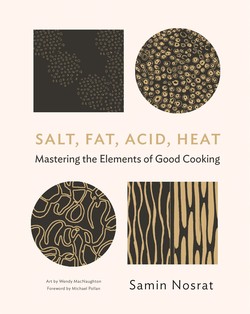

Читать книгу Salt, Fat, Acid, Heat - Samin Nosrat - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеGrowing up, I thought salt belonged in a shaker at the table, and nowhere else. I never added it to food, or saw Maman add it to food. When my aunt Ziba, who had a well-documented taste for salt, sprinkled it onto her saffron rice at the table each night, my brothers and I giggled. We thought it was the strangest, funniest thing in the world. “What on earth,” I wondered, “can salt do for food?”

I associated salt with the beach, where I spent my childhood seasoned with it. There were the endless hours in the Pacific, swallowing mouthful after mouthful of ocean water when I misjudged the waves. Tidepooling at twilight, my friends and I often fell victim to the saltwater spray while we poked at anemones. And my brothers, chasing me on the sand with giant kelp, would tickle and taunt me with its salty, otherworldly tassels whenever they caught up to me.

Maman always kept our swimsuits in the back of our blue Volvo station wagon, because the beach was always where we wanted to be. She was deft with the umbrella and blankets, setting them up while she shooed the three of us into the sea.

We’d stay in the water until we were starving, scanning the beach for the sun-faded coral-and-white umbrella, the only landmark that would lead us back to Maman. Wiping saltwater from our eyes, we beelined to her.

Somehow, Maman always knew exactly what would taste best when we emerged: Persian cucumbers topped with sheep’s milk feta cheese rolled together in lavash bread. We chased the sandwiches with handfuls of ice-cold grapes or wedges of watermelon to quench our thirst.

That snack, eaten while my curls dripped with seawater and salt crust formed on my skin, always tasted so good. Without a doubt, the pleasures of the beach added to the magic of the experience, but it wasn’t until many years later, working at Chez Panisse, that I understood why those bites had been so perfect from a culinary point of view.

While waiting tables during the first year I worked at Chez Panisse, the closest I usually got to the food was at tasters, when the cooks made each dish for the chef to critique before service. With a menu that changed daily, the chef needed tasters to ensure that his or her vision was realised. Everything had to be just right. The cooks would tinker and adjust until satisfied; then they’d hand over the dishes to the floor staff to taste. On the tiny back porch, a dozen of us would hover over the plates, passing them around until we’d all had a bite of everything. It was there that I first tasted crisp deep-fried quail, tender salmon grilled in a fig leaf, and buttermilk panna cotta with fragrant wild strawberries. Often, the powerful flavours would haunt me throughout my shift.

Once I developed culinary aspirations, Chris Lee, the chef who’d eventually take me under his wing, suggested that I pay less attention to what was happening on the porch during tasters, and more to what was happening in the kitchen. The language the chefs used, how they knew when something was right—these were clues about how to become a better cook. Most often, when a dish fell flat, the answer lay in adjusting the salt. Sometimes it was in the form of salt crystals, but other times it meant a grating of cheese, some pounded anchovies, a few olives, or a sprinkling of capers. I began to see that there is no better guide in the kitchen than thoughtful tasting, and that nothing is more important to taste thoughtfully for than salt.

One day the following year, as a young cook in the prep kitchen, I was tasked with cooking polenta. I’d tasted polenta only once before coming to Chez Panisse, and I wasn’t a fan. Precooked and wrapped in plastic like a roll of cookie dough, it was flavourless. But I’d promised myself that I would try everything at the restaurant at least once, and when I tasted polenta for the second time, I couldn’t believe that something so creamy and complex could share a name with that flavourless tube of astronaut food. Milled from an heirloom variety of corn, each bite of the polenta at Chez Panisse tasted of sweetness and earth. I couldn’t wait to cook some myself.

Once the chef, Cal Peternell, talked me through the steps of making the polenta, I began cooking. Consumed by the fear of scorching and ruining the entire humongous pot—a mistake I had seen other cooks make—I stirred maniacally.

After an hour and a half, I’d added in butter and Parmesan, just as Cal had instructed me. I brought him a spoonful of the creamy porridge to taste. At six foot four, Cal is a gentle giant with sandy-blond hair and the driest of wits. I looked expectantly up at him with equal parts respect and terror. He said, in his signature deadpan, “It needs more salt.” Dutifully, I returned to the pot and sprinkled in a few grains of salt, treating them with the preciousness I might afford, say, gold leaf. I thought it tasted pretty good, so I returned to Cal with a spoonful of my newly adjusted polenta.

Again, a moment’s consideration was all he needed to know the seasoning was off. But now—to save himself the trouble and time, I imagine—he marched me back to the pot and added not one but three enormous palmfuls of kosher salt.

The perfectionist in me was horrified. I had wanted so badly to do that polenta justice! The degree to which I’d been off was exponential. Three palmfuls!

Cal grabbed spoons and together we tasted. Some indescribable transformation had occurred. The corn was somehow sweeter, the butter richer. All of the flavours were more pronounced. I’d been certain Cal had ruined the pot and turned my polenta into a salt lick, but no matter how I tried, the word salty did not apply to what I tasted. All I felt was a satisfying zing! with each mouthful.

