Читать книгу Mussolini: History in an Hour - Rupert Colley - Страница 8

Mutilated Victory

ОглавлениеDespite its victory at Vittorio Veneto, Italy was treated dismissively during the post-war talks at the Paris Peace Conference. The territories promised at the 1915 Treaty of London were not forthcoming, nor was Italy able to claim any of Germany’s former colonies. Italy’s prime minister, Vittorio Orlando, walked out of the talks, leaving Italy disappointed by its spoils of war. Heavily criticized by all sides of the political spectrum, Orlando was soon ousted from office. Italy, Italians felt, had been betrayed. It was, in the words of poet Gabriele D’Annunzio, a ‘mutilated victory’. (D’Annunzio, a fellow revolutionary, initiated several rituals that Mussolini later copied – the fascist, or Roman, salute, the black shirts, and the rousing speeches delivered from high balconies.)

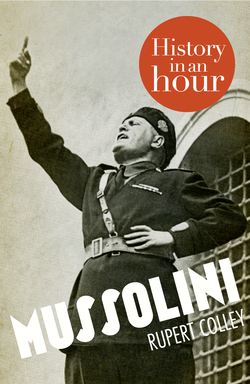

Benito Mussolini, 1920s.

On 23 March 1919, Mussolini, based in Milan, renamed his party the Italian Fasci of Combat. In his opening address, Mussolini claimed to be ‘opposed to all forms of dictatorship’. His views at this stage were firmly anti-socialist, anti-monarchy and anti-Church, and supportive of those who seethed at Italy’s mutilated victory. But while he may have had his loyal supporters, it was still an insignificant force nationally. In the elections of November 1919, his party failed to win a single seat. His opponents lampooned him by staging a mock funeral. With the socialists winning a third of seats in the Italian parliament, the Chamber of Deputies, Italy entered a period remembered as the ‘Two Red Years’.

From November 1919 until October 1922, Italy had a succession of four prime ministers and coalition governments each as powerless as the others to deal with the near-anarchy engulfing the country. As elsewhere in Europe, Italy suffered the post-war hangover as legions of demobilized soldiers returned home to a bleak and uncertain future. Crippling poverty, inflation, unemployment, national debt and disillusionment paralysed the nation as Italy descended into a period of chaos and political violence. Socialists, communists and fascists fought each other on the streets and in the villages. People were killed and communities terrorized as riots, strikes and disorder, both in the towns and the country, undermined the government. Groups of black-shirted fascists, squadrismo, paramilitary squads, intimidated and beat opponents, ransacked the offices of their rivals, including, in April 1919, that of Avanti!, and were soon resorting to arson and murder. It was, for Mussolini, the ‘iron necessity of violence’. Police, often sympathetic towards the fascists, stood by. A favourite punishment meted out by fascist mobs was to force opponents to consume large amounts of castor oil or swallow live frogs, tricks Mussolini had learnt from D’Annunzio.

In the national elections of 15 May 1921, Mussolini’s quest for power took a major step forward, or at least a ‘foot in the door’. His party, the Italian Fasci of Combat, joined a coalition of right-wing parties, the National Bloc, and managed to gain 35 seats of the total 535. In itself, this 6 per cent representation was insignificant. Of far greater import was that Mussolini had gained a seat in the Chamber of Deputies and was now a legitimate part of Italy’s political landscape. Needing to broaden his appeal, Mussolini, for whom principles always played second fiddle to expediency, now became pro-monarchy and pro-Church. The only constant was his hatred of socialism.

On 7 November 1921, Mussolini again renamed his party, now calling it the Partito Nazionale Fascista, PNF, the National Fascist Party. Word about Mussolini began to spread. Here was a man who promised to govern with a firm hand, to bring back order. At a time of near anarchy and when the threat of Bolshevism loomed large, Mussolini’s nationalistic message and authoritarian leadership found much support. Public opinion was beginning to turn.