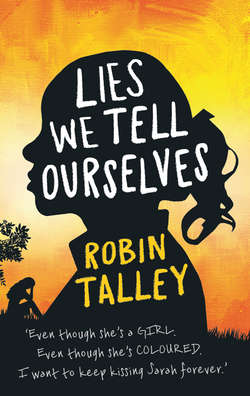

Читать книгу Lies We Tell Ourselves: Shortlisted for the 2016 Carnegie Medal - Robin Talley - Страница 13

ОглавлениеLie #5

MY AFTERNOON CLASSES are no better than the morning’s. In Home Ec the teacher gives me my own set of pans and bowls and silverware to use for the whole semester so the white girls won’t have to touch the same things I do. In Study Hall I sing hymns in my head while the boys make honking noises at me and the teacher takes a nap at his desk. In Remedial English our textbook reader doesn’t have any stories longer than fifteen pages, except for one by James Joyce that my mother gave me to read when I was twelve.

I’m the only Negro in every class.

Halfway through sixth period I start counting the number of times I hear people call me a nigger. By the time the bell rings at the end of the day I’m up to twenty-five.

Chuck and Paulie, the only junior in our group, are a short way down the hall when I come out of my last class. They’re walking so fast they’re almost running. Behind them a group of white boys is walking even faster.

I can tell from the looks on their faces that the white boys aren’t playing. As soon as we’re off school grounds they’re going to do whatever they want to us.

“Downstairs, side exit,” Chuck mutters when they reach me. “The NAACP’s got cars waiting for us.”

I struggle to walk as quickly as Chuck and Paulie as we head for the stairs, but my breath is coming fast, and my sweaty feet are sliding in my loafers.

“What about the others?” I ask.

“Everyone knows where to go. Ennis is spreading the word.”

I pick up my pace and try not to worry about Ruth. Ennis will make sure she’s all right.

All around us, more white people spill out of classrooms. Some of the boys join the group following us. I want to look over my shoulder and see how many are back there, but if they see me looking it will only make things worse.

Besides, I can tell the crowd is growing by the number of niggers I hear. My count is already up past forty.

I scan the hallway for a teacher, but there are none in sight. And if I did spot a teacher there’s no way to know if she’d help. The stairs are still a long way off.

“They’re only trying to scare us,” Chuck whispers.

“It’s working,” Paulie whispers back. He looks paler than I’ve ever seen him.

“Don’t talk that way,” I say.

We don’t know who might be listening.

Ahead of us, in front of the stairwell there’s another, bigger, crowd, also shouting taunts. Strangely, though, this group has their backs to us. They don’t even seem to know we’re coming. They’re gathered around something lying on the floor.

No. Not something. Someone.

I break into a run. Chuck calls out for me to wait, but then he must see what I’m seeing, because the hard soles of his shoes come pounding down the hall behind me.

The boys following us have started running, too.

The shouts coming from the group ahead are the loudest they’ve been since we made it inside the school. They’re so noisy I want to clap my hands over my ears.

I can’t. Not until I know who they’re shouting at.

“Somebody show that girl this ain’t no school for coons!” someone shouts.

“We’re gonna teach her a lesson!”

So it’s a girl. I want to pray for my sister’s safety but my thoughts are racing too fast for prayers.

“Look at her all bent over like that,” someone else says. “That nigger’s fatter than Aunt Jemima!”

“Go back to the cotton field, you ugly burrhead!” a girl shrieks.

Chuck gets to the crowd first. I’m right behind him as he pushes through the group to the center of the circle. I spot a pink skirt hem crumpled on the floor.

It isn’t Ruth. To my shame I breathe a sigh of relief.

It’s Yvonne. She’s crouched on the ground in the middle of the crowd, facedown, her hands folded over her head and her knees tucked under her.

It takes me a second to piece together what happened. Someone must have tripped her, and she couldn’t get up right away in the midst of that huge crowd. Instead she hunched down to protect herself from being kicked. It doesn’t look as if she’s badly hurt, not yet, but the longer she stays where she is the more likely something is to happen.

She’s trapped in the middle of a crowd that’s getting bigger with each passing second. The boys who’d been chasing us have merged with it. There must be fifty of them surrounding her, jeering and throwing pennies. There’s spit all over Yvonne’s dress. Some of the boys are winding their legs back like they’re about to kick her.

Chuck reaches the middle of the circle first. He leans down and says something to Yvonne that I can’t hear over the shouting. The white boy nearest him, a greaser with slicked-back hair, kicks out at Chuck, but Chuck sees him in time and lunges out of the way.

That only makes the boy angrier. He’s backing up to deliver another kick when a woman’s voice booms, “Everyone move along, now!”

The shouting dies down fast, but no one moves. Not until the teacher, a gray-haired woman I don’t recognize, comes into the middle of the circle. When she sees Yvonne huddled on the floor she recoils.

“One of you, go to the office and call for a doctor!” she says.

The white girls nearest me turn and run. Within seconds, all the other white people have gone as fast as they came. The four of us Negroes and the gray-haired teacher are the only ones left in the hall.

I kneel on the floor. Chuck is still bent down, trying to say something in a low voice, but Yvonne hasn’t moved. I catch his eye and whisper, “Let me try.”

He shrugs and stands up. The teacher takes him aside to ask a question. I want to talk to the teacher, too, but I need to focus on Yvonne. Ruth could get here any second and I don’t want her to see her friend like this.

“They’re all gone,” I tell Yvonne. “You can get up. I’m here, and Chuck and Paulie, too. You’re not by yourself anymore.”

After a long second, she turns her head and meets my eyes. Hers are wet.

“They tripped me,” she says.