It was as if I’d been struck by lightning. It’d never occurred to me that salt was anything more than pepper’s sidekick. But now, having experienced the transformative power of salt for myself, I wanted to learn how to get that zing! every time I cooked. I thought about all of the foods I’d loved to eat growing up—and that bite of seaside cucumber and feta, in particular. I realised then why it had tasted so good. It was properly seasoned, with salt.

WHAT IS SALT?

The secret behind that zing! can be explained by some basic chemistry. Salt is a mineral: sodium chloride. It’s one of several dozen essential nutrients without which we cannot survive. The human body can’t store much salt, so we need to consume it regularly in order to be able to carry out basic biological processes, such as maintaining proper blood pressure and water distribution in the body, delivering nutrients to and from cells, nerve transmission, and muscle movement. In fact, we’re hardwired to crave salt to ensure we get enough of it. The lucky consequence of this is that salt makes almost everything taste better to us, so it’s hardly a chore to add it to our food. In fact, by enhancing flavour, salt increases the pleasure we experience as we eat.

All salt comes from the ocean, be it the Atlantic or a long-forgotten sea like the giant prehistoric Lake Minchin of Bolivia, home of the earth’s largest salt flat. Salt that is left behind when seawater evaporates is sea salt, whereas rock salt is mined from ancient lakes and seas, some of which now lie far underground.

The primary role that salt plays in cooking is to amplify flavour. Though salt also affects texture and helps modify other flavours, nearly every decision you’ll make about salt will involve enhancing and deepening flavour.

Does this mean you should simply use more salt? No. It means use salt better. Add it in the right amount, at the right time, in the right form. A smaller amount of salt applied while cooking will often do more to improve flavour than a larger amount added at the table. And unless you have been specifically told by your doctor to limit your salt consumption, you can relax about your sodium intake from homecooked food. When students balk at the palmfuls of salt I add to pots of water for boiling vegetables, I gently point out that most of the salt will end up going down the drain with the cooking water. In almost every case, anything you cook for yourself at home is more nutritious, and lower in sodium, than processed, prepared, or restaurant food.

SALT AND FLAVOUR

James Beard, the father of modern American cookery, once asked, “Where would we be without salt?” I know the answer: adrift in a sea of blandness. If only one lesson from this book stays with you, let it be this: Salt has a greater impact on flavour than any other ingredient. Learn to use it well, and your food will taste good.

Salt’s relationship to flavour is multidimensional: it has its own particular taste, and it enhances the flavour of other ingredients. Used properly, salt minimises bitterness, balances out sweetness, and enhances aromas, heightening our experience of eating. Imagine taking a bite of a rich espresso brownie sprinkled with flaky sea salt. Besides providing the delightful experience of its delicate flakes crunching on the tongue, the salt minimises the espresso’s bitterness, intensifies the flavour of the chocolate, and offers a welcome savoury contrast to the sugar’s sweetness.

The Flavour of Salt

Salt should taste clean, free of any unpleasant flavours. Start by tasting it all on its own. Dip your finger into your salt cellar and let a few grains dissolve on your tongue. What do they taste like? Hopefully like the summer sea.

Types of Salt

Chefs all have their saline allegiances and will offer lengthy, impassioned arguments about why one variety of salt is superior to another. But honestly, what matters most is that you’re familiar with whichever salt you use. Is it coarse or fine? How long does it take to dissolve in a pot of boiling water? How much does it take to make a roast chicken taste just right? If you add your salt to a batch of cookie dough, will it melt away or make itself known, announcing its presence with a pleasant crunch?

Though all salt crystals are produced by evaporating water from saltwater brine, the pace of evaporation will determine the shape those crystals take. Rock salts are mined by flooding salt deposits with water and then rapidly evaporating that water from the resulting brine. Refined sea salt is similarly produced through the rapid evaporation of seawater. When formed as a result of rapid evaporation in a closed container, salt crystals become small, dense cubes—granular salt. On the other hand, salt produced slowly through solar methods at the surface of an open container will crystallise into light, hollow flakes. If water splashes into the hollow of the flake before it’s scooped off the surface, it will sink into the brine and transform into a large, dense crystal. This is unrefined, or minimally processed, sea salt.

These varying shapes and sizes can make a big difference in your cooking. A tablespoon of fine salt will pack more tightly, and can be two or three times “saltier” than a tablespoon of coarser salt. This is why it makes sense to measure salts by weight rather than by volume. Better yet, learn to salt to taste.

Table Salt

Common table salt, or granular salt, is found in salt shakers everywhere. Shake some out into your palm and its distinct cubic shape—the result of crystallising in a closed vacuum chamber—will be apparent. Table salt is small and dense, making it very salty. Unless otherwise noted, iodine has been added to it.

I don’t recommend using iodised salt as it makes everything taste slightly metallic. In 1924, when iodine deficiency was a common health problem, Morton Salt began iodising salt to help prevent goitres, leading to great strides in public health. These days, we can get sufficient amounts of iodine from natural sources. As long as your diet is diverse and full of iodine-rich foods such as seafood and dairy, there’s no need to suffer through metallic-tasting food.

Table salt also often contains anticaking agents to prevent clumps from forming, or dextrose, a form of sugar, to stabilise the iodine. Though neither of these additives is harmful, there’s no reason to add them to your food. The only thing you should be adding to your food when you’re salting it is salt! This is one of the few times I’ll insist on anything in this book: if you’ve got only table salt at home, go get yourself some kosher or sea salt right away.

