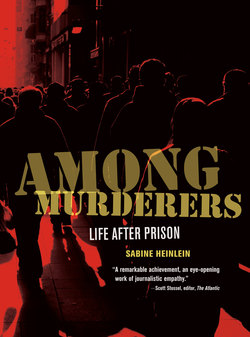

Читать книгу Among Murderers - Sabine Heinlein - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

By talking and hanging out with murderers, child molesters, burglars, drug dealers, and robbers, I entered a parallel world unfamiliar to most of us. Although these former criminals are among us, our lives rarely intersect. What is life like for those who have spent several decades in prison and are released into a world in which people and places they once knew have ceased to exist? What is it like to start over from nothing? And did prison succeed in making them see the error of their ways?

I was still working on my master's degree at New York University's Carter Journalism Institute when I set out to learn how New York's growing net of reentry organizations helps former prisoners ease back into freedom. The goal of these agencies is to rehabilitate their clients—to restore their livelihoods and prevent them from going back to prison. After spending large parts of their lives locked up, these men and women need a roof over their heads, medical care, and a job—any job, really.

In 2007 I began to attend reentry events where advocates, ex-cons, and their family members discussed the challenges of life after prison. I talked to the clients and staff of reentry organizations with Pollyanna-ish names like STRIVE (Support and Training Results in Valuable Employees), CEO (Center for Employment Opportunities), and the Fortune Society. Most clients of the Fortune Society, STRIVE, and CEO were people with extensive rap sheets—and most were out of luck. Few had ever learned to strive for anything, and it is safe to assume that they will never become CEOS. What they needed most was individual attention and love.

One man I spoke to had forgotten how to turn on a faucet after living in a prison cell for twenty years. When I accompanied another recently released man on his walk through the city, he almost got run over when crossing the street, not once but five times in half an hour. His sense of public space had atrophied so completely that whenever he managed to avoid the traffic, he bumped into other pedestrians. I once tried to show yet another ex-offender how to turn on a PC, go online, and check his emails. It would have been easier to teach a child how to drive a car. Freedom was a relief, surely, but it was also a challenge. It wasn't something that could simply be embraced. The men had to painstakingly learn how to master this freedom. I noticed that no one had ever addressed those seemingly minor obstacles of prisoner rehabilitation and reintegration; this is how the idea for this book came into being.

A growing number of reentry organizations backed by public and private funds have tried to smooth the individual's return to society. In the last decade reentry has become a hot-button topic. Reentry resource centers, reentry round tables, reentry institutes, and reentry initiatives have popped up across the country. The work of advocates and legislators has yielded impressive results: The Second Chance Act was signed into law in 2008. Aimed at improving the lives of ex-offenders, it authorizes federal grants to government agencies and nonprofit organizations for employment assistance, substance-abuse treatment, housing, family programs, mentoring, victims’ support, and other services that may help reduce recidivism. In 2009 New York's tough drug laws, which had been signed into law by Governor Nelson Rockefeller in 1973, were revised to remove mandatory minimum sentences.

But despite the reentry movement's recent successes, the term reentry sounds like wishful thinking. At the reentry meetings I listened to advocates endlessly introduce services, strategies, and legislative goals. At the end of these lectures a man or woman of color would usually stand up, trying to share his or her sad life story. “I just came home after serving fifteen [or twenty or thirty] years,” the person would begin before spiraling into a rambling tale of alienation. Eventually someone from the panel would cut off the speaker, leaving the rest of the story unheard.

Naturally, the phenomenon of ex-prisoners attempting to become part of our society begged for a name, but “reentry” seemed hopelessly removed from what it really meant to be released from prison. There was nothing guided or measured about becoming part of mainstream society. Besides, did these men and women really succeed in “reentering” our world?

