured by fire were all of the six, yet in the Skill their strength was greater than that of the largest warship, and more of a determinant in the defence of the Queen.

During the peaceful years of King Bounty’s reign, the instruction of the Skill for the creation of coteries was abandoned. Existing coteries disbanded due to ageing, death or simply a lack of purpose. Instruction in the Skill began to be limited to princes only, and for a time it was seen as a rather archaic art. By the time of the Red Ship raids, only King Shrewd and his son Verity were active practitioners of the Skill. Shrewd made an effort to locate and recruit former practitioners, but most were aged, or no longer proficient.

Galen, then Skillmaster for Shrewd, was assigned the task of creating new coteries for the defence of the kingdom. Galen chose to set aside tradition. Coterie memberships were assigned rather than mutually chosen. Galen’s methods of teaching were harsh, his training goal that each member would be an unquestioning part of a unit, a tool for the King to use as he needed. This particular aspect was designed solely by Galen, and the first Skill coterie he created, he presented to King Shrewd as if it were his gift to give. At least one member of the royal family expressed his abhorrence of the idea. But times were desperate, and King Shrewd could not resist wielding the weapon that had been given into his hand.

Such hate. Oh, how they hated me. As each student emerged from the stairwell onto the tower roof to find me there and waiting, each spurned me. I felt their disdain, as palpably as if each had dashed cold water against me. By the time the seventh and final student appeared, the cold of their hatred was like a wall around me. But I stood, silent and contained, in my accustomed place, and met every eye that was lifted to mine. That, I think, was why no one spoke a word to me. They were forced to take their places around me. They did not speak to each other, either.

And we waited.

The sun came up, and even cleared the wall around the tower, and still Galen had not come. But they kept their places and waited and so I did likewise.

Finally, I heard his halting steps upon the stairs. When he emerged, he blinked in the sun’s pale wash, glanced at me, and visibly startled. I stood my ground. We looked at one another. He could see the burden of hatred that the others had imposed on me and it pleased him, as did the bandages I still wore on my temple. But I met his eyes and did not flinch. I dared not.

And I became aware of the dismay the others were feeling. No one could look at him and not see how badly he had been beaten. The Witness Stones had found him lacking, and all who saw him would know. His gaunt face was a landscape of purples and greens washed over with yellows. His lower lip was split in the middle, and cut at the corner of his mouth. He wore a long-sleeved robe that covered his arms, but the flowing looseness of it contrasted so strongly with his usual tightly-laced shirts and tunics that it was like seeing the man in his nightshirt. His hands, too, were purple and knobby, but I could not recall that I had seen bruises on Burrich’s body. I concluded that he had used them in a vain attempt to shield his face. He still carried his little whip with him, but I doubted he had the capability to swing it effectively.

And so we inspected one another. I took no satisfaction in his bruises or his disgrace. I felt something akin to shame for them. I had believed so strongly in his invulnerability and superiority that this evidence of his mere humanity left me feeling foolish. That unbalanced his composure. Twice he opened his mouth to speak to me. The third time, he turned his back on the class and said, ‘Begin your physical limbering. I will observe you to see if you are moving correctly.’

The ends of his words were soft, spoken through a painful mouth. And as we dutifully stretched and swayed and bowed in unison, he crabbed awkwardly about the tower garden. He tried not to lean on the wall, or to rest too often. Gone was the slap, slap, slap of the whip against his thigh that had formerly orchestrated our efforts. Instead, he gripped it as if afraid he might drop it. For my part, I was grateful that Burrich had made me get up and move. My bound ribs didn’t permit me the full flexibility of motion that Galen had formerly commanded from us, but I made an honest attempt at it.

He offered us nothing new that day, only going over what we had already learned, and the lessons came to an early end, before the sun was even down. ‘You have done well,’ he offered lamely. ‘You have earned these free hours, for I am pleased you have continued to study in my absence.’ Before dismissing us, he called each of us before him, for a brief touch of the Skill. The others left reluctantly, with many a backward glance, curious as to how he would deal with me. As the numbers of my fellow students dwindled, I braced myself for a solitary confrontation.

But even that was a disappointment. He called me before him, and I came, as silent and outwardly respectful as the others. I stood before him as they had, and he made a few brief passes of his hands before my face and over my head. Then he said in a cold voice, ‘You shield too well. You must learn to relax your guard over your thoughts if you are either to send them forth or receive those of others. Go.’

And I left, as the others had, but regretfully. Privately I wondered if he had made a real attempt to use the Skill on me. I had felt no brush of it. I descended the stairs, aching and bitter, wondering why I was trying.

