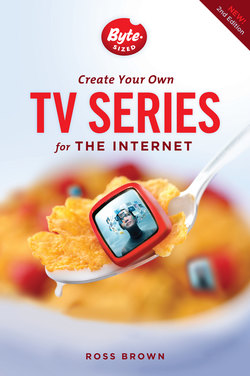

Читать книгу Create Your Own TV Series for the Internet-2nd edition - Ross Brown - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление4 CREATING THE WORLD OF YOUR SERIES

When you create a television series, you are not just coming up with a premise and a bunch of characters to populate that premise. You are creating an entire world, a coherent universe with its own rules, reality, and gravity. That reality can be whatever you want it to be. It can be relatively ordinary, like our own, America in the 21st century. Or it can be something entirely of your own making, an undiscovered planet with its own unique and bizarre reality. This bizarre reality can even be right here, hidden in plain sight in the contemporary United States of America. Take the movie Men in Black, for instance, set in modern-day New York City but with a less than commonly accepted reality to its world, namely that aliens live among us and there is a government agency that patrols and monitors these beings. Or you can speculate what reality might be like in the future, as the digital series H+ does when it posits a future where we all have Internet access implanted directly into our brains. The “reality” and rules of the world you create for your series can be whatever you want. But — and this is a really big but, and I’m talking humongous megabooty — that reality must be consistent and true to itself at all times.

LAYING OUT THE RULES

The rules of your series world can be plain and simple (e.g., it’s ordinary, modern-day New York City exactly as we know it), they can be based on commonly accepted reality (as in Gaytown, where the rules are that gay is the overwhelmingly dominant lifestyle, and the gay powers that be police and punish heterosexual behavior, so straights live closeted and imperiled lives), or they can be a complex set of special rules that define the operation and behavior of a special world, as in the movie The Matrix. But whatever the reality of your series, it must be consistent from episode to episode, and you must clearly define these rules for the audience early on in the series. Think about the movie Men in Black again. In the very first scene, they show you that aliens exist among us on this planet, that there is a special government agency that monitors these creatures, and that the knowledge that aliens live among us is such a closely guarded secret that even law enforcement officials (other than MIB) are kept in the dark. How are they and the rest of the population kept in the dark about this? The filmmakers show you, right in Scene 1. Just after the non-MIB officers witness alien behavior, an MIB agent cleanses their memories with a device called a neurolizer. The major rules of the Men in Black world are all laid out for the audience, right there in Scene 1. A few other particulars are knit in along the way, but the fundamentals are clearly defined up front. This allows the audience to enjoy everything that follows without saying, “Wait a minute, how come there are aliens but nobody knows about them?” If the audience starts asking those kinds of questions or becomes confused by the rules of your world, they are taken out of that world and can no longer enjoy it. Audiences are perfectly willing to suspend disbelief, to follow you into whatever universe you choose to create, no matter how wild and imaginative. In fact, they love it when you take them someplace they’ve never been before; just check out the box office stats for Avatar. But you have to give them a proper sense of gravity in your world by supplying them with a clear understanding of how that world operates.

Another note about rules: Special rules don’t always have to be about aliens or altered states of reality. Your world might be perfectly realistic — say the world of online gamers of The Guild or the world of online therapy of Web Therapy. But these worlds require an explanation of the rules just as much as Men in Black and Gaytown do. Why? Because not everybody knows how online gaming or web-based therapy sessions work. So you have to explain the basics of these worlds to your audience — not by sending them a list of rules or laying them out in a crawl at the top of your pilot but by dramatizing and illustrating how these worlds work right in the body of your story.

So if the characters in The Guild are connected online via their game world and are also connected by telephone and speak to each other over headsets while they interact online simultaneously, you need to show that. Same goes for Web Therapy. The therapist (Fiona Wallace, played by Lisa Kudrow) and her clients are not in the same room. They conduct their sessions via webcam, each in his or her own separate environment. You’ve got to show this early on for the audience to understand and enjoy your universe. This doesn’t mean that you couldn’t ever do an episode of Web Therapy where a client shows up at Fiona’s office or house. It just means that you have to establish what the status quo of this world is on a normal day in order for the audience to understand that in this particular world, showing up to see the therapist face to face is a departure from the norm.

REALITY VS. BELIEVABILITY

Whether it’s a novel, movie, or Internet television series, fiction doesn’t have to be 100% real in a literal sense. Of course, it is made up by definition. But that doesn’t mean that anything goes. Fiction does have to be believable. The audience has to be able to go with the flow of the reality you create. If that flow is interrupted by the audience having a “wait a minute, that’s just not possible” moment, then you’ve lost them. You have violated the unspoken agreement between creator and audience: that they will follow you anywhere as long as the place you take them has a coherent reality to it. This world doesn’t have to be factually authentic; it just has to feel authentic. It has to ring true on an emotional level.

“Wait a minute” moments happen for two basic reasons. Reason One: The fantasy you’ve created is just so far-fetched or implausible that the audience is unable to suspend disbelief and accept your fictional universe. Reason Two: The rules seem inconsistent, or you suddenly or conveniently “forget” about one of the rules you’ve established in order to take the plot a certain way.

Let’s say you wanted to do a satire on presidential politics and our dysfunctional political process. To do this, you create a series where the American public, sick of both the Republicans and the Democrats, rejects both major candidates and overwhelmingly elects a family-sized jar of Claussen dill pickles as president of the United States. You can see the hilarious scenes in your head. CNN reporters on election night show the vote tally with slides of the candidates: Barack Obama 8%, Sarah Palin 5%, the jar of pickles 87%. A record crowd of 4 million gathers near the Capitol steps to watch the historic swearing-in of the brine-soaked veggies as leader of the free world. In the Situation Room, the Joint Chiefs of Staff solemnly ask the Pickle-Jar-in-Chief whether they should invade Pakistan and wait with bated breath as the jar just sits there at the head of the table. All hilarious in your mind. And it might even be worth a 2-minute, one-time sketch on Saturday Night Live or The Daily Show, or it might provide the basis for a very funny YouTube faux news story. But I suspect if you tried this premise as the basis for an ongoing series, the audience would reject it as just flat-out impossible to believe. No matter how dimwitted you feel the American electorate might be, it’s just not believable that they’d actually choose a jar of pickles to lead the free world. And no matter how clueless you feel (fill in the name of the candidate you hate the most) might be, most voters would still choose an actual human being over an inanimate object.