In 2009 almost 730,000 people were released from U.S. prisons.1 Many ex-prisoners return to the same crime-ridden and impoverished neighborhoods that raised them, and a very select few find permanent employment. Two-thirds of them land back in prison.2

Incarceration affects a disproportionate number of men of color. More than half of all incarcerated men are African Americans, and greater than 20 percent are Hispanics.3

These harrowing statistics and my own personal experiences with ex-prisoners and reentry organizations made me wonder: How can we rehabilitate these disenfranchised masses? How do contemporary institutions approach rehabilitation, and what role does the general public play in this process? Few of us consider the individual who bears the brunt of this burden. What attempts at rehabilitation does the ex-prisoner himself (or herself) make? How do ex-prisoners learn to navigate their freedom? What resources can they count on, and what obstacles do they encounter? While society may be comfortable talking about racial and social disparities in the abstract (or in public policy terms), in this book I talk about these issues by looking at real human beings who have faced the challenges of reentry.

Besides the commonly cited objective of reducing recidivism, no one discusses what constitutes successful rehabilitation. Is it simply a matter of keeping an individual out of prison and of finding him or her a job? We will see that this issue encompasses a number of mundane aspects, as well as several significant moral ones. The life stories of the three men of color, men who spent several decades in prison for murder and were released into the hands of the Fortune Society in 2007, illuminate these complex questions.4

CONNECTING

I must have interviewed at least fifty former prisoners before I finally found a subject: Angel Ramos. Angel's horrific crimes and his extraordinary journey to freedom, his willingness to let me accompany him to his programs and to share with me even the most mundane details of his life, made him a perfect subject for this book.

Angel was released in March 2007 after having served twenty-nine years in prison. At eighteen years old he had taken one life and nearly two others. After he was caught, he tried to escape from New York's Rikers Island. Considering his journey, he was remarkably upbeat and optimistic. Most important, maybe, wherever he went, people seemed to like him. A short, sturdy man, Angel was of Puerto Rican descent and had grown up in East Harlem, the neighborhood where he committed his most heinous crime. He had smooth brown skin; a mustache; and short, curly hair. He often wore a dark suit, a bright shirt, and a wildly patterned tie. Angel was witty and charming, and he looked at the world with wide eyes. He thought of himself as someone special, someone whose story needed to be told.

Shortly after his release, Angel met Adam and Bruce at a halfway house, and the three became friends. They had few things in common beyond the fact that they were intelligent men of color who had served several decades behind bars for murder.

In his early seventies, Adam had spent thirty-one years in prison for murder, robbery, conspiracy, and an attempted escape. He was released in April 2007, one month after Angel. I first saw Adam at one of the many reentry events he attended. Although I don't remember the particulars of the event, I do remember his presence. His forehead was deeply furrowed. His graceful posture, gray beard, and thinly framed glasses lent him an aura of wisdom and respect. To me he looked more like a retired sociology professor or a famous jazz musician than an ex-con. Despite his solemn disposition, he often broke out in spontaneous laughter. While genuine, his laughter was also deceiving. Right at the start Adam told me that he had difficulties taking off his “prison armor.” He couldn't “find the zipper.” However much he tried, Adam couldn't find his way “home.”

In May 2007 Bruce joined Angel and Adam at the Castle, a West Harlem halfway house founded by the Fortune Society. When he was in his late twenties, Bruce shot a stranger following an argument; he spent twenty-four years in prison. Bruce is the most introverted of the three men. Compared to Angel and Adam, he is intimidatingly tall. Trying to make himself look shorter, he walks with a slight hunch. His head is always shaved smooth. At his height, who would want to add an extra inch? He often wears a baseball hat that looks comically small on his large head. Try as he might to appear shorter, he remains six foot six. Bruce is quiet and reserved. He speaks primarily when addressed and even then only sparingly. Bruce seems to have few illusions about life yet strides ahead with surprising balance.

