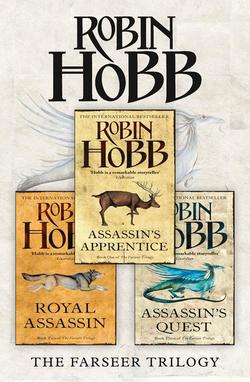

Читать книгу The Complete Farseer Trilogy: Assassin’s Apprentice, Royal Assassin, Assassin’s Quest - Робин Хобб - Страница 28

NINETEEN Journey

ОглавлениеTo speak of the Mountain Kingdom as a kingdom is to start out with a basic misunderstanding of the area and the folk who people it. It is equally inaccurate to refer to the region as Chyurda, although the Chyurda do make up the dominant folk there. Rather than one stretch of united countryside, the Mountain Kingdom consists of various hamlets clinging to the mountainsides, of small vales of arable land, of trading hamlets sprung up along the rough roads that lead to the passes, and clans of nomadic herders and hunters who range the inhospitable countryside in between. Such a diverse people are unlikely to unite, for their interests are often in conflict. Strangely, though, the only force more powerful than each group’s independence and insular ways is the loyalty they bear to the ‘King’ of the mountain folk.

Traditions tell us that this line was begun by a prophet-judge, a woman who was not only wise, but also a philosopher who founded a theory of ruling the keystone which is that the leader is the ultimate servant of the people, and must be totally selfless in that regard. There was no definite time when the judge became the king; rather it was a gradual transition, as word of the fairness and wisdom of the holy one at Jhaampe spread. As more and more folk sought counsel there, willing to be bound by the decision of the judge, it was only natural that the laws of that settlement came to be respected throughout the mountains, and that more and more folk adopted Jhaampe laws as their own. And so judges became kings, but, amazingly, retained their self-imposed decree of servitude and self-sacrifice for their people. The Jhaampe tradition is rife with tales of kings and queens who sacrificed themselves for their folk, in every conceivable way, from fending wild animals off shepherd children to offering themselves as hostages in times of feud.

Tales have been told that make the mountain folk out to be harsh, almost savage. In truth, the land they dwell in is uncompromising, and their laws mirror this condition. It is true that badly-formed infants are exposed, or, more commonly, drowned or drugged to death. The elderly often choose Sequestering, a self-imposed exile in a family but where cold and starvation end all infirmities. A man who breaks his word may have his tongue notched as well as having to surrender double the value of his original bargain. Such customs may seem quaintly barbaric to those in the more settled of the Six Duchies, but they are peculiarly suited to the world of the Mountain Kingdom.

In the end, Verity had his way. There was no sweetness in the triumph for him, I am sure, for his own stubborn insistence was backed by a sudden increase in the frequency of the raids. In the space of a month, two villages were burned and had a total of thirty-two inhabitants taken for Forging. Nineteen of them apparently carried the now popular poison vials, and chose to commit suicide. A third town, a more populous one, was successfully defended, not by the royal troops, but by a mercenary militia the townsfolk had organized and hired themselves. Many of the fighters, ironically, were immigrant Outislanders, using one of the few skills they had. And the mutterings against the King’s apparent inactivity increased.

It did little good to try to explain to them about Verity and the coterie’s work. What the people needed and wanted were warships of their own, defending the coastline. But ships take time to build, and the converted merchant ships that were already in the water were tubby, wallowing things compared to the sleek Red Ships that harassed us. Promises of warships by spring were small comfort to farmers and herders trying to protect this year’s crops and flocks. And the land-locked duchies were becoming more and more vociferous about paying heavier taxes to build warships to protect a coastline they didn’t share. For their part, the leaders of the Coastal Duchies sarcastically wondered how well the inland folk would do without their seaports and trading vessels to outlet their goods. During at least one High Council meeting, there was a noisy altercation in which Duke Ram of Tilth suggested that it would be little loss to cede the Near Islands and Fur Point to the Red Ships if that would slacken their raiding, and Duke Brawndy of Bearns retaliated by threatening to stop all trade traffic along the Bear River and see if Tilth found that as small a loss. King Shrewd managed to bring the council to adjournment before they came to blows, but not before the Farrow Duke had made it clear that he sided with Tilth. The lines of division were being made more sharp with each passing month and each allotment of taxes. Clearly something was needed to rebuild the kingdom’s unity, and Shrewd was convinced it was a royal marriage.

