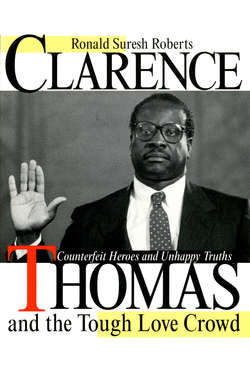

Читать книгу Clarence Thomas and the Tough Love Crowd - Ronald Suresh Roberts - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Preface: The Tough Love Crowd: Disciplined Heroes

ОглавлениеLuckily, we have a fighting tradition. . . . The chain will never be accepted as a natural garment.

—Alice Walker

“The multiple cleavages within racial minority groups undermine the notion of a singular, subordinated racial minority interest.” This comment appeared in 1993 in the Harvard Law Review, and black neoconservatism is widely taken as evidence of its truth. A number of African American professionals have made black neoconservatism seem more a movement than an eccentricity. Yet while there have been suggestions that upwardly mobile blacks will comfortably adopt the politics and outlook of middle America, others have emphasized the enduring rage of African America’s privileged class. Is this rage a problem that ought to be contained or a valuable political resource? Is it dysfunctional or rational? Does it reflect truth or delusion?

The performance of Justice Clarence Thomas on the Supreme Court has given such questions a renewed urgency. The Thomas appointment has given black neoconservatives their first conspicuous political power. The group’s defining trait is Tough Love. They dish out harsh truths for other people’s good. They would elevate the familiar wisdom, “spare the rod and spoil the child,” to the policymaking arena. But does this homespun wisdom serve well in the charged setting of contemporary politics? Answering this question requires a close look at the work of several prominent Toughs.

Thomas Sowell (see chapter 4, “Tough Love Economist”) is a central figure in any discussion of black neoconservatism. He is a senior fellow at the Hoover Institution on War, Revolution, and Peace. A frequent columnist, he has taught at universities around the world. In 1983, the New Republic commented that Sowell was “having a greater influence on the discussion of matters of race and ethnicity than any other writer of the past ten years.” Shelby Steele (with Stanley Crouch, one of the “Tough Love Literati” discussed in chapter 3) is an essayist and a professor of English at San Jose State University. He is best known for The Content of Our Character, published in 1990. Stanley Crouch is a freelance writer and former jazz critic for the Village Voice. A collection of Crouch’s work was published in 1990 as Notes of a Hanging Judge. Stephen Carter (with Randall Kennedy, one of the “Tough Love Lawyers” described in chapter 5) is a professor at Yale Law School. He has written extensively on constitutional law, intellectual property, and other legal issues, and he first attracted widespread attention with the 1991 publication of Reflections of an Affirmative Action Baby. On the appearance of Carter’s second book, The Culture of Disbelief, President Clinton publicly suggested that everyone concerned with the place of religion in American politics ought to read it. (Carter’s subsequent Confirmation Mess, examining the Senate’s role in confirming presidential nominees, was also widely noticed.) Randall Kennedy is a professor at Harvard Law School and editor of Reconstruction, a journal on African American politics, society, and culture. He has written widely on American race relations law and issues of American legal history. His 1989 article, “Racial Critiques of Legal Acade-mia,” attracted much attention for its criticisms of “critical race theory,” a school of thought with which Lani Guinier and Derrick Bell are associated. Vidia Naipaul (see part 5, “Tough Love International”) was born in the Caribbean and has written both fiction and nonfiction concerning India, the West Indies, the Middle East, Africa, Britain, and the United States, among other places. Naipaul has won numerous British literary awards, and the British press routinely calls him the country’s greatest living writer. In 1990, Naipaul was knighted by the queen of England. With the publication of his latest book, A Way in the World, Sir Vidia continues to be revered by many of his British readers, and reviled by many of the postcolonial people he calls barbarians.

Without exception, these individuals present themselves as harsh truth tellers, motivated by concern for those they criticize. They urge that various orthodoxies are blind to harsh facts and therefore unable to offer meaningful solutions. A blurb on the back of Thomas Sowell’s book, The Economics and Politics of Race (1983), assures the hesitating book purchaser that “Sowell has become one of the most ruthlessly honest social critics of our time. He may eventually be recognized as a partisan of the poor because his willingness to face bitter facts can contribute to our ability to help the poor in fundamental and lasting ways” (emphasis added).

All the Toughs make claims like this. Even Naipaul, the Tough Love Crowd’s fiction writer, is often called a remarkable teller of social truth, and he has written more nonfiction than novels. Naipaul declared in a 1993 interview in the London Independent that “several generations of free milk and orange juice have led to an army of thugs.... They seem to think we should do something for them.... I think people should earn their own regard.”

Yet the Toughs attempt such diagnoses in a precarious setting. Parodying a Clarence Thomas favorite, Winston Churchill, one might put the point like this: never in the history of human communication have so many depended so much on so few. In this setting, where news organizations and political handlers manufacture truth, the Toughs get a free ride. Critics say they deliberately betray the groups they claim to champion. They reply, offended, that their good faith is unquestionable. Justice Thomas, since joining the Court, has continued to complain about the pressures imposed by a hypercritical “new orthodoxy.” He has complained that “where blacks were once intimidated from crossing racial boundaries, we now fear crossing ideological boundaries” (Thomas’s emphasis). The usually incisive Henry Louis Gates, Jr., has occasionally been overtaken by such rhetoric, as when he wrote—on the New York Times op-ed page—of the hazards posed by African American “thought police.” Others, too, sometimes find the betrayal claim unfair to the Tough Love Crowd. Even when such persons disagree with the Tough Love Crowd’s agenda, they praise the Crowd’s courage in standing up to the unjustified abuse and vilification of civil rights traditionalists. Such praise is encouraged by the Tough Love Crowd’s own rhetoric. “Dissent bore a price—one I gladly paid,” announced Clarence Thomas while head of the EEOC. With such rhetoric, the Toughs pass as martyrs even as they burnish sacred cows.