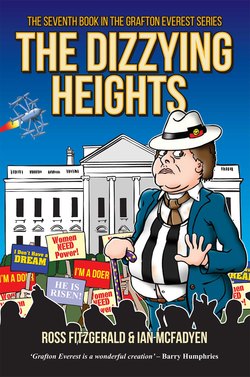

Читать книгу The Dizzying Heights - Ross Fitzgerald - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 1

Old age is the most unexpected of all the things that canhappen to a man.

– Leon Trotsky

Throughout his life, Professor Dr Grafton Everest had been in the habit of regularly examining the part of his anatomy that men of his generation referred to as their cock but which had peregrinated through a succession of names including dick, prick, tool, willy, wang, schlong, dong and old fella, before finally settling into its physiologically correct though unevocative title of ‘penis’. The observance of this ritual, indeed the observation itself, had been, for many years, achievable only with the aid of reflecting surfaces.

Accordingly, Grafton was now standing naked in a sunlit bedroom, amid a sea of strewn and rumpled clothes, peering at himself in a full length mirror, perturbed by the appearance of the organ in question. His concern did not arise from any abnormality in the appendage as such but from the fact that it appeared as nothing more than a small pink blur. This optical effect was not due, it must be stressed, to any kind of propeller-like rotation on the part of his penis but the simple fact that Grafton’s eyesight was now, like the rest of him, appalling.

Grafton was supposed to be going through his wardrobe in preparation for The Move, discarding any pants that could no longer effect the circumnavigation of his waist or were so stained as to be unacceptable even for the op shop. The worthy professor had also throughout his life exercised the practice of turning his pullovers inside-out prior to eating so the inevitable spillage would stain the inside rather than the outside of the garment. This tactic, which he thought was very clever, and had considered trying to patent, succeeded in keeping his knitwear clean on the outside – albeit smelling slightly of soup and gravy – but did nothing to prevent stains in the lap of his trousers, which blemishes were now so numerous and varied as to suggest some form of polychromatic incontinence. After an hour of dragging clothes on and off, Grafton had found nothing that would swathe his lower half except some blue tracksuit pants and he was quite sure that these were not suitable attire for the future President of Australia.

In fact, the surreal reality of the situation was that the Honourable Dr Grafton Everest, Professor Emeritus of Life Skills and Wellbeing at the University of Mangoland (since renamed ‘Excitement University’, now simply ‘Ex-Uni’), former State Premier of Queensland, former independent Senator for Queensland and current Chair of the Eminent Person’s Committee was in the process of moving to Canberra to take up precisely that position.

Grafton’s appointment as the first President of the newly minted Republic of Australia was not only unforeseen but inexplicable to almost everyone, including the half-naked professor himself. However, the event was not as puzzling as it first might seem, if one gave consideration to Australia’s history of managing change.

Among the first pieces of legislation ever to be enacted in the fledgling Australian Parliament was the Law of Unintended Consequences. It was this that led to such ill-considered decisions as each state in the Commonwealth electing an equal number of members to the Senate. This resulted in the island of Tasmania, with a population of around half a million citizens – the size of a provincial city – contributing twelve senators to the Upper House, granting the denizens of the Apple Isle, a disproportionate, and sometimes deranged, influence on the governance of the other twenty-five million Australians.

Similarly, while other nations unlocked vast economic wealth by criss-crossing their lands with railways, Australia had done likewise but with the novel variation of laying the tracks in three different gauges. The result of this initiative was that it was not possible to travel directly from Sydney to Melbourne by train until 1962 – one hundred and three years after the first railway tracks had been laid.

More recently the Federal government had sold off the publicly-owned telephone company just as it was starting to replace its old copper wires with optic fibre. Ten years later the government realised that, as a result, most of the country did not have high speed Internet, so they had to create a new company to complete the fibre roll-out at three times the cost of the original.

In other words, when it came to a major economic or political initiative, Australia could almost always be relied on to cock it up. And so it was with the transition to a republic.