So Regal danced his diplomatic steps, and it was arranged that the Princess Kettricken would make her pledges to Regal in his brother’s stead, with all of her own folk to witness, and Verity’s word would be given by his brother. With a second ceremony to follow, of course, at Buckkeep, with suitable representatives from Kettricken’s folk to witness it. And for the nonce, Regal remained in the Mountain Kingdom’s capital at Jhaampe. His presence there created a regular flow of emissaries, gifts and supplies between Buckkeep and Jhaampe. Seldom did a week pass without a cavalcade either leaving or arriving. It kept Buckkeep in a constant stir.

It seemed to me an awkward and ungainly way to assemble a marriage. Each would be wed almost a month before glimpsing the other. But the political expedients were more important than the feelings of the principals, and the separate celebrations were planned.

I had long since recovered from Verity tapping my strength. It was taking me longer to grasp completely what Galen’s misting of my mind had done to me. I believe I would have confronted him, despite Verity’s counsel, except that he had left Buckkeep, in company of a cavalcade bound for Jhaampe, to ride with them as far as Farrow, where he had relatives he wished to visit. By the time he returned, I myself would be on my way to Jhaampe, so Galen remained out of my reach.

Again, I had too much time on my hands. I still tended Leon, but he did not take more than an hour or two of my time each day. I had been able to discover nothing more about the attack on Burrich, nor did Burrich show any signs of relenting on my ostracism. I had made one jaunt into Buckkeep Town, but when I chanced to wander by the chandlery, it was shuttered and silent. My inquiries at the shop next door brought me the information that the chandlery had been closed for ten days or more, and that unless I wished to buy some leather harness, I could go elsewhere and stop bothering him. I thought of the young man I had last seen with Molly, and bitterly wished them no good of each other.

For no other reason than that I was lonely, I decided to seek out the Fool. Never before had I tried to initiate a meeting with him. He proved more elusive than I had ever imagined.

After a few hours of randomly wandering the keep, hoping to encounter him, I made brave enough to go to his chamber. I had known for years where it was, but had never gone there before, and not simply because it was in an out of the way part of the keep. The Fool did not invite intimacy, except of the kind he chose to offer, and only when he chose to offer it. His chambers were a tower-top room. Fedwren had told me that it had once been a map room, and had offered an unobstructed view of the land surrounding Buckkeep, but later additions to Buckkeep had blocked the views, and higher towers supplanted it. It had outlived its usefulness for anything, save chambers for a Fool.

I climbed to it, that one day toward the beginning of harvest-time. It was already a hot and sticky day. The tower was a closed one, save for arrow slits that did little more than illuminate the dust motes my feet set to dancing in the still air. At first the darkness of the tower had seemed cooler than the stuffy day outside, but as I climbed, it seemed to get hotter and more close, so that by the time I reached the last landing, I felt as if there were no air left to breathe at all. I lifted a weary fist and pounded on the stout door. ‘It’s me, Fitz!’ I called, but the still, hot air muffled my voice like a wet blanket smothering a flame.

Shall I use that as an excuse? Shall I say I thought perhaps he could not hear me, and so I went in to see if he was there? Or shall I say that I was so hot and thirsty that I entered to see if his chambers offered any hint of air or water? Why doesn’t matter, I suppose. I put my hand to the door-latch, and it lifted and I went inside.

‘Fool?’ I called, but I could feel he wasn’t there. Not as I usually felt folk’s presence or absence, but by the stillness that met me. Yet I stood in the door and gawked at a soul laid bare.