Kosher Salt

Kosher salt is traditionally used in koshering, the traditional Jewish process by which blood is removed from meat. Since kosher salt contains no additives, it tastes very pure. There are two major producers of kosher salt: Diamond Crystal, which crystallises in an open container of brine, yielding light and hollow flakes; and Morton’s, which is made by rolling cubic crystals of vacuum-evaporated salt into thin, dense flakes. The difference in production methods yields two vastly different salts. While Diamond Crystal readily adheres to foods and crumbles easily, Morton’s is much denser, and almost twice as salty by volume. When following recipes requiring kosher salt, make sure to use the specified brand because these two salts are not interchangable! For this book, I tested all the recipes with Diamond Crystal, which comes in a red box and is widely available online but sea salt can be used as an alternative.

Diamond Crystal dissolves about twice as quickly as denser granulated salt, making it ideal for use in food that is cooked quickly. The more quickly salt dissolves, the less likely you are to overseason a dish, thinking it needs more salt when actually the salt just needs more time to dissolve. Because of its increased surface area, Diamond Crystal also sticks to foods better, rather than rebounding or falling off.

Inexpensive and rather forgiving, kosher salt is fantastic for everyday cooking. I prefer Diamond Crystal—even when I’ve accidentally salted dishes twice with this salt while enjoying a little too much my conversation, the company, or a glass of wine, the food has emerged unscathed.

Sea Salt

Sea salt is what’s left behind when seawater evaporates. Natural sea salts such as fleur de sel, sel gris, and Maldon are the less-refined result of gradual, monitored evaporation that can take up to five years. Taking the shape of delicate, distinctly aromatic flakes, fleur de sel—literally, “flower of salt”—is harvested from the surface of special sea salt beds in western France. When it falls below the surface of the water and attracts various sea minerals, including magnesium chloride and calcium sulphate, pure white fleur de sel takes on a greyish hue and becomes sel gris, or grey salt. Maldon salt crystals, formed much like fleur de sel, take on a hollow pyramid shape, and are often referred to as flaky salt.

Because natural salts are harvested using low-yield, labour-intensive methods, they tend to be more expensive than refined sea salts. Most of what you’re paying for when you buy these salts is their delightful texture, so use them in ways that allow them to stand out. It’s a waste to season pasta water with fleur de sel or make tomato sauce with Maldon salt. Instead, sprinkle these salts atop delicate garden lettuces, rich caramel sauces, and chocolate chip cookies as they go into the oven so you can enjoy the way they crunch in your mouth.

The refined granular sea salt you might find at the grocery store is a bit different: it was produced by rapidly boiling down ocean water in a closed vacuum. Fine or medium-size crystals of this type are ideal for everyday cooking. Use this type of sea salt to season foods from within—in water for boiling vegetables or pasta, on roasts and stew meats, tossed with vegetables, and in doughs or batters.

Keep two kinds of salt on hand: an inexpensive one such as sea salt or kosher salt for everyday cooking, and a special salt with a pleasant texture, such as Maldon salt or fleur de sel, for garnishing food at the last moment. Whichever salts you use, become familiar with them—with how salty they are, and how they taste, feel, and affect the flavour of the foods to which you add them.

Salt’s Effect on Flavour

To understand how salt affects flavour, we must first understand what flavour is. Our taste buds can perceive five tastes: saltiness, sourness, bitterness, sweetness, and umami, or savouriness. On the other hand, aroma involves our noses sensing any of thousands of various chemical compounds. The descriptive words often used to characterise the way a wine smells, such as earthy, fruity, and floral, refer to aroma compounds.

Flavour lies at the intersection of taste, aroma, and sensory elements including texture, sound, appearance, and temperature. Since aroma is a crucial element of flavour, the more aromas you perceive, the more vibrant your eating experience will be. This is why you take less pleasure in eating while you’re congested or have a cold.

Remarkably, salt affects both taste and flavour. Our taste buds can discern whether or not salt is present, and in what amount. But salt also unlocks many aromatic compounds in foods, making them more readily available as we eat. The simplest way to experience this is to taste an unsalted soup or broth. Try it next time you make Chicken Stock. The unseasoned broth will taste flat, but as you add salt, you’ll detect new aromas that were previously unavailable. Keep salting, and tasting, and you’ll start to sense the salt as well as more complex and delightful flavours: the savouriness of the chicken, the richness of the chicken fat, the earthiness of the celery and the thyme. Keep adding salt, and tasting, until you get that zing! This is how you’ll learn to salt “to taste.” When a recipe says “season to taste,” add enough salt until it tastes right to you.

This flavour “unlocking” is also one reason why professional cooks like to season sliced tomatoes a few minutes before serving them—so that, as salt helps the flavour molecules that are bound up within the tomato proteins, each bite will taste more intensely of tomato.

Salt also reduces our perception of bitterness, with the secondary effect of emphasising other flavours present in bitter dishes. Salt enhances sweetness while reducing bitterness in foods that are both bitter and sweet, such as bittersweet chocolate, coffee ice cream, or burnt caramels.