Angel, Bruce, and Adam began their new life at the Fortune Society's Castle. A prominent reentry organization in New York, Fortune, as it is commonly known, has been around since 1968 and has helped thousands of former prisoners navigate the welfare system and find housing and work. In three New York locations Fortune offers a variety of services, including computer tutoring, substance-abuse treatment, cooking classes, and father- and motherhood programs.

Angel, Bruce, Adam, and I are as different as can be. I grew up in an upper-middle-class family in a suburb of a Bavarian city not much bigger than the suburb itself. I moved to Hamburg right after high school and immigrated to the United States in 2001. When I was growing up, the darkest shade of skin in my town was that of the two dozen gypsies that camped out on a field at the city limits for a few weeks every year. The common opinion among the permanent residents was that the gypsies were liars and criminals. Clearly, the gypsies didn't want to integrate. Unhappy with the little town's rigidity and impregnability, my mother instilled in me a sense of doubt in stereotypes. At an early age I learned to defeat my fear of the “other” through curiosity. So in a sense, my work as a journalist is a response to my mother's desire to break out of her small world and broaden her view.

As an adult I realized that part of this childhood “exercise” called for the augmentation of empathy for people who can't find empathy from society at large. However naive or impossible it may seem, I wondered what would happen if empathy was our first response to people who find themselves at the margins. (Later I learned that there actually is a movement named “journalism of empathy.” Ted Conover, the author of Newjack, has taught a course by that name at NYU, as did Alex Kotlowitz, the author of There Are No Children Here, at Northwestern University.)5 In my career as a journalist I have spent time with all kinds of people—homeless alcoholics, people with mental illnesses, blind teenagers, clowns, and fortune-tellers, to name just a few. I didn't like or agree with every individual I met, but without empathy I would have never been able to understand them. I think we can learn to respect each other, even while admitting our ambivalence or disapproval.

WHY MURDERERS?

In terms of empathy, murderers are obviously very low (if not lowest) on our list of priorities. Murder is universally considered the most serious crime of all, and the violent loss of a human life inflicts endless grief on the victim's relatives and friends. It is hard to look a murderer in the face. It is infinitely more comfortable to reduce murderers to numbers than to try to understand their lives. Yet considering the rising number of murderers being released from prison, it becomes harder and harder to turn away.

New York's murder rates have decreased dramatically over the last decades. In 2007 the rate had dropped to fewer than five hundred killings a year, its lowest point in more than forty years. But forty years ago murder rates in the city began to rise. (In 1971, for example, 1,466 were killed in the city, and in 1990 the murder rate peaked at 2,245.)6 My main characters all committed their killings at a time when these statistics were escalating. After serving twenty, thirty, or even forty years in prison, the murderers are returning home to a culture less inured to their crimes.

Given my goal of displaying the different dimensions of rehabilitation, I became particularly interested in people who had spent large parts of their lives behind bars. An extreme crime with an extreme sentence most clearly highlights the issues with which ex-cons commonly struggle, and the longer a person has been imprisoned, the more overwhelming freedom becomes. An extreme crime and an extreme sentence require more complex individual, institutional, and societal strategies of rehabilitation.

One issue that came to interest me in particular is the moral ramifications of murder. No other crime is so transformative, inside and out. Angel once said to me, “Murder is the ultimate crime. Victim and murderer both can't recover.” His comment made me wonder whether a murderer can ever be fully rehabilitated. We will see that a murderer's rehabilitation may or may not involve a lifelong struggle with guilt and with society's inability to forgive. My subjects’ stories demonstrate that murderers return to our society with a huge amount of psychological baggage and that attempts at rehabilitation and integration put an enormous strain on private and public agencies, on families, and on the individuals themselves.

Although there are many academic studies, memoirs, and journalistic accounts exploring the long-lasting consequences of violent acts on victims, there is little information on the effects that crime and long-term incarceration have on the murderer and on the society to which he or she returns. And to take a step back: murder rarely happens without forewarning. Through three individual narratives my book shows that there are a slew of predictors leading up to the crime. These predictors, in turn, provide important clues about how such a murder could have been prevented. While individuals, family, school, community, and society may have failed at prevention, the examples in this book might help us understand what is necessary for a criminal's rehabilitation. As such, rehabilitation is linked to the criminal's life before prison.