Here was light, and flowers, and colours in profusion. There was a loom in the corner, and baskets of fine, thin thread in bright, bright hues. The woven coverlet on the bed, and the drapings on the open windows were unlike anything I had ever seen, woven in geometric patterns that somehow suggested fields of flowers beneath a blue sky. A wide pottery bowl held floating flowers and a slim silver fingerling swam about the stems and above the bright pebbles that floored it. I tried to imagine the pale cynical Fool in the midst of all this colour and art. I took a step further into the room, and saw something that moved my heart aside in my chest.

A baby. That was what I took it for at first, and without thinking, I took the next two steps and knelt beside the basket that cradled it. But it was not a living child, but a doll, crafted with such incredible art that almost I expected to see the small chest move with breath. I reached a hand to the pale, delicate face, but dared not touch it. The curve of the brow, the closed eyelids, the faint rose that suffused the tiny cheeks, even the small hand that rested on top of the coverlets were more perfect than I supposed a made thing could be. Of what delicate clay it had been crafted, I could not guess, nor what hand had inked the tiny eyelashes that curled on the infant’s cheek. The tiny coverlet was embroidered all over with pansies, and the pillow was of satin. I don’t know how long I knelt there, as silent as if it were truly a sleeping babe. But eventually I rose, and backed out of the Fool’s room, and then drew the door silently closed behind me. I went slowly down the myriad steps, torn between dread that I might encounter the Fool coming up, and burdened with the knowledge that I had discovered one denizen of the keep who was at least as alone as I was.

Chade summoned me that night, but when I went to him, he seemed to have no more purpose in calling me than to see me. We sat almost silently before the black hearth, and I thought he looked older than he ever had. As Verity was devoured so Chade was consumed. His bony hands appeared almost desiccated, and the whites of his eyes were webbed with red. He needed to sleep, but instead had chosen to call me. Yet he sat, still and silent, scarce nibbling at the food he had placed before us. At length, I decided to help him.

‘Are you afraid I won’t be able to do it?’ I asked him softly.

‘Do what?’ he asked absently.

‘Kill the mountain prince. Rurisk.’

Chade turned to look at me full-face. The silence held for a long moment.

‘You didn’t know King Shrewd had given me this,’ I faltered.

Slowly he turned back to the empty hearth, and studied it as carefully as if there were flames to read. ‘I’m only the tool-maker,’ he said at last, quietly. ‘Another man uses what I make.’

‘Do you think this is a bad … task? Wrong?’ I took a breath. ‘From what I’ve been told, he has not that much longer to live anyway. It might almost be a mercy, if death were to come quietly in the night, instead of …’

‘Boy,’ Chade remarked quietly. ‘Never pretend we are anything but what we are. Assassins. Not merciful agents of a wise king. Political assassins dealing death for the furtherance of our monarchy. That is what we are.’

It was my turn to study the ghosts of the flames. ‘You are making this very hard for me. Harder than it already was. Why? Why did you make me what I am, if you then try to weaken my resolve …’ My question died away, half-formed.

‘I think … never mind. Maybe it is a kind of jealousy in me, my boy. I wonder, I suppose, why Shrewd uses you instead of me. Maybe I fear I have outlived my usefulness to him. Maybe, now that I know you, I wish I had never set out to make you what …’ And it was Chade’s turn to fall silent, his thoughts going where his words could not follow them.

We sat contemplating my assignment. This was not the serving of a king’s justice. This was not a death sentence for a crime. This was a simple removal of a man who was an obstacle to greater power. I sat still until I began to wonder if I would do it. Then I lifted my eyes to a silver fruit-knife driven deep into Chade’s mantelpiece, and I thought I knew the answer.

‘Verity had made complaint, on your behalf,’ Chade said suddenly.

‘Complaint?’ I asked weakly.

‘To Shrewd. First, that Galen had mistreated you and cheated you. This complaint he made formally, saying that he had deprived the kingdom of your Skill, at a time when it would have been most useful. He suggested to Shrewd, informally, that he settle it with Galen, before you took matters into your own hands.’

Looking at Chade’s face, I could see that the full content of my discussion with Verity had been revealed to him. I was not sure how I felt about that. ‘I would not do that, take my own revenge on Galen. Not after Verity asked me not to.’