I went to my room, and then to the stables. I gave Sooty a cursory brushing while Smithy watched. Still I felt restless and dissatisfied. I knew I should rest, that I would regret it if I did not. Stone walk? Smithy suggested, and I agreed to take him into town. He galloped and snuffled circles around me as I made my way down from the keep. It was a blustery afternoon after a calm morning; a storm was building offshore. But the wind was unseasonably warm, and I felt the fresh air clearing my head, and the steady rhythm of walking soothed and stretched the muscles that Galen’s exercises had left bunched and aching. Smithy’s sensory prattle grounded me firmly in the immediate world so that I could not dwell on my frustrations.

I told myself it was Smithy who led us so directly to Molly’s shop. Puppylike, he had returned to where he had been welcomed before. Molly’s father had kept his bed that day, and the shop was fairly quiet. A single customer lingered, talking to Molly. Molly introduced him to me as Jade. He was a mate off some Sealbay trading vessel, not quite twenty, and he spoke to me as if I were ten, smiling past me at Molly all the while. He was full of tales of Red Ships and sea storms. He had a red stone earring in one ear, and a new beard curled along his jaw. He took far too long to select candles and a new brass lamp, but finally he left.

‘Close the store for a bit,’ I urged Molly. ‘Let’s go down to the beach. The wind is lovely today.’

She shook her head regretfully. ‘I’m behind in my work. I should dip tapers all this afternoon if I have no customers. And if I do have customers, I should be here.’

I felt unreasonably disappointed. I quested toward her, and discovered how much she actually wished to go. ‘There’s not that much daylight left,’ I said persuasively. ‘You can always dip tapers this evening. And your customers will come back tomorrow if they find you closed today.’

She cocked her head, looked thoughtful, and abruptly set aside the wicking she held. ‘You’re right, you know. The fresh air will do me good.’ And she took up her cloak with an alacrity that delighted Smithy and surprised me. We closed up the shop and left.

Molly set her usual brisk pace. Smithy frolicked about her, delighted. We talked, in a cursory way. The wind put roses in her cheeks, and her eyes seemed brighter in the cold. And I thought she looked at me more often, and more pensively than she usually did.

The town was quiet, and the market all but deserted. We went to the beach, and walked sedately where we had raced and shrieked but a few years before. She asked me if I had learned to light a lantern before going down steps at night, and that mystified me, until I remembered that I had explained my injuries as a fall down a dark staircase. She asked me if the schoolteacher and the horsemaster were still at odds, and by this I discerned that Burrich and Galen’s challenge at the Witness Stones had become something of a local legend already. I assured her that peace had been restored. We spent some little time gathering a certain kind of seaweed that she wanted to flavour her chowder with that evening. Then, because I was winded, we sat in the lee of some rocks and watched Smithy make numerous attempts to clear the beach of gulls.

‘So. I hear Prince Verity is to wed,’ she began conversationally.

‘What?’ I asked, amazed.

She laughed heartily. ‘Newboy, I have never met anyone as immune to gossip as you seem to be. How can you live right up there in the keep and know nothing of that which is the common talk of the town? Verity has agreed to take a bride, to assure the succession. But the story in town is that he is too busy to do his courting himself, so Regal will find him a lady.’

‘Oh, no.’ My dismay was honest. I was picturing big bluff Verity paired with one of Regal’s sugar-crystal women. Whenever there was a festival of any kind in the keep, Springsedge or Winterheart or Harvestday, here they came, from Chalced and Farrow and Bearns, in carriages or on richly-caparisoned palfreys or riding in litters. They wore gowns like butterflies’ wings, ate as daintily as sparrows, and seemed to flutter about and perch always in Regal’s vicinity. And he would sit in their midst, in his own silk and velvet hues, and preen while their musical voices tinkled around him and their fans and fancywork trembled in their fingers. ‘Prince-catchers’, I’d heard them called, noble women who displayed themselves like goods in a store window in the hopes of wedding one of the royals. Their behaviour was not improper, not quite. But to me it seemed desperate, and Regal cruel as he smiled first on this one and then danced all evening with that one, only to rise to a late breakfast and walk yet another through the gardens. They were Regal’s worshippers. I tried to picture one on Verity’s arm as he stood watching the dancers at a ball, or quietly weaving in his study while Verity pondered and sketched at the maps he so loved. No garden strolls – Verity took his walks along the docks and through the crops, stopping often to talk to the seafolk and farmers behind their ploughs. Dainty slippers and embroidered skirts would surely not follow him there.

