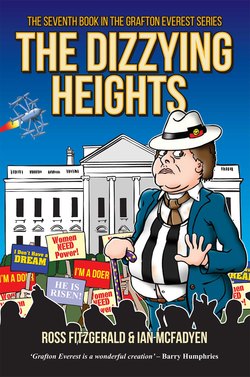

Читать книгу The Dizzying Heights - Ross Fitzgerald - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 2

The Republican form of government is the highest form ofgovernment; but because of this, it requires the highest form ofhuman nature – a type nowhere at present existing.

– Herbert Spencer

‘It’s a complete balls-up,’ ranted Scott Braggadocio.

Grafton was sitting in the living room of Kirribilli, the Prime Minister’s residence in Sydney, drinking tea and wishing there were more interesting biscuits on the plate before him, while the PM strode up and down in a fury.

It turned out there was a slight problem with the republic.

The PM’s Chief of Staff, Angus Morlock, who was sitting opposite him, leant forward and explained the situation quietly as if the room might be bugged.

‘As you know, there were two questions put to the people in the referendum. First whether the President should be elected by the people, or appointed by the government.’

‘As is the current Governor-General,’ remarked Grafton, displaying the kind of knowledge that had made him a professor.

‘Yes,’ said Angus, gliding over the unnecessary observation. ‘The second was whether the President should be an executive President like the US President who appoints the Cabinet and runs the operations of government, or simply a ceremonial figure who formally approves the ministers as chosen by the Prime Minister.

‘Again, as is the current Governor-General,’ Grafton noted.

Angus again accepted the gratuitous note with a nod and continued. ‘That meant there were four options on the ballot paper: an Elected Executive President, an Appointed Executive President, an Elected Ceremonial President and an Appointed Ceremonial President.’

‘Which is what we have now,’ said Grafton.

Angus’s chest heaved in a silent sigh, knowing he should have expected this third unsolicited observation. He went on. ‘As might have been expected, no one voted for an Appointed Executive President –’

‘Because it makes no bloody sense,’ interrupted Braggadocio, who had slumped down in his high-backed Italian leather chair in terse exasperation. Angus paused deferentially for a second and then went on.

‘It was clear that the election of President Thump in the United States turned many people off the idea of an Executive President. So the contest was between an Elected Ceremonial President and an Appointed Ceremonial President. In the end, the Appointed Ceremonial option won by a slim majority.’

He paused, expecting Grafton to chime in with: ‘In other words, what we basically have now,’ but Grafton remained silent. He was just thinking how the result was really a vote for ‘If it ain’t broke don’t fix it’ – which was a major blow to the many people who were intent on fixing things whether they were broken or not.

‘So, what’s the problem?’ asked Grafton, relieved to find that his role was after all just going to be that of a Governor-General under another name.

‘They passed the wrong fucking BILL!’ exclaimed Scott Braggadocio, rising from his chair and hammering the air above his head with closed fists.

Angus waited for the fit to pass and then turned to Grafton and began quietly explaining again: ‘The bill to amend the Constitution was a … substantial document.’

‘Two hundred fucking pages,’ spat Scott, now pouring himself a stiff whisky from a bar concealed behind a fake bookshelf.

‘And because time was of the essence …’ continued Angus.

‘We had to move fast,’ said Scott, coming across and plonking himself down on a chair next to Angus. ‘We didn’t want what happened with Brexit where they had a referendum and then there was all this pressure to have another one because a lot of people didn’t like the result. The Elect-the-President campaigners were already screaming for a recount, saying the referendum was void because the options weren’t clear, blah fucking blah et cetera …’ and he took a substantial swig of single malt.

Angus waited again to make sure that his boss had finished and then resumed. ‘The upshot was that, to save time, the people drafting the Bill, adapted or, shall we say, borrowed …’

‘Cut and pasted is the term!’ interjected the furious PM.

‘Yes, basically cut and pasted large portions of the US Constitution into the Bill. Now I hasten to add –’ said Angus, seeing a look of surprise on Grafton’s face, ‘– they were supposed to remove all references to the Executive Function of the President.’

‘Such as appointing the Cabinet. You know: Head of Treasury, Head of Defence, Head of Education … the whole damn government,’ said Scott bitterly.

‘But somehow, in the rush, that was … overlooked,’ said Angus.

Seeing Grafton’s incredulous look, he added hastily, ‘Or more likely they did remove them but the wrong version was sent to the printers.’

‘And that was the Bill that was passed by the –?’

‘By both Houses,’ said Angus.

‘No one picked up the mistake?’ asked Grafton.

