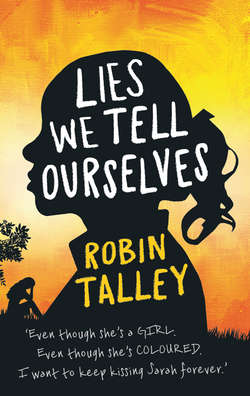

Читать книгу Lies We Tell Ourselves: Shortlisted for the 2016 Carnegie Medal - Robin Talley - Страница 10

ОглавлениеLie #2

MY ARM FEELS as if it’s being wrenched from its socket as I stumble through the crush of white people. The pain rockets through me, and my eyes flood with tears.

The grip on my arm lets go. I clutch at my chest as the breath floods back into my lungs.

Then I remember where I am. I turn to run.

“Sarah!” It’s Chuck. It’s only Chuck.

Ruth is next to him, staring at me with her forehead creased. The rest of the group is gathered behind them.

“Sarah, you all right?” Chuck says.

I nod. I can breathe again, at least. But we’re not safe yet.

The shouts are louder here than they were outside. They echo off the walls and high ceilings of the school vestibule, pressing in on us from all sides. More shouts come from deep inside the building. All around us, white people press in, shoving at our backs and glaring at our faces. The building looks huge from the outside, but the vestibule feels tiny with all these people packed so tightly into it, every one of them turned toward us.

Where are the teachers? The principal?

“Where do we go?” Ruth asks. I don’t know what to tell her.

“Mrs. Mullins gave me the list,” Ennis says. “Seniors go to the auditorium, juniors, the atrium, sophomores, the gym, freshmen—”

“The cafeteria,” Paulie cuts in.

“No way.” I’m not letting go of Ruth. Not again.

She pulls out of my grip anyway. She’s holding her head up again. Back to her old self.

“What are you going to do, babysit me all day?” she asks me.

“I’ll walk the freshmen over,” Chuck says. He nods toward Yvonne, who’s still rubbing her neck. There’s a red mark near her collarbone, but no blood. “I’ll watch out for them.”

I’m not sure about that. I don’t want my sister out of my sight.

But I don’t know what else to do. Ruth is right. I can’t be with her all day.

Plus, I don’t know where the cafeteria is. Or the auditorium, or anything else. I’ve never set foot in this building before, but Chuck is looking up and down the halls as if he knows his way around. I’ll have to trust him.

My heart thuds as I watch Ruth go to Chuck’s side, turn her back and walk away. All I can do is pray she’ll be safe.

Yesterday I would’ve thought prayer was enough. Today I’m not so sure.

“Come on,” Ennis says. “We’ve got to go. If we’re late we’ll get detention.”

I’ve never had detention before, but Mrs. Mullins told us the white teachers would look for any excuse to send us there. We can never be late to class, no matter what.

But if we have to deal with shouting crowds every day, won’t we always be late?

No. The crowd was only for today. Tomorrow things will go back to normal.

Whatever “normal” is at this huge, looming school, with the shining glass trophy cases lining every hallway and the brand-new books everyone is carrying. And the huge white boys in letterman’s sweaters lurking around every corner.

Somehow Ennis already knows his way around Jefferson, too, so I follow him. The auditorium isn’t far from the front doors, but it takes us a long time to get there because the white people are still swarming.

They’re still shouting, too. And throwing balls of paper. And sticking out their feet to trip us. One catches Ennis’s ankle and he falls hard, catching himself with his hands before his face hits the ground. It takes all my strength not to cry out when I see him going down.

The white people howl laughter as I help him up. Ennis is biting his lip and cradling his wrist. I pray it isn’t broken. If one of us comes home with a broken bone, the courts could say they were wrong and integration was too dangerous after all. They could send us all back to our old school. Daddy would be furious.

“Hey, you look real pretty today,” a girl says in my direction.

I turn around. Did one of the white people really say something nice to me?

No. Of course not.

The girl laughs at me and draws back. I can see what’s going to happen but there’s nothing I can do about it. The crowd is too thick for me to get away before the girl spits on the yellow flowered skirt Mama made for my sixteenth birthday.

I’m shaking again. Ennis looks at my skirt, then at me. He’s still holding his wrist.

“Come on,” he says. “We’re almost there.”

It’s getting hard to breathe.

Chuck will have to leave Ruth to come join us. It’ll be my sister and two other freshmen alone with all these angry white people. What if someone trips her like they did Ennis? What if she gets hurt, and she needs me?

Somehow Ennis knows what I’m thinking.

“You’ll only make it worse if you try to go back, Sarah,” he says, giving me that serious look again. “You’ve got to have faith it will be all right.”

I’m trying to have faith. It’s so hard. It’s the hardest thing I’ve ever had to do.