Twenty-five years earlier, one hundred and fifty luminaries – though the way in which they were luminous was never revealed – had gathered in Canberra to discuss the issue. The consensus was that Australia had to sever ties with the British Crown but the effulgent dignitaries were split over whether the new Head of State should be appointed like the current Governor-General or elected like the American President. The subsequent referendum returned a ‘No’ result because the general population disliked both options as well as the people who had drawn them up.

The problem was that many Republicans did not want a Head of State who was just a Governor-General under another name. They wanted a whole new level of government above the Houses of Parliament. Their dream was to have a kind of national ombuds-person who would oversee, and even overrule, the politicians. In this sense they were unwitting monarchists, dreaming of a country ruled by a benign, socially progressive autocrat who, unconstrained by party policies, immune to vested interests, not needing to pander to pressure groups or populist sentiments, or battle rivals in a party hierarchy, would govern purely in the interests of The People. Since the government would never appoint someone likely to veto their decisions, it was essential that that person be elected by The People.

The People, of course, were assumed to be People Like Themselves. The possibility that The People might elect a narcissistic megalomaniac, ultraconservative, impulsive, unstable demagogue was never anticipated.

Until the election of Ronald Thump in the United States.

It was in this political atmosphere that Prime Minister Scott Braggadocio won an election by promising to restart the transition to a republic.

Braggadocio was in fact the sixth PM Australia had had in five years though, to be fair, he had been three of them. Due to an over-reliance on surveys and a total absence of brains and courage, his party had changed leaders five times since Grafton was in the Senate. The Prime Minister at that time, Nina Poundstone, had been toppled in a partyroom coup instigated by Scott who was himself replaced six months later by a stone-faced politician called Mort Thanatos. When polls showed voters would rather emigrate to Somalia than vote for Thanatos, he was replaced by a Christian Outreach moral crusader called Phil Andrews who earned the nickname of ‘Phil Anderer’ when his affair with a Victoria’s Secret model became somewhat less than secret. Scott returned for a third time and won an electoral victory on the promise of another referendum.

His optimism that the time was right arose from the fact that the Queen had finally abdicated in favour of her son Charlie, a blow which changed the attitudes of monarchists considerably. For a while they retained their resolve, certain that the Queen, though in her nineties, would reverse her abdication when she saw the kind of king Charlie would turn out to be. However, she did not change her mind and King Charlie – or ‘KFC’ as he came to be known (the ‘F’ being left up to your imagination) – continued to reign.

In the lead-up to the referendum, the Direct Election lobby campaigned for an elected President by dangling the possibility of a celebrity filling the role. They invited voters to imagine President Blanchett, or President Jackman, President Farnham or even President Barnes. Despite these tantalising prospects, when it came to the day, because of the shock waves still reverberating from the Thump presidency in the US, The People voted by a narrow margin for the Appointment Model. This was a relief to the Parliament but also a concern, for they realised they now bore the onus of selecting a President and would be punished in the polls if they picked the wrong one.

So it was that Grafton Everest, the person calculated by the members of both the House and the Senate to be least likely to impose any kind of ideological agenda, or indeed any agenda at all, found himself appointed to be Australia’s first independent Head of State.

None of which mattered very much to Grafton at the moment. What was troubling him most, as he stood trying to examine his physiognomy, was that he seemed to be going blind.

And deaf.

And losing his memory.

In other words, Grafton had been struck all of a sudden by the awful possibility that he was getting old.

*

Grafton waddled down the stairs in his tracksuit pants, still bare from the waist up, looking like a large Humpty Dumpy egg perched on a too-small blue egg cup, and made his way to the kitchen where he slumped down at the table. His wife Janet was at the bench making a salad.

‘That’s an interesting look,’ she said, glancing at him.

‘I can’t find anything to wear,’ he said sulkily. ‘Everything’s too small.’

‘Or, alternatively, perhaps my darling, you’re too big,’ said Janet. ‘Maybe if you ate more food like this …’

She gestured to the meal she was preparing.

Grafton looked at the salad and winced.

‘I would have to eat a metric tonne of that to fill me up.’

