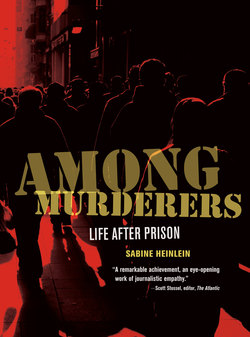

Читать книгу Among Murderers - Sabine Heinlein - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER TWO

At the Garden

Adam was released to the Castle at the end of April of 2007. He had served thirty-one of his twenty-five-years-to-life sentence for two counts of second-degree murder, robbery, conspiracy, and an attempted escape. I met Adam at the Albany advocacy day in May where I had also met Angel. What I first noticed about him was his meticulous attire. Fashion had always been very important to Adam. A seventy-two-year-old Muslim convert, Adam wore classic secondhand wool sweaters and wire-rim glasses that complemented the color of his silver beard. His wardrobe showed off his athletic build and broad shoulders. His graceful posture, the golden ring on his right hand, and his gray beard and glasses made him look wise and dignified. When he was handed the microphone, he spoke with gravity, confidence, and strength. Because of his aura it took me a few weeks to approach him. When I finally did, I was surprised to find a man who laughed easily and readily shared his sorrows and pain.

Adam experienced his surroundings with unusual intensity. He was aware of every step he took and wondered constantly whether the people around him were as aware of him as he was of them. Adam and I were worlds apart, yet I could relate to him. Aside from the glaringly obvious differences, Adam and I shared certain qualities. We were connected by a state of constant alertness. We both liked to “analyze.” Our vigilance protected us and kept us in check, but it also made us slightly neurotic. We moved on thin ice.

Adam’s observational skills had benefited him in prison. They gave him something to do, kept him safe, and allowed him to teach prisoners in need of his various modes of introspection. In prison he established “coping programs for lifers,” people who, like him, served indeterminate life sentences or who were sentenced to life without parole. His classes addressed the needs of prisoners that the prison system neglected: How does an individual who was sentenced for murder come to terms with his legacy? And how does he go about the possibility that he might have to spend the rest of his life locked up in a vacuum while outside a world is unfolding, becoming more and more foreign each passing year? Can you recover and be reformed when you might have to spend the rest of your life in prison? No one else seemed to discuss these questions.

Adam could feel an ever-increasing void. He was on his own. Prison threatened to draw him into the big, black hole of timelessness and despair. He decided to deal with it himself. Adam believed that there was a way an individual could actually rehabilitate himself. No, not could—it was imperative. That was his responsibility after having committed such horrendous crimes.

One of the first things Adam told me was that he had come to terms with the fact that he would die in prison, and now he missed his “family,” his fellow lifers. “I can do this. I can do this till I die,” Adam said about prison. “This is no big thing to me.” That was his mantra. He kept a scrapbook in which he pasted articles and pictures of places lost, of places he wasn’t able to visit. The outside world was no more than a figment of his imagination—hope and hopelessness reduced to strips of paper and glue.

When Adam finally did return to the outside world, he was stunned. He wanted to see as much as he could, lamenting that he didn’t have much time left. He had to hurry because of his looming death.

During the two years that followed Adam’s release, we embarked on excursions in Brooklyn, Manhattan, the Bronx, and Queens. One of our early journeys led us to the Brooklyn Botanic Garden, which Adam remembered from his childhood. When he was eleven or twelve, he would walk or take the trolley from his home in Bedford-Stuyvesant to the park. He had been a loner as a child and always loved nature, trees, flowers, and birds. Sometimes in the summer he would go to the Garden to sleep under a tree. He didn’t know where his love of nature came from; all he knew was that none of the other kids came along.

When I arrived at the Botanic Garden at 10:30 on a Sunday morning, Adam was sitting on a bench across the street on Eastern Parkway. As always, he wore matching clothes and laughed happily when we said, “Hi.”

At the Steinhardt Conservatory, a greenhouse complex that simulates different climates and vegetation from around the world, Adam touched everything he saw. The fruits on the cactus in the Desert Pavilion looked like little strawberries. Adam muttered, reading the plaques aloud. It was almost as if I weren’t there.

“Endurance and avoidance,” he read, referring to the characteristics of cacti. “The survival of the fittest . . . Hmm.” Adam always hummed when making space for more thoughts to come.

