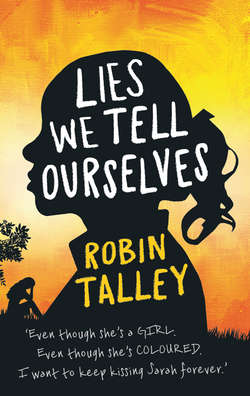

Читать книгу Lies We Tell Ourselves: Shortlisted for the 2016 Carnegie Medal - Robin Talley - Страница 17

ОглавлениеLie #8

THEY CANCELED THE prom today.

Because of the colored people. Everything that happens now is because of the colored people.

If Daddy has to work late at the paper it’s because the integrationist teachers are making up stories. If I’m behind in English it’s because the NAACP forced the school to close last semester. If I get caught daydreaming in Math it’s because the colored girl in the front row distracted me.

But the prom? Why did they have to get that, too?

I was going to the prom with Jack. It was going to be my last date of high school, and the first time Jack and I went to a dance together. Jack is far too old for these sorts of things—he’s twenty-two—but he said he’d come anyway. He said I shouldn’t have to miss out on my own prom just because my fiancé is an older man who’s long past childish stuff like school dances.

“I don’t see why they had to cancel in the first place,” Judy says. She has to raise her voice for me to hear her. There’s noise up ahead. People shouting. There’s always shouting in the halls now that the colored people are here.

We’re walking down the hall toward the first-floor bathroom near the stairwell. It’s the only bathroom Judy ever wants to go in because it’s always empty and she can fix her makeup without anyone seeing. The toilets in that bathroom have been stopped up since our freshman year.

“It’s obvious,” I say patiently. You have to be patient with Judy. She’s not slow like people think. She’s naive, that’s all. “No one wants white people and colored people dancing together.”

“Would that really happen?” Judy says. “Was someone going to force us to dance with them? Wouldn’t the coloreds only dance with each other?”

“Coloreds isn’t a word,” I tell her for the hundredth time. I swerve to step around a group of giggly sophomores. People are so rude, blocking the halls like this. They think just because our school is integrated they all have the right to act like animals.

“Right,” Judy says. “Sorry. The Nigras, I meant. But wouldn’t they?”

“Who knows what would happen,” I say. “No one thought we’d be forced to let them into our school. It’s not as if they didn’t already have their own. If they weren’t happy going to school with each other, why should they be happy dancing with each other?”

“Oh,” Judy says. “I hadn’t thought about it that way.”

I picture the shiny blue dress in my closet. It’s strapless, with a matching blue wrap and blue high heels. It looks almost as good as the fancy one from Miller & Rhoads I modeled in the Future Business Leaders of America fashion show last year. Mom took me shopping for it the day they announced the schools were going to reopen. She said it was too bad about the integration, but at least I wouldn’t have to miss out on all the fun of my senior year.

Daddy was furious when he found out. He said I wasn’t going to any dance with any colored boys. I told him I wasn’t going with a colored boy, I was going with Jack, and besides, it wasn’t my fault the governor gave up on segregation. Daddy said as long as I was under his roof I would speak to him respectfully, and I said then it was a good thing I wouldn’t be under his roof much longer. Then he pulled back his hand. For a second I thought he was going to do it. I think he thought so, too.

I almost wanted him to do it. To prove I still mattered to him even a little bit.

But he didn’t. He put his hand down and said I was an ungrateful little girl and he had work to do. Then he went to his study and didn’t come out again all night. As though he’d forgotten I was out there.

Mom told me to keep the dress because you never knew. Daddy had been known to change his mind about things. Then she disappeared upstairs with a glass of sherry and I was alone again.

The noise is getting louder as we near the stairwell. “We’re gonna shut that nigger up!” a boy yells.

Oh, for heaven’s sake. This again?

“That looks like a colored girl they’ve got there,” Judy says. The shouting is so loud I have to strain to hear her.

“A girl?” I say. “Who’s got her?”

“Bo and his gang, I think.”

I could’ve guessed. Bo Nash and his friends are a bunch of nobodies. Or they would be, anyway, if Bo hadn’t scored two touchdowns back-to-back sophomore year. He went from no-good redneck farm boy to town hero in one night. It only got worse that spring, when he pitched a no-hitter for the baseball team’s state championship. Girls stopped joking about Bo’s dirty, mismatched socks and started cooing about his dreamy blue eyes. It was enough to make you vomit. Now Bo thinks he owns the school. And everybody else seems to think so, too.

