Читать книгу Mussolini: History in an Hour - Rupert Colley - Страница 7

First World War

ОглавлениеThe outbreak of war in July 1914 saw Italy divided on whether to support the war or not. Since 1882, Italy had been part of the Triple Alliance with Germany and Austria-Hungary. But the treaty was a defensive one, and in 1914 Italy was able to argue that by declaring war on Serbia, Austria had acted aggressively, thus nullifying Italy’s obligations. Mussolini was firmly non-interventionist, arguing that, as an imperialist conflict, war pitted the working classes of one nation against those of another. ‘Let a single cry arise from the vast multitudes of the proletariat and let it be repeated in the squares and streets of Italy: down with war!’ Yet, within months, he had changed his mind. Not unlike Russia’s Bolsheviks, many within Italian socialist circles, including Mussolini, saw war as an opportunity for revolution and an overturning of Italy’s bourgeois government. Others felt that Italy should not miss out on the opportunity provided by war to enhance its prestige and assert its place in the world.

Again, Mussolini used his influence as editor of Avanti! to voice his views: ‘It is to you, young men of Italy … that I address my call to arms … Today I am forced to utter loudly and clearly in sincere good faith the fearful and fascinating word – war!’

Mussolini’s new view of war put him in conflict with Italy’s more moderate socialists and resulted in his expulsion from the party. ‘You cannot get rid of me because I am and always will be a socialist. You hate me because you still love me.’

Never to suffer a setback lying down, Mussolini responded by establishing his own newspaper, Il Popolo d’Italia, ‘The People of Italy’, which ran from November 1914 until the day Mussolini was removed from power in July 1943. One of his first editorials included his battle cry: ‘Blood alone moves the wheels of history’.

Mussolini founded his first political party, the Autonomous Fasci of Revolutionary Action, which, on 11 December, became the Fasci of Revolutionary Action, soon abbreviated to Fascists. He used, as the party symbol, later incorporated into the fascist flag, the fascio littorio, a bundle of sticks, bound together, with an axe protruding; a nod to the glory days of the ancient Roman Empire. (The word fascis is Latin for bundle.)

Britain and France, keen to encourage Mussolini in his support of the war, donated generous funds to the fledgling party, and Britain’s secret services even put Mussolini on its pay roll, paying him a wage of £100 per week.

Finally, on 26 April 1915, Italy, seduced by the Allies’ offer of various territories, including the Adriatic port of Fiume, signed in secret the Treaty of London in which Italy aligned itself to the Triple Entente. A month later, on 23 May, Italy duly declared war on Austria-Hungary and on Germany in August 1916.

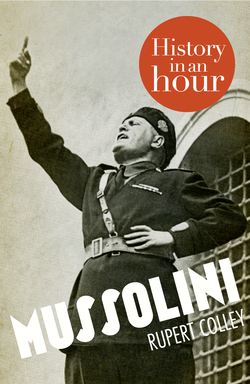

Drawing of Mussolini as a soldier, 1917.

Italy’s war was not the glorious affair its government had hoped for. Instead, hampered by poorly trained and generally unwilling conscripts led by inept and inexperienced officers, its armies became embroiled in a slogging match against the Austrians, most infamously during the course of twelve inconclusive battles along the River Isonzo. The war cost Italy over 650,000 dead, half a million missing and almost a million wounded. But the Italians finished the war with a Pyrrhic victory against the Austrians, albeit with much assistance from its allies, at the Battle of Vittorio Veneto, October–November 1918.

In September 1915, Mussolini had rejoined the Italian army where he was praised for his bravery and devotion, and reached the rank of corporal. On 22 February 1917, Mussolini was in a trench with colleagues when one of their grenades went off. ‘Flesh was torn; bones broken.’ According to his autobiography, he needed twenty-seven operations within the month. He returned home to recuperate and edit his Il Popolo d’Italia, and strengthen his political party, the Fascists. He still called for revolution and still spoke out against democracy but now his rhetoric was fuelled by patriotism and ultra nationalism rather than socialism and the cause of the working classes.