Chade gave me a look of quiet approval. ‘So I told Shrewd. But he said to me that I must say to you, that he will settle this. This time the King works his own justice. You must wait and be satisfied.’

‘What will he do?’

‘That I do not know. I do not think Shrewd himself knows yet. The man must be rebuked. But we must keep in time that if other coteries are to be trained, Galen must not feel too badly treated.’ Chade cleared his throat, and said more quietly, ‘And Verity made another complaint to the King as well. He accused Shrewd and I, quite bluntly, of being willing to sacrifice you for the sake of the kingdom.’

This, I knew suddenly, was why Chade had called me tonight. I was silent.

Chade spoke more slowly. ‘Shrewd claimed he had not even considered it. For my part, I had no idea such a thing was possible.’ He sighed again, as if parting with these words cost him. ‘Shrewd is a king, my boy. His first concern must always be for his kingdom.’

The silence between us stretched long. ‘You are saying he would sacrifice me. Without a qualm.’

He did not take his eyes from the fireplace. ‘You. Me. Even Verity, if he thought it necessary for the survival of the kingdom.’ Then he did turn to look at me. ‘Never forget that,’ he said.

The night before the wedding caravan was to leave Buckkeep, Lacey came tapping on my door. It was late, and when she said Patience wished to see me, I foolishly asked, ‘Now?’

‘Well, you leave tomorrow,’ Lacey pointed out, and I obediently followed her as if that made sense.

I found Patience sitting up in a cushioned chair, an extravagantly-embroidered robe on over her nightclothes. Her hair was down about her shoulders, and as I seated myself where she indicated, Lacey resumed the brushing of it.

‘I have been waiting for you to come to apologize to me,’ Patience observed.

I immediately opened my mouth to do so, but she irritably waved me to silence.

‘But, in discussing it with Lacey tonight, I found I had already forgiven you. Boys, I decided, simply have a given amount of rudeness they must express. I decided you meant nothing by it, hence you do not need to apologize.’

‘But I am sorry,’ I protested. ‘I just couldn’t decide how to say …’

‘It’s too late to apologize now, I’ve forgiven you,’ she said briskly. ‘Besides, there isn’t time. I’m sure you should be asleep by now. But as this is your first real venture into court life, I wanted to give you something before you left.’

I opened my mouth, then shut it again. If she wanted to consider this my first real venture into court life, I wouldn’t argue with her.

‘Sit here,’ she said imperiously, and pointed to a spot by her feet.

I went and sat obediently. For the first time, I noticed a small box in her lap. It was of dark wood, and a stag was carved into the lid in bas relief. As she opened it, I caught a whiff of the aromatic wood. She took out an ear stud and held it up to my ear. ‘Too small,’ she muttered. ‘What is the sense of wearing jewellery if no one else can see it?’ She held up and discarded several others, with similar comments. Finally she held up one that was like a silver bit of net with a blue stone caught in it. She made a face over it, then nodded reluctantly. ‘That man has taste. Whatever else he lacks, he has taste.’ She held it up to my ear again, and with absolutely no warning, thrust the pin of it through my earlobe.

I yelped and clapped a hand over my ear, but she slapped it away. ‘Don’t be such a baby. It only stings for a minute.’ There was a sort of clasp that held it behind, and she ruthlessly bent my ear in her fingers to fasten it. ‘There. That quite suits him, don’t you think, Lacey?’

‘Quite,’ Lacey agreed over her eternal tatting.

Patience dismissed me with a gesture. As I rose to go, she said, ‘Remember this, Fitz. Whether you can Skill or not, whether you wear his name or not, you are Chivalry’s son. See that you behave with honour. Now go and get some sleep.’

‘With this ear?’ I asked, showing her blood on my fingertips.

‘I hadn’t thought. I’m sorry …’ she began, but I interrupted her.

‘Too late to apologize. I’ve already forgiven you. And thank you.’ Lacey was still giggling as I left.

