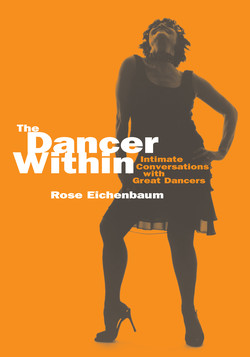

Читать книгу The Dancer Within - Rose Eichenbaum - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеFernando Bujones

I arrived the day before the premiere of the Orlando Ballet’s 30th year gala at the Carr Performing Arts Center. Entering through the stage door, I encountered a bustle of activity: stagehands building sets, props being sorted, dancers stretching and rehearsing.

“Do you know where I can find Fernando?” I asked a long-legged ballerina.

“He’s on the stage,” she said pointing. Spotting Fernando working with a group of dancers, I waited in the wings so as not to disturb the rehearsal. After he dismissed the dancers, I stepped out into the light.

“Hello, Fernando.”

“Rose,” he said with delight, wrapping his arms around me.

“This is some company you have here.”

“Well, just wait until you see them dance! Come, let’s talk in my dressing room,” he said leading me backstage.

“I have a very unusual story, Rose. When I was five years old, I was very thin and didn’t have a good appetite. My mother became alarmed and took me to see a psychiatrist. After examining me, he told her there was nothing physically wrong with me and that my not eating was a ploy to get attention. He prescribed exercise, which he said would boost my appetite and solve the problem. So my mother put me in ballet classes. By the end of the first day, I was starving. My appetite improved and, without knowing it, she started me on my career path.”

“I understand you received your early training in Cuba.”

“Yes, that’s correct, at the Ballet Nacional de Cuba in Havana, with Alicia Alonzo. But I was born in Miami, Florida, on March 9th in 1955. I’m proud of that date because I’m born around the same time as two legendary dancers, Vaslav Nijinsky, born on March 12th and Rudolf Nureyev, born on March 17th. My family moved to Cuba when I was very young, which is where I received my ballet foundation. My professional training began when I received a scholarship to study at the School of American Ballet. This came about when my mother had the opportunity to meet New York City Ballet dancer Jacques d’Amboise. She told him about me, and he offered to watch me dance. Afterwards, he turned to her and said, ‘I will personally see to it that Fernando receives a scholarship for the summer program at the School of American Ballet in New York City. When Diana Adams, one of the company’s principal dancers saw me in class, she began a campaign to keep me in New York. I was offered a full-year scholarship. ‘We are a very close Latin family,’ my mother protested. ‘I can’t possibly leave my twelve-year-old son alone here in New York City.’ A good negotiator, my mother worked it out so that SAB would relocate her to New York and give her a living allowance. I would be enrolled in the professional students’ school for my general studies and SAB would pay the tuition. We returned to Miami, packed our things into a little Volkswagen, and followed I-95 north to New York. This was the beginning.”

“I imagine the teachers at SAB immediately began grooming you for a place in the New York City Ballet.”

“Yes, I received a good deal of attention. They were so impressed with me that my scholarship was extended year after year for the next five years. Mr. Balanchine asked me to join New York City Ballet when I was only fourteen, but I felt that I was too young and not ready. He invited me again when I was seventeen, after my graduation performance. But Lucia Chase, artistic director of American Ballet Theatre, along with Erik Bruhn, one of ballet’s most prominent male dancers, had seen me perform in SAB’s school productions and wanted me for ABT. Lucia Chase told me, ‘I’ve seen you dance and I know your talent. Then she offered me a corps de ballet contract—no audition required. I was faced with a big decision—New York City Ballet or American Ballet Theatre.”

“How did you decide?”

“Well, I had an experience when I was around fifteen that helped me make up my mind. I was in class at SAB when the studio door opened and a head peeked in—a man with a very strong face and high cheekbones. He entered and took a place at the barre right in front of me. And from the minute he arrived, he didn’t take his eyes off of me. His gaze was so intense I felt as if he were seeing right through me. Before class was over he pulled my teacher aside and spoke to him quietly. After class my teacher approached and said, ‘Fernando, Rudolf Nureyev is very impressed with you. He called you a first-class dancer.’ Can you imagine what that meant to me? I was flying high. I left the studio to get a sip of water in the hallway fountain, when I heard the door of the men’s dressing room open and the sound of boots coming towards me. I looked up, and there standing over me was Nureyev. He clicked his heels together and said, ‘It was a pleasure to watch you dance.’ I practically choked on the water. He extended his hand to me and said, ‘I wish you all the best and I hope you make the right decision about what company you choose for your future.’ I knew instantly what he meant. He was saying that with my classical training, I should be dancing classical ballets and full-length story ballets. New York City Ballet’s repertory was based on Balanchine’s neoclassic pure dance ballets—short ballets intended to highlight the physical body, not character or story.”

“Did you feel that if you remained with New York City Ballet you would not fulfill your potential as a dancer?”

“I felt that I would not become the complete artist that I hoped to be. I would be an instrument for a wonderful choreographer, yes, but as dancer, I would be limited. A dance career is not complete unless you grow technically and artistically. To grow you must be challenged. I wanted to be challenged. I wanted to interpret characters and express myself through dramatic roles. And remember, Balanchine always said, “Ballet is woman.” What of the male dancer? I felt there had to be more than performing pirouettes and functioning as a support for the ballerina. I took very seriously Nureyev’s words and kept them in mind when I made my decision. Later in my career I would work with him on several of his European productions. Over the years, he would teach me a great deal and became one of the primary influences in my career.”

“Are you saying that the artist should always do what’s in his own best interest?”

“Yes, absolutely. I think we are entitled to do what we need to do to develop as artists. This is not a selfish thing. We work so hard, year in and year out, staring in the mirror in a narcissistic way to improve ourselves. It’s up to us to make decisions that will further ourselves. As a principal dancer with ABT, I would have the opportunity to interpret roles like Romeo in Romeo and Juliet or Billy in Billy The Kid and the princely roles. Ultimately it was because of its repertory that I chose American Ballet Theatre.”

“Fernando, what is the ultimate goal of the dancer?”

“I think most dancers want to be recognized internationally and perform on the great stages of the world in front of enthusiastic audiences. I had a very successful career with my home-base company ABT, and I also developed an international career as a guest star with most of the major companies of the world: the Royal Ballet, Vienna State Opera, the Paris Opéra, Stuttgart Ballet, and La Scala de Milano. I partnered with some of the most wonderful ballerinas in the ballet world, including Dame Margot Fonteyn, Merle Park, Cynthia Gregory, Gelsey Kirkland, Natalia Makarova, and Marianna Tcherkassky. And I had a dream repertory, dancing in some of the greatest ballets ever choreographed, among them La Fille mal gardée, Les Sylphides, Don Quixote, and La Bayadère.”

“Does one need impeccable technique to achieve true greatness as a ballet dancer?”

“One can be a great artist without being a great technician. There have been many famous ballet stars who did not have the ideal body or total mastery of all aspects of the art form, but on the stage they possessed magnetism—true artistry, by which I mean a charismatic quality. You can work with a coach to try and develop it, but a true artist has the ability to express his inner feelings naturally. Some roles bring this out more than others. When I danced the role of Solor in La Bayadère, I was not Fernando Bujones interpreting a role. The minute I put on his turban, I was that Hindu warrior in the palace.”

“How does one make this shift?”

“I don’t think there is a technique for this. It is governed by one’s soul. As soon as I began rehearsing La Bayadère, I felt this character in my skin. The same thing happened when I danced the role of the flamboyant Basilio in Don Quixote. With my Hispanic roots, no one had to say to me, ‘Let me see that Latin fire.’ It was there from day one. I felt it deeply in my soul. And there were other characters, like the Scotsman James in Les Sylphides. James is noble and romantic, a dreamer and a poet. His lyrical nature brought out the softer side in me. Dancing these roles I found within myself the capacity for both fire and poetry. Sometimes I feel so powerful I can break down a wall with my temper, my fire, my strength. At other times I can hand a woman a handkerchief and tenderly caress her. My wife Maria says she fell in love with me because I am half barbarian and half prince,” he added with a burst of laughter.

“You exude a great deal of confidence and self-assurance. I imagine this served you well throughout your career.”

“Some people confuse that confidence and determination with arrogance. I’m not arrogant. I am confident. When I stood on the stage as a dancer, I felt as if I were ten feet tall. How is the audience going to take you seriously if you don’t have a captivating stage presence, one that comes from inside of you?”

“You were criticized in the past for making derogatory remarks about Baryshnikov. What prompted your remarks?”

“I was nineteen when I said in a New York Times interview that ‘Baryshnikov has publicity, but I have talent.’ I had just won the gold medal at the International Ballet Competition in Varna, Bulgaria—the first American male dancer to do so. I was standing up for myself, and for the American dancers. I wasn’t saying that Baryshnikov had no talent. My intention was to point out that the Russian defectors were getting all this publicity, but their talent did not exceed ours in the United States. That statement went around the world like lightning and created a big controversy.”

“Did the two of you become rivals?”

“Yes, Baryshnikov and I had a strong rivalry, like Placido Domingo and Luciano Pavarotti had at one time. After he became artistic director of ABT, many thought I would leave but I stayed for six years. Our backstage rivalry played out on the stage and audiences loved it. It helped sell tickets. We never did become friends. The rivalry always seemed to be in the way.”

“Your dancing career spanned thirty years. It must have been very tough for you to retire.”

“I gave my farewell performance with ABT in 1995 at the Metropolitan Opera House. I was forty years old. It was an emotionally heartbreaking evening for me. I knew that I was closing a chapter of my life and tried to prepare for it. When I made my entrance, the audience burst into applause and bravos for almost a minute and a half. I could hardly hear the music over the din. The evening ended with a twenty-minute standing ovation.”

About a year later, on a hot muggy day in New York City, I met Fernando and his wife, Maria, on the plaza at Lincoln Center, hoping to snap a few photographs of the legendary ballet dancer. Before posing Fernando in front of the Metropolitan Opera House, where for three decades he had mesmerized audiences with his brilliant dancing, Maria patted clear powder on his face to remove any shine that might show up in the photos. He kissed her, stepped out in the sun, and turned on the charm. Wearing a blue shirt, dark suit, and robust smile, he looked majestic before the lens in a pose reminiscent of Don Quixote. I had no idea that this would be the last time he would pose for a portrait. Only a couple of months later, Fernando would be diagnosed with malignant melanoma, which would take his life on November 10, 2005, at the age of fifty. My photograph of him in front of the Met would appear on the opening page of a tribute in the January issue of Dance Magazine, which hailed Fernando as a dancer of spectacular bravura and styling.

Orlando, 2004New York, 2005