Molly slipped a penny into my hand.

‘What’s this for?’

‘To pay for whatever you’ve been thinking so hard that you’ve been sitting on the edge of my skirt while I’ve twice asked you to lift up. I don’t think you’ve heard a word I’ve said.’

I sighed. ‘Verity and Regal are so different, I cannot imagine one choosing a wife for the other.’

Molly looked puzzled.

‘Regal will choose someone who is beautiful and wealthy and of good blood. She’ll be able to dance and sing and play the chimes. She’ll dress beautifully and have jewels in her hair at the breakfast table, and always smell of the flowers that grow in the Rain Wilds.’

‘And Verity will not be glad of such a woman?’ The confusion on Molly’s face was as if I were insisting the sea was soup.

‘Verity deserves a companion, not an ornament to wear on his sleeve,’ I protested in disdain. ‘Were I Verity, I’d want a woman who could do things. Not just select her jewellery or plait her own hair. She should be able to sew a shirt, or tend her own garden, and have something special she can do that is all her own, like scrollwork or herbery.’

‘Newboy, the like of that is not for fine ladies,’ Molly chided me. ‘They are meant to be pretty and ornamental. And they are rich. It isn’t for them to have to do such work.’

‘Of course it is. Look at Lady Patience and her woman, Lacey. They are always about and doing things. Their apartments are a jungle of the lady’s plants, and the cuffs of her gowns are sometimes a bit sticky from her paper-making, or she will have bits of leaves in her hair from her herbery work, but she is still just as beautiful. And prettiness is not all that important in a woman. I’ve watched Lacey’s hands making one of the keep children a fish-net from a bit of jute string. Quick and clever as any webman’s fingers down on the dock are her fingers; now that’s a pretty thing that has nothing to do with her face. And Hod, who teaches weapons? She loves her silver-work and graving. She made a dagger for her father’s birthday, with a grip like a leaping stag, and yet done so cleverly that it’s a comfort in the hand, with not a jag or edge to catch on anything. Now that’s a bit of beauty that will live on long after her hair greys or her cheeks wrinkle. Someday her grandchildren will look at that work and think what a clever woman she was.’

‘Do you think so, really?’

‘Certainly.’ I shifted, suddenly aware of how close Molly was to me. I shifted, yet did not really move further away. Down the beach, Smithy made another foray into a flock of gulls. His tongue was hanging nearly to his knees, but he was still galloping.

‘But if noble ladies do all those things, they’ll ruin their hands with the work, and the wind will dry their hair and tan their faces. Surely Verity doesn’t deserve a woman who looks like a deckhand?’

‘Surely he does. Far more than he deserves a woman who looks like a fat red carp kept in a bowl.’

Molly giggled.

‘Someone to ride beside him of a morning when he takes Hunter out for a gallop, or someone who can look at a section of map he’s just finished and actually understand just how fine a piece of work it is. That’s what Verity deserves.’

‘I’ve never ridden a horse,’ Molly objected suddenly. ‘And I know few letters.’

I looked at her curiously, wondering why she seemed so suddenly downcast. ‘What matter is that? You’re clever enough to learn anything. Look at all you’ve taught yourself about candles and herbs. Don’t tell me that came from your father. Sometimes when I come to the shop, your hair and dress smell of fresh herbs and I can tell you’ve been experimenting to get new perfumes for the candles. If you wanted to read or write more, you could learn. As for riding, you’d be a natural. You’ve balance and strength … look at how you climb the rocks on the cliffs. And animals take to you. You’ve fair won Smithy’s heart away from me …’

‘Fa!’ She gave me a nudge with her shoulder. ‘You talk as if some lord should come riding down from the keep and carry me off.’

I thought of August with his stuffy manners, or Regal simpering at her. ‘Eda forbid. You’d be wasted on them. They wouldn’t have the wit to understand you, or the heart to appreciate you.’

Molly looked down at her work-worn hands. ‘Who would, then?’ she asked softly.

Boys are fools. The conversation had grown and twined around us, my words coming as naturally as breathing to me. I had not intended any flattery, or subtle courtship. The sun was beginning to dip into the water, and we sat close by one another and the beach before us was like the world at our feet. If I had said at that moment, ‘I would,’ I think her heart would have tumbled into my awkward hands like ripe fruit from a tree. I think she might have kissed me, and sealed herself to me of her own free will. But I couldn’t grasp the immensity of what I suddenly knew I had come to feel for her. It drove the simple truth from my lips, and I sat dumb and half a moment later Smithy came, wet and sandy, barrelling into us so that Molly leaped to her feet to save her skirts, and the opportunity was lost forever, blown away like spray on the wind.