Well, not me. Any boy who wants to beat up on a girl, colored or not, isn’t worth the sweat in his undershorts. Bo’s a star of the team, so I can’t be outright nasty to him—not unless I want to hear everyone whispering about me in the halls all year—but I can take him down a peg or two.

Bo is right up in front of the colored girl when I get there. He and his friends have got her backed into a corner. She’s turning her head this way and that, looking for a way out. It’s one of the younger ones. Her white blouse has an ink stain on it, and her brown skirt is old and patched.

I stride up to the group and step in neatly between the boys and the girl, facing Bo. He scowls at me. Behind us, people are yelling, and another girl is screaming. I hold out my hands the way Reverend Pierce does when he’s trying to get an especially rowdy congregation at Davisburg Baptist to sit down and be at peace already.

“What’s the matter, Bo?” I ask, raising my voice so everyone can hear. “You’ve got everybody all riled up. For a second I thought Elvis came to town.”

A bunch of people laugh. I smile, because I know it’ll make Bo mad. I haven’t forgotten what he said to Judy in French yesterday. If he thinks he can get away with treating my best friend like that, he’s even dumber than I thought.

“You best just get on out the way, Linda,” Bo says. “We’re teaching somebody a lesson.”

I look over my shoulder in fake surprise, as if I didn’t know the colored girl was there. She’s cowering against the lockers. I take my first good look at her. Her eyes are wide and shockingly white around her deep black irises. The sleeves of her blouse have been let out so far the frayed edges are showing. She probably lives in one of those falling-down shacks out in Clayton Mill. My brothers say those places are full of lowlifes and it isn’t safe for a girl like me to go near them.

The colored people are all poor as dirt. They look it and smell it, too. Everyone says so.

I turn back toward Bo. “Right,” I say. “Because picking on some dumb, dirty little colored girl takes you and twenty of your friends.”

There’s more laughter behind Bo. The girl who was screaming before has stopped, thank the Lord. Everyone is watching me.

“She talked down to Gary’s girl,” Bo says, nodding toward the black-haired boy behind him. “She needs to learn her place.”

“Gary has a girl?” I’d heard that—Gary started going out with that freshman Carolyn, because everyone says she’ll go all the way with anyone who gives her his football pin—but I pretend I haven’t. “That’s really nice, Gary. Maybe we can double-date sometime.”

“Well, sure, Linda,” Gary says, smiling as if it’s a sunny Sunday afternoon, and there isn’t a scared little colored girl hiding behind me in the hallway. All the boys on the team want to go on double dates with Jack and me. “That’d be swell.”

Bo isn’t smiling.

“I’m not joking around, Linda,” he says. “You got to get out of our way. I don’t like to push a girl, but—”

Unless she’s a colored girl, apparently. I lower my voice so only Bo can hear. “I’m sure you didn’t just threaten me, Bo. Because if you did, you know Coach Pollard will hear all about it.”

Bo cocks his head to the side. His face slackens. I’ve won.

I raise my voice again.

“I thought you all might like to know Principal Cole is right around the corner,” I lie. “I saw him on my way from English. Maybe you don’t care, but I just figured I’d mention it...”

The boys back away. Everyone knows the new rule about fighting. No one’s talked about anything else all day.

My father thinks the rule is absurd. He told Mom and me all about it last night. He’ll have an editorial out tomorrow about how we need to teach our children personal responsibility, instead of harshly disciplining boys for being boys. Once the people of Davisburg have read what he has to say, he told us, he expects the policy to be reversed promptly.

“Don’t you do that again, Linda,” Bo says under his breath before he fades away with the rest of his group.

“Aw, Bo, I’m just teasing,” I reply, just as low.

I hope he believes me. I don’t have a bit of respect for Bo Nash, but he’s not someone you want mad at you, either.

When I turn around, the little colored girl is gone. I guess she went to her class. We only have two minutes left before French, but Judy still needs to do up her makeup, so we go into the bathroom.