‘Well, have you considered that perhaps it’s the filling up part that’s the problem?’ Janet suggested politely.

‘Anyway, my weight is the least of my problems. My eyes are failing,’ groaned Grafton.

‘Well, that’s all the better reason to go to the optometrist,’ Janet replied.

‘And my hearing is going,’ he added.

‘All the better reason to go to the audiologist.’

‘And I think my memory is going …’

‘All the better …’ Janet began but Grafton cut her off.

‘Will you stop sounding like the wolf in Red Riding Hood,’ he wailed. ‘The point is, I don’t know what’s happening to me.’

‘It’s simple, darling: you’re getting old,’ said Janet calmly, sprinkling some pine nuts and currants onto the bowl of greens as she blithely confirmed his fears. ‘You’ll be sixty-five at Christmas; that’s about the age when things start to break down.’

It had always been one of Janet’s characteristics to show the truth no mercy.

Grafton looked at his wife, who was still tall and slim and very attractive. ‘Why haven’t you aged?’

‘I have, my darling, I assure you. Though I’m flattered that you don’t think so.’

‘But you don’t wear glasses or have a hearing aid …’

‘I do wear glasses. For reading. I wear them every night in bed. Haven’t you noticed?’ asked Janet in surprise.

Grafton frowned. The truth was he had never noticed. Or noticed but not really taken it in. Or taken it in but forgotten he had taken it in. ‘Yes, of course, but you don’t need them for anything else.’

‘I don’t do anything else except for my bird watching,’ she said. ‘And for that, I have binoculars.’

It was indeed the case that failing eyesight had forced Janet to relinquish her former intricate creative activities such as fabric and pencil art and become not only a ‘birder’ but a ‘twitcher’ – one intent on seeing as many new and rare species of birds as possible. As a result, she had been abandoning Grafton for whole weekends to tramp through the Blue Mountains, searching for birds with designations such as ‘ticks’, ‘lifers’ and ‘cripplers’.

To Grafton, these descriptions sounded like people he had worked with at the university.

But all this only strengthened his current case. ‘Yes,’ he said, ‘birdwatching. Hiking through the bush, up hill and down dale, further proof you’re in perfect health.’

‘I wouldn’t say perfect,’ said Janet, opening a small box on the kitchen bench and taking out an assortment of pill containers which she stood in a row. ‘I take this one for cholesterol, this one for reflux, this one for calcium, this one is for iron, this a general vitamin supplement for older women, this is my thyroid supplement, this one for arthritis and this one is a hormone replacement.’

Grafton stared in surprise at the row of containers. ‘I had no idea you took all those.’

‘Well, now you do,’ said Janet, putting the pills back in the little box which Grafton had also never noticed before, probably because his trips to the kitchen always took the form of a beeline to the refrigerator. He was annoyed to discover that Janet took this battery of pills, since he took no medication at all and that seriously undermined his quest for sympathy.

‘Anyway,’ said Janet, returning to her salad making, ‘it’s nothing to worry about. It’s just the normal consequence of aging.’

Grafton continued to slump. ‘What about my memory? I think I’m losing it.’

Janet picked up her salad bowl and headed for the patio. ‘Well, it’s never been good. You’ve never remembered my birthday, or Lee-Anne’s, or our wedding anniversary,’ she said, ‘so I don’t think it’s going to be much of a loss,’ and she was gone, out into the filtered sunshine of the patio.

Grafton sat sulking. It was true that Janet always had to remind him that these anniversaries were coming up but it wasn’t because he didn’t remember the dates; it was because he seldom knew what day it was today.

‘I thought our anniversary was in April,’ he would say.

‘Yes. And we’re in April,’ Janet would reply, and Grafton would be mystified as to how it could be April when it was February just a couple of weeks ago. What had happened to March? How did whole months just disappear?