“I know. Are you bleeding at all? Did you get hurt when you fell?”

“I don’t think so. My knee hurts a little. There were so many of them. I was afraid to get up. I thought they’d never leave me alone if I—”

“I know,” I say. “It’s all right. It was smart, what you did. Can you stand?”

Slowly, Yvonne uncurls from her crouch. She lifts her head and looks around the hall. When she sees we really are alone she lets me help her up. Dust and dirt are all over her clothes, and her face is streaked with tears. She winces when she puts her weight on her right leg.

I reach out a hand to help her up. That’s when I notice I’m shaking harder than she is.

What if the teacher hadn’t gotten there when she did? Yvonne could’ve really been hurt. Or Chuck could’ve.

It could have been any of us.

I look around for the others. Paulie is standing against the lockers, pressing his fist into his forehead. Ennis is here, too, talking with Chuck and the teacher. Chuck looks angry. The teacher is nodding at Ennis, who’s saying something in a low, serious voice.

“All right,” Ennis says to all of us after a minute. “We’ve got to go fast. The others are waiting for us by the side exit at the bottom of the stairs.”

“Are they safe?” I ask.

“They were when I left them.”

That doesn’t make me feel better.

Yvonne’s knee is worse than she’d thought, so we have to move slowly. I want to run ahead to see Ruth, but that wouldn’t be right. I’m the only other girl here, so I have to let Yvonne lean on me as we make our way toward the stairs.

At least Ruth isn’t alone. I’ll see her soon. As soon as I possibly can.

“What did the teacher say?” I ask Chuck as we navigate the stairwell. Yvonne flinches on every step.

“She wanted to call a doctor to come look at Yvonne. Ennis talked her out of it. He said she’d be safer if we could get her to Mrs. Mullins’s first.”

I think Ennis is right, but from the set of Chuck’s jaw I can tell he disagrees.

When we finally get to the side exit Ruth is waiting for us just inside the door with the other freshmen and sophomores. One of the younger girls is crying. Ruth has her arm around her.

I want to gather Ruth into my arms and never let go. Instead I motion for both girls to walk with me and Yvonne.

“That’s enough of that, now,” I tell the crying girl. “We have to move.”

Ruth glares at me. I ignore her.

The four of us will be the first ones outside. Through the narrow window we can see the crowd gathered around the door, waiting for us. We have no choice but to walk right into the middle of it.

“Can you get them to the curb?” Ennis whispers to me. His forehead is creased, but we both know it’s better this way. The boys should be at the back of the crowd this time, where the rowdiest white people will be. “The cars are waiting. Get in the first one. It’s Mr. Stern driving.”

I nod. “What about everyone else?”

“We’ll be right behind you.”

He says something more, but I can’t make out the words. As soon as we step outside the doors the noise from the crowd is deafening.

I can’t see any faces now, or hear any voices. It’s all a blur of white and hate.

I want to run, but the crowd would just run after us. As soon as we’re off school property, they’d catch us. I don’t want to think about what would happen then.

So I walk as fast as I can, and I make the others do the same, even though Yvonne is groaning from the pain in her knee. She and I are in front, with Ruth and the other girl behind us. I can see Mr. Stern’s car up ahead. Ennis was right—it’s probably the safest of the NAACP cars for us to take. No one will think we’re aiming to get into a car with a white man.

The white people are swarming us from all sides now. It’s as bad as it was this morning.

No. It’s worse. This morning the white people just looked furious. Now they look like killers.

“Get the niggers!” A chant starts up. “Get the niggers! Get the niggers! Get them!”

They’re right up in our faces. After a full day of this their glares and shouts aren’t shocking anymore. I’m used to the feeling of my heart throbbing in my chest, my eyes sharpening, my shoulders quaking with fear.

Police officers line the curb. I don’t expect any more help from them than I did this morning.

I glance over my shoulder to see the other girls and almost trip, catching myself at the very last second.

This won’t work. I can’t walk in front of them and make sure they’re safe at the same time.

Ruth catches my eye and nods. It feels like a terrible mistake, but I move behind the others and let Ruth take the lead.

This is the most frightened I’ve been for her all day, but there’s nothing I can do. Ruth marches through the crowd, her head high, her gaze straight ahead. The white people scream at her but they move aside, like she’s Moses parting the waters.

This time, when someone spits on her hand, she ignores it and keeps on walking.

It makes me want to cry. Instead I keep my eyes dry and fixed, letting Ruth lead us.

They’re still shouting. I sing to myself in my head to drown out their words. An old hymn. The old ones are always the best.

Rock of Ages,

cleft for me,

let me hide

myself in thee.

Something sails over Yvonne’s head. A ball of paper with something heavy wrapped inside.

I don’t say anything. I don’t think she noticed. I can’t tell whether the white boy who threw it was only trying to scare us or if he just has bad aim.

The chant has changed now, back to the familiar “Two, four, six, eight, we don’t wanna integrate.” We’re almost at the curb. Mr. Stern is waiting in the car with his engine on.

It’s over. Soon we’ll be out of this place. We’ve survived. This day is finally at an end.

Ruth opens the back door and climbs inside, moving over so Yvonne and the other girl can slide in. I get in the front seat with Mr. Stern.

With the windows rolled up we can barely hear the chants. It really is over. Mr. Stern steps on the gas.

But just as he’s turning the wheel, the back door on the far side—Ruth’s side—jerks open. A grown white man with a wide chest and huge hands is standing by the side of the car, holding on tight to the door frame and looking right at Ruth.

“Get out of the car, niggers, before we drag you out,” the man’s voice booms. “You, too, you nigger-loving Jew.”