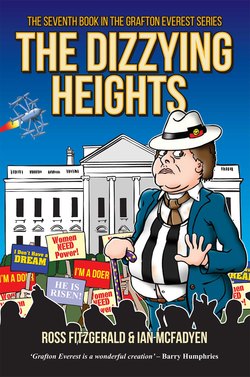

Читать книгу The Dizzying Heights - Ross Fitzgerald - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 3

All we adults have this unspoken agreement that childrenare lunatics.

– Stephen King

The next day, Grafton was sitting with his head clamped into a kind of torture device while an ophthalmologist shone a locomotive headlight into his eyes. The torturer’s face was so close to his that Grafton was sure that he felt the doctor’s nose hairs brush his cheek.

There are some cultures, thought Grafton, where if this doctor were female, we would be forced to get married after contact as intimate as this.

After what seemed like an hour of looking up, down, sideways and around in a circle like an amazed jeweller examining the Cullinan diamond, the doctor leant back.

‘Hmmm,’ he said, which is the last thing a patient ever wants to hear. ‘The problem is not in the lens. There appears to be some bleeding on the retina.’

‘Reeding on the reddina?’ said Grafton, his jaw still clamped shut in the scold’s bridle. ‘Whass at mean?’

‘You can sit up,’ said the doctor. ‘It means just changing your glasses won’t fix it.’

‘So what will?’ asked Grafton, straightening up from the very uncomfortable position.

‘At this stage,’ said the doctor, ‘nothing.’

‘What’s the cause of it?’ Grafton was alarmed as all hypochondriacs are at finding there is actually something wrong with them.

‘It can be caused by high altitudes. You’re not a mountain climber, are you?’ said the ophthalmologist, making Grafton wonder if he was the one who was going blind.

‘No, I’m a devout Lowlander,’ said Grafton. ‘I get dizzy going up an escalator.’

‘Well, it’s probably hypertension.’

‘I do have rather a lot on my plate at the moment,’ said Grafton, wishing that were true in the literal rather than the metaphorical sense.

‘I don’t mean psychological tension. I mean, high blood pressure due to … well, being overweight for a start.’

‘So what can I do?’ said Grafton, now getting seriously worried.

‘Well, the reality is you’re going to have to massively reduce your food intake and you’ll have to start exercising frequently. Otherwise you could lose your vision entirely,’ the medico answered with finality.

*

‘So what did the doctor say?’ asked Janet when Grafton arrived home, depressed.

‘He said I’m going to go blind.’

‘Oh, well.’ Janet was now packing books into cartons in the living room. ‘It’s probably best to take precautions,’ she said.

‘He told me my condition is common among mountain climbers,’ said Grafton. ‘I told him the only heights I had ever scaled were the heights of absurdity.’

‘I’m sure he was concerned,’ said Janet, picking up another flattened carton from a stack and expertly folding it into a box.

‘Gerard Manly Hopkins once said: “The mind has mountains”,’ observed Grafton in his characteristic tangential way.

‘I don’t think mental mountains count.’ Janet was now casting her eye over the increasingly barren room.

‘So what are we doing with all this stuff?’ asked Grafton, worried at seeing all their familiar possessions disappear in a kind of cardboard black hole.

‘Most of it goes into storage, my darling. We can only take personal items.’

This peeved Grafton. He regarded everything as a personal item. He was used to their furniture and drapes, carpets and plates and cutlery. Especially the plates and cutlery, which he regarded as old friends. God knows what strange and alien china they would be eating off in the former Governor-General’s residence. He was repulsed by the idea of sleeping on a bed or eating off plates that had been used by ten former Heads of State. It was going to be like living in the St Vincent de Paul warehouse.

As he silently sulked, Janet continued, ‘I’m only keeping out a few things that Lee-Anne and Wayne might want. They’ll be staying at a hotel for the first few weeks until the Inauguration and then they’ll join us at Yarralumla. They’ve assured me the guest wing will be ready by then.’

‘Who has?’ said Grafton, surprised that Janet had had some contact with someone about the matter.

‘The head housekeeper.’

‘You contacted them?’

‘They contacted me. They wanted to know what our requirements are.’

‘I didn’t even know we had requirements.’ Grafton felt, as usual, that he had missed some meeting in which vital information had been dispensed.

‘Well, you, for example, need a king-size bed,’ said Janet.

‘Do I? I’ve always wanted a king-size bed …’

‘Well, now you’re going to get one.’