Chuck catches up with us at the auditorium doors. It’s too loud for us to hear each other, but he nods to tell me Ruth is all right.

She was all right when he left her, anyway. Who knows what might have happened since then.

A group of boys sings as we walk through the doors. The tune is a song that’s been playing on the radio lately, “Charlie Brown.” I used to like that song, but the boys have changed the words. “Fee fee, fi fi, fo fo, fum! I smell niggers in the auditorium!”

They howl with laughter at their own joke. Other boys and girls join in, snickering at Ennis and Chuck and me as we try to find seats. This room must be built to hold a thousand people. All the seniors are running back and forth between the rows, shouting, laughing, pointing at us. Teachers are standing around, too, but they’re talking to each other, looking at their watches, as if they haven’t even noticed we’re here.

“Two, four, six, eight!” The chant continues as the three of us move toward the front of the room. “We don’t want to integrate!”

Posters for school activities hang on the walls. Basketball practice. Science club meetings. Ticket sales for the prom. My eyes linger on a poster for Glee Club auditions before I remember we aren’t welcome at the clubs and teams and dances at this school. We aren’t even welcome to breathe the same air.

We find three seats together in the front row. I sit between Chuck and Ennis, trying to fold my coat so the spit on my skirt doesn’t show. Normally I’d feel uncomfortable sitting with two boys, but everything about today already feels strange.

We haven’t been sitting ten seconds when everyone else who was sitting on the front row stands up, all in one smooth motion, and files out.

For the second time this morning, I wonder if the white people rehearsed that.

“Boy, does it ever stink in here all of a sudden,” one girl says. Her friends laugh and pinch their noses.

Now that we’re alone in the front row, the chanting starts up again behind us. At first it’s just a few people, but then the rest of them join in. The voices get very loud very fast.

“Niggers go home! Niggers go home! Niggers go home!”

I look straight ahead. Ennis and Chuck are doing the same thing. I want to meet Chuck’s eyes but I’m afraid he’ll only try to make some awful joke, and instead of laughing I’ll burst into tears.

There is only one thing in this world right now that I want.

I want to get out of here. I want to get up, go find my sister and drag her out the front door. I don’t want either of us to ever set foot in this place again.

I’m starting to think things aren’t going to get better after this. I’m starting to think they’re going to get worse.

“All right now,” comes a voice. A teacher is on the stage, holding a clipboard. I wait for her to tell everyone to stop yelling and be polite and respectful, the way the teachers at my old school would have, but she just says, “All right,” again. Slowly, the chanting dies down.

The teacher looks bored. As if it’s any other first day of school. As if we aren’t starting five months late because the governor closed the whole school last semester to stop ten Negroes from walking through the front doors. As if there wasn’t almost a riot in the parking lot five minutes ago.

“Your senior class president will lead us in prayer,” the teacher says. She nods toward yet another boy with blond hair and blue eyes and a varsity letterman’s sweater.

“Let’s all bow our heads,” the boy says.

Automatically, my head goes down, my eyes shut and my hands fold in my lap. Before the prayer has even started, I feel something pushing on my lower back. Then the pressure gets sharper. Digging into my flesh through my thin cotton blouse.

Is it a knife? Am I going to die right now, right here? Before I’ve been to a single class in this godforsaken school? What will happen to Ruth if I die?

I’m about to leap out of my seat when I realize it can’t be a knife. A blade would be slicing into my skin, not just pressing.

This isn’t a knife. It’s a sharpened pencil point.

But it still hurts. A lot.

I ignore it and breathe deeply, trying not to let the pain distract me from my prayer as the blond-haired boy intones, “Our Heavenly Father.”

A second pencil joins the first, twin points drilling into me. I move forward in my seat, but the pencils move with me. They’re pushing deeper now. I wonder if I’m bleeding.

“You best pray hard, nigger bitch,” a boy’s voice says, low in my ear. “We’re gonna tear you to pieces first chance we get.”

That makes me shiver, but I don’t let the boy see. I move my lips along with my own prayer. Please, Father, watch out for Ruth today. And for me, and for all of us. Please watch over us and protect us and let us make it through safely. In Your holy name.

“Amen,” I say with the blond boy and the rest of the senior class. I open my eyes.

The stabbing pain is gone.

Even though I know better—and I’d have killed Ruth if she’d done this—I turn around. I want to see who gave me the bruises forming on my back. I want to meet his eyes.

There’s no one there. The seat behind me is empty. So are the seats on either side of it. The rest of the auditorium is a blur of identical-looking white faces.

Then I see a pretty girl with red hair and a stylish white Villager blouse a few rows back. She’s looking at me. But this girl isn’t sneering, or pinching her nose, or getting ready to throw something at me. She’s just looking.

