Читать книгу Clarence Thomas and the Tough Love Crowd - Ronald Suresh Roberts - Страница 17

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Julien Benda’s Politics

ОглавлениеWhen Julien Benda flaunts his credentials he does so as the savvy Machiavellian, not the donnish recluse. Benda berates his opponents for political clumsiness, not hapless truth finding: “Modern equalitarians, by failing to understand that there can be no equality except in the abstract and that inequality is the essence of the concrete, have merely displayed the extraordinary vulgarity of their minds as well as their amazing political clumsiness.”

Likewise Stephen Carter criticizes the reasoning in Roe v. Wade, not primarily for its analytical defects but because it “stands out as a political failure.” Roe is, for Carter, a political failure because of the persistence of open opposition to the decision. Carter’s message is that if your political goals will occasion open and resilient opposition, you should adjust your ideals: “One receives only imperfect justice in the world; only fools, children, left-wing Democrats, social scientists, and a few demented judges expect anything better.”

This language is the epigraph of an article that is the cornerstone of Carter’s constitutional theory. The passage is, ironically, the invented speech of a fictional judge in Walter Murphy’s novel The Vicar of Christ. Carter concedes that the judicial restraint—apolitical, somehow nonactivist deci-sionmaking—counseled in his epigraph is a “sad and somewhat unfashionable philosophy” among lawyers.5 So, in order to manufacture the harsh truth about judges that we all ought afterward to face, Stephen Carter turns to fiction. Carter’s counsel of judicial restraint is harsh prescription rather than dispassionate description. For Benda and the Tough Love Crowd, the thinker ought to peddle opium to the masses. Benda applauds the Church for grasping “that love between men can only be created by developing in them the sensibility for the abstract man, and by combating in them the interest for the concrete man; by turning them towards metaphysical meditation and away from the study of the concrete.”

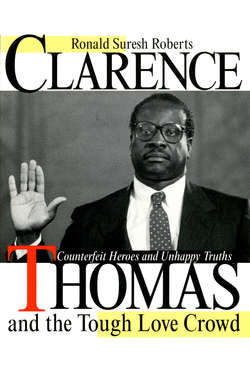

This robust agenda is rather a long way from the disinterested, insular musings with which we began. A legal-constitutional version of Benda’s view can, moreover, be found in the Tough constitutional doctrine of original intent. Clarence Thomas has referred favorably to an original-intent picture of the Constitution in which “equal opportunity—with all the inequalities of result this necessarily produces—was the goal, and the Declaration of Independence was the guide.” Thomas elsewhere wrote that this true equal opportunity America, the one with necessary inequalities, has been hijacked: “The tragedy of the civil rights movement is that as blacks achieved full exercise of their rights as citizens, government expanded, and blacks became an interest group in a coalition supporting expanded government.” 6

The idea that Blacks are now simply a special interest group where before they had legitimate claims is obviously not a value-neutral observation but a slice of Reagan-era ideology. The Toughs have an urgent, explicit agenda. Constitutional law professor Kathleen Sullivan has written that David Brock’s book, The Real Anita Hill, is less a work of investigative journalism than “a tract in a cultural war” against progressive policies.7 In such a context the Tough Love Crowd’s mantra, “unhappy truth,” is a hapless oxymoron.