Judy scrubs her face clean, grabs her compact and gets to work, moving so fast she’s going to leave streaks. I’m about to tell her to fix it when the door bursts open and a girl rushes past us and crouches on the floor. It’s another colored girl.

Judy drops her compact she’s so shocked. I’m surprised, too. We used to come in this bathroom between classes every day last year, and not once did anyone else come in.

“What are you—” Judy says, but I hold up my hand for her to let me handle this.

“You’re not welcome here,” I tell the girl, who’s not looking at us. I’m not sure she even noticed we were in here. It’s not the same colored girl Bo was after, so I don’t know why she’s making such a fuss. “We were here first.”

The girl doesn’t seem to hear me. She’s fallen down on her knees on the tiles, her head bent.

Oh, no. She’s praying.

I can’t interrupt a girl who’s praying. Even a colored girl.

Why does she have to pray in the bathroom? They have colored churches, don’t they?

Why does she have to come where I am in the first place? And why did that other girl have to go where Bo and his friends were waiting? It’s utter foolishness. If the school had to let them in, they should’ve picked some other section of the building where the colored people could go so the rest of us wouldn’t have to see them, the way they did at the bus station.

Or smell them. I sniff the air to see if the girl has made the bathroom stink yet. So far it’s just the usual smell of disinfectant and old paint, but she hasn’t been here long.

Judy looks at me, waiting for me to tell her what to do, but I don’t know what to say. When someone’s praying, you’re supposed to be quiet and respectful. But those are the rules for white people. Are they the same for Negroes? It’s so hard to keep track.

There’s still another minute until French, and Judy isn’t done with her makeup yet. I gesture for her to keep working on her cheek. She turns back to the mirror.

There’s something wrong with the colored girl. Her lips are moving quickly but silently, and she’s rocking up and down. She’s crying. I wonder what’s upset her so much.

If Daddy ever finds out I was in a bathroom with one of them, by choice, he’ll let his hand fly after all.

The girl goes on praying for a long time. She looks familiar. I must’ve seen her before, but it’s hard to tell them all apart.

Then I remember. This girl is the one from French. The one who called me “awful.”

She’s the worst of the whole lot.

Why did she have to run in here, out of all of them? Why do these colored people have to keep making my life harder?

Finally the girl stops rocking. She keeps her head bowed and her eyes shut, but her lips aren’t moving anymore.

It’s strange seeing a colored person so close up. Her hair is straight, but it looks rough and coarse. Not like my hair or Judy’s at all. And her skin is so dark. Much darker than mine gets even after I’ve been out in the sun for months. Touching her probably feels like touching sandpaper. Not that I’d ever touch colored skin.

It would be all right for us to leave now. God would understand. The truth is, though, I want to know what’s wrong with this girl.

I’m just curious. Who wouldn’t be?

And it doesn’t matter if I’m a tiny bit late to French. None of the teachers ever give me detentions, not if they want to get invited to the Christmas parties. My mother has been president of the Jefferson PTA since my oldest brother was a freshman.

“Are you all right?” Judy asks the girl when she finally opens her eyes.

I glare at Judy. She whispers an “Oh” and looks apologetic.

Judy never remembers you’re supposed to act differently around different people. If it weren’t for me, she’d talk to this colored girl the same way she talks to Reverend Pierce.

The colored girl doesn’t show any sign of having heard Judy. She’s looking down at her clothes. I wonder if she’s checking for stains. This morning I saw one of the other colored girls get sprayed with ink outside the library. Everyone was laughing. It made me think of the time Eddie Lowe pushed me into a puddle in second grade when I was wearing my new Easter dress. I got so upset Daddy wrote an angry letter and Eddie’s father sent us a check for five dollars to buy me a new one.

The girl this morning didn’t look upset, though. She just kept walking with her head held up so high I wanted to look around for her puppet strings.

“I’m leaving,” this colored girl says, standing up.

“You don’t have to,” Judy says. “No one ever comes in this bathroom. If you want to be alone—”

Judy stops talking when I shake my head at her. It’s one thing to show basic human decency. It’s another to go out of your way to accommodate someone who’s trying to change our whole way of life.

I wrote an editorial about that for the school newspaper last year. I said if the integrationists won, the rest of us should behave like civilized people, but we shouldn’t feel obligated to act happy about things.

Daddy liked that column. Or anyway, Mom told me she thought he probably did.