We stood and stretched, and Molly exclaimed about the time, and I felt all the sudden aches of my healing body. Sitting and letting myself cool down on a chill beach was a stupid thing I certainly wouldn’t have done to any horse. I walked Molly home and there was an awkward moment at her door before she stooped and hugged Smithy goodbye. And then I was alone, save for a curious pup demanding to know why I went so slowly and insisting he was half-starved and wanting to run and tussle all the way up the hill to the keep.

I plodded up the hill, chilled within and without. I returned Smithy to the stables, and said good night to Sooty, and then went up to the keep. Galen and his fledglings had already finished their meagre meal and left. Most of the keep folk had eaten, and I found myself drifting back to my old haunts. There was always food in the kitchen, and company in the watch-room off the kitchen. Men-at-arms came and went there all hours of the day and night, so Cook kept a simmering kettle on the hook, adding water and meat and vegetables as the level went down. Wine and beer and cheese were also there, and the simple company of those who guarded the keep. They had accepted me as one of their own since the first day I’d been given into Burrich’s care. So I made myself a simple meal, not near as scanty as Galen would have provided me, nor yet as ample and rich as I craved. That was Burrich’s teaching; I fed myself as I would have an injured animal.

And I listened to the casual talk going on around me, focusing myself into the life of the keep as I hadn’t for months. I was amazed at all that I had not known because of my total immersion in Galen’s teaching. A bride for Verity was most of the talk. There was the usual crude soldiers’ jesting one could expect about such things, as well as a lot of commiseration over his ill-luck in having Regal choose his future spouse. That the match would be based on political alliances had never been in question; a prince’s hand could not be wasted on something as foolish as his own choice. That had been a great part of the scandal surrounding Chivalry’s stubborn courtship of Patience. She had come from within the realm, the daughter of one of our nobles, and one already very amicable to the royal family. No political advantage at all had come out of that marriage.

But Verity would not be squandered so. Especially with the Red Ships menacing us all along our straggling coastline. And so speculation ran rife. Who would she be? A woman from the Near Islands, to our north in the White Sea? The islands were little more than rocky bits of the earth’s bones thrusting up out of the sea, but a series of towers set amongst them would give us earlier warning of the sea raiders’ ventures into our waters. To the southwest of our borders, beyond the Rain Wilds where no one ruled were the Spice Coasts. A princess from there would offer few defensive advantages, but some argued for the rich trading agreements she might bring with her. Days to the south and east over the sea were the many big islands where grew the trees that the boat-builders yearned for. Could a king and his daughter be found there who would trade her warm winds and soft fruits for a keep in a rocky, ice-bounded land? What would they ask for a soft southern woman and her tall-timbered island trade? Furs said some, and grain said another. And there were the mountain kingdoms at our backs, with their jealous possession of the passes that led into the tundra lands beyond. A princess from there would command warriors of her folk, as well as trade links to the ivory workers and reindeer herders who lived beyond their borders. On their southern border was the pass that led to the headwaters of the great Rain River that meandered through the Rain Wilds. Every soldier among us had heard the old tales of the abandoned treasure-temples on the banks of that river, of the tall, carved gods who presided still over their holy springs, and of the flake gold that sparkled in the lesser streams. Perhaps a mountain princess, then?

Each possibility was debated with far more political sophistication than Galen would have believed these simple soldiers capable of commanding. I rose from their midst feeling ashamed of how I had dismissed them; in so short a time Galen had brought me to think of them as ignorant sword-wielders, men of brawn with no brain at all. I had lived among them all my life. I should have known better. No, I had known better. But my hunger to set myself higher, to prove beyond doubt my right to that royal magic, had made me willing to accept any nonsense with which he might choose to present me. Something clicked within me, as if the key piece to a wood puzzle had suddenly slid into place. I had been bribed with the offer of knowledge as another man might have been bribed with coins.

I did not think very well of myself as I climbed the stairs to my room. I lay down to sleep with the resolve that I would not let Galen deceive me any longer, nor persuade me to deceive myself. I also resolved most firmly that I would learn the Skill, no matter how painful or difficult it might be.