Though we typically turn to sugar to balance out bitter flavours in a sauce or soup, it turns out that salt masks bitterness much more effectively than sugar. See for yourself with a little tonic water, Campari, or grapefruit juice, all of which are both bitter and sweet. Taste a spoonful, then add a pinch of salt and taste again. You’ll be surprised by how much bitterness subsides.

Seasoning

Anything that heightens flavour is a seasoning, but the term generally refers to salt since it’s the most powerful flavour enhancer and modifier. If food isn’t salted properly, no amount of fancy cooking techniques or garnishes will make up for it. Without salt, unpleasant tastes are more perceptible and pleasant ones less so. Though in general the absence of salt in food is deeply regrettable, its overt presence is equally unwelcome: food shouldn’t be salty, it should be salted.

Salting isn’t something to do once and then check off your list; be constantly aware of how a dish tastes as it cooks, and how you want it to taste at the table. At San Francisco’s legendary Zuni Café, chef Judy Rodgers often told her cooks that a dish might need “seven more grains of salt.” Sometimes it really is that subtle; just seven grains can mean the difference between satisfactory and sublime. Other times, your polenta might require a handful. The only way to know is to taste and adjust.

Tasting and adjusting—over and over again as you add ingredients and they transform throughout the cooking process—will yield the most flavourful food. Getting the seasoning right is about getting it right at every level—bite, component, dish, and meal. This is seasoning food from within.

On the global spectrum of salt use, there’s a range, rather than a single point, of proper seasoning. Some cultures use less salt; others use more. Tuscans don’t add salt to their bread but more than make up for it with the copious handfuls they add to everything else. The French salt baguettes and pain au levain perfectly, in turn seasoning everything else a little more conservatively.

In Japan, steamed rice is left unseasoned to act as the foil for the flavourful fishes, meats, curries, and pickles served alongside it. In India, biryani, a flavourful rice dish layered with vegetables, meat, spices, and eggs, is never left unsalted. There is no universal rule other than that salt use must be carefully considered at every point in the cooking process. This is seasoning to taste.

When food tastes flat, the most common culprit is underseasoning. If you’re not sure salt will fix the problem, take a spoonful or small bite and sprinkle it with a little salt, then taste again. If something shifts and you sense the zing!, then go ahead and add salt to the entire batch. Your palate will become more discerning with this sort of thoughtful cooking and tasting. Like a jazz musician’s ear, with use it will grow more sensitive, more refined, and more skilled at improvisation.

HOW SALT WORKS

Cooking is part artistry, part chemistry. Understanding how salt works will allow you to make better decisions about how and when to use it to improve texture and season food from within. Some ingredients and cooking methods require giving salt enough time to penetrate food and distribute itself within it. In other cases, the key is to create a cooking environment salty enough to allow food to absorb the right amount of salt as it cooks.

The distribution of salt throughout food can be explained by osmosis and diffusion, two chemical processes powered by nature’s tendency to seek equilibrium, or the balanced concentration of solutes such as minerals and sugars on either side of a semipermeable membrane (or holey cell wall). In food, the movement of water across a cell wall from the less salty side to the saltier side is called osmosis.

Diffusion, on the other hand, is the often slower process of salt moving from a saltier environment to a less salty one until it’s evenly distributed throughout. Sprinkle salt on the surface of a piece of chicken and come back twenty minutes later. The distinct grains will no longer be visible: they will have started to dissolve, and the salt will have begun to move inward in an effort to create a chemical balance throughout the piece of meat. We can taste the consequence of this diffusion—though we sprinkle salt on the surface of the meat, with the distribution that occurs over time, eventually the meat will taste evenly seasoned, rather than being salty on the surface and bland within.

Water will also be visible on the surface of the chicken, the result of osmosis. While the salt moves in, the water will move out with the same goal: achieving chemical balance throughout the entire piece of meat.

Given the chance, salt will always distribute itself evenly to season food from within, but it affects the textures of different foods in different ways.

How Salt Affects . . .

Meat

By the time I arrived at Chez Panisse, the kitchen had already been running like a well-oiled machine for decades. Its success relied on each cook thinking ahead to the following day’s menu and beyond. Every day, without fail, we butchered and seasoned meat for the following day. Since this task was a classic example of kitchen efficiency, it didn’t occur to me that seasoning the meat in advance had anything to do with flavour. That was only because I didn’t yet understand the important work salt was quietly doing overnight.

Since diffusion is a slow process, seasoning in advance gives salt plenty of time to diffuse evenly throughout meat. This is how to season meat from within. A small amount of salt applied in advance will make a much bigger difference than a larger amount applied just before serving. In other words, time, not amount, is the crucial variable.

Because salt also initiates osmosis, and visibly draws water out of nearly any ingredient it touches, many people believe that salt dries and toughens food. But with time, salt will dissolve protein strands into a gel, allowing them to absorb and retain water better as they cook. Water is moisture: its presence makes meat tender and juicy.

Think of a protein strand as a loose coil with water molecules bound to its outside surface. When an unseasoned protein is heated, it denatures: the coil tightens, squeezing water molecules out of the protein matrix, leaving the meat dry and tough if overcooked. By disrupting protein structure, salt prevents the coil from densely coagulating, or clumping, when heated, so more of the water molecules remain bound. The piece of meat remains moister, and you have a greater margin of error for overcooking.