In any case, he did not forget all anniversaries. There was one which he always remembered and mentally commemorated each year: the date he first slept with Janet. That was a date to remember – the true beginning of the relationship. The subsequent wedding was just a formality. He wondered if women remembered the dates when they slept with people and, if so, did they privately celebrate them. Probably not, he thought. And therein, he mused, lay the intrinsic asymmetry of men and women. For men, that first private, physical communion was the important one while, for women, it was the public, utterly non-physical, one. Weddings were all about dressing up and standing in front of a lot of people – including your parents and even a member of the clergy – and expressing love in words. Sex was all about taking your clothes off and lying down, with no one else around – least of all parents and priests – and expressing love through actions.

Of course, once upon a time, marriage and the first sexual encounter occurred in tandem – a piquant combination of opposites like yin and yang, sweet and sour, Baked Alaska. Since the sexual revolution of the twentieth century, sex had tended to occur well in advance of the nuptials which, while reducing the frustration of courting couples, also removed the pay-off for enduring the embarrassment, discomfort and tedium of the wedding.

Thus pondered Grafton Everest.

He then wondered how he had got onto the topic of sex – to which the answer was simple: sex was never far from Grafton’s mind even if, as though by some divinely imposed restraining order, it maintained a considerable distance from his body. He and Janet did indeed have regular sex but it was according to a timetable not unlike the child access arrangements of divorcees – every-second-weekend. Spontaneous sex was now as much a memory as backpacking across Europe (which Grafton had to admit he had never done) or staying up all night to watch the sunrise (which he also never could actually recall doing, but it seemed a good example).

Alas, he had no time to reminisce about that distant, short, halcyon period when he and Janet seemed to spend more time in bed than out of it. He was due to attend a meeting with his one-time teacher, sometime stepfather and long-time advisor, Mr Lee Horton, about his impending appointment.

‘There’s always something,’ he moaned.

*

Having rummaged through the clothes on his bedroom floor to find the least creased and crumpled garments, Grafton arrived, still looking as if he had slept in his clothes, at a small café overlooking Sydney Harbour. At a far table near the window sat the lean figure of his lifelong mentor. Grafton puffed across the room and sank down in a chair.

‘How are you, my son?’ said Mr Horton.

‘Hungry,’ replied the flustered President Presumptive. He had made a mistake thinking about Baked Alaska earlier and had not been able to get the image out of his head.

‘Have a look at the offerings then,’ said Mr Horton, spinning round the menu which to Grafton’s failing eyes seemed to have been written with pen and ink on wet linen.

As a waiter arrived and sloshed water into glasses then hovered just out of vision, Grafton peered at the text, trying to make out the words, and wondered if he should just heed Janet’s advice and order a salad. He hesitated, however, because most salads these days seemed not to be made from any known plant. Luckily, the waiter cut the Gordian knot of his indecision by reciting the specials.

‘The specials today are sea bass with a thyme and lemon jus and veal parmigiana …’

Grafton immediately surrendered to the parmigiana and handed back the menu.

‘So, how are you?’ asked Mr Horton as the waiter departed.

‘Confused. I mean, I don’t know how this has all happened. How am I … why am I the President Presumptive?’

‘Because you are the best person for the job,’ replied his mentor.

‘Are you telling me,’ said Grafton, ‘that this country is in such bad shape that I am the best person they could find to be the first President of the Republic?’

‘Not you, as such,’ said Horton, ‘but the Grafton that we have created. Who only slightly resembles you.’

‘So who is this public Grafton? I would like to meet him.’

‘He exists only in the digital realm,’ explained Mr Horton. ‘Which is to say, everywhere.’

Seeing Grafton’s look of confusion, Mr Horton leant forward and started to explain, much as he had explained the basic principles of biology when he was Grafton’s science teacher at Forrest Hills High School, many eons ago.

‘My boy, democratic governments lost power the minute the Internet was invented,’ he said. ‘Political power comes from the power to communicate. Once upon a time that meant a wooden soapbox in the park. Then it became radio and television but only major political parties could afford to broadcast on radio and television so they dominated until cheaper avenues arrived. Let me ask you a question.’

Grafton knew this was probably just going end up with him displaying his ignorance but he said, ‘Okay.’