I arose early the next morning, to take my place in the wedding cavalcade. Rich gifts must be taken as a token of the new bond between the families. There were gifts for the Princess Kettricken herself, a fine-blooded mare, jewellery, fabric for garments, servants, and rare perfumes. And there were the gifts to her family and people. Horses and hawks and worked gold for her father and brother of course, but the more important gifts were the ones offered to her kingdom, for in keeping with the Jhaampe traditions, she was of her people more than she was of her family. And so there was breeding stock, cattle, sheep, horses and fowl, and powerful yew bows such as the mountain folk did not have, and metalworking tools of good Forge iron, and other gifts judged likely to improve the lot of the mountain people. And there was knowledge, in the form of several of Fedwren’s best illustrated herbals, several tablets of cures, and a scroll on hawking that was a careful copy of one created by Hawker himself. These last, ostensibly, were my purpose in accompanying the caravan.

They were given into my keeping, along with a generous supply of the herbs and roots mentioned in the herbal, and with seed for growing those that did not keep well. This was not a trivial gift, and I took my responsibility for seeing it well delivered as seriously as I took my other mission. All was carefully wrapped and then placed in a carved cedar chest. I was checking their wrappings a final time before taking the chest down to the courtyard when I heard the Fool behind me.

‘I brought you this.’

I turned to find him standing just inside the door of my room. I hadn’t even heard the door open. He was proffering a leather drawstring bag. ‘What is it?’ I asked, and tried not to let him hear either the flowers or the doll in my voice.

‘Seapurge.’

I raised my eyebrows. ‘A cathartic? As a marriage gift? I suppose some would find it appropriate, but the herbs I am taking can be planted and grown in the mountains. I do not think …’

‘It is not a wedding gift. It is for you.’

I accepted the pouch with mixed feelings. It was an exceptionally powerful purge. ‘Thank you for thinking of me. But I am not usually prone to travellers’ ailments, and …’

‘You are not usually, when you travel, in danger of being poisoned.’

‘Is there something you’d like to tell me?’ I tried to make my tone light and bantering. I missed the Fool’s usual wry faces and mockeries from this conversation.

‘Only that you’d be wise to eat lightly, or not at all, of any food you do not prepare yourself.’

‘At all the feasts and festivities that will be there?’

‘No. Only at the ones you wish to survive.’ He turned to go.

‘I’m sorry,’ I said hastily. ‘I didn’t mean to intrude. I was looking for you, and I was so hot, and the door wasn’t latched, so I went in. I didn’t mean to pry.’

His back was to me and he didn’t turn back as he asked, ‘And did you find it amusing?’

‘I –’ I could not think of anything to say, of any way to assure him that what I had seen there would stay only within my own mind. He took two steps and was closing the door. I blurted, ‘It made me wish there were a place as much me as that place is you. A place I would keep as secret.’

The door halted a handsbreadth short of closed. ‘Take some advice, and you may survive this trip. When considering a man’s motives, remember you must not measure his wheat with your bushel. He may not be using the same standard at all.’

And the door closed and the Fool was gone. But his last words had been cryptic and frustrating enough that I thought perhaps he had forgiven me my trespass.

I stuffed the seapurge into my jerkin, not wanting it, but afraid to leave it now. I glanced about my room, but as always it was a bare and practical place. Mistress Hasty had seen to my packing, not trusting me with my new garments. I had noticed that the barred buck on my crest had been replaced with a buck with his antlers lowered to charge. ‘Verity ordered it,’ was all she said when I asked about it. ‘I like it better than the barred buck myself. Don’t you?’

‘I suppose so,’ I replied, and that had been the end of it. A name and a crest. I nodded to myself, shouldered my chest of herbs and scrolls, and went down to join the caravan.

As I was going down the steps, I encountered Verity coming up. At first I scarcely knew him, for he was ascending like a crabbed old man. I stepped out of his way to let him pass, and then knew him as he glanced at me. It is a strange thing to see a once-familiar man like that, encountered as a stranger. I marked how his clothes hung on him now, and the bushy dark hair I remembered had a peppering of grey. He smiled absently at me, and then, as if it had suddenly occurred to him, he stopped me.

