Читать книгу Mussolini: History in an Hour - Rupert Colley - Страница 9

The March on Rome

Оглавление

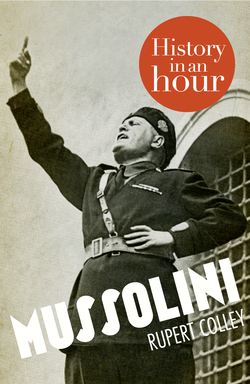

Mussolini and colleagues during the ‘March on Rome’, 28 October 1922.

On 24 October 1922, Mussolini’s fascists broke a strike organized by the socialists. A triumphant Mussolini spoke at a rally in Naples: ‘Either the government will be handed to us or we will seize it for ourselves by marching on Rome.’ The threat of civil war in Italy loomed large and Mussolini and his fascist party decided to stage a coup despite knowing they were no match for the Italian army. Luigi Facta, the prime minister, offered Mussolini a place in his government. As his supporters congregated, Mussolini refused; he had his sights set on higher things.

Facta, panicking, requested that the king declare a state of martial law and to allow him to use the army to squash the fascists now amassing outside the capital. The king initially agreed and then, fearing that such an action would spark a civil war, changed his mind. At a deeper level, the king harboured admiration for Mussolini and he knew large factions within the army’s command felt much the same. Victor Emmanuel, the ‘little sardine’ as Mussolini called him, also feared that if Mussolini took power by force he, as king, might risk being deposed in favour of his cousin, the fascist-supporting Duke of Aosta. Appalled by the king’s decision, Facta resigned.

Twenty thousand fascists began the March on Rome but stopped twenty miles north of the capital where, with the rain pouring down, half of them promptly returned home. Mussolini himself joined the march at various stages to have his photograph taken and be seen marching shoulder-to-shoulder with his men. The photos show Mussolini in typical pose – his jaw jutting, his chest inflated and his steely eyes fixed on his destiny. But there was only so much marching Mussolini wanted to do in the rain and instead he arrived in the capital by express train.

The king believed it was better to have Mussolini within his government than causing unrest from the outside so, as Facta had done, he offered the fascist leader a role in his government. Mussolini refused everything but the top job. The bluff worked, and on 28 October 1922, when the two men met, the king duly offered Mussolini the role of prime minister. Mussolini had achieved power not through revolution, as perhaps the romantic in him would have preferred, but via constitutional means.

The following day the march continued but with victory already won. This was more of a celebratory stroll than a revolutionary march. Elsewhere, the violence continued as jubilant fascists assaulted the beaten socialists.

Aged only 39, the 27th and, until 2014, youngest prime minister in Italian history, Mussolini’s years in power had begun. (He would also become Italy’s longest-serving prime minister.) In a speech delivered in Milan on 6 December 1922, he said, ‘My father was a blacksmith, and I often worked with him. He bent iron; but I have the harder task of bending souls.’