This same chemical process is the secret to brining, the method in which a piece of meat is submerged in a bath of water spiked with salt, sugar, and spices. The salt in this mixture, or brine, dissolves some of the proteins, while the sugar and spices offer plenty of aromatic molecules for the meat to absorb. For this reason, brining can be a great strategy for lean meats and poultry, which tend to be dry and even bland. Make Spicy Brined Turkey Breast, and you’ll see how a night spent in a salty, spicy bath will transform a cut of meat that’s often devastatingly dry and flavourless.

I can’t remember the first time I tasted—consciously, anyway—meat that had been salted in advance. But now I can tell every time I taste meat that hasn’t. I’ve cooked thousands of chickens—presalted and not—over the years, and while science has yet to confirm my suspicions, I’ll speak from experience here: meat that’s been salted in advance is not only more flavourful, it’s also more tender, than meat that hasn’t. The best way to experience the marvels of preseasoned meat for yourself is with a little experiment: the next time you plan to roast a chicken, cut the bird in half, or ask your butcher to do so for you. Season one half with salt a day ahead. Season the other half just before cooking. The effects of early salting will be apparent long before the first bite hits your tongue. The chicken salted in advance will fall off the bone as you begin to butcher it, while the other half, though moist, won’t begin to compare in tenderness.

When salting meat for cooking, any time is better than none, and more is better than some. Aim to season meat the day before cooking when possible. Failing that, do it in the morning, or even in the afternoon. Or make it the first thing you do when collecting ingredients for dinner. I like to do it as soon as I get home from the grocery store, so I don’t have to think about it again.

The larger, denser, or more sinewy the piece of meat, the earlier you should salt it. Oxtails, shanks, and short ribs can be seasoned a day or two in advance to allow salt time to do its work. A chicken for roasting can be salted the day before cooking, while Thanksgiving turkey should be seasoned two, or even three, days in advance. The colder the meat and surrounding environment are, the longer it will take the salt to do its work, so when time is limited, leave meat on the worktop once you season it (but for no longer than two hours), rather than returning it to the fridge.

Though salting early is a great boon to flavour and texture in meat, there is such a thing as salting too early. For thousands of years, salt has been used to preserve meat. In large enough quantities, for long enough periods of time, salt will dehydrate meat and cure it. If dinner plans change at the last minute, a salted chicken or a few pounds of short ribs will happily wait a day or two to be roasted or braised. But wait much longer than that, and they will dry out and develop a leathery texture and a cured, rather than fresh, flavour. If you’ve salted some meat but realise you won’t be able to get to it for several days, freeze it until you’re ready to cook it. Tightly wrapped, it’ll keep for up to two months. Simply defrost and pick up cooking where you left off.

Seafood

Unlike meat, the delicate proteins of most fish and shellfish will degrade when salted too early, yielding a tough, dry, or chewy result. A brief salting—about fifteen minutes—is plenty to enhance flavour and maintain moisture in flaky fish. 2.5cm -thick steaks of meatier fish, such as tuna and swordfish, can be salted up to thirty minutes ahead. Season all other seafood at the time of cooking to preserve textural integrity.

Fat

Salt requires water to dissolve, so it won’t dissolve in pure fat. Luckily, most of the fats we use in the kitchen contain at least a little water—the small amounts of water in butter, lemon juice in a mayonnaise, or vinegar in a vinaigrette allow salt to slowly dissolve. Season these fats early and carefully, waiting for salt to dissolve and tasting before adding more. Or, dissolve salt in water, vinegar, or lemon juice before adding it to fat for even, immediate distribution. Lean meat has a slightly higher water (and protein) content—and thus, greater capacity for salt absorption—than fattier cuts of meat, so cuts with a big fat cap, such as pork loin or rib eye, will not absorb salt evenly. This is illustrated beautifully in a slice of prosciutto: the lean muscle (rosy pink part) has a higher water content, and thus can absorb salt readily as it cures. The fat (pure white part), on the other hand, has a much lower water content, and so it doesn’t absorb salt at the same rate. Taste the two parts separately and you’ll find the lean muscle unpleasantly salty. The strip of fat will seem almost bland. But taste them together and the synergy of fat and salt will be revealed. Don’t let this absorption imbalance affect how you season a fatty cut. Simply taste both fat and lean meat before adding more salt at the table.

Eggs

Eggs absorb salt easily. As they do, it helps their proteins come together at a lower temperature, which decreases cooking time. The more quickly the proteins set, the less of a chance they will have to expel water they contain. The more water the eggs retain as they cook, the more moist and tender their final texture will be. Add a pinch of salt to eggs destined for scrambling, omelettes, custards, or frittatas before cooking. Lightly season water for poaching eggs. Season eggs cooked in the shell or fried in a pan just before serving.

Vegetables, Fruits, and Fungi

Most vegetables and fruit cells contain an undigestible carbohydrate called pectin. Soften the pectin through ripening or applying heat, and you will soften the fruit or vegetable, making it more tender, and often more delicious, to eat. Salt assists in weakening pectin.