And so dark and early the next morning, I plunged fully back into my lessons and routine. I attended Galen’s every word, I pushed myself to do each exercise, physical or mental, to the extreme of my ability. But as the week, and then the month, wore painfully on, I felt like a dog with his meat suspended just beyond the reach of his jaws. For the others, something was obviously happening. A network of shared thought was building between them, a communication that had them turning to one another before they spoke, that let them perform the shared physical exercises as one being. Sullenly, resentfully, they took turns being partnered with me, but from them I felt nothing, and from me they shuddered and pulled back, complaining to Galen that the force I exerted towards them was either like a whisper or a battering ram.

I watched in near despair as they danced in pairs, sharing control of one another’s muscles, or as one walked blindfolded the maze of the coals, guided by the eyes of his seated partner. Sometimes I knew I had the Skill. I could feel it building within me, unfolding like a growing seed, but it was a thing I could not seem to direct or control. One moment it was within me, booming like a tide against rock cliffs, and the next it was gone and all within me was dry, deserted sand. At its strength, I could compel August to stand, to bow, to walk. The next he would stand glaring at me, daring me to contact him at all.

And no one seemed able to reach inside me. ‘Drop your guard, put down your walls!’ Galen would angrily order me, as he stood before me, vainly trying to convey to me the simplest direction or suggestion. I felt the barest brush of his Skill against me; but I could no more allow him inside my mind than I could stand complacent while a man slid a sword between my ribs. Try as I might to compel myself, I shied from his touch, physical or mental, and the touches of my classmates I could not feel at all.

Daily they advanced, while I watched and struggled to master the barest basics. A day came when August looked at a page, and across the rooftop his partner read it aloud, while another set of two pairs played a chess game in which those who commanded the moves could not physically see the board at all. Galen was well pleased with all of them, save me. Each day he dismissed us after a touch, a touch I seldom felt. Each day I was the last free to go, and he coldly reminded me that he wasted his time on a bastard only because the King commanded him to do so.

Spring was coming on and Smithy grown from a puppy to a dog. Sooty dropped her foal while I was at my lessons, a fine filly sired by Verity’s stallion. I saw Molly once, and we walked together almost wordlessly through the market. There was a new stall set up, with a rough man selling birds and animals, all captured wild and caged by him. He had crows and sparrows, a swallow, and one young fox so weak with worms he could scarcely stand. Death would free him sooner than any buyer, and even if I had had the coin for him, he had reached a state where the worm-medicines would only poison him as well as his parasites. It sickened me, and so I stood, questing toward the birds with suggestions of how picking at a certain bright bit of metal might unpin the doors of their cages. But Molly thought I stared at the poor beasts themselves, and I felt her grow cooler and further from me than ever she had been before. As we walked her home, Smithy whined beggingly for her attention, and so won from her a cuddle and a pat before we left. I envied him the ability to whine so well. My own seemed to go unheard.

With spring in the air, all in the seaport braced, for soon it would be raiding weather. I ate with the guards every night now, and listened well to all the rumours. Forged ones had become robbers all along our highways, and the stories of their depravities and depredations were all the tavern talk now. As predators, they were more devoid of decency and mercy than any wild animal could be. It was easy to forget they had ever been human, and to hate them with a venom like nothing else.

The fear of being Forged increased proportionately. Markets carried candy-dipped beads of poison for mothers to give their children in the event the family was captured by raiders. There were rumours that some sea-coast villagers had packed up all their belongings in carts and moved inland, forsaking their traditional occupations as fishers and traders to become farmers and hunters away from the threat of the sea. Certainly the population of beggars within the city was swelling. A Forged one came into Buckkeep Town itself and walked the streets, as untouchable as a mad man as he helped himself to whatever he wanted from the market stalls. Before a second day had passed, he had disappeared, and dark whispers said to watch for his body to wash up on the beach. Other rumours said a wife had been found for Verity among the mountain folk. Some said it was to secure our access to the passes; others that we could not afford a potential enemy at our backs when all along our sea-coast we must fear the Red Ships. And there were yet other whispers that all was not well with Prince Verity. Tired and sick said some, and others sniggered about a nervous and weary bridegroom. A few sneered that he had taken to drink and was only seen by day when his headache was worst.

I found my concern over these last rumours to be deeper than I would have expected. None of the royals had ever paid much mind to me, at least not in a personal way. Shrewd saw to my education and comfort, and had long ago bought my loyalty, so that now I was his without even giving thought to any alternative. Regal despised me, and I had long learned to avoid his narrow glance, and the casual nudges or furtive shoves that had once been enough to send a smaller boy staggering. But Verity had been kind to me, in an absent-minded sort of way, and he loved his dogs and his horse and his hawks in a way I understood. I wanted to see him stand tall and proud at his wedding, and hoped someday to stand behind the throne he would occupy much as Chade stood behind Shrewd’s. I hoped he was well, and yet there was nothing I could do about it if he were not, nor any way I could see him. Even if we had been keeping the same hours, the circles we moved in were seldom the same.

