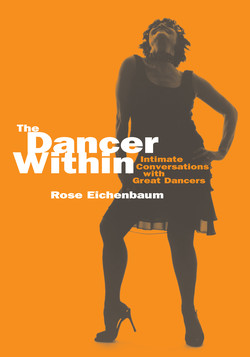

Читать книгу The Dancer Within - Rose Eichenbaum - Страница 17

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеJacques d’Amboise

Jacques greeted me at the offices of his Manhattan-based National Dance Institute. After showing me around and introducing me to his staff, he donned his backpack and said, “Let’s grab some lunch.”

“You have an amazing operation,” I said as we walked to a nearby deli. “You’re really making a difference in the lives of young kids.”

“My goal,” he said, “is to bring dance to children all over the world, rich and poor—from the highest to the lowest points on earth—Mount Everest to the Dead Sea.”

“That’s ambitious.”

“Yes, it is, but we are doing it. In fact, I only have about an hour for our meeting today. I leave for China at the end of the week with a group of kids. There are still a million details to be worked out.”

“What exactly do you need from me,” he asked, taking a seat and handing me a menu.

“I’d like to get your take on what it’s like to have a career in dance and live the artist’s life. You’ve been doing this since you’re what—seven years old?” Before he could answer, a pretty young waitress appeared and asked, “Vhat can I get you?”

“Govoryte po-russki? [Do you speak Russian?]” Jacques asked her.

“I’m from Bulgaria,” she replied.

“Ah … let me see, I think Bulgarian is very similar to Russian, yes?”

“Yes, very close,” she said. Relishing the opportunity to practice his Russian, Jacques learned within minutes that the name of our waitress was Sophia and that she’d soon be returning to her native land to finish her university studies.

Jacques nodded his approval and gave Sophia his order in his heavy New York accent.

“Yes, I did start ballet at seven,” he said, picking up where we’d had left off. “I attended the School of American Ballet at eight. George Balanchine cast me as Puck in A Midsummer Night’s Dream before I was nine, and from then on I performed many of the children’s roles in Ballet Society, which was the company that preceded New York City Ballet. When Balanchine invited me to join the company, I quit school. That was in the summer of 1949. I was fifteen years old. He gave me a flexible contract, so I had the freedom to do a variety of things. I went to Hollywood at the age of seventeen to dance in the film Seven Brides For Seven Brothers. I turned eighteen on the set. I became a principal with New York City Ballet before I was nineteen and stayed with Balanchine until he died in 1983.”

“Did you aspire to be the greatest dancer of all time?”

“Honestly, all I ever wanted to do was play,” he said. “I stumbled into the art of play on the highest level—storytelling to music with the physical body in the context of theater. That’s dance.”

“So games like baseball didn’t hold the same interest?”

“Well, picture this,” he said setting his sandwich on his plate. “George Balanchine, Frederick Ashton, Jerome Robbins, and Antony Tudor setting work on me, dancing with the greatest ballerinas in the world, Stravinsky conducting, making feature films. Imagine … getting paid for all this. Why would I want to do anything else? And you …?”

“Me?”

“Yes, you. When did you do your first plié?”

“Oh … in high school. I only discovered dance at the age of sixteen—sort of late. One day after nearly fainting from running a mile in a timed sprint in my P.E. class, I decided that I’d had enough of track and field. I stormed into my guidance counselor’s office and demanded to be transferred out of P.E. I didn’t care where they put me—swimming, tennis, archery—as long as I didn’t have to run the track. My counselor suggested dance class. I agreed without any idea of what that really meant. The next day I entered Rose Gold’s modern dance class. And in that very first class, my life changed forever. But this is not about my dance path, Jacques. Tell me more about yours.”

“Well, I just always tried to do my best and live in the moment. I danced every performance as if it were my first—and my last. Even if I had performed the same ballet hundreds of times, I viewed it as if it were my last curtain call. I had this ritual I used to do before every performance. In my mind I would dedicate that evening’s show to someone special in my life. You know, like when someone writes a book or produces a movie, they say, ‘in memory of.’ Sometimes it would be to my dance partner, but more often it was to one of my former teachers. I’d think to myself, ‘you’re going to be proud of me, Mr. so-and-so.’ He might be dead, but I’d imagine him out there watching me. Doing this made my performances more meaningful and more joyful.”

“Did you know early on that your involvement with dance would be for life?”

“I didn’t know that I wanted to dance for the rest of my life until I was about twenty-three. Up until then, I kept thinking I might go back to school, become a doctor or something like that.”

“So what made you decide to stay in dance?”

“Balanchine decided to revive Apollo. He originally choreographed it in 1928 at the age of twenty-four. It is considered among his most masterful works. It brought him international recognition and was the first ballet he choreographed to the music of Stravinsky. Apollo combined a new classicism with a modern age that was reflective of Fokine, Massine, and Nijinsky. He chose me to perform this seminal work—a role of a lifetime! Balanchine envisioned a whole new look for the ballet with new costumes and new scenery. Naturally I agreed to do it. I would perform Apollo probably more times than anyone else over the next twenty years. It was extremely challenging, and I don’t think I ever reached its core, what’s truly inside of it. I don’t think there is a dancer who has.”

“Why? Is this ballet so deep, so complex?”

“Well, you need so many things in order to really bring it to life. You need the physical body, the stature, the classical technique, and the drama. You need a master like Balanchine to teach you and guide you. You need the orchestra and great ballerinas all dancing on the same high technical level.”