She nudges her friend, another white girl with frizzy brown hair. The brown-haired girl sees me looking at them and puts her hand up in front of her cheek as if she’s embarrassed, but the red-haired girl isn’t shy about staring.

It takes me too long to realize I’m staring back at the red-haired girl.

I drop my head, but it’s too late.

Did she notice? Could she tell?

This hasn’t happened to me in a long time. Noticing a girl like that, and letting her see it. I’ve learned how to force it down when I feel those things. To act as if I’m normal.

But sometimes I can’t stop it. I can’t stop it now.

My cheeks are flushed. I feel off balance, even though I’m still sitting down. I grip the armrest to steady myself.

My mind is running to scary places. The images come too fast for me to stop them.

I imagine what it would be like if I were alone with the red-haired girl. How it would feel if she smiled at me with her pretty smile, and I smiled back, and—

No. I know better than to think this way.

I can’t take any risks. Especially not at this school. If anyone found out the truth about me it would mean—I don’t even know what it would mean. I only know it would be horrible. It would be a hundred times worse than what happened in the parking lot this morning. A thousand times.

Then I realize I’ve got another problem altogether.

The other white people have noticed I’m turned around. They’re whispering to each other and pointing at me.

The boys leer. The girls scrunch up their faces. One boy rolls a spitball.

I turn back around fast. I can’t make that mistake again.

I’d thought some of the white people at Jefferson might be all right. But if they were, they’d be helping us, wouldn’t they? They’d be telling the other white people to leave us alone. They’d have held the doors open so we could get through.

No one’s helped us yet.

The teacher is back at the front of the stage, still looking bored. “All right, seniors. It’s time to distribute your schedules and locker assignments for the year. When your name is called, go to Mr. Lewis or Mrs. Gruber to pick yours up. Then go straight to your first period class. There will be no dawdling in the halls. Tardiness will result in detention.”

“Want to bet she said that just for us?” Chuck mutters.

The spitball hits my back. The surprise of it makes me catch my breath, but I don’t let the white people see me flinch. Instead I reach back and pull the spitball off my blouse. It’s cold and slimy. It makes my stomach churn, but I tell myself it’s no worse than changing my little brother’s diapers, and I did that for two and a half years.

“Donna Abner?” calls a man standing in the aisle to our left. Mr. Lewis. His name was on the Glee Club poster, so he must be the Music teacher. A white girl moves up the aisle toward him.

“It’s alphabetical,” Ennis whispers as Mrs. Gruber calls for Leonard Anderson from the opposite aisle. “Sarah, you’ll be first, but come back here and wait for us after you get your schedule. We’ll all go to first period together.”

“What if we’re not in the same class?” Chuck asks.

Mrs. Mullins said the school might put us in different classes. If we were separated, the school officials thought, there’d be less risk of violence. I guess they thought two or three Negroes together would try to take on an entire classroom full of whites. As if any of us wanted to get killed.

“We’ll walk together anyway,” Ennis says. “The longer we’re together the safer we are. That’s more important than detention.”

But when the teachers reach the D’s, they skip right over where my last name, Dunbar, should be and go straight from Thomas Dillard to Nancy Duncan.

Should I say something? I look at Ennis.

“Let’s wait,” he whispers.

When they get to the M’s, when Ennis should be called, the teachers skip over him, too. The same thing happens with Chuck when they get to the T’s.

Maybe this was all a big mistake.

We were told we’d been admitted to the school, and that we should come in today along with the white people, but maybe the courts have issued a new ruling. Maybe the police will troop in to pull us out of here. The white people will line the halls and cheer as we’re escorted from the building.

The auditorium is almost empty now. Somehow it’s scarier seeing just a few angry white faces staring us down instead of a hundred. If they got one of us alone they could do anything they wanted and it would be their word against ours.

Finally the last name, Susan Young, is called. Mr. Lewis gives Susan her schedule. Once her back is turned he comes over to stand in front of Ennis, Chuck and me.

The rest of the teachers have left. Mr. Lewis leans back and rests his elbow on the stage, looking us over.

My heartbeat speeds up. Mr. Lewis is a teacher, but that doesn’t mean he supports integration. Would he do something to us if it meant risking his job? Not that anyone would believe three colored children telling stories about a grown white man.

Then Mr. Lewis smiles.

I tilt my head, confused. It looks like a real smile, not a sneer.

“Hello,” he says. “Welcome to Jefferson High School.”

Is this a trick? Next to me, Chuck shifts in his seat. There’s suspicion in his eyes.

Mr. Lewis looks at each of us in turn, still smiling. “I’m told you three will be the first Negroes to graduate from a white school in Davisburg County. All I can say is, it’s about time.”

Oh.