‘You’re leaving for the Mountain Kingdom? For the wedding ceremony?’

‘Yes.’

‘Do me a favour, boy?’

‘Of course,’ I said, taken aback by the rust in his voice.

‘Speak well of me to her. Truthfully, mind you, I’m not asking for lies. But speak well of me. I’ve always thought that you thought well of me.’

‘I do,’ I said to his retreating back. ‘I do, sir.’ But he didn’t turn or make a reply, and I felt much as I had when the Fool left me.

The courtyard was a milling of folk and animals. There were no carts this time; the roads into the mountains were notoriously bad, and it had been decided that pack animals would have to suffice for the sake of swiftness. It would not do for the royal entourage to be late for the wedding; it was bad enough that the groom was not attending.

The flocks and herds had been sent on days before. It was expected that our trip would take two weeks, and three had been allowed for it. I saw to fastening the cedar chest onto a pack animal, and then stood beside Sooty and waited. Even in the cobbled courtyard, dust stirred thick in the hot summer air. Despite all the careful planning that had gone into it, the caravan seemed chaotic. I glimpsed Sevrens, Regal’s favourite valet. Regal had sent him back to Buckkeep a month ago, with specific instructions about certain garments he wished created. Sevrens was following Hands, dithering and expostulating about something, and whatever it was, Hands was not looking patient about it. When Mistress Hasty had been giving me final instructions on the care of my new garments, she had divulged that Sevrens was taking enough new garments, hats and accoutrements for Regal that he had been allotted three pack animals to carry them. I imagined that caring for the three animals had fallen to Hands, for Sevrens was an excellent valet, but timid around the larger animals. Rowd, Regal’s ready man, hulked after both of them, looking ill-tempered and impatient. On one wide shoulder he carried yet another trunk, and perhaps the loading of this additional item was what was fretting Sevrens. I soon lost sight of them in the crowd.

I was surprised to discover Burrich checking the lead-lines on the breeding horses and the Princess’s gift mare. Surely whoever was in charge of them could do that, I thought. And then, as I saw him mount, I realized that he, too, would be part of this procession. I looked about to see who was accompanying him, but saw none of the stable-boys I knew, save Hands … Cob was already in Jhaampe with Regal. So Burrich had taken this on himself. I was not surprised.

August was there, astride a fine grey mare, waiting with an impassivity that was almost inhuman. Already his time in the coterie had changed him. Once he had been a chubby youth, quiet but pleasant. He had the same black bushy hair as Verity, and I had heard it said that he resembled his cousin as a boy. I reflected that as his Skill duties increased, he would probably resemble Verity even more. He would be present at the wedding, as a sort of window for Verity as Regal uttered the vows on his brother’s behalf. Regal’s voice, August’s eyes, I mused to myself. What did I go as? His poignard?

I mounted Sooty, as much to be up and away from the folk exchanging goodbyes and last-minute instructions as for any other reason. I wished to Eda we could be away and on the road. It seemed to take forever for the straggling line to form and for the tying and strapping of bundles to be accomplished. And then, almost abruptly, the standards were lifted, a horn was blown, and the line of horses, laden pack-animals and folk began to move. I looked up once, to see that Verity had actually come out to stand on top of the tower and watch us depart. I waved up at him, but doubted that he knew me amidst so many. And then we were out of the gates, and winding up the hilly path that led away from Buckkeep and to the west.

Our path would lead us up the banks of the Buck River, which we would ford at its wide shallows near where the borders of Buck and Farrow Duchies touched. From there we would journey across Farrow’s wide plains, in baking heat I had never encountered before, until we reached Blue Lake. From Blue Lake, we would follow a river named simply Cold whose origins were in the Mountain Kingdom. From the Cold Ford the trading road began, that led between the mountains and through their shadows and up, ever up, to Storm Pass, and thence to the thick green forests of the Rain Wilds. We would not go as far as that, but would stop at Jhaampe, which was as close to a city as the Mountain Kingdom possessed.