It was still not quite full spring when Galen made his announcement. The rest of the keep was making its preparations for Springfest. The stalls in the marketplace would be sanded clean and repainted in bright colours, and tree branches would be brought inside and gently forced so that their blossoms and tiny leaves could grace the banquet table on Springseve. But tender new greens and eggcake with carris seed toppings were not what Galen had in mind for us, nor puppet shows and huntdances. Instead, with the coming of the new season, we would be tested, to be proven either worthy or discarded.

‘Discarded,’ he repeated, and if he had been condemning those unchosen to death, the attention of his other students could not have been more intent. I tried numbly to understand what it would mean to me when I failed. I had no belief that he would test me fairly, or that I could pass such a test even if he did.

‘You shall be a coterie, those of you who prove yourselves. Such a coterie as has never been before, I would think. At the height of Springfest, I myself will present you to your king, and he shall see the wonder of what I have wrought. As you have come this far with me, you know I will not be shamed before him. So I myself will test you, and test you to your limits, to be sure that the weapon I place in my king’s hand holds an edge worthy of its purpose. One day from now, I will scatter you, like seeds in the wind, across the kingdom. I have arranged that you will be taken hence, by swift horse, to your destinations. And there each of you will be left, alone. Not one of you will know where any of the others are.’ He paused, I think to let each of us feel the tension thrumming through the room. I knew that all the others vibrated in tune, sharing a common emotion, almost a common mind, as they received their instruction. I suspected they heard far more than the simple words from Galen’s lips. I felt a foreigner there, listening to words in a language whose idiom I could not grasp. I would fail.

‘Within two days of being left, you will be summoned. By me. You will be directed whom to contact, and where. Each of you will receive the information you need to make your way back here. If you have learned, and learned well, my coterie will be here and present on Springseve, ready to be presented to the King.’ Again the pause. ‘Do not think, however, that all you must do is find your way back to Buckkeep by Springseve. You are to be a coterie, not homing-pigeons. How you come and in what company will prove to me that you have mastered your Skill. Be ready to leave by tomorrow morning.’

And then he released us, one by one, again with a touch for each, and a word of praise for each, save me. I stood before him, as open as I could make myself, as vulnerable as I dared to be, and yet the brush of the Skill against my mind was less than the touch of the wind. He stared down at me as I looked up at him, and I did not need the Skill to feel that he both loathed and despised me. He made a noise of contempt and looked aside, releasing me. I started to go.

‘Far better,’ he said in that cavernous voice of his, ‘if you had gone over the wall that night, bastard. Far better. Burrich thought I abused you. I was only offering you a way out, as close to an honourable way as you were capable of finding. Go away and die, boy, or at least go away. You shame your father’s name by existing. By Eda, I do not know how you came to exist. That a man such as your father could fall to such depth as lying with something and letting you become is beyond my mind to imagine.’

As always, there was that note of fanaticism in his voice as he spoke of Chivalry, and his eyes became almost blank with blind idolatry. Almost absent-mindedly, he turned away and walked off. He reached the top of the stairs, and then turned, very slowly. ‘I must ask,’ he said, and the venom in his voice was hungry with hatred. ‘Are you his catamite, that he lets you suck strength from him? Is that why he is so possessive of you?’

‘Catamite?’ I repeated, not knowing the word.

He smiled. It made his cadaverous face even more skull-like. ‘Did you think I hadn’t discovered him? Did you think you’d be free to draw on his strength for this test? You won’t. Be assured, bastard, you won’t.’

He turned and went down the steps, leaving me standing there alone on the rooftop. I had no idea what his final words meant; but the strength of his hatred had left me sickened and weak as if it were a poison he’d put in my blood. I was reminded of the last time all had left me on the tower roof. I felt compelled to walk to the edge of the tower and look down. This corner of the keep did not face the sea, but there were still jagged rocks aplenty at the foot of it. No one would survive that fall. If I could make a second’s firm decision, then I could put myself out of it all. And what Burrich or Chade or anyone else might think of it would not be able to trouble me.

A distant echo of a whimper.

‘I’m coming, Smithy,’ I muttered, and turned away from the edge.