The colored girl is looking at Judy, her head tilted. Even with her dark skin and old, patched clothes, the colored girl is pretty. She has long hair, longer than the style is now, and her eyes are wide and dark.

It’s strange. I’ve never thought of a colored girl as being pretty before. My friends whisper sometimes about how a few of the colored boys look all right, but everyone says that’s because so many of them are tall and muscled from working outside. I don’t know what would make a colored girl nice looking, exactly. But then, I’d never seen a colored girl up close before yesterday.

“Do you need—?” the colored girl starts to ask Judy. Then she stops. Judy cups her hand over her cheek, and I realize what the girl is looking at. Judy never finished fixing her makeup. The colored girl saw her birthmark.

Judy takes out her makeup case and hurries to brush more onto her face.

“Never mind,” the colored girl says. “I’ll be leaving now.”

“Good.” I tug Judy’s elbow. “You can leave the whole school while you’re at it, and take your friends with you. Hurry up, Judy, we’re already late.”

“Are you all right?” Judy asks the girl as she sweeps on more makeup. “You were crying. And—praying.”

“Don’t talk to her, Judy,” I whisper.

The colored girl looks at me, tilting her head to one side. I look back just as fiercely. What gives her the right to stare at me?

She looks like she’s thinking hard. Deciding something. Finally, she opens her mouth. When she speaks, it’s slow, like she’s measuring each word before she says it.

“Since when do you care about being polite?” the colored girl says.

Judy gasps. I would, too, except I can hardly breathe at all.

I can’t believe she spoke to me that way.

No one speaks to me that way.

No one who’s not related to me, anyway. Certainly not a Negro.

Who does this girl think she is?

And after I just finished helping that other colored girl, too. If it weren’t for me that little girl would be splattered all over the lockers by now.

Daddy was right. The Negro students think they’re entitled. They think their own schools—the ones set aside specifically for them—aren’t enough. They think they have to come to our schools, even if it means hundreds of us have to suffer just so a handful of them can be satisfied.

The colored girl smiles. As though she’s proud of herself.

“I didn’t ask you to come to this school,” I tell her.

A corner of the girl’s lip turns up.

Is she laughing at me?

“I’ve got you figured out,” she says. “You’re Linda Hairston, aren’t you? Your father is William Hairston.”

“Yes,” I say. Everyone knows that. I don’t know why this girl is acting as if knowing it makes her special.

“You were the one talking to that gang of white boys. You called my sister dumb.”

Oh. I try to remember if I heard anything about two of the integrators being sisters, but I don’t think the paper said anything except that there were ten of them and they’d all claimed they weren’t Communists.

“So why did you get in front of her in the first place?” the girl asks me. “Some sort of stunt to show that your father isn’t the monster his editorials make him out to be?”

“My father’s no monster,” I hiss.

But I do wonder why I got between Bo and that girl. I was mad at Bo, sure, but I could’ve just made fun of him in the cafeteria or something instead.

I guess it just didn’t seem right, what Bo was doing. A whole group of boys, going after a little freshman girl.

And there was something about the little girl’s face, too. She looked so afraid. It didn’t seem right that she had to be so scared just because she was a Negro. She couldn’t help her color.

She could help being an agitator, though. She shouldn’t have been stirring up trouble at our school. What happened to her was her own fault. I’m too softhearted for my own good.

What bad luck, that I had to run into her older sister right after. I glare at the girl. She glares back at me and shakes her head.

“I’ve read your father’s editorials,” the girl says. “Looks as though you both like to tell everybody else what to do. Especially us Negroes.”

“Nobody’s telling you what to do,” I say. “Your people are the ones telling us what to do. If you’d just let things be, we’d all be better off, your people and mine both. Your sister wouldn’t have gotten in trouble in the hall today and needed my help.”

I try to emphasize that last word, help, so this girl will know she should be thanking me, not arguing, but she doesn’t look especially thankful. When she speaks again, her words are still slow and deliberate.

“All my sister and I are trying to do is go to school,” she says. “We should be able to do that without having to worry about people coming at us in the halls.”

“You already had a school to go to,” I point out. “A school that’s been open all year long. Your prom didn’t get canceled. I bet you’re happy to have ruined it all for the rest of us, though.”