‘Who is going to read a five-kilo slab of legislation?’ railed Scott, holding his hands half a metre apart as if to illustrate the sheer size of the document. ‘It was just supposed to remove any references to the Crown in our laws. Instead, it’s given us a United States-style presidency.’

It was clear why this was a catastrophe for Scott Braggadocio because it meant that potentially he was no longer the head of the government. It was equally troubling to Grafton because being the functioning head of the government of Australia sounded like an awful lot of work.

‘Can’t you just repeal it?’

Angus and Scott writhed in anxiety. ‘Well, the trouble is, that would involve admitting that it happened,’ said Angus grimacing, ‘which could be … embarrassing.’

‘For all parties, presumably,’ said Grafton, ‘given that no one in the House of Representatives or the Senate apparently read the Bill before voting on it.’

‘Yes, it would be a bipartisan embarrassment,’ said Scott. ‘The whole profession of politics is already on the nose with the public – which is one of the reasons they want a goddamn President. Something like this would only make them vote for more bloody Independents. It would be disaster for both sides.’

‘And,’ added Angus, ‘it would certainly lead to a High Court challenge and that would re-ignite the whole debate …’

‘And the Elect-the-President faction would use it to force another referendum,’ added Scott with a sense of finality.

There was a moment of silence when it seemed as if doom was inevitable. Then Angus leant forward with an up-pointed finger. ‘But there is a solution,’ he said, with a look of optimism tinged with a hint of conspiracy. ‘Under the Act, the President can delegate his powers to anyone he chooses.’

‘Meaning,’ said Scott, ‘You can order the Prime Minister to convene the Cabinet and remain the head of the government.’

Grafton felt a surge of relief. ‘Does that mean that I wouldn’t have to actually …’ He hesitated to say ‘do anything’ and settled on just ‘… govern?’

‘That’s right,’ said Scott. ‘We would just go on the way things are with the Prime Minister as the head of the government.’

‘Although,’ said Angus, lowering the skyward pointing finger by several degrees, ‘it would still be wise for you as President to retain some executive function.’

Grafton felt a pang of disappointment. For one shining moment it had seemed the threat of him having to do more than cut the occasional ribbon had been dispelled. Without betraying the qualms that had checked into his stomach, he tactfully asked, ‘Yes, such as … what might that be?’

‘Well … the one thing that all the different factions seem to agree on is that the President has a role beyond that of being a figurehead. Almost everyone feels that the President is in a sense responsible for the general mood of the country.’

Grafton looked over at Scott, who sat sipping his whisky and watching Angus. He was pretty sure the Prime Minister had no interest in this idea at all and would be happy for the President to be kept in a glass case, only to be brought out on special occasions like the best china. Nevertheless, the PM was savvy enough to listen to his policy adviser who was explaining the political advantage of the plan.

‘Everyone knows that politicians have to make hard decisions. Politicians know they will be unpopular much of the time – probably most of the time. The President, on the other hand, is the father or mother of the nation. They are not there to build roads or hospitals or balance budgets. Their job is build confidence, instil pride, create national unity and raise national morale. They are there to promote cooperation, harmony and a sense of togetherness.’

All these concepts were as foreign to Grafton as competing in the pole vault at the Olympics. Good Lord, he thought. This is going to take some doing.

‘So,’ said Angus, building slowly to the pay-off, ‘what I would think is we should formalise that role by creating a special ministry for which you would have sole responsibility.’

‘And what would that be?’ said Grafton, deeply concerned that there might be toil at the end of the answer.

Angus glanced towards the Prime Minister, who took a deep breath and rolled his eyes as if the whole thing made him feel ill. Angus, clearly used to this reaction, turned back to Grafton who was also feeling slightly queasy. ‘It would be something like the Department of Wellbeing,’ he announced.

This wasn’t as bad as Grafton had feared. ‘Well, I was the Professor of Life Skills and Wellbeing at University of Mangoland,’ said Grafton, warming tepidly to the idea.

‘Exactly,’ said Angus, shooting another glance at Scott, who replied with a headshake of disgust.

*

‘So did you ask what the budget allocation would be for this department?’ asked Janet as she packed baking dishes into a carton while Grafton sat at the kitchen bench relating his conversation.

‘Should I have?’

‘I would have.’ Janet had a way of making a comment that seemed to be about herself but was really a comment about him. ‘What about staffing?’

‘Well, I imagine that would be related to the budget,’ said Grafton, only too late realising that this answer could lead to his being forced to admit he had not asked about that either. But then he recalled something. ‘Oh, I do know I get to appoint a head of the department,’ he stated, glad to have ascertained one tiny fact.