‘Wait,’ said Grafton. ‘Do you mean that anything we want they’re going to get for us?’

‘Correct,’ said Janet, responding to his look of childlike wonder by speaking as if to a child. ‘After all, you’re the President.’

Grafton sat down on a stack of cartons, trying to take this in.

‘Sometimes in America,’ Janet continued, ‘the First Lady will redecorate the whole White House.’

Grafton remained silent. His mind was spinning as he realised for the first time what it might actually mean to be the President of Australia. He was not facing the prospect of sleeping in second-hand sheets but possibly the best of everything.

‘You mean …’ he could hardly form sentences, ‘I can have anything I want?’

‘Correct again. Within reason.’

‘And did you say the head housekeeper?’ Grafton asked.

‘Yes,’ replied Janet. ‘There is a head housekeeper, two assistant housekeepers, a butler, four maids, a cook, three kitchen staff, four groundskeepers, a handyman and two drivers. And of course there will be the protective services. Why? Did you think we were moving to a three-bedroom house in Tuggeranong?’

‘No,’ said Grafton, ‘I just didn’t realise it would be so …’

‘Presidential?’ suggested Janet.

‘Yes. I mean, I hadn’t really thought about it but … yes.’

‘That’s why you need to get packing my dear.’

‘Yes. Packing indeed,’ and Grafton headed towards the stairs. He stopped once and turned around. ‘Anything we want, did you say?’

‘Within reason,’ repeated Janet with emphasis.

Grafton mounted the stairs, noting they seemed to be not as steep as usual.

The next day, Lee-Anne arrived.

It was less an arrival than an invasion.

The First Wave was the block-long limo that edged its way down their narrow street, almost taking the side mirrors off the parked cars. The door swung open and Lee-Anne burst out, wearing a lime-green boiler suit and huge sunglasses which gave her a passable resemblance to a mantis. She was followed by her husband Wayne, a short stocky man with orange hair gelled up into spikes. Since he had a bald patch in the middle of his head, it gave the impression he was wearing a paper crown from a Christmas cracker.

Wayne had his phone pressed to his ear and was apparently dealing with some complicated business. As Lee-Anne swung open the iron gate to the Everest townhouse, a third person emerged from the limo, stooped at first but then unfolding into her full height. She was a woman of African appearance – possibly Maasai – dressed in a long gown of brilliant opalescent blues and greens and holding Grafton’s grandson in her arms.

Before Lee-Anne could even knock, Janet opened the door and welcomed her only child with outflung arms as Grafton plodded down the stairs behind, annoyed that he had to put on pants and a shirt. He met Lee-Anne in the hall for a hug and a brief handshake with Wayne, who dropped the phone to his chest briefly for the occasion before resuming the conversation. Grafton then turned to see what seemed like a stilt-walker in a brilliant evening gown.

‘This is our nanny Kiki,’ said Lee-Anne, introducing her.

The nanny stepped forward and handed the baby to Janet, who hugged him to her bosom.

‘Oh he’s gorgeous. He’s grown already!’

Kiki then stepped forward and offered her hand to Grafton. ‘Pleased to meet you,’ she said in a soft African accent.

‘Me too,’ gulped Grafton stupidly, shaking the long fingers awkwardly with his short pudgy ones, thrown slightly by looking upwards at a face higher than his own. Kiki smiled a warm African smile and said, in a voice that sounded like a leopard purring, ‘Lee-Anne has told me so much about you.’

This reduced Grafton to water. He smiled hopelessly and blurted some vowels, none of which were arranged into words, then muttered, ‘You too,’ which made no sense since he had no previous knowledge of this statuesque woman’s existence.

The normal chit-chat about ‘How was your flight?’ was redundant because Lee-Anne and entourage had flown from Los Angeles on Wayne’s private jet. The best Janet could manage was, ‘Do you have any luggage?’ (a hint that Grafton should perhaps go outside and carry in bags).

‘No, it’s already gone to the hotel,’ said Lee-Anne, whipping off the sunglasses and looking around the house.

‘You don’t want to stay here?’ Janet asked.

‘Too many of us,’ said Lee-Anne. ‘But we’ll stay for lunch. I thought you’d like to see Justice.’

Justice, of course, was the baby – Justice Singlet – which Grafton immediately thought sounded like someone wearing ‘just a singlet’. This was not a problem in the US where the Americans called a singlet a ‘vest’, but in Australia, introducing someone as ‘Justice Singlet’ would surely elicit mirth.