When in doubt, salt vegetables before you cook them. Toss vegetables with salt and olive oil for roasting. Salt blanching water generously before adding vegetables. Add salt into the pan along with the vegetables for sautéing. Season vegetables with large, watery cells—tomatoes, courgettes, and aubergines, for example—in advance of grilling or roasting to allow salt the time to do its work. During this time, osmosis will also cause some water loss, so pat the vegetables dry before cooking. Because salt will continue to draw water out of vegetables and fruits and eventually make them rubbery, be wary of salting them too early—usually 15 minutes before cooking is sufficient.

While mushrooms don’t contain pectin, they are about 80 percent water, which they will begin to release when salted. In order to preserve the texture of mushrooms, wait to add salt until they’ve just begun to brown in the pan.

Legumes and Grains

Tough beans: a kitchen fiasco so common it’s become an idiom. If there’s one way to permanently turn people off of legumes, it’s serving them undercooked, bland beans that are hard to eat. Contrary to popular belief, salt does not toughen dried beans. In fact, by facilitating the weakening of pectins contained in their cell walls, salt affects beans in the same way it affects vegetables: it softens them. In order to flavour dried beans from within, add salt when you soak them or when you begin to cook them, whichever comes first.

Legumes and grains are dried seeds—the parts of a plant that ensure survival from one season to the next. They’ve evolved tough exterior shells for protection, and require long, gentle cooking in water to absorb enough water to become tender. The most common reason for tough beans and grains, then, is undercooking. The solution for most: keep simmering! (Other variables that can lead to tough beans include using old or improperly stored beans, cooking with hard water, and acidic conditions.) Since a long cooking time gives salt a chance to diffuse evenly throughout, the water for boiling grains such as rice, farro, or quinoa can be salted less aggressively than the water for blanching vegetables. In preparations where all of the cooking water will be absorbed, and hence all of the salt, be particularly careful not to overseason.

Doughs and Batters

The first paid job I had in the kitchen at Chez Panisse was called Pasta/Lettuce. I spent about a year washing lettuces and making every kind of pasta dough imaginable. I’d also start the pizza dough every morning, adding yeast, water, and flour into the bowl of the gigantic stand mixer and tending to it throughout the day. Once the water and flour brought the dormant yeast back to life, I’d add more flour and salt. Then, after kneading and proofing, I’d finish the dough by adding in some olive oil. One day, when it was time to add the flour and salt, I realised the salt bin was empty. I didn’t have the time right then to go down to the storage shed to get another bag of salt, so I figured I’d just wait to add the salt at the end, along with the oil. As I kneaded the dough, I noticed that it came together much more quickly than usual, but I didn’t really give it a second thought. When I returned a couple of hours later to finish the dough, something unbelievable happened. I turned on the machine and let it deflate and knead the dough, like I always did, and then I added the salt. As it dissolved into the dough, I could actually see the machine begin to strain. The salt was making the dough tougher—the difference was remarkable! I had no idea what was happening. I was worried that I’d done something terribly wrong.

It was no big deal. It turns out that the dough tightened immediately because salt aids in strengthening gluten, the protein that makes dough chewy and elastic. As soon as I allowed the dough to rest, the gluten relaxed, and the pizzas that night emerged from the oven as delicious as always.

Salt can take a while to dissolve in foods that are low in water, so add it to bread dough early. Leave it out of Italian pasta dough altogether, allowing the salted water to do the work of seasoning as it cooks. Add it early to ramen and udon doughs to strengthen their gluten, as this will result in the desired chewiness. Add salt later to batters and doughs for cakes, pancakes, and delicate pastries to keep them tender, but make sure to whisk these mixes thoroughly so that the salt is evenly distributed before cooking.

Cooking Foods in Salted Water

Properly seasoned cooking water encourages food to retain its nutrients. Imagine that you’re cooking green beans in a pot of water. If the water is unseasoned or only lightly seasoned, then its concentration of salt—a mineral—will be lower than the innate mineral concentration in the green beans. In an attempt to establish equilibrium between the internal environment of the green beans and the external environment of the cooking water, the beans will relinquish some of their minerals and natural sugars during the cooking process. This leads to bland, grey, less-nutritious green beans.

On the other hand, if the water is more highly seasoned—and more mineral rich— than the green beans, then the opposite will happen. In an attempt to reach equilibrium, the green beans will absorb some salt from the water as they cook, seasoning themselves from the inside out. They’ll also remain more vibrantly coloured because the salt balance will keep magnesium in the beans’ chlorophyll molecules from leaching out. The salt will also weaken the pectin and soften the beans’ cell walls, allowing them to cook more quickly. As an added bonus, there will be less of an opportunity for the green beans to lose nutrients because they’ll spend less total time in the pot.

I can’t prescribe precise amounts of salt for blanching water for a few reasons: I don’t know what size your pot is, how much water you’re using, how much food you’re blanching, or what type of salt you’re using. All of these variables will dictate how much salt to use, and even they may change each time you cook. Instead, season your cooking water until it’s as salty as the sea (or more accurately, your memory of the sea. At 3.5 percent salinity, seawater is much, much saltier than anyone would ever want to use for cooking). You might flinch upon seeing just how much salt this takes, but remember, most of the salt ends up going down the drain. The goal is to create a salty enough environment to allow the salt to diffuse throughout the ingredient during the time it spends in the water.