It’s the first kind thing anyone has said to us.

I try to smile back at Mr. Lewis. Mama would want me to be polite.

“Let’s get you some schedules.” Mr. Lewis pulls three rumpled papers from his pocket. “Sorry we didn’t have them with the others. Apparently someone in the office didn’t think you’d be here today, so your schedules had to be assembled rather hastily.”

He chuckles. I don’t. We might very well not have been here today. Some of the white parents tried to file an emergency petition at the courthouse just yesterday to stop us from getting into Jefferson.

The white parents, and the school board, and Senator Byrd and Governor Almond fought this with everything they had. It’s been five years since the Supreme Court said integration had to happen, but for five years, the white people kept fighting, and our schools stayed segregated. Until last week, when the courts put out their final ruling: the white parents, and the governor and the rest of the segregationists had lost.

Here we are. Whether they like it or not.

Whether we like it or not, too.

“Miss Dunbar.” Mr. Lewis hands me a paper.

No one ever calls me “Miss.” Usually it’s just “Sarah.” Or, if it’s a white person talking, “Girl.”

He hands Chuck and Ennis their schedules, too. I try to read the scrawled handwriting on mine.

* * *

Typing? I took Typing at my old school. And I’ve already had two years of French. Plus there’s no music class on my schedule at all. At my old school, Johns High, I was going to take Advanced Music Performance this year.

“What do these R’s after the course names mean?” Chuck whispers. I look at his schedule. He has the same first-period Math class I do. Other than that, we don’t have any classes together.

I don’t know what the R’s mean, either. I want to ask Mr. Lewis, but Ennis is already standing up.

“Come on,” he says. “We don’t want to be late. Thank you, sir.”

“Go straight to your first-period classes,” Mr. Lewis says. “There’s no Homeroom today. Good luck.”

Good luck? I wonder if he’s joking.

We file out of the auditorium in silence. Someone has shut the doors, even though the assembly only just ended. Ennis pushes them open and steps out into the hall.

“There they are!” The cries are coming from all around us. At least a dozen boys are gathered, most in letterman’s sweaters. “There’s those coon diggers!”

“You have to go to the second floor?” Ennis mutters to me, not taking his eyes off the boys. They’re coming closer. They’re smiling.

“Yes,” I whisper. “Chuck does, too.”

“You go first, Sarah,” Chuck says. His voice is low and gravelly. “We’ll keep them from following you.”

“If we separate they’ll only split up and follow us all,” I whisper.

I wonder if Mr. Lewis knew this would happen. If that’s why he kept us late. I want to trust him, but it’s hard to trust anyone in this place.

“What’re you doin’ here, niggers?” one of the boys says. “You know you don’t belong in our school.”

“It’s our school, too,” Chuck says. “So what are you doing here?”

That sets the boys off. Two of them run at Chuck.

“Hey!” comes a loud voice behind us. Mr. Lewis. The boys stop in their tracks. “What’s this about?”

“That one started it,” one of the boys says, pointing at Chuck.

“He didn’t,” I say. “He wasn’t doing anything, he—”

Mr. Lewis raises his eyebrows at me. “Young lady, I think you and Mr. Mack had better get to class. Charles, Bo, Eddie, come with me.”

“But—”

Ennis takes my arm and pulls me away before I can finish.

“What will happen to Chuck?” I whisper when we’re far enough away. Behind us Mr. Lewis is leading Chuck and the two white boys who charged him toward the front office.

“Probably nothing,” Ennis says. “That teacher got there before anything happened. He’ll get a lecture, that’s all.”

“Will anything happen to the white boys?”

“No way.”

We’re walking up an empty staircase. Ennis is looking around in every direction, and I remember I’m supposed to do the same thing. We have to be extra alert in the stairwells. In Little Rock that’s where they set off the firecrackers.

“Keep an eye out for Ruth, will you?” I ask Ennis. “If you see her in the halls, make sure she’s all right?”

“I’ll try.”

Ennis leaves me at my classroom door, walking as fast as he can down the hall. I hope he doesn’t run into any other white boys.

I hadn’t thought much about Ennis before this morning. Chuck was in my group of friends back at Johns, but Ennis mostly kept to himself. After the way he helped Ruth in the parking lot, though, I’m going to be watching out for him, too.

The door to room 218 is closed. I’m scared to push it open, but if I don’t I’ll get a tardy slip. So I take a long breath, say a quick prayer and open the door.

Inside the room it’s dead silent. Then, as one, twenty heads jerk up. Twenty white faces gaze up at me. The door latches closed behind me like a gunshot.

I want to drop my eyes. Instead I look out into the sea of faces. Every one is looking back at me.

First come the stares.

Next, the pointing and the whispers.

Last, and most frightening, are the grins.