‘Who would that be?’ inquired Janet.

Grafton’s demeanour fell as he realised he had not as yet given any thought to this issue nor even realised he ought to.

‘Um … I don’t know. I think there’s still a lot to be … sorted out,’ he muttered.

‘Indeed,’ said Janet, wrapping their plates in butcher’s paper.

Grafton mused on how a single word such as ‘indeed’ could contain so much meaning.

‘Speaking of sorting things out, how are you going with the packing?’ asked Janet, changing subjects as fast as a Formula 1 driver changes gears.

‘I don’t know. It’s a nightmare. I hate moving.’

‘We all do, but we’re going to have to do it, my darling. We have to decide what we’re taking to Yarralumla, what we’re putting into storage and, most importantly, what we’re throwing out.’

‘Well, all my clothes can be thrown out. None of them fit me anymore.’ Grafton went to the fridge and opened it to find there was almost nothing in it.

‘Why is there nothing to eat?’ he asked.

‘Because we have to empty the fridge. No point in buying food when we won’t end up eating it.’

Grafton felt it almost impossible to imagine any food in a house occupied by him not being eaten but he kept this to himself. Instead, he stood staring into the fridge, as he often did, hoping he could perhaps make food appear by a sheer act of will.

‘And remember Lee-Anne’s coming in a couple of days.’

Grafton’s stomach lurched slightly. Janet had reminded him of The Other Thing – the Thing he had been trying to banish from his mind. Lee-Anne, their beloved daughter, their only child, was coming to visit. With her baby. It was not just that the thought of being a grandfather added even more to his sense of being geriatric but that the idea of his loving, gorgeous, creative, politically active and socially aware daughter raising a child was utterly terrifying.

Lee-Anne was a classic upper middle-class only child who had graduated from Disney Princess to dizzy progressive. She had travelled to America to complete a Bachelor of Performance Art (Pole Dancing); had dated the head of an outlaw motorcycle gang; had become an environmental activist; had run a circus featuring disabled women acrobats; and had been married by a celebrant who was a clown subsequently calling for the abolition of films that portrayed clowns as serial killers and calling for people to stop calling clowns ‘clowns’ because it was disparaging. Now married to Wayne Singlet, an Australian-born Silicon Valley entrepreneur, it was this Lee-Anne who was in the position of raising a small child.

Just thinking about it made Grafton feel like he had been stabbed in the liver with an icicle. ‘When is she coming?’ he asked, trying to recall what he had deliberately put out of his mind.

‘The fifteenth,’ replied Janet.

‘What day is it now?’ asked Grafton.

‘The thirteenth,’ sighed Janet. ‘There’s a calendar on the fridge, you know.’

Grafton abandoned his attempt at spontaneous generation and closed the fridge door on which the calendar hung with its small notations pencilled into several days.

‘The problem with calendars,’ he complained, ‘is they only work if you already know what day it is. If you know the date, a calendar will tell you what day of the week. If you know what day of the week it is, the calendar will tell you the date. And it can tell you what you’re doing today and what you’re doing tomorrow … but it can’t tell you anything if you don’t know what day it is today.’

‘Well, today is definitely the thirteenth which means you’d better get a move on.’ Janet sealed a carton with the quick screech of a tape dispenser like a cat going into a shredder.

Grafton sighed and gave up on the Quest for Food. He stomped sulkily down the hall and climbed the stairs – which seemed to get steeper every day – wondering why life had to be so beastly.

‘And I’ve made an appointment at the ophthalmologist,’ called Janet after him.

*

The house in Greenfern was really absurdly big for them but Grafton liked it that way. He liked to know there were places he could hide should visitors ever be rude enough to drop in. Luckily they hardly ever did.

Lee-Anne’s room had been kept just as it was when she left, in case she ever needed to move back home. Grafton had heard, on the few occasions when he had listened to people talk about their children, that it was common now for kids who had left home, having run out of money or split up from their partner, to come back again. While her room remained a museum display of a late twentieth-century girl’s bedroom with Harry Potter books, figurines of elfin princesses leading unicorns and a poster of some scowling, unwashed British rock band, Grafton thought the chances of its former occupant coming back home to live were slim. It was not that Lee-Anne was in any way self-sufficient or independent; it was just that she was married to a Silicon Valley entrepreneur worth at least a couple of billion dollars, so falling behind in the rent was unlikely. And Grafton was sure that if Lee-Anne and Wayne Singlet ever split up, she would be handsomely provided for in the settlement.

‘She’d take him to the cleaners,’ he mused and closed the door.

The room next door was filled with boxes containing ‘The Almost Complete Collection of Grafton’s Life’s Work’. The reason it was an ‘Almost Complete’ collection was not because there was more material elsewhere or because there were still works he was yet to produce. It was because everything in the room was almost complete. There were two novels he had started to write but got stuck halfway and three more where he had written one chapter and then run out of ideas. There were at least a dozen that consisted no more than the title, the dedication and a first chapter heading.

Then there were the plays he had begun and abandoned when he realised he didn’t really know how people talked because he never listened to them. And there were notebooks filled with jottings and ideas, none of which made any sense now. He pulled out a dog-eared exercise book that was filled with random thoughts – apparently the only sort he ever seemed to have. ‘Good enough wouldn’t leave well enough alone. What is that from?’ read one jotting. ‘Donkeys are actually very smart! A film about a clever donkey – donkey that saves the world? Beresford to direct?’ Further down he read: ‘The mating of frogs can last for days!!!’ (the multiple exclamation marks possibly reflecting youthful optimism).

It was highly likely that this practice of jotting down random quotes and thoughts was the genesis of his adult addiction to anecdotes. Janet had often complained how difficult it was to have a conversation with him because he constantly slewed off into irrelevant anecdotes and arcane historical facts.

‘You’re a conversational lucky dip,’ she had once said. ‘A human fortune cookie constantly dispensing gratuitous observational tidbits.’

‘I always thought it was tit-bits’, he had replied, only to have her shake her head in despair.

‘You’ve just done it again!’ she said.

‘I can’t help it. I free associate,’ he said defensively.

‘Yes. Except with people,’ she replied and walked away.

It was true, he reflected. His brain was like the Dead Sea Scrolls, a wealth of historical information existing only in hundreds of tiny fragments. At the same time he believed this was justified. The great theories of history such as Marxism were, in his opinion, delusions. There were no fundamental principles or mechanisms, no underlying forces shaping human destiny, no kind of plan. History was just a succession of random, bizarre events. His own life was proof of that.

This view was immediately supported when he wrenched open another box to find it contained the research materials for his almost-seminal paper ‘The Social Impact of the Great Lisbon Earthquake’ – a perfect example of the unpredictable nature of history. It was also supported by the fact that all the expensively acquired source materials had turned out to be useless because they were in Portuguese, which he did not speak.

The next box turned out to be a collection of bric-a-brac inherited from his mother Avis. He picked up an envelope that contained black-and-white photos of his mother as a young woman, mostly with people he didn’t know. One showed her in a long dress beside his father, who was in evening attire, seemingly at a ball. He recalled that they liked to go dancing. In another, she stood beside a man Grafton did not recognise but who, for some reason, looked familiar. He dropped the envelope back into the box and opened another.

Here he found a collection of old magazines from the mid-fifties called, innocently enough, Photo, but which were clearly not intended exclusively for camera enthusiasts. They were full of black-and-white photos of young women in underwear, posed in what were regarded in those days as seductive positions, smiling sweetly. There were no seductive glowers in those days. Pin-up girls radiated cheerfulness.

He recalled he had found these in the garage when he was about fourteen and never knew where they came from. He wondered if they had been his father’s, although that didn’t seem likely. Despite the forbidden nature of these publications, the tameness of the images was extraordinary. Christ, he thought, this is what we fantasised about in those days? The women were wearing panties and bras, sometimes with the straps seductively undone, or coyly turned away showing a bare back with just the tiniest lunette of clutched side-boob. Still, he recalled, it was a valuable find, for though he spent a considerable amount of time in the newsagent in Hawthorn Road glancing obliquely at the Penthouse and Playboy magazines, he had never had the nerve to actually take one to the counter. Even if he had, he was pretty sure his school uniform would have barred him from buying it.

The next box contained a collection of his childhood books. There were his Just William books about a cheeky and resourceful English schoolboy – a character resembling his own juvenile self not in the least – and comics featuring Rupert Bear, who was a kind of ursine equivalent of William. There was also a faded copy of a Chinese story called The Good Luck Horse about a horse that caused trouble and was called the Bad Luck Horse until he stopped a war and became a Good Luck Horse.

Beneath these, he found a small book of poetry, hand-typed and hand-bound in what was clearly an early attempt at desktop or, more likely, kitchen-table publishing. He opened it and was confronted by a long, ambitious poem about his high school days that was in no small way influenced by Dylan Thomas. It was called ‘Under Forrest Hill.’ He scanned a few lines:

Mr Pellegrino, hair akimbo, tie askew

Ash lapelled, flies cross-buttoned,

Squints through sellotaped spectacles,

Labelling the cilium and the centrosome

With a dwindling nub of chalk,

While outside, beyond the asphalt

A thousand cicadas drag their fingernails

Down the blackboards of the plane trees.

In the hundred-not-out heat

Sweating in a back corner Stiffy Morrison,

Squirming in his too-tight trousers

Draws breasts on his biology book,

And quickly turns them into eyes,

While dreaming of the laminated lamington-laden tuckshop,

Piled with pies, sausage rolls, vanilla slice,

And sucking ichor from a tetrahedral block of ice.

‘Jubbly’ he whispers in a trance, all unaware,

Provoking laughter and the teacher’s stare.

Shit, thought Grafton, and flicked over to find another poem. This was also clearly heavily influenced by a well-known poet and was called ‘The Love Song of J. Alfred Roof-rack.’ He began to read:

Let us go then you and I

Where tiled roofs lie beneath the sky

And smell of sausages and chops

Where the green bus to Moorabbin stops.

And there shall be a time on Sunday morn

To effect the mowing of a lawn

Precisely trimmed around its edge

And then the clipping of the hedge.

For I have seen the Hills hoists and hose’s coil.

I have measured out my life in 2-stroke oil

I should have been a pair of garden shears

Clipping a privet hedge in Georgian years.

At the grocer’s the women come and go

Talking of tea and Iced VoVos.

And somehow there will be a way

To vacuum the venetians in the blue EK.

And do I dare, have I the right

To ask one ‘Is it rubbish night?’

‘Double shit,’ said Grafton out loud. ‘What was I thinking?’ He chanced to take one more look a little further in and struck something that seemed to have been from a Sylvia Plath period.

Death, death, death, death

Death, death, death, death.

The dead dark sun of winter

Sucks life from the leprous lily,

My bones scream. The kiss

Of daylight flays the skin

From my lipless, eyeless face.

My mind is an Auschwitz …

‘Holy fuck!’ he exclaimed. He couldn’t even remember having a Sylvia Plath period and hoped that it was mercifully brief. He looked at the cover of the book and saw that its title was Derivations.

Oh well. Poets never make money anyway. He closed the box.

It was strange, he thought, that the word nostalgia meant a fondness for the past. If so, it could only refer to an imagined past; a past re-edited and re-released as a kind of Director’s Cut of life. His reaction to reading his writings, or hearing audio recordings of himself as a youth, was always one of shock. God, how different he sounded. What a twerp he was. It was disconcerting to realise that if he were to meet his younger self today, he would despise him. Even his physical appearance was annoying – a tall skinny beanpole with shoulder-length hair, grinning out from behind huge glasses, exuding arrogant confidence. Whereof sprang this swagger, this smug certainty?

I remember now, thought Grafton. I thought I was going to be successful.

It was true. He, as a young man, had shown much promise. He had succeeded academically and even showed potential to be a professional cricketer – if he put some effort into actually playing. He had seen himself as starting on a journey that would culminate in fame, wealth and world-wide admiration. A Nobel Prize was not out of the question. Of course, how exactly that fame, wealth and admiration were going to be achieved he had never worked out. He had never made any sort of plan; he had just assumed success would happen of its own accord.

At the same moment he realised the irony of the fact that, in a sense, it had. He was about to become the first President of the Republic of Australia, so why didn’t he feel that his youthful expectations had been fulfilled? Probably, he mused, sitting among his juvenilia, because he had had nothing to do with it. He had been made Premier of Queensland without ever wishing to be; he had been elected to the Senate without even knowing and had been made the Chair of the Eminent Person’s Group (whose apostrophe came before the ‘s’ because he was its only member) without ever seeking to. Now he had been appointed President on the basis of statements that he had never made so, in a sense, his blithe presumption that fame would occur of its own free will had turned out to be true. He was not only a President Presumptive but also a President Presumptuous!

Does it really matter how one succeeds? he wondered as he reclosed and stacked up the cartons. Perhaps famous people only ever succeeded through the efforts of others – standing on the shoulders of giants, as Newton modestly said, perhaps even pushing them down into the mud. But he still had misgivings; he was pretty sure most people who won the Nobel Prize had actually done something, discovered something, written something, invented something that was world-changing. That was it. World changing. You had to do something that changed the world, even slightly. Perhaps that was the Work that he had yet to complete – or even start on.

‘Memories are depressing,’ he said to himself and went downstairs, certain that there had to be some skerrick of food left in the kitchen even if it were just a ten-year-old tin of sardines.