It doesn’t matter whether you add the salt to the water before or after you set it on the heat, though it’ll dissolve, and hence diffuse, faster in hot water. Just make sure to give the salt a chance to dissolve, and taste the water to make sure it’s highly seasoned before you add any food. Keep a pot boiling on the stove for too long, though, and water will evaporate. What’s left behind will be far too salty for cooking. The cure here is simple: taste your water, and make sure it’s right. If not, add some water or salt to balance it out.

Cooking food in salted water is one of the simplest ways to season from within. Taste roasted potatoes that were seasoned with salt as they went into the oven, and you’ll taste salt on the surface but not much farther in. But taste potatoes that were simmered in salted water for a little while before being roasted, and you’ll be shocked by the difference—salt will have made it all the way into the centre, doing its powerful work of seasoning from within along the way.

Salt pasta water, potato cooking water, and pots of grains and legumes as early as possible to allow salt to dissolve and diffuse evenly into the food. Season the water for vegetables correctly and you won’t have to add salt again before serving. Salads made with boiled vegetables—be it potatoes, asparagus, cauliflower, green beans, or anything else—are most delicious when the vegetables are seasoned properly while they’re cooking. Salt sprinkled on top of one of these salads at the time of serving won’t make as much of a difference in flavour as it will in texture, by adding a pleasant crunch.

Salt meats that are going to be cooked in water, like any meats, in advance, but season the cooking liquids for stews, braises, and poached meats conservatively—keep in mind that you’ll be consuming any salt you add here. While some salt may leach from the seasoned meat into the less savoury broth, it will have already done its important tenderising work. Anticipate the flavour exchange that will happen between the seasoned meat and its cooking liquid, and taste and adjust the liquid, along with the meat, before serving.

Read on to learn more about the nuances of blanching, braising, simmering, and poaching, in Heat.

DIFFUSION CALCULUS

The three most valuable tools to encourage salt diffusion are time, temperature, and water. Before setting out to cook—as you choose an ingredient, or a cooking method— ask yourself, “How can I season this from within?” Then, use these variables to plot out how far in advance—and how much—to salt your food or cooking water.

Time

Salt is very slow to diffuse. If you are cooking something big or dense and want to get salt into it, season the ingredient as early as possible to give salt the time to travel to the centre.

Temperature

Heat stimulates salt diffusion. Salt will always diffuse more quickly at room temperature than in the fridge. Use this fact to your advantage when you’ve forgotten to salt your chicken or steak in advance. Pull the meat out of the fridge when you get home, salt it, and let it sit out while the oven or grill preheats.

Water

Water promotes salt diffusion. Use watery cooking methods to help salt penetrate dense, dry, and tough ingredients, especially if you don’t have time to season them in advance.

USING SALT

The British food writer Elizabeth David once said, “I do not even bother with a salt spoon. I am not able to see what is unmannerly or wrong with putting one’s fingers into the salt.” I agree. Get rid of the shaker, dump the salt in a bowl, and start using your fingers to season your food. You should be able to fit all five fingers into your salt bowl and easily grab a palmful of salt. This important—but often unsaid—rule of good cooking is so routine for professional cooks that when working in an unfamiliar kitchen, we instinctively hunt for containers to use as salt bowls. When pressed, I’ve even used coconut shells to hold salt. I once taught a class at the national cooking school in Cuba: the state-run kitchen was so barren that I ended up sawing plastic water bottles in half to use for holding salt and other garnishes. It got the job done.

Measuring Salt

Abandoning precise measurements when using salt requires an initial leap of faith. When I was first learning how to cook, I always wondered how I’d know when I’d added enough. I wondered how I’d avoid using way too much. It was discombobulating. And the only way to know how much salt to use was to add it incrementally and taste with each addition. I had to get to know my salt. With time, I learned that a huge pot of pasta water required three handfuls to start. I figured out that when I seasoned chickens for the spit, it should look like a light snowstorm had fallen over the butchering table. It was only with repetition and practice that I found these landmarks. I also found a few exceptions: certain pastry, brine, and sausage recipes where all of the ingredients are precisely weighed out don’t need constant adjusting. But I still salt every other thing I cook to taste.

The next time you’re seasoning a pork loin for roasting, pay attention to how much you use, and then take a moment when you take your first bite to consider if you got the seasoning right. If so, commit to memory the way the salt looked on the surface of the meat. If not, make a mental note to increase or decrease the amount of salt next time. You already possess the very best tool for evaluating how much salt to use—a tongue. Conditions in the kitchen are rarely, if ever, identical twice. Since we don’t use the same pot every time, or the same amount of water, the same size chicken or number of carrots, measurements can be tricky. Instead, rely on your tongue, and taste at every point along the way. With time, you’ll learn to use other senses to gauge how much salt to use—touch, sight, and common sense can be just as important as taste. The late, great Marcella Hazan, who authored the indispensable Essentials of Classic Italian Cooking, could tell when a dish needed more salt by simply smelling it!

My general ratios for measuring salt are simple: 1 percent salt by weight for meats, vegetables, and grains, and 2 percent salinity for water for blanching vegetables and pasta. To see what these numbers translate to by volume for various salts, take a look at the chart on the next page. If using the amounts of salt I prescribe terrifies you, try a little experiment: set up two pots of water, and season one as you normally would. Season the other to 2 percent salinity, and note what it feels and looks like to use that much salt. Cook half of your green beans, broccoli, asparagus, or pasta in each pot of water, and compare the flavour when you eat them. I suspect the taste test will be enough to convince you to trust me.

