Читать книгу Clarence Thomas and the Tough Love Crowd - Ronald Suresh Roberts - Страница 24

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Will “One Lave” Work Right Now?

ОглавлениеYale law professor Stephen Carter and Harvard law professor Randall Kennedy, unlike Shelby Steele, do not seek a somehow raceless culture. Unlike Sowell, they do not seek to displace race by a mock-scientific public policy. They generally believe that it is both futile and undesirable to make such attempts. They value what Carter calls racial solidarity. Carter and Kennedy believe, however, that race presents the intellectual with dilemmas. Carter finds aspects of racial identity potentially “inimical to the intellectual life” in which one ought, ideally, to be “a free thinker with ideas of [one’s] own.” Kennedy, too, shares this allegiance. He aims at “a commitment to truth above partisan social allegiances.”

Can such notions conflict with commitments to racial justice? In one sense, Carter and Kennedy fully admit, even insist upon, such a conflict. They assume that sometimes the intellectual’s allegiance to truth must legitimately lead her to voice politically awkward conclusions. However, thus framed, the issue is an easy one. Nobody, intellectual or otherwise, ought generally to tell deliberate lies (but certainly, lie to the KKK about where the fleeing Negroes are, to the German Nazis—past and present—about where the Jews and “Gypsies” are).

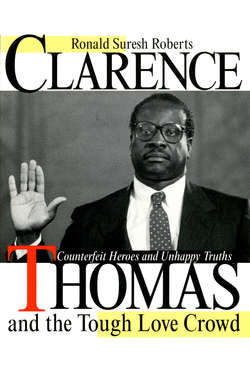

An unthinking refusal to criticize public figures on the sole basis of their race is positively harmful. It is easy to answer the question, Ought Clarence Thomas’s race to exempt him from public criticism by blacks who disagree? Obviously not. Such automatic solidarity worked in favor of Thomas, and against important interests, in Thomas’s confirmation hearings. Unthinking solidarity is hardly an ideal. The interesting debate is not over whether to disclose or to conceal criticisms of prominent African Americans.

We are on more interesting ground when Carter objects to the “ridiculous proposition that Clarence Thomas ought to have certain views.” Contrary to Carter’s unargued suggestion, everyone is surely equally entitled to have an opinion about what views Supreme Court justices ought to have on any issue of concern. And if lots of us dislike lots of Thomas’s views, it is sensible, not ridiculous, to oppose him. Carter’s view that blacks seeking public office have a “right” might seem dictated by his view that “open dissent is an act of loyalty.” Although Carter states this view of “dissent” as a truism, it surely raises a question. Is dissent always loyalty? Is melanin really a carte blanche? Is Judas defunct in African America?

The debate surrounding Randall Kennedy’s “Racial Critiques” article, in which he attacked Negro Crit writings, offers a good entry into this discussion. Richard Delgado, a Kennedy critic and himself a target of Kennedy’s article, correctly rejected the view that Kennedy ought to withhold the article from publication simply because a group favored nonpublication. However, Delgado declined to join in the view that Kennedy shares common ground with Negro Crits. Delgado insisted that Kennedy and others are doing something very different from Negro Criticism. That suggestion raises the interesting debate about the political consequences of associating oneself with inherited ways of doing things. It allows discussion of whether Julien Benda’s hold on contemporary thinking has political consequences. Perhaps progressives who do things in old ways advance something other than justice? This issue is lucidly defined by Edward Said, near the end of Orientalism: “The trouble sets in when the guild tradition . . . takes over a scholar who is not vigilant, whose individual consciousness as a scholar is not on guard against ‘idees recues’ all too readily handed down in the profession.”