From a public policy perspective alone, it seems obvious that we should care about the 730,000 men and women released from prison each year. If millions of Americans were affected with a dangerous virus that cost us billions of tax dollars, destroyed families and livelihoods, and left a large part of the population homeless and mentally ill, no one would question the government's attempt to find a long-lasting solution. I think we should care about Adam, Bruce, and Angel not only because their stories illustrate the outcomes of applied public policy and criminal justice but because they address our values as human beings and as a collective society. Who deserves forgiveness, and who is willing to forgive? Do we consider punishment temporary or eternal? Should our personal history ameliorate the consequences of our errors? How much can we blame our parents and our environment for our missteps as adults? These vital questions pertain to all of us. I wrestle directly with these questions through the detailed psychological portraits I have drawn of Angel, Bruce, and Adam and show that one answer doesn't suffice. Rather, each individual deserves his or her own consideration and set of complex answers.

OF REHAB—AND CORRECTIONAL QUACKERY

This is neither a book of public policy nor one of criminal justice. It is a work of literary nonfiction that delves into the everyday lives and emotional struggles of three formerly incarcerated individuals. It explores their journeys to freedom and their various modes of rehabilitation. Not wanting to interrupt the narrative flow, I decided to deliver a brief excursion into America's conflicting philosophies of crime and punishment here.7 Through their rehabilitative paths, Angel, Bruce, and Adam illustrate and enrich the theories that attempt to define and manage them.

In Correctional Theory: Context and Consequences criminologists Francis T. Cullen and Cheryl Lero Jonson define rehabilitation as “a planned correctional intervention that targets for change internal and/or social criminogenic [crime-producing] factors with the goal of reducing recidivism and, where possible, of improving other aspects of an offender's life.”8 (Note that the primary focus lies on the reduction of recidivism; I will return to the second goal, the “other aspects,” which I consider of equal importance, a bit later on.) Cullen and Jonson argue that “the belief that a core function of prisons should be rehabilitation is woven deeply into the nation's cultural fabric.”9 In other words, if America wants to stay true to itself, it has to revive the rehabilitative ideal, which was stamped out by the draconian get-tough-on-crime policies of the past decades.

In colonial times crime was not dealt with through prolonged prison sentences or correctional institutions as Bruce, Adam, and Angel experienced them. In his seminal book The Discovery of the Asylum, historian David J. Rothman writes that suspects accused of witchcraft, blasphemy, or idolatry, for example—the definition of crime then was based on the Bible—were held in small jails only until they were tried.10 The accused was then publicly humiliated, whipped, fined, perhaps expulsed from the colonial settlement, or even hanged. The three most powerful weapons of crime prevention were thought to be family, church, and community.

The period of enlightenment and nation building coincided with an enormous increase in the diversity and population density of America's cities. (Rothman notes that New York's population grew fivefold between 1790 and 1830.) The colonial methods of punishment were considered barbaric, and a new movement emerged that was concerned with the origins and treatment of criminal behavior. The severe colonial criminal codes were deemed a cause and thus amended, and incarceration was seen as a humane alternative to the old codes. America built its first prisons at the end of the eighteenth century. An offender's sentence was matched with the severity of the crime. When this approach failed to reduce crime, criminal behavior began to be attributed to dysfunctional families and the environmental factors that plagued American cities, such as prostitution, alcohol, theaters, and criminal opportunities. Authorities decided to create special environments, free of corruption, to reinforce the functioning social order. In 1820, two separate penal movements emerged: The Auburn prison established the so-called New York or Congregate System, which aimed to reform offenders through hard labor, religious training, obedience, and silence. At the Philadelphia prison, where the Separate System originated, total isolation and silence were implemented to instill repentance. The purpose of both systems, which were deeply rooted in Christianity, was to rehabilitate the wayward.

After the Civil War America's prison system was in a state of crisis. Unbearably crowded and disease ridden, many prisons had to give up on their concept of solitude, silence, and contemplation. This endemic problem, criminology expert Alexis M. Durham writes, “continues to bedevil modern correctional operations.” He points out that the psychological impact of living in crowded conditions “may not appear until after the inmate has returned to society and is no longer under careful observation.”11

In 1870, leading correctional thinkers convened at the National Congress on Penitentiary and Reformatory Discipline in Cincinnati and suggested a number of principles to reform the system: Prisoners were to be carefully classified; more rewards than punishment were to be administered; prison officials should receive special training; inmates were to be treated on an individual basis and should have access to education and work training. “By providing them with work and encouraging them to redeem their character and regain their lost position in society,” offenders were supposed to be reintegrated into society.12 The creation of indeterminate sentences (which were to make sure that a prisoner was released as soon as he was rehabilitated), the parole board, parole and probation officers, and the juvenile court were all direct results of what came to be known as the “Rehabilitative Ideal.”

Criminologists Cullen and Jonson note that the rehabilitative ideal reached its peak in the 1950s and 1960s, when a broad range of treatment programs, including group counseling, college education, behavior modification, work release, and work training programs were introduced and community-based treatment programs were championed.13 Yet the unfettered belief in rehabilitation waned in the following decades. Cullen and Jonson attribute this decline to the social and political turmoil of the 1960s and 1970s, a period marked by the civil rights movement, the Vietnam War, Watergate, urban riots, and an enormous increase in crime. While liberals grew suspicious of the unrestricted discretion of governmental institutions (such as courts, prisons, and parole boards), conservatives believed that criminals were “coddled” and that the public was being put at risk. With his notorious 1974 publication, “What Works? Questions and Answers about Prison Reform,” criminologist Robert Martinson fanned the flames. Citing eighty-two studies on rehabilitation programs and recidivism, Martinson concluded, “With few and isolated exceptions, the rehabilitative efforts that have been reported so far have no appreciable effect on recidivism.”14 In 1975 Ted Palmer published a comprehensive rebuttal to Martinson's findings, reexamining the studies and concluding that 48 percent of the programs studied were, in fact, reducing recidivism.15 But Martinson's “nothing works” report was “the straw that broke the camel's back,” according to criminologists Edward Latessa and Alexander M. Holsinger.16 Its tone would define the law-and-order movement for decades to come.

Although not all treatment programs were eradicated, rehabilitation as the dominant correctional philosophy was replaced with a belief in deterrence, “incapacitation,” and “just deserts.” The notion of deterrence is rooted in the belief that punishment in itself reduces criminal behavior. It assumes that people are rational and seek to avoid pain. Incapacitation follows the idea that crime can be prevented by simply locking up criminals. “Just deserts” proponents don't concern themselves with preventing or controlling future crimes. Advocating mandatory sentences that don't make a criminal's release dependent on the discretion of judges and prison officials, they seek to create exact sentences that punish the criminal act: regardless of circumstances, finances, race, or rehabilitative development, each criminal receives exactly the same sentence for his or her particular crime.

It is important to point out that rehabilitation, deterrence, “just deserts, “ and incapacitation are not mutually exclusive. Angel, Bruce, and Adam experienced not one coherent guiding philosophy but rather a hodgepodge of competing philosophies that have been applied and absorbed at random.

While job training and educational programs for inmates are still available and while prison ministries continue to go strong, the rehabilitative ideal was largely pushed aside by these new philosophies and, significantly, vengeance. A tough-on-crime stance, resulting in mandatory sentencing, three-strikes laws, and the mass incarceration of people of color in particular, determined the approach to criminal justice for decades to come. Bruce, Adam, and Angel were kept in prison far beyond their mandatory minimum sentences. The decision of the parole commissioners was based on some vague notion that the three men's dispositions were “incompatible with the public safety and welfare.” Looking at Angel's parole transcripts, I wondered what could have gotten him out of prison after fifteen years, when he first became eligible for parole. He had gathered support letters, an education, and job training certificates to prove that he was no longer a menace to society but was denied parole the first seven times he went in front of the board. Apparently, deterrence, incapacitation, and programming had not yet achieved what they were supposed to do. This case again begs the question of what constitutes successful rehabilitation in the minds of the administration—and in our own.

One of the most obvious problems with the philosophies of deterrence and incapacitation are that what deters one person does not necessarily deter another. In fact, Bruce was not deterred by the prospect of prison. Sadly, he was familiar with it from the street and from his own family. Bruce's example also reminds us that rationality and self-control are not generally strong traits in criminals.

The problem with “just deserts” is that it is difficult to predict who will commit crimes and when; predictive sentencing prevents offenders from being released on good behavior and, overall, results in longer sentences. While proponents of incapacitation may argue that locking up offenders and throwing away the key does, indeed, lower crime rates, opponents retort that these rates are only lower compared to a “nothing works” approach. If a similar amount of money were to be invested in evidence-based correctional interventions, the crime rates might actually decrease.17

When Adam was incarcerated in 1976, there were fewer than 263,000 people in prison in the United States.18 Today there are 2.3 million Americans in prisons and jails and another 5 million on parole and probation.19 America's correctional system is once again in a state of crisis. “The prisons are ‘overcrowded,’ we are told (and, in fact, courts have ruled). ‘Overcrowding’ is a euphemism for an authoritarian nightmare,” writes Christopher Glazek in his comprehensive and eye-opening article on the topic. Detailing the manifold obstacles facing ex-offenders, he adds, “Once you go to prison, you never really come back.”20

Spurred by these daunting numbers, as well as by financial, humanitarian, and public-safety concerns, the last two decades have spawned a growing movement of criminologists who advocate for evidence-based rehabilitation. Under the assumption that “crime is chosen but not according to some vague notions of rational choice,” professionals have worked to identify “criminogenic risk factors” (such as antisocial values, a dysfunctional family background, criminal peers, risk seeking, and impulsiveness) that have been shown to correlate with crime and recidivism and, most important, that can be changed.21

In their influential 2002 article, “Beyond Correctional Quackery—Professionalism and the Possibility of Effective Treatment,” criminologists Latessa, Cullen, and Paul Gendreau point out that many of the correctional treatment methods of the last decades are not based on solid scientific knowledge.22 The long list of what does not work to reduce recidivism includes boot camps, programs that focus on humiliation and punishment, wilderness programs, psychoanalysis, acupuncture, and pet and art programs, many of which are goodwill attempts by private organizations. Latessa, Cullen, and Gendreau point to the principles of effective correctional programs established by the Canadian social psychologist Don A. Andrews, which are now widely quoted in contemporary American criminal justice literature . Andrews acknowledges that” risk factors for criminal conduct may be biological, personal, interpersonal, and/or structural, cultural, political and economic; and may reflect immediate circumstances.”23 (Bruce's, Angel's, and Adam's stories illustrate the complex interaction of some of these risk factors.) Emphasizing the importance of individual differences in criminal behavior, Andrews argues that offenders have to be rigorously assessed to determine their specific criminogenic risk factors and needs. These risks and needs have to be addressed through a cognitive-behavioral approach administered by qualified, warm, genuine, and well-supervised professionals in an environment of integrity. Treatment style, modes, and strategies have to be matched with the learning style of the individual. Cullen and Jonson note that programs that conform to the principles of effective treatment reduce recidivism by 20 to 25 percent. Interestingly, they also stress that the propensity to commit crimes decreases with age.24

Taking these findings one step further, advocates of America's evidence-based rehabilitation movement believe that treatment should not be limited to our nation's prison population, stressing the need for reentry agencies that provide aftercare and early childhood intervention for children at risk.25

One obvious problem with these noble principles and suggestions is that academic findings take time to permeate the spheres of those they target. Although criminologists like Latessa have examined hundreds of service programs for ex-cons and made suggestions on how to improve them, there is still a large fraction of “rehabilitation” programs that work without the existing knowledge of what causes crime and what has to be done to prevent it. Work continues to be seen as both the desired method and result of rehabilitation, despite the fact that it is only marginally linked to recidivism.26 But even if a reentry organization has the best intentions, its positive results may be skewed. In order to prove reduced recidivism rates and gain private and public funding, many organizations “cherry-pick” the most promising ex-offenders, leaving behind those who need their services the most but who may be the least promising in terms of recidivism.

MEASURING SUCCESS

At first glance, considering the hardships facing a majority of ex-offenders, Angel's, Bruce's, and Adam's journeys read like success stories of rehabilitation: each man served his extensive sentence and was released into the Castle, a halfway house with an excellent reputation. The Fortune Society helped them search for work and housing, get medical insurance, and apply for food stamps; as of this writing, all three have managed to stay out of prison. On the surface the system works smoothly and in favor of those who need it the most. But these “ideal” circumstances make Angel, Bruce, and Adam exceptions to the rule. For most ex-cons the transition into the free world looks much bleaker. Fortune’s halfway house offers only sixty beds—not nearly enough to accommodate the tens of thousands of New Yorkers coming home from prison each year. Few of the other halfway houses are as clean and safe, and most offer neither practical nor emotional support. Many ex-cons struggle with addictions and have to spend their days on the street and their nights at unsanitary and unsafe homeless shelters.

But behind Angel’s, Bruce’s, and Adam’s alleged successful rehabilitation unravels a far more complex and untidy story. The men have been “incapacitated” and “deterred” for decades; they have been institutionalized for almost as long as they can remember. The Division of Criminal Justice Services determined their sentences; the Department of Correctional Services decided how and where their sentences were served and what programs they were to attend; religious institutions promised their redemption before God; the Division of Parole dictated their release and determined their curfew and their reappearances before their parole officers and the board. Now the Fortune Society continues this strict regimen, controlling their lives with its various programs, obligations, and daily drug testing. The three men have yet to realize freedom fully.

In the light of all this we have to ask ourselves what effects incapacitation and deterrence, as well as life within an endless chain of institutions and rehabilitation programs, have on the individual. Within this institutional maze, how does the individual balance his or her own needs, fears, and desires? Will he or she ever be allowed to cross over into “our” world? If I interpret Cullen and Jonson’s definition of rehabilitation accurately, these needs, fears, and desires dwell in the “other aspects of an offender’s life,” aspects that, “where possible,” should “also” be improved. Yet I have found little to no information on these “other aspects” and virtually none on the moral dimension of successful rehabilitation. Finding a job, housing, and staying out of prison are certainly important. But what about rehabilitation at heart, an individual’s (lack of) remorse, his or her insights and moral growth? I would argue that true rehabilitation has to do with the willingness and capacity to take responsibility for one’s crime. It is internal. Rehabilitation at heart lies buried beneath statistics, academic principles, and public policy because it is hard to measure and generalize. My book tries to explore this phenomenon with the tools of literary journalism: intimacy and extensive dialogue between journalist and subjects, expository scenes, and an acknowledged subjective view.