‘What invention enabled the youth revolution of the sixties?’ Mr Horton leant back as the waiter delivered their meals.

Grafton thought about it for a moment and then, not wishing to offer a long list of suggestions, all of which would probably be wrong, just said, ‘What?’

‘The Roneo machine,’ said Mr Horton. ‘The spirit duplicator. It enabled student activists to cheaply run off hundreds of fliers with information about protests and demonstrations, distribute propaganda, announce meetings. They could hand them out on street corners, stick them up on noticeboards and walls. It gave every radical group their own little printing press. The big anti-war demonstrations could not have happened without a Roneo machine or a Fordigraph or a Gestetner. The Internet today is like a Roneo machine on steroids. Everyone is now a broadcaster.’

During this explanation, Grafton was trying to extract his knife and fork from a napkin that appeared to have been wrapped by someone trained in a cigar factory. As he ran a nail around the damask, looking for an edge as one might with a roll of sticky tape, Mr Horton continued.

‘Once, we elected farmers, miners or timber-cutters as leaders. We even had a Prime Minister who was a train driver. But in the modern world, these kinds of people ceased to “resonate”, as they say. The key to political success is “media presence”. ’

‘The Kennedy versus Nixon syndrome,’ added Grafton, finally freeing the cutlery from its bindings and sticking the now permanently curled napkin into his collar – parmigiana sauce being one of the most indelible fabric dyes known to humankind.

‘Exactly, my son. As a result, in America, we’ve seen actors elected to state Governorships and the presidency. Minnesota even elected a wrestler as Governor. And we have had the recent unpleasantness of a TV reality show host becoming POTUS.’

Grafton wasn’t sure what ‘potus’ was but it sounded like a nasty condition and he could think of no one who deserved to suffer from it more than Ronald Thump.

‘Actors and other celebrities are in huge demand to be “ambassadors” for various causes. And why not? Who better to promote awareness of sickness, poverty and disability than people who are healthy, wealthy and physically fit? And it’s a plus for the celebs because they get free publicity for “speaking out” about starvation in Africa or an endangered species without having to actually hand out food from the back of a truck in Somalia or hand-rear a quokka.’

Mr Horton paused to take a sip of wine that was an unusual green colour, and then leant in, as if imparting a confidence.

‘The problem is, of course, that there aren’t enough celebrities to go around,’ he said. ‘It’s almost impossible to find a celebrity who hasn’t already been signed up for some cause or other such as disappearing frogs or fracking.’

Grafton had to admit that he didn’t know there were frogs capable of disappearing. Perhaps, like chameleons, they had the capacity to vanish into the background. Fracking, he presumed, was some form of sexual assault.

‘The solution is,’ continued Mr Horton, building the tension, ‘to create your own celebrity using the Internet. If you can post things that go viral, you will get Followers.’

‘Like Jesus?’ said Grafton.

‘Very much like Jesus,’ agreed Mr Horton. ‘Once you get a critical number of Followers, you become a Presence, a Voice, an Agent of Change, a Political Force. If Jesus had the Internet he wouldn’t have had to go traipsing all round Judea; he could have sat home in Nazareth posting memes from his laptop – “Blessed are the poor in spirit”; “The meek shall inherit the Earth” – and watched them go viral.’

‘So now anyone can be Jesus,’ said Grafton, sipping his mineral water and pondering the implications of this.

‘Yes, providing they can come with some zingers like Jesus did.’

‘Have I come up with any zingers?’

‘Indeed you have,’ replied Mr Horton. ‘And as a result, your digital footprint is the size of King Kong’s.’

‘What have I been I saying?’ Grafton was intrigued to know what his digital doppelganger had been up to.

‘Everything and nothing,’ replied Horton. ‘Your utterances have had the virtue of lacking specificity because the Internet precludes any form of complexity. Ideas have to be reduced to a single phrase.’

‘Like “It’s Time, Stop the Boats, Make America Grate Again”,’ suggested Grafton with a mouthful of veal.