He admired the Mohintli cactus’s slender, velvety leaves and its bright orange blossoms. Touching the hairbrush cactus, he yelped, “Ouch!” Then he laughed, giving me a quick glance.

In the Tropical Pavilion he wondered about the Golden Eye Grass, an inconspicuous-looking plant with a poetic-sounding name. And how different mahogany looked from the outside than from the inside! One couldn’t have predicted the reddish sheen it assumed when crafted and polished.

Adam’s hands slid down the skinny, smooth stem of a breadnut tree. Hanging down in long tassels, the fishtail palm’s berries looked like dreadlocks. Adam poked into the stem of the Musa brazilia, a banana plant. The plant had a sore, its plasticky skin peeling off and sap running down its trunk.

The papaya tree bore large, ripe fruit.

Adam smelled the Clerodendron, which couldn’t have been more alien in appearance. In the middle of a bright-pink, star-shaped flower it proudly displayed a royal blue pearl. The dancing girl ginger stretched her little arms as if to reach out to the carnival flower, whose purple blossoms looked like a jester’s hat.

Adam read the description next to the cocoa tree and huffed in disbelief. Fifteen seeds to make just one cup of coffee? The flower next to the coffee tree looked like an open mouth. Just steps from the tree and the open mouth was the cola tree, whose seeds flavor the soft drink. “In African culture,” Adam read, “a cola tree is planted for every newborn baby, who then remains its lifelong owner.”

No cola tree, or anything else for that matter, was “planted” for Adam. What he seemed to own most intensely were his crimes. They were always present, an open wound, throbbing with each step he took. Adam did not need to be prodded to talk about them. They always accompanied us, even on this sunny day in the park. Adam was stuck between worlds.

Adam met his three partners-in-crime in the early 1970s, when he was serving yet another stint for robbery at Green Haven Correctional Facility, seventy miles outside of New York. Just eighteen months after his release, the team started to plan an intricate robbery of a movie house in Manhattan. Although Adam liked “sticking up,” he preferred the planning phase to the actual execution.

Kevin, one of the robbers, worked at the movie theater and knew its procedures. The idea was to rob the theater on a Monday morning when two armed guards regularly arrived to pick up the approximately $20,000 in weekend receipts from the safe. The crew did numerous practice runs to the theater. They tied up groups of volunteers to see how long it would take. They staged every part of the robbery to the last detail. But something went wrong.

The turn-of-the-century theater was adorned in art nouveau style, with florid oak paneling and murals depicting classical heroes. Its main auditorium was a massive ellipse with a domed ceiling and elaborate plasterwork. But in 1976, as the neighborhood declined into prostitution and crime, the magnificent movie house fell on hard times.

At first things went according to plan. Kevin let Bobby and Adam into the theater through the back exit while Richie waited in the getaway car. As the theater employees arrived for the morning shift they were tied up with cut pieces of clothesline and taken to the basement, where Bobby was assigned to watch over them. The media described the robbers, who wore ski masks and carried sawed-off shotguns, as polite and considerate. The men told their hostages not to worry and assured them that they weren’t going to be hurt or robbed. A hostage later reported that one gunman told him everything would be okay and that he would live to read about it in the paper.

Adam was in the basement to check in with Bobby and the hostages when he heard shots echo down from the theater.

BangBangBangBang!

“Shit!”

Whenever Adam recalls the shooting, shit is the word that best sums it all up. “Shit!” he said now, more than three decades later. He grabbed his head in despair as if the event were transpiring as we spoke. Adam had never used his gun. He never carried a gun when out on the streets. When he carried a gun during robberies, it was rarely loaded.

In planning the stickup Adam had not taken into account that one of his gunmen might lose his nerve. Kevin panicked when the guards held their guns in his direction.

“Don’t raise the shotgun!” he yelled when the two guards entered the auditorium, where he was waiting to take them hostage. “Don’t raise that fucking shotgun!”

But the guards might not have even known where exactly the yelling was coming from or where the intruders were hiding. Kevin snapped.