“So without Balanchine how is it passed on?”

“Well, it’s not—not in the way that I learned it.”

“Why can’t you pass it on?”

“Well, I tried. I don’t know how well I succeeded. Twenty years after I last performed, Helgi Tomasson asked me to come to San Francisco to coach his dancers. He has a beautiful company, but I wasn’t there every day working with the dancers, coaching them and watching every performance. You have to remember that when I was asked to dance the role of Apollo, I had great resources to draw upon. Balanchine’s pianist was on hand as was Nicholas Magallanes, who had danced the role years before in Ballet Caravan. I was able to look to them for advice. ‘Watch Balanchine and copy him,’ they told me. And so I did. And yet, when people asked, ‘Mr. Balanchine, what’s going to happen to your ballets? What about the company after you’re gone?’ he would say, ‘After me, I don’t care, there will be something else.’ He even refused to name anyone as his successor. He didn’t care about becoming a museum piece. He hated the idea of it. And he was right in his thinking. Times change, people change. It becomes something else.”

“Do you think you had natural talent?”

“No. But I wanted to be perfect. I worked hard to be good and had some tricks up my sleeve. For example, I didn’t have a very good turnout, so I learned how to fake it. I’d show the audience a turned-out front foot and hide my other not-as-turned-out foot directly behind it. I had bad feet, so to give the illusion of high arches I would tape them to make them look better. Another thing I used to do was keep shoe polish in the wings, so if I scuffed my shoes I could immediately clean them to make them look neat before going on again. I always felt that every new performance was another opportunity to do things better. Last night’s performance is gone, it’s over, and the only thing that matters is what happens tonight. Tonight I’m a new person, and this may be the only chance I ever have to give my best performance. This performance has to be it.”

“Did you ever worry about forgetting the choreography or messing up in front of thousands of people?”

“No, I never worried about that because I had a system to reinforce the choreography so that I knew it instinctively. Before a performance, I’d get to the theater before anyone else arrived and I’d sit in the house facing the stage. I would think, okay, we’re doing Raymonda, the first variation. I would watch myself in my mind’s eye doing an entrance and my first steps.”

“In other words, you did visualizations?”

“Yes. And then I would go to the rehearsal room, and I’d take that first entrance and go over and over it. I would do it fast and I would do it slow. Sometimes I would do it with my eyes closed. Then I would make myself do it three times in a row so that it was definitely part of me. I’d do the same thing with the first step. Then I would repeat the entire exercise with the second step, and then the third, and so on. It might take me two hours to make it halfway through a variation, sometimes four hours before I owned it. Then, when I came on the stage, I had no fear because I had complete control of the choreography and no tempo change could throw me off. All I needed to do was dance to the music and enjoy myself.”

“It’s about having control and confidence.”

“That’s right. I always tell the children I teach, ‘When you learn how to control how you move, you’re taking steps to control how you live. It’s the right foot not the left. It’s lifted halfway, not all the way. Does it move fast or slow? And what do you want to convey with that gesture or movement?’ It’s so profound. They are learning how to control the time and the space they inhabit. And the way one moves in time and space defines the life of the dancer.”

“It’s no wonder you are so successful working with children. You have a deep understanding of what they need to go through. Yours is a noble mission.”

“Rose, it’s not really a mission. I simply realized what a transforming experience being an artist is. I wanted to share it. There is great joy in being consumed with an art form and making it your life. And it’s true of all the arts, whether it’s learning to play a musical instrument, drawing or painting, writing, singing or acting. If you are lucky enough to ‘play’ with tremendously talented people as your teachers, it is a soul-transforming epiphany. At National Dance Institute we take the best professional artists we can find who are interested in conveying to children the joy of dancing. In New York City we teach dance to two thousand children a day.”

“They embrace dance willingly?”

“Yes. Nothing engages you like dance because it includes all the arts. You’re dancing to music. Music and dance are naturally wedded. Costumes, scenery, and lighting are created by visual artists—so there’s your art. Whether it’s an abstract dance or one with a story, you are conveying something. There’s drama involved. And then there is what I call architecture. By architecture I don’t mean in the sense of designing a building, but how you put things together and the order that you put them in. You’ll do the same when you listen to the tape of this interview. You’ll choose some of the things that I say and leave out other things based on what you think is relevant. Right?”

“Yes, absolutely.”

“I call this architecture. So when you introduce dance to children, it’s attractive to them because it encompasses all these things. All you need is a dance space. Dance can be practiced in a hallway, on a rooftop, or in someone’s backyard. The minute you create a dance space it becomes sacred.

“Listen, I’ve got to get going. Why don’t we talk some more when I get back from China? ‘Pozhalysta, [Please],’” he called out to Sophia, “‘I need the check.’ Looks like we won’t have time for that portrait you wanted.”

“Let me just take a few reference photos, if that’s okay,” I said, pulling a loaded camera from my bag. “We can do a formal session another time.” He agreed, so we walked outside. Reminding Jacques to stand up tall and look dancerly, I got off a few shots but felt a little funny about photographing the great Balanchine dancer next to a sign that read LEAN PASTRAMI.

As we approached the institute, Jacques recognized a group of hip-hop dancers standing near the entrance. “Hey, man,” he said, giving them a round of high fives and pats on the back. I thought if I could photograph him with these dancers, I might be able to capture his natural enthusiasm and signature smile. At just the right moment, I called out, “Jacques, look at me.”

New York City, April 2004