Carter objects that those who label him a “BLACK NEOCONSERVATIVE” (his capitalization) enforce a “denial of his right to think.” Overab-sorption in labels is certainly always unhelpful, hence my own emphasis on the different views even within the Tough Love Crowd. Nevertheless, Carter’s objection is hard to understand. If some are heatedly resisting Julien Benda while others are shoring him up, we have at least two incompatible projects. Carter’s right to think is not in question; why should anyone’s right to censure be less secure? Randall Kennedy himself, ably debunking the invented specter of “political correctness” on university campuses, has defended every community’s right to “mobilize opinion.” Yet Kennedy, too, laments—when his own ox, the “Racial Critiques” article, stands to be gored—that “disagreement becomes attack and dissent becomes betrayal.”

Kennedy’s complaint here is hard to understand. Kennedy avowedly endorses an ideal of impersonal legal work that is irreconcilable with Negro Criticism. Unless one starts by assuming that legal dispute is a kind of gentleman’s disagreement (what Delgado has called an “elaborate minuet”), it is hard to see how one reaches the conclusion, suggested by some, that respectful disagreement rather than ferocious ideological struggle is the ideal picture of scholarly engagement.

Those, then, are the stakes. On one side are the doubters of the guild, who insist that law schools update their ideals and gear up for justice in the world. On the other are unreconstructed scholars, hewing old wood in Benda’s way. The deficiencies of Benda’s guild are widely conceded. Writing in 1989 (the year that Kennedy’s “Racial Critiques” piece appeared), Andrew Ross could take it as axiomatic that the “claim of disinterested loyalty to a higher, objective code of truth is, of course, the oldest and most expedient disguise for the interests of the powerful.”1 Yet Randall Kennedy endorses just such an ideal in the cause of racial justice. Similarly, Stephen Carter, quoting Kenneth Clark, endorses the view that, in weighty matters, the hordes must be kept at bay: “‘Literalistic egalitarianism, appropriate and relevant to problems of political and social life, cannot be permitted to invade and dominate the crucial areas of the intellect, aesthetics, and ethics.’”

Carter never pauses to consider whether social equality and elitist knowledge production might conflict. He entirely ignores what is arguably the single most influential strand of contemporary thought: the insistence that knowledge and power are inseparable. When Carter says that “a commitment to an inclusionary politics bears no necessary relation to a judgment about what is good and right and what is bad and wrong,” he seems unaware that this is a tendentious and arguably absurd statement. Certainly, Carter is at best raising a question (is an inclusionary politics compatible with entrenched intellectual tastes?) rather than announcing a truth. To detect such issues, Carter need go no further than the epigraph of Michel Foucault’s Language, Counter-Memory, Practice:

Thought is no longer theoretical. As soon as it functions it offends or reconciles, attracts or repels, breaks, dissociates, unites or reunites; it cannot help but liberate and enslave. Even before prescribing, suggesting a future, saying what must be done, even before exhorting or merely sounding an alarm, thought, at the level of its existence, in its very dawning, is itself an action—a perilous act.

When Carter calls for calm voices and common cause he is unaware (or pretends to be unaware) that to heed his call is to hand him victory. It is Carter who is uninterested in questions about the inherited mode of legal scholarship; it is critical race theorists who want to raise those questions. In one of the more significant of his law review articles, “The Right Questions in the Creation of Constitutional Meaning,” Carter notes, with real or feigned perplexity, that “critical analysis without an accompanying denunciation is an art form that barely has a place any longer in legal scholarship.” Carter objects to what he sees as an unfortunate tendency for constitutional theorists to castigate each other for addressing wrong questions. Carter argues that every question is in some sense a “right question,” including the old questions that traditional lawyers have always asked. Carter here enters the tedious rhetoric of pluralism, which has reduced much of American critical practice to the exact opposite of a critical practice and has made so many American intellectuals unthreatening embellishers of the existing order. Carter’s entire constitutional theory proceeds on the frank and debatable assumption that things will always “muddle on” pretty much as they are. Carter’s call for the compatibility of everything, his call for common cause despite his own complacencies, is quietly oppressive.2