In some ways, it was an unremarkable journey, if one discounts all that inevitably goes with such journeys. After the first three days or so, things settled into a remarkably monotonous routine, varied only by the different countryside we passed. Every little village or hamlet along our road turned out to greet us and delay us, with official best wishes and felicitations for the Crown Prince’s wedding festivities.

But after we reached the wide plains of Farrow, such hamlets were few and far between. Farrow’s rich farms and trading cities were far to the north of our path, along the Vin River. We travelled Farrow’s plains, where people were mostly nomadic herders, creating towns only in the winter months when they settled along the trade routes for what they called ‘the green season’. We passed herds of sheep, goats, or horses; or more rarely, the dangerous, rangy swine they called haragars, but our contact with the people of that region was usually limited to the sight of their conical tents in the distance, or some herder standing tall in his saddle, holding aloft his crook in greeting.

Hands and I became reacquainted. We would share food and a small cook-fire in the evenings, and he would regale me with tales of Sevren’s nattering worries of dust getting into silk robes or bugs getting into fur collars and velvet getting chafed to pieces during the long trek. Grimmer were his complaints about Rowd. I myself had no fond memories of the man, and Hands found him an oppressive travelling companion, for he seemed to constantly suspect Hands of trying to steal from the packs of Regal’s belongings. One evening Rowd even found his way to our fire, where he laboriously delivered a vague and indirect warning against any who might conspire to steal from his master.

The fair weather held, and if we sweated by day, it was pleasant enough by night. I slept on top of my blanket, and seldom bothered with any other shelter. Each night I checked the contents of my trunk, and did my best to keep the roots from becoming completely desiccated, and to keep the shifting from putting wear on the scrolls and tablets. One night I awoke to a loud whinnying from Sooty, and thought that the cedar chest had been moved slightly from where I placed it. But a brief check of its contents proved that all was in order, and when I mentioned it to Hands, he merely asked if I were catching Rowd’s disease.

The hamlets and herds we passed frequently provided us with fresh foods, and were most generous in their allocation of it, so we had little hardship on the journey. Open water was not as plentiful as we could have wished as we crossed Farrow, but each day we found some spring or dusty well to water at, so even that was not as bad as it might have been.

I saw very little of Burrich. He arose earlier than the rest of us, and preceded the main caravan, that his charges might have the best grazing and the cleanest water. I knew he would want his horses in prime condition when they arrived at Jhaampe. August, too, was almost invisible. While he was technically in charge of our expedition, he left the running of it to the captain of his honour-guard. I could not decide if he did this out of wisdom, or laziness. In any event, he kept mostly to himself, although he did allow Sevrens to tend him and share his tent and meals.

For me, it was almost a return to a sort of childhood. My responsibilities were very limited. Hands was a genial companion, and it took very little encouragement to have him telling from his vast store of tales and gossip. I often went for almost the whole day before I would recall that, at the end of this journey, I would kill a prince.

Such thoughts usually came on me when I awoke in the dark part of the night. Farrow’s sky seemed to be much thicker with stars than the night over Buckkeep, and I would stare up at them, and mentally rehearse ways to put an end to Rurisk. There was another chest, a tiny one, packed carefully within the bag that held my clothing and personal items. I had compiled it with much thought and anxiety for this assignment must be carried out perfectly. It must be done cleanly, with not even the tiniest suspicion raised. And timing was critical. The prince must not die while we were at Jhaampe. Nothing must cast the slightest shadow upon the nuptials. Nor must he die before the ceremonies were observed at Buckkeep and the wedding safely consummated, for that might be seen as an ill omen for the couple. It would not be an easy death to arrange.