Adam, Angel, and Bruce are certainly grateful for Fortune’s help, but they are also dismayed about their newly gained “freedom.” The men were spit out of one system and into another; their old selves were shattered. Forced to reassemble themselves, they began marking time yet again. After decades behind bars, decision making becomes a real problem, and freedom can be outright frightening. What if I hurt someone again? How does one cross the street, use an ATM, or ride the subway? And how do you shop? Intimate relationships are hard to find after being “away” for such a long time. Despite the assumption that they have served their time for committing their crime, suddenly, the men’s criminal past moves once again into the foreground. How does Adam, for example, negotiate his debilitating shame, guilt, and insecurity—those stumbling blocks on his endless road to rehabilitation? How can Bruce carry his burdensome past yet move on? These are just a few, seemingly mundane, yet existential questions that have occupied Bruce, Adam, Angel, and me.

Whereas Bruce and Adam try to deal with their problems internally, Angel deals with his externally. He uses the media (and the media uses him) to help him prove his successful rehabilitation. This book highlights not only the stumbling blocks but also the resources its protagonists find within themselves and in their new world.

Considering their differences in character and coping strategies, it becomes clear why each man’s story—his needs, desires, risks, failures, and moral responsibilities—calls for a highly individualized approach. (In that sense my modus operandi honors Andrews’s emphasis of the individual.) I observed each man trying to figure out his own measure of successful rehabilitation. Angel, Bruce, and Adam had to figure out which forces to fight and which ones to employ on their path.

As the book’s narrative continues, it becomes clear that the only jobs available for people who have spent decades behind bars for murder are the ones offered by reentry agencies themselves, serving the same population the offenders have known—and possibly tried to leave behind—since they were children. Reentry appears to be a microcosm hermetically sealed from the outside world it parallels. This seal is penetrable only when it comes to religious groups. (Not coincidentally, Adam converted to Islam while in prison, and Angel joined the Quakers.) Believing that human beings are created in the image of God, most Christians consider no one beyond redemption. But Adam, Angel, and Bruce move freely only within their religious and reentry communities; beyond those domains genuine integration remains an illusion. By inserting myself into the world of my subjects, by listening and engaging in an intimate—and fearless—dialogue, I am attempting to crack the hermetic seal.

Initially, I thought I would follow Adam, Bruce, and Angel during their first year of freedom and then write my book. But I quickly realized that after twenty or thirty years in prison, these men would require much more than a series of traditional interviews. I didn’t want to listen only to predigested experiences and describe “the approach” of institutions that claim to rehabilitate. My protagonists’ attempts at rehabilitation happened on the subway, at the barbershop, onstage, at the park, at a Halloween party, at work, and over dinner. I wanted to be there when things were happening and ended up shadowing my protagonists for more than two years—from spring 2007 into the summer of 2009. I continued to check in with them periodically in the years that followed. My goal is to provide a visceral sense of their odyssey from prison to freedom. I couldn’t have predicted what their new experiences in the free world entailed—their obstacles, the things that puzzled them about “our” world, what delighted them, what scared them, and, perhaps most surprising, what they missed about prison.

Among Murderers examines through my own personal viewpoint the pariah status of three men who have been convicted of society’s most heinous crimes and who have returned to the free world. Although I rely on interviews, parole and court documents, hospital reports, and letters to tell the men’s stories, I also admit to my personal struggles in coming to terms with their complex characters and crimes. I have immersed myself in their world, hoping to create an entrance to solving a conflict that has long been neglected. By giving a voice to three individuals, marginalized from society by their crimes and prison sentences, and by exploring their discomfiting, jarring realities, I hope to illuminate a much-neglected epidemic.

Naturally, it is not only their narrative anymore; it has also become mine. More important, though, their stories point to our society at large. For the longest time we have tried to hide from view this significant part of our population. Now that these former criminals are returning to our society, we need to redefine our stance. Do we allow for the reintegration of murderers, assailants, robbers, and rapists, men and women who have been convicted of dreadful crimes? What do we need to take into consideration as we craft policies that seek to reform and redeem former prisoners—and ourselves? I believe that the most trivial details can expose the most complex psychological circumstances and mysteries of human life. By featuring my observations, conversations, and boundary points, I hope to open up an honest dialogue about crime, rehabilitation, and reentry.