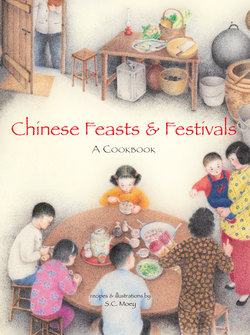

Читать книгу Chinese Feasts & Festivals - S. C. Moey - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPART ONE

The Chinese Feast

For food to be a truly joyous experience, there must be appropriate occasions to eat, drink and make merry. The Chinese are not short of such occasions. For more than 2,000 years, tradition has satisfied their desire to celebrate through a plethora of festivals, reunions, weddings and anniversaries.

Chinese festival feasts are purely family affairs. Gods and ancestors are invited to the party, but otherwise “outsiders” are generally excluded. The food served on these occasions is a combination of symbols and sumptuous flavors, a spiritual celebration and an earthly pleasure. Dishes suggesting wealth, luck and splendor by way of their appearance or because they rhyme with certain auspicious Chinese words, simmer or saute in pots and woks. Proportions are generous as custom dictates that one should not stint at the festive table. Abundance brings luck. For families of modest means, surplus is restricted to these special occasions. Hence festivals, with their promise of cornucopia, are eagerly awaited.

Before man can enjoy, the gods must be nourished. In Chinese homes, gods and ancestors take the form of tablets—red wooden or metal rectangles mounted on the wall, fitted with jars or cylinders for candles and joss sticks. Calligraphic characters in black or gold identify the ancestors. Three “protectors”—the Heavenly Emperor or Jade Emperor, the Earth God and the Kitchen God—are installed to look after the home. People in need of “extra protection” reinforce these with additional help from the God of Wealth, the Warrior God (Guan Gong) and the Goddess of Mercy (Kuan Yin). Food and wine are set on a tray or table before each tablet. The most efficacious offerings are chicken, roast pork, fresh lettuce, spring onions, celery, rice, sweet rice cakes and fruits—all symbolic of life and its attendant virtues and values. The same delicacies may be offered to the three household gods, who are worshiped in turns. Extra places are set in case a god has company. Popular imagination assigns two bodyguards to each celestial VIP.

Traditionally, the lady of the house conducts the offering rites. Once the food is set, the protector and his entourage, if any, are welcomed with two red candles. This is followed by an offering of joss sticks together with prayers and, if one desires, divination sticks or blocks are cast to determine the visitors’ wishes and receive their blessings. A suitable time is allowed to pass during which the invisible guests eat and drink. The entertainments over, they are given a send-off with a ceremonial burning of an assortment of joss papers (yim po in Cantonese) conveying good wishes and a safe journey.

For the ancestors, customarily the last of the protectors to partake of the feast, an even larger spread is laid out. Again, three places are set, though in some households the settings can reach ten or twelve. The family patriarch, proffering joss sticks, leads the way. Other males take precedence over females. Appeased, the ancestors feast in a fashion peculiar to the gods, unseen and undetected by mortals.

Protection is renewed when the divine have departed. Secure in the knowledge, members of the household gather and enjoy the feast they have shared with the gods and the ancestors.