When Adam came back upstairs, he saw the guards on the ground. The floor was covered with puddles of blood, and the mirrored walls were plastered with pieces of tissue. The guards screamed and reached out their hands, begging Adam for help. Their faces were barely lit by the auditorium’s running floor lights. Adam was torn. He wanted to help, but at the same time he knew that he had to get out of there as quickly as possible. Pedestrians had already started to crowd the sidewalk, and one of the hostages had managed to call 911.

The guards both died shortly after reaching the hospital. Adam and his partners were apprehended a few weeks later. After the robbery Adam collected the newspaper clippings about the victims: Thomas Bell, fifty-five, and José Rodriguez, sixty-five—two round, white faces peering out at him from yellowing paper. Both men, captured by a slightly elevated camera, wore grave smiles. They looked as if they were anticipating what was going to happen. Even unharmed, the men looked like beaten dogs. Adam kept the articles and photographs stowed away in a folder in his cell. His victims’ pictures and their names had carved themselves into his mind. Thomas Bell and José Rodriguez were with him for good.

The firewheel tree looked as if in flames. Lyrical names—butcher’s broom, honeybells, star jasmine, cape cowslip—made me think of taxonomists, peculiar men housed in the secluded bowels of august buildings, presiding over the ordering and naming of life. Names are crucial in comprehending the world. They ensure that plants and people who might otherwise be forgotten remain with us. But names are also a curse, as they inspirit things that we would rather not remember. Once you start naming your victims, the real struggle begins.

A squirrel skidded treacherously along on one of the pipes above us. Wherever we went, we could hear birds chirping. At some point, however, it became difficult to distinguish the call of an exotic species from the screech of a malfunctioning fan. When I shared my doubts with Adam, he was reminded of prison. You could take Adam to the most exotic places in New York and in no time he would be talking about prison. For the longest time he had yearned to be free, but now that he was free, he sometimes missed prison.

In the 1960s and 1970s, before Adam committed the crime that resulted in his being labeled a murderer, the main goal of incarceration was rehabilitation, not punishment. Back then, prisoners were allowed to keep birds and cats. At Sing Sing, where Adam had served a previous sentence for attempted robbery, he fed shrimp to a cat. The next day the cat brought three other cats with him. At Elmira, Adam and the other inmates kept parakeets and gave them Kool-Aid, which, Adam told me, colored the birds’ feathers. He advertised his crazy Kool-Aid birds in specialty magazines, and people from the outside came inside to buy them.

Blastin’ Berry Cherry, Kickin’-Kiwi-Lime, Man-o-Mangoberry, Pink Swimmingo, Scary Black Cherry, Sharkleberry Fin? Adam told me that the buyers were furious when, after several weeks, the birds’ colors began to fade. They complained to the prison administration, and the commissary stopped selling Kool-Aid.

The birds kept the men company. Adam put up pieces of cheesecloth in front of his bars and let the parakeets fly around in his cell. The man in the next cell played his guitar, and Adam remembered how his parakeets used to line up to sing along.

Adam’s fantastic prison story ended on a sad note. One morning, he jammed his foot into his shoe and right onto a sleeping parakeet, killing it. “Oh, man,” Adam sighed at the Botanic Garden as he recalled the accident. “I felt baaad.”

I was struck by how repulsed Adam was by having taken this little life, however small. How bad must he feel for having caused the deaths of Rodriguez and Bell! Whenever the topic came up—and it often did—he said, “I had no intention! It never entered my mind that anything like that would go on. All those years . . . I never shot anybody. If there would have been anything to change that situation I would have.”

I was reminded of this story when I later dug out newspaper articles about Adam’s crime. One article quoted a hostage as saying that one of the gunmen allowed them to smoke and asked whether the strings around their wrists were too tight. I now wondered whether the person who expressed this concern was Adam. Maybe Adam wouldn’t have pulled a gun had he been in Kevin’s place. Maybe he wouldn’t have lost his cool. Either way, he had planned the robbery and failed to consider its possible consequences; he was complicit in the guards’ deaths. And instead of facing up to what he had done, he ran from the law until he was captured. There were worlds between Adam’s thinking now and his attitude thirty years ago. Now he constantly expressed his shame, guilt, and remorse and his wish to be able to turn around and change his past. Somewhere along the line he must have learned to face his transgression. What he had yet to face was freedom, the strange bright world he entered after thirty-one years in the dark.