Consider these ratios a starting point. Soon—maybe just after one or two pots of pasta—you’ll be able to judge how much salt is enough by trusting the way the grains feel as they fall from your palm and whether or not, upon tasting, you’re transported to the sea.

How to Salt

Once you realise how much salt it takes to season something properly, you might start to believe there’s no such thing as too much. This happened to me. I remember when a chef I particularly admired walked into the downstairs butchery room where I’d been sent to season pork roasts for the following night’s dinner. Having recently come to appreciate the power of salt, I decided that in order to cover the roasts evenly, I’d roll them in a huge bowl of salt to ensure that every surface was adequately coated. As she came down the stairs, her eyebrows shot up. I’d been using enough salt to cure the roasts for three years! They’d be completely inedible the next night. I spent the next twenty minutes rinsing the salt off the meat. Later, the chef showed me the proper hand grasp for distributing salt evenly on large surfaces.

I didn’t understand the nuances of the act of salting until I began paying attention to the various ways cooks used salt in different situations. There was the way we salted pots of water for blanching vegetables or pasta with near abandon, adding palmful after palmful, only to await its dissolution, lightly skimming a finger across the rolling boil, tasting thoughtfully, and more often than not, adding even more.

There was the way we seasoned trays of vegetables, lined up duck legs butchered for confit, even larger cuts of meat, and pans of focaccia ready for the oven. This was done by lightly grasping the salt in your upturned palm, letting it shower down with a wag of the wrist. This grasp—not the hovering pinch I was used to—was the way to distribute salt, flour, or anything else granular, evenly and efficiently over a large surface.

Practise the wrist wag in your own kitchen over a piece of parchment paper or on a baking sheet. Get used to the way the salt falls from your hands; experience the illicit thrill of using so much of something we’ve all been taught to fear.

First, dry your hands so the salt won’t stick to your skin. Grab a palmful of salt and relax. Jerky or robotic hand motions make for uneven salting. See how the salt lands. If it lands unevenly, then it means you’re seasoning your food unevenly. Pour the salt back into the bowl, and try again. The more your wrist flows, the more evenly the salt will land.

This isn’t to say that you never want to use a pinch of salt, which can be used like a nail-polish-size bottle of touch-up car paint to fix a scratch on a fender. It might not have much potential to repair major damage, but applied precisely and judiciously, it will yield flawless results. Use a pinch when you want to make sure each bite is salted just so: slices of avocado atop a piece of grilled bread, halved hard-boiled eggs, or tiny, perfect caramels. But try to attack a chicken or a tray of butternut squash slices with the pinch, and your wrist will give out long before you’re done.

Salt and Pepper

While it’s true that where there’s pepper there should almost always be salt, the inverse isn’t necessarily so. Remember, salt is a mineral and an essential nutrient. When salted, food undergoes a number of chemical reactions that change the texture and flavour of meat from within.

Pepper, on the other hand, is a spice, and proper spice usage is primarily guided by geography and tradition. Consider whether pepper belongs in a dish before you add it. Though French and Italian cooks make abundant use of black pepper, not everyone does. In Morocco, shakers of cumin are commonly set on the table along with salt. In Turkey, it’s usually some form of ground chilli powder. In many Middle Eastern countries, including Lebanon and Syria, it’s the blend of dried thyme, oregano, and sesame seeds known as za’atar. In Thailand, sugar can be found alongside chilli paste, while in Laos, guests are often brought fresh chillies and limes. It doesn’t make any more sense to automatically season everything with pepper than it would to add cumin or za’atar to every dish you cook. (To learn more about spices used around the world, refer to The World of Flavour here.)

When you do use black pepper, look for Tellicherry peppercorns, which ripen on the vine longer than other varieties, and therefore develop more flavour. Grind them at the last moment onto a salad, a toast smeared with creamy burrata and drizzled with oil, sliced ripe tomatoes, Pasta Cacio e Pepe, or slices of perfectly cooked steak. Add a few whole peppercorns to a brine, braise, sauce, soup, stock, or pot of beans as you set it on the stove or slip it into the oven. In liquid, an early addition of whole spices initiates a flavour exchange: as the spices absorb liquid, they relinquish some of their volatile aromatic compounds, gently flavouring the liquid in a way that a little sprinkle at the end of cooking could never achieve.

Spices, like coffee, always taste better when ground just before use. Flavour is locked within them in the form of aromatic oils, which are released upon grinding, and again upon heating. The slow leak of time causes preground spices to relinquish flavour. Purchase whole spices whenever you can, and grind them with a mortar and pestle or spice grinder as you use them, to experience the powerful release of aromatic oils. You’ll be astonished by what a huge difference it makes in your cooking.

Salt and Sugar

Don’t abandon everything you know about salt when you turn to making dessert. We’re taught to think of salt and sugar existing in contrast to, rather than in concert with, one another: food is either sweet or savoury. But remember that the primary effect salt has on food is to enhance flavour, and even sweets benefit from this boost. Just as a little sweetness can amplify flavours in a savoury dish—whether in the form of caramelised onions, balsamic vinaigrette, or a spoonful of applesauce served with pork chops—salt will also improve a sweet dessert. To experience what salt does for sweets, divide your next batch of cookie dough and omit salt from half. Taste cookies from both batