Читать книгу The Dancer Within - Rose Eichenbaum - Страница 18

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеDudley Williams

“Now, after forty-one years, your time with the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater has come to an end. What’s it like looking back?”

“Oh, these were the most fabulous years of my life. I only wish that every time I danced Revelations I had put twenty dollars in a savings account. I’d be a wealthy man today. We performed Revelations in almost every program for over forty years and sometimes twice a day. Honestly, I can’t even estimate how many times I danced it. But what a joy it was. What a joy! And the piece is indestructible. I’ve seen so many casts come and go, and it just continues to shine. It’s an absolute masterpiece. In the forty years that I performed it, and I danced almost every single male role, Wading in the Water, Daniel, Cinnaman, you name it, I never, never, never got tired of it. I never once said, ‘Oh God … we have to do Revelations.’ I always looked forward to it and found meaning in it. Alvin gave us what I call ‘jazz soul meat.’ You could dive in whether you were a modern dancer or a jazz dancer. Alvin’s choreography allowed you to completely express yourself. I’ve always been grateful to him for what he gave me and feel really good about the fact that I told him so before he died.”

“What prompted you to confess your appreciation?”

“We were in Los Angeles performing at the Wilshire Theater when for some reason he and I started reminiscing about the past. And then he said all of a sudden, ‘Dudley, I’m going to die, soon.’ ‘Oh, Alvin, we’re all going to die,’ I said jokingly, having no idea that he was delivering me a message. Suddenly, out of the blue, I felt the urge to thank him for everything he had done for me. ‘Alvin,’ I said. ‘I want to thank you from the bottom of my heart for giving me your stage and for the possibility of doing all these wonderful, wonderful ballets.’ It meant a great deal to me that he knew that. He was already sick at the time, but none of us knew it. He died shortly thereafter in 1989.”

“Will you ever stop dancing?”

“No, that would be like cutting off my air supply. I would just fade away and die. I’ve only started to feel this way recently—when I turned sixty-five and started getting Social Security. You see, I have no desire or intention of ever stopping.”

“What is it about dance that has such a hold on you?”

“It’s what I’ve loved all my life, and it’s what I do best. I can’t think of anything I love more than the challenge of getting inside a choreographer’s head and bringing his vision to life and creating a dialogue that can be shared with an audience.”

“How do you bring movement to life?”

“Well, that’s not something I care to reveal.”

“Why not?”

“I don’t want to encourage imitators. I don’t want others to dance like me.”

“Do others try to imitate you?”

“Yes, of course they do. They try, but they can’t.”

“Why can’t they?”

“Because imitators don’t know where my movement comes from. They think it’s muscular action. Yes, I use my muscles, but my movement originates in my heart. I can’t teach others what’s in my heart. My heart speaks through interpretation of a beautiful choreographed moment. I have never tried to imitate anyone else’s dancing. I found my own way of expressing myself, and that’s what I think others should do. Be your own performer.”

“I’ve been told that Alvin always encouraged his dancers to show themselves.”

“Yes, he did. He never liked cookie-cutter dancers. When he opened the door for me to interpret his moves, I jumped right in. For example, when he choreographed Field of Poppies for me, I decided to hold the penché arabesque for as long as I could before moving on to the next part. One day he comes over to me and says, ‘Oh, Dudley, don’t hold that penché in Field of Poppies.’ ‘But Alvin,’ I said, ‘I’ve been doing it like this for ten years.’ ‘I know, I’ve been meaning to tell you,’ he said and walked away. I just had to laugh. He let me get away with that for ten years and then suddenly changed his mind. But Alvin was very sensitive to his dancers. He would ask them if they wanted him to change things based on their individual training. Some had come from studying ballet; others, from Lester Horton. I was schooled in Martha Graham’s technique. Alvin took that into consideration when he choreographed on me. In all my years of dancing, I’ve never worked with another choreographer who so respected the individuality of his dancers.”

“Dudley, how important is technique in achieving artistry?”

“Well, I’m still trying to figure out who I am. Every dancer has days when they don’t feel like dancing, especially after months and months of touring. I remember Alvin used to tell us, ‘If you don’t feel like dancing, then just do the technique. But know that you can’t get away with that all the time.’ And the truth of the matter is that once you’re on the stage and the curtain goes up and you start moving, you realize you can’t just run through the steps. Something happens inside of you. You have to put some emotion into it, and as soon as you do that, you forget that you didn’t feel like dancing. I can’t put into words what takes over. I think part of it is that you don’t want to make a fool of yourself on the stage, so you rise to the occasion. I remember this one time when we were performing one of Talley Beatty’s pieces in Morocco. I was feeling ill, so I just did the steps, didn’t really invest anything of myself, but got through the performance. Afterwards I felt very depressed.”

“I think once you stop getting depressed about things like that—you’ve lost the commitment.”

“Yes, I felt bad about that because I didn’t put any heart and soul into it. The other side of that is that after forty years of dancing on the stage, I have yet to do a perfect performance. I’ve never walked off the stage and said, ‘that was it.’ There was always something in every piece that went wrong for me. But even when I gave an excellent performance and wanted to repeat it the next night, I couldn’t. I’d try to do all the same things. I’d eat the same food, go to the bathroom at the same time, do all sorts of crazy things, but as soon as the curtain went up—I’d realize I’m a different person today than I was yesterday. There is no way to duplicate a performance.”

“Do you think maybe you’re too hard on yourself?”