‘Yes.’ Mr Horton interjected quickly to stop the trickle of slogans. ‘Mind you,’ he added, ‘all this only applies to people who get all their information from social media. To the others, you are still the anti-Christ.’

To most people, this codicil would have come as a letdown but Grafton found it strangely comforting. In this mad new world it was a relief to find something that he was used to and seemed normal. One thing, however, remained unclear.

‘But with the new rules, the Australian population doesn’t choose the President,’ he said. ‘They’re chosen from a short list by both Houses of Parliament. How did I win that vote?’

‘Again, easily,’ said Mr Horton. ‘It is essential that the President have no fealty to any particular political party. You have worked for the People’s Party and the Workers’ Party and betrayed both of them, thus showing you can be relied on to have no loyalty to anybody or anything. You are absolutely neutral.’

‘I see,’ said Grafton, intrigued that these days everything that was once considered a fault was now a virtue. ‘So, Mr Horton,’ he began. But Mr Horton cut him off.

‘You know, Grafton, I really think it’s time you called me Lee,’ he said. ‘We’re not in school now. We’re both grown up, and pretty much in the same age bracket.’

Grafton furrowed his brow. How big a bracket was Mr Horton talking about?

Something didn’t ring true even to his egregiously unmathematical mind.

‘When you taught me at Forrest Hills High,’ he said, ‘I was fifteen and you must have been …?’

‘Forty,’ said Mr Horton.

‘That means you were …’ He tried to do the maths but got stuck.

‘I’m twenty-five years older than you,’ said Mr Horton in the same tone he used when leading Grafton through a simple science problem.

‘Which means you’re now …’ Grafton stopped again, not because he couldn’t add twenty-five to his own age of sixty-four, but because the answer did not seem possible.

‘Eighty-nine. In Earth years,’ replied Mr Horton.

Grafton was suddenly treading water in a sea of confusion. Mr Horton looked only a few years older than himself. Then he realised Mr Horton had been looking directly at him throughout the meal, not to mention reading the menu.

‘And I thought you were blind,’ said Grafton trying to clear his mind. ‘Didn’t you have some sort of sonic …’

‘Sonar implants, yes,’ replied the mysteriously non-aging scientist. ‘When I lost my eyesight I had an ultrasonic navigation system implanted – along with a few other things – but then a new technology came along and I had my eyes fixed.’

‘How?’ asked Grafton, both puzzled and slightly unnerved.

‘I’ll explain it all to you at another time.’ Mr Horton glanced up with what Grafton saw were unnaturally clear blue eyes. ‘The main thing now is that you need to meet with the Prime Minister and sort out what your duties are going to be as President.’

‘Duties? No one told me I’d have duties,’ stammered Grafton, suddenly terrified that he might have to do work in this new position.

‘You weren’t supposed to, but there’s been a bit of a mix-up. Nothing serious but the Prime Minister wants to talk to you tomorrow,’ said Mr Horton with an unnerving degree of casualness. ‘Coffee?’

‘Dessert,’ said Grafton decisively and sat back while the waiter cleared the plates – his having been mopped clean right down to the porcelain – and went to fetch the dessert menus. Grafton hated the modern fashion of having a separate dessert menu. His practice had always been to order dessert first, then turn to the front of the menu and consider what kind of main course would lay the appropriate foundation for the chosen sweets.

While he waited, he covertly studied Mr Horton, wondering how his former teacher could look so healthy while he himself was falling apart. He recalled that Mr Horton had once written in a letter, ‘Watch your health. Any neglect now will endure hordes of demons with whips assailing your old age.’ Well, he was certainly feeling the sting of those whips now, but even his egregious neglect could not explain the difference in their appearances. Mr Horton looked younger than any eighty-nine-year-old he had ever seen.

He thought about it but, since not even the most tenuous answer suggested itself, his mind soon gave up and he returned to considering his new and wholly undeserved fame as a font of wisdom and contemporary morality. Je suis Jesus, he thought, and dwelt on the idea for a while not only because it amused him but because, for the time being, it stopped him thinking about The Move and the Other Thing.