‘How was he on the flight?’ asked Janet, gazing at her sleeping grandson.

‘Justice was fine. Justice flies a lot. Justice never seems to mind. Justice sleeps most of the time.’ Lee-Anne’s odd manner of speech arose from the fact that she refused to gender her child by using male or female pronouns. For her, it was up to the individual to decide their own gender when they reached adulthood and she was planning a full-on Gender Party for Justice when Justice reached the age of eighteen. Until the Time of the Gendering, Lee-Anne was resolved to eschew the use of pronouns and, since she disapproved of synthetic pronouns or the confusing ‘they’, she would only use Justice’s name when referring to Justice.

(It was important to note that the gender chosen at the Gendering could be varied at any time throughout a person’s life, though it was not thought that any subsequent regendering warranted a party.)

‘What a good baby,’ said Janet fondly, recalling that Lee-Anne herself cried non-stop for the first year.

‘Yes, Justice is pretty good,’ said Lee-Anne. ‘God, this house is so much smaller than I remembered.’

‘It’s actually too big for us,’ said Janet.

‘And so we’re moving somewhere bigger,’ said Grafton.

‘Yes, congratulations, Daddy,’ said Lee-Anne. ‘Wow! President. That’s awesome. Think of what you’ll be able to do.’

That was exactly what Grafton had been trying to do but so far, nothing was forthcoming.

‘Would you like to hold your grandperson?’ offered Janet, holding Justice out to Grafton.

‘Sure,’ said Grafton, awkwardly taking the swaddled infant into his arms. In his peripheral vision it seemed that Kiki tensed slightly at seeing her precious charge entrusted to an uncertified bearer, but Grafton was comfortable holding babies: he quite liked babies and identified with them, arguably still being one himself. Then the doorbell rang.

‘That’ll be the caterers,’ said Lee-Anne. ‘We knew you’d be packing so I arranged lunch.’

And so the Second Wave arrived: a seemingly endless line of waiters and cooks who poured out of a van like clowns from a clown car. Fitting, thought Grafton, given Lee-Anne’s championship of the clown community.

The family retreated to the patio as the invaders poured down the passageway and into the kitchen where they took charge. Within minutes the table under the pergola was set with fine crockery and glassware, and a trestle table with a full buffet had appeared beneath the purple wisteria racemes. Incredible, thought Grafton watching the chafing dishes being opened by white-clad chefs. Thirty years of parenting has finally paid off.

Over lunch, during which, let it be told, Wayne’s phone never left his ear, they discussed the projects that he and Lee-Anne were involved in. Though the lunch was lavish, Grafton was disappointed to find that it was vegan. Nevertheless, the caterers seemed to have disguised the taste of vegetable matter so well that he actually enjoyed it.

As he devoured small patties of unknown composition, Lee-Anne explained the radical concept that had made Wayne a billionaire: EAI or Ethical AI. Grafton was still in the dark about what AI meant and Lee-Anne had to explain it meant Artificial Intelligence. Grafton nodded. This was not a new concept to him. Having worked in universities for forty years, he had encountered his fair share of artificial intelligence, mostly in people who thought they had the real thing.

‘EAI’, said Lee-Anne, ‘is the use of digital technology and media to promote ethical behaviour in the community.’ Grafton listened closely while helping himself to a celery roulade. ‘The idea was inspired by beeping.’

Wayne lowered his phone for a few seconds; apparently someone or something was momentarily unavailable, so he added, ‘You know how cars beep at you if you haven’t fastened your seat belt or you’ve left your keys in the ignition or your lights are on?’

Grafton knew only too well. It was one of the plagues of the modern world that machines were constantly beeping at you – microwaves, fridges, scanners at shop doorways, washing machines and driers that had finished their cycles. One was constantly being bullied by appliances. ‘These things were supposed to be our servants,’ Grafton complained frequently. ‘How did we get to the point of being bossed around by them?’

Lee-Anne stepped in to continue the tale so Wayne could resume his call. ‘Wayne thought, why should it be limited to just things like seatbelts? Why can’t machines tell us what do in all aspects of our lives?’

Grafton thought there were probably all sorts of reasons but he continued to eat and listen.

‘Let’s suppose you’re an alcoholic,’ said Lee-Anne, making Grafton start slightly. It would have been an insensitive comment had Lee-Anne recalled that her father had been an alcoholic in his teenage years but in her enthusiasm for the tale she hadn’t. ‘Gobble Maps knows where all the liquor stores and pubs are. A car programmed with EAI would simply refuse to drive to a retail outlet that served alcohol. It would reach a certain distance then slow down to a full stop. If the person walked to a liquor store or a bar, their mobile phones or Fatgut watches would start to beep loudly, alerting the staff that they shouldn’t serve them.’

Big Brother eat your heart out, thought Grafton sampling a tofu and beetroot slice that actually tasted delicious.

‘When people entered butcher shops their phones would automatically play a recording of cows being slaughtered or pigs squealing in pain at the abattoirs.’

‘You wouldn’t do something to actually stop them eating meat?’ asked Grafton, surprised at the relative moderation of this initiative.

‘We’re not fascists,’ said Lee-Anne sternly. ‘But people buying meat should at least be aware of the consequences of their actions.’

‘Indeed,’ said Grafton. As far as he was concerned, the consequences or buying meat were a meal of roast lamb or steak and mushrooms. ‘And people are adopting this technology?’

‘It’s going gangbusters in the US,’ responded Wayne, who was clearly capable of talking on the phone and monitoring the conversation around the table at the same time.

‘Yes,’ said Lee-Anne. ‘Employers are buying our anti-harassment software for use in the workplace.’

Grafton looked up. ‘Really?’

‘Since mobile phones can hear everything you say even when you’re not using them, they can detect any sexist or racist language and immediately send a text to the Equal Opportunity Officer,’ Lee-Anne replied. ‘Also, since your phones know your location and other people’s by GPS, anyone standing too close to a colleague will immediately trigger an alarm.’

‘I take it you mean that literally,’ said Grafton, sampling some dairy-free cheese.

‘Oh, yes, it’s a like a police siren,’ said Wayne cheerfully, putting down his phone and turning to Lee-Anne. ‘The Canadians are on board.’

‘Super!’ said Lee-Anne, causing Grafton to stop in mid bite, having never heard Lee-Anne use that particular term before. Lee-Anne then added, ‘Shall I tell Mum and Daddy?’

‘Why not?’ said Wayne magnanimously.

Lee-Anne took a deep breath as if she were about to announce something monumental, which it kind of was. ‘Wayne is about to launch the first space cruise.’

‘How exciting,’ said Janet. ‘You mean, actually taking people into space?’

‘Yes,’ said Wayne. ‘It’s going to be the biggest industry this century, space tourism.’

‘Isn’t that …’ said Grafton, idly looking across at Kiki who was holding Justice in her lap.

Suddenly he felt a poke in the arm. He turned to look at Janet who whispered, ‘Don’t stare.’

‘What?’ mumbled Grafton. Janet frowned a disapproving frown which confused Grafton until he turned back again and realised with a shock what his bad eyesight had not initially revealed: the nanny was breast-feeding the baby. Lee-Anne, seeing his shock, jumped in to placate.

‘It’s okay, she’s a wet nurse. That’s why I got her. What were you going to say, Daddy?’

‘I, er –’ Grafton stammered recollecting his thoughts ‘– was going to say, isn’t that what whatsisname Richard Brainstorm and Efrem Muskrat are planning? Taking people to other planets?’

‘No,’ said Wayne, smiling derisively. ‘Brainstorm just wants to take people up out of the atmosphere and bring them back. Jesus, you can do that in a supersonic plane. And Muskrat wants to build a colony on Mars. It’s eighty degrees below zero and there’s no oxygen. He’s insane. What we’re building is the interplanetary version of a cruise ship. It’s a two-month interplanetary voyage in first-class luxury accommodation. You fly round the moon, and round Venus and back. One day we will include Mars if it’s on our side of the sun. And you see it all from the comfort of our viewing lounges. Five-star meals, nightly entertainment, and all the comforts of home while you travel a hundred million miles.’

‘That sounds wonderful,’ said Janet.

‘Expensive, I presume,’ said Grafton casually.

Lee-Anne and Wayne both seemed to light up at this question. Lee-Anne looked to Wayne for reassurance. ‘Do you want to tell them?’ she said.

Wayne smiled a Cheshire cat smile. ‘One hundred million dollars a ticket,’ he said.

‘My goodness,’ said Janet laughing. ‘That lets us out.’

‘Not necessarily,’ said Lee-Anne in a slightly cryptic tone.