Sometimes I wondered why it had been entrusted to me instead of to Chade. Was it a test of some sort, one that if I failed I would be put to death? Was Chade too old for this challenge, or too valuable to be risked for this? Could he simply not be spared from tending Verity’s health? And when I reined my mind away from these questions, I was left wondering whether to use a powder that would irritate Rurisk’s damaged lungs so he might cough himself to death. Perhaps I might treat his pillows and bedding with it. Should I offer him a pain remedy, one that would slowly addict him and lure him into a sleeping death? I had a blood-thinning tonic. If his lungs were chronically bleeding already, it might be enough to send him on his way. I had one poison, swift and deadly and tasteless as water, if I could devise a way to be sure he would encounter it at a safely distant time. None of these were thoughts conducive to sleep, and yet the fresh air and the exercise of riding all day were usually sufficient to counter them, and I often awoke eager for the next day of travel.

When we finally sighted Blue Lake, it was like a miracle in the distance. It had been years since I had been so far from the sea for so long, and I was surprised how welcome the sight of water was to me. Every animal in our baggage-train filled my thoughts with the clean scent of water. The country became greener and more forgiving as we approached the great lake, and we were hard put to keep the horses from overgrazing themselves at night.

Hordes of sailing-boats plied their merchant trade on Blue Lake, and their sails were coloured so as to tell not only what they sold but which family they sailed for. The settlements along Blue Lake were built out on pilings into the water. We were well greeted there, and feasted with freshwater fish, which tasted odd to my sea-trained tongue. I felt myself quite the traveller, and Hands and I were nearly overwhelmed with our opinions of ourselves when some green-eyed girls from a grain-trading family came giggling to our fireside one night. They had brought with them small, brightly-coloured drums, each toned differently, and they played and sang for us until their mothers came scolding to find them and lead them home. It was a heady experience, and I did not think of Prince Rurisk at all that night.

West and north we travelled now, ferried across Blue Lake on some flat-bottomed barges I trusted not at all. On the far side, we found ourselves suddenly in forest lands, and the hot days of Farrow became a fond memory. Our path led us through immense stands of cedar, pricked here and there with groves of white paper-birch and seasoned in burned areas with alder and willow. Our horses’ hooves thudded on the black earth of the forest trail, and the sweet smells of the autumn were all around us. We saw unfamiliar birds, and once I glimpsed a great stag of a colour and kind I had never seen before or since. Night grazing for the horses was not good, and we were glad of the grain we had bought from the lake people. We lit fires at night, and Hands and I shared a tent.

Our way led steadily uphill now. We wound our way between the steepest slopes, but we were unmistakably making our way up into the mountains. One afternoon we met a deputation from Jhaampe, sent to greet us and guide us on our way. After that, we seemed to travel faster, and every evening we were entertained with musicians, poets and jugglers, and feasted with their delicacies. Every effort was made to welcome us and to honour us. But I found them passing strange and almost frightening in their differences. Often I was forced to remind myself of what both Burrich and Chade had taught me about the courtesies, while poor Hands withdrew almost totally from these new companions.

Physically, most of them were Chyurda, and were as I had expected them to be; a tall, pale people, light of hair and eye, and some with hair as red as a fox. They were a brawny people, the women as well as the men. All seemed to carry a bow or a sling, and they were obviously more comfortable on foot than on horseback. They dressed in wool and leather, and even the humblest wore fine furs as if they were no more than homespun. They strode alongside us, mounted as we were, and seemed to have no difficulty keeping up with the horses all day. They sang as they walked, long songs in an ancient tongue that sounded almost mournful, but were interspersed with shouts of victory or delight. I was later to learn they were singing us their history, that we might know better what kind of a people our prince was joining us to. I gathered that they were, for the most part, minstrels and poets, the ‘hospitable’ ones, as their language translated it, traditionally sent to greet guests and to make them glad they had come even before they arrived.

As the next two days passed, our trail widened, for other paths and roads fed into it the closer we came to Jhaampe. It became a broad tradeway, sometimes paved with a crushed white stone. And the closer we came to Jhaampe, the greater our procession became, for we were joined by contingents from villages and tribes, pouring in from the outer reaches of the Mountain Kingdom to see their princess pledge herself to the powerful prince from the lowlands. Soon, with dogs and horses and some sort of goat they used as pack-beasts, with wains of gifts and folk of every walk and degree trailing in families and knots behind us, we came to Jhaampe.