“If I’m not hard on myself, who will be? I’ve never thought of myself as a great dancer. I’m an okay dancer. I am an okay dancer. I’ve been at it for forty years, but I’ve never, ever, ever, thought of myself as one of the greats.”

“Do you think you’ll ever achieve perfection?”

“I certainly hope so,” he said with a smile. “I think it’s that yearning for perfection that keeps me going. And I intend to go all the way until I can’t lift a leg or move a muscle. I still want to work with choreographers who give me material I can sink my teeth into. I want to be part of a creative journey. Right now I’m working with Gus Solomons, Jr., and Carmen de Lavallade in a group we formed called Paradigm. The choreography is geared toward the mature dancer and wonderfully challenging.”

“I imagine it takes years to understand how to translate what you learn in the studio and give it performance value.”

“Well, I think I was pretty lucky having learned how to perform from Martha Graham and her disciples: Yuriko, Mary Hinkson, Ethel Winter, Helen McGhee, and Bertram Ross. Martha Graham picked me to perform in her company after I graduated from Juilliard in 1959. She was smart as a whip—and, oh, the drama,” he said, demonstrating a contraction with his arms turning in over his head. “She had already retired from the stage when I entered the company, but she was still teaching, so I got much of it straight from the horse’s mouth. She taught her dancers about imagery—to feel what you’re doing. I felt so inspired during class that I made a practice of positioning myself under the studio’s recessed lighting. It made me feel as if I were on the stage—under a spotlight. By the time I got to rehearsals I was working at a performance level.”

“How did ‘A Song for You’ become your signature piece? The song’s lyrics could be your autobiography.”

“I’ve been performing that dance since 1972. ‘I’ve been so many places in my life and times…. With ten thousand people watching….’ I discovered this record, A Song for You by Donny Hathaway, when I was in Canada. When I got back to New York, I gave Alvin the record and said, ‘This music, it’s absolutely fabulous.’ I then left on tour, and when I got back, Alvin called me into one of the studios. ‘Chicken,’ he said. He liked to call me Chicken because I was so skinny. ‘I have a surprise for you.’ He put on the record and said, ‘I’m going to do this for you.’ I was truly overwhelmed, you know, started crying and carrying on. He choreographed the dance on me in three days and then encouraged me to make it my own.”

“How did you feel the first time you performed it?”

“The movement, the lyrics, it was so powerful. But it took some time for me to really dig into it and realize what it meant to me. Gradually I began to play with it on the stage: I’d do two turns instead of one, go deeper into the contraction, extend the amount of time I held my arms in the air, accentuate the use of my hands and fingers.”

“As part of the company’s repertory, you eventually had to relinquish this work to other dancers. Was it difficult for you to pass it on?”

“Yes, very. I passed it on begrudgingly. I knew I couldn’t hog it up, be a pig about it. I taught it to several of the younger male dancers: Matthew Rushing, Amos Mechanic, and others. But I only taught them the steps. I didn’t reveal its essence as I understood it. I let them work it out for themselves. I refuse to show others how to become artists. Besides, it’s not something you can teach.”

“Dudley, what does it feel like for you when you’re on the stage?”

“Honestly, it’s a very nerve-wracking experience. Before a performance I pray that the theater will burn down. It doesn’t matter what piece I’m dancing—I’m terrified. For me it’s like going before a firing squad. A week before I have to perform, I start sweating, stop eating, and stop sleeping. I think that’s why I’m so skinny. The energy I use worrying about performances simply devours me. I have something coming up next Thursday and I’m already sweating. And this is a piece I’ve been dancing for five years. I shouldn’t be nervous. But I am.”

“So if it’s so tormenting, why do it?”

“Why do it? Because I love it, and I want the love of everyone in the audience. I want to hear those bravos and see those standing ovations. When I meet a stranger on the bus who says to me, ‘I saw your performance the other day and you were magnificent,’ I’m in heaven. But I never let on that it means so much to me. I say ‘Thank you’ and act a little humble, but inside I’m shouting ‘Yes! Yes! Yes!’ That’s what I do it for, Rose. I can tell you it’s definitely not the money!”

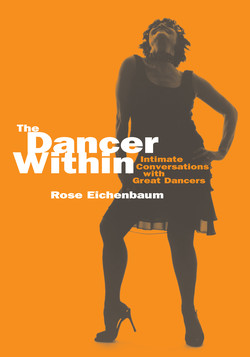

About a year later Dudley and I met again for our photo session.

“I brought some music like you suggested,” he said, and handed me a stack of CDs. On top was A Donny Hathaway Collection. I placed the disc in the CD player as Dudley stepped onto the seamless and began to stretch.

“You ready?” I asked.

“Go ahead.”

I walked over to the CD player and pressed play. A chill ran up my spine when I recognized the piano intro to “A Song For You”—Dudley’s signature work. Within seconds Hathaway’s clear soulful voice filled the studio. Dudley heard his cue in the music, hinged back, and began to carve the space with his long thin arms as he’d done hundreds of times before in concert halls around the world. But on this day, he performed it solely for me. I got down on my knees and began shooting. I tried to catch every move, every gesture and nuance. His eloquent dance left me trembling. After the shoot, Dudley walked up to me, holding the Donny Hathaway CD.

“Rose,” he said, “I watched you during the session and could see how this song feeds your soul. I’d like you to have it,” and he handed me the disc.

New York 2004, 2005