‘That might sound like a lot,’ said Wayne, ‘but let me tell you: there are over three thousand billionaires in the world. A hundred mill is loose change to them. We’ll have no trouble filling the ship.’

‘How many will it carry?’ asked Grafton.

‘Two hundred and forty cabins – about four hundred people per voyage,’ said Wayne.

As Grafton cogitated on this, Wayne answered the question Grafton had posed for himself but was slow in working out.

‘Forty billion dollars per trip,’ he said. He leant back and nibbled on a slice of asparagus bread while his parents-in-law digested this fact.

‘And … when are you going to start building this … space ship?’ said Janet.

‘It’s being built as we speak,’ said Wayne.

‘It must be very large,’ suggested Grafton. ‘How will you …’

‘Get it off the ground?’ said Wayne with a sense of mischievous joy. He laughed slightly. ‘Ahh, we have devised a way,’ he said quietly as if they might be overheard there in the Everests’ backyard.

‘It’s really brilliant. Wayne is a genius,’ said Lee-Anne.

They waited to see if Wayne was going to explain further but he sat pat for a moment. ‘Okay, I’ll tell you,’ he said with just the slightest drop in volume as if Efrem Muskrat might be in the garden shed listening.

‘Up in space we’ve built a base. It’s a power plant with eight arms sticking out like spokes of a wheel. We call it the Asterisk because, you know, “Astra” means star and it’s … like an asterisk.’ Wayne looked around to check everyone was following. Satisfied, he continued, ‘Now, you know how they can launch the Space Shuttle off the top of a 747 jet?’

Grafton nodded, though he had no idea that they did.

“We’re going one better. We’ve bought eight Airbus 380s and instead of putting a space shuttle on the roof, we’ve put a hatch and a booster rocket. The passengers board the planes at a normal airport, fifty people per plane. But there’s no seats on the planes. There’s cabins like on a ship. And each plane has some special area like a restaurant, a bar, movie theatre, gymnasium … You know where this is going, don’t you?’

‘Of course,’ said Grafton, who was actually stumped.

Wayne grabbed a handful of knives and forks. ‘The planes take off. At 45,000 feet, the boosters fire and they go out of the atmosphere. They navigate to the Asterisk, jettison the boosters and each plane attaches to the end of a spoke making an …’ He arranged the knives and forks into an eight-sided polygon and looked around eagerly.

‘Yes! An octagon!’ he cried, confirming the answer no one had actually given. ‘Voila! You have a space wheel, just like the one in 2001 – A Space Odyssey.

This was another moment when Grafton wished the hell he had seen this iconic movie that people quoted so often but he got the idea: a big octagonal space station – made of planes.

‘The wheel starts to rotate, which creates artificial gravity, and the passengers can now move around the ship. They can travel up in elevators to the hub to go from plane to plane, eat in the dining room or go to the movies or just hang out in the observation galleries.’

Grafton had to admit it sounded incredibly possible.

‘We go round the moon, slingshot off its gravity, straight across fifty million miles to Venus – slingshot round again and back home. When we get back, we do it all in reverse. Easier than flying to Europe.’

‘Well, that’s very exciting indeed,’ said Janet with just the slightest hint of reservation.

‘It’s amazing,’ said Grafton, genuinely impressed that their pole-dancing, clown-oriented daughter was part of a one of the most startling developments in human history.

‘But that’s nothing! What about you?’ said Janet, slapping her hand down on top of his. ‘You’re going to be President of Australia!’

‘It’s not that big a deal,’ said Grafton without any false modesty. ‘I don’t get to do much. I’ll just be running one department – a kind of Department of National Wellbeing. I don’t even know what it’s going to do yet.’

‘I know. Mum said.’ Lee-Anne suddenly looked very intense. ‘That’s what I want to talk to you about. Soon. After we’ve checked into the hotel.’

‘Sure,’ said Grafton, wondering what fresh hell this might be.

‘Anyway, we better go,’ said Lee-Anne and with that she rose and, as if she were the queen, Wayne and the nanny rose as well and all departed, leaving the caterers to pack up.

Janet, who always made a point of showing appreciation to skilled people, politely thanked the cooking and serving staff. As the buffet table was being cleared, Grafton too approached the chef and complimented him on creating such a tasty though vegan lunch. The chef glanced up at him and then admitted sotto voce, ‘We put bacon in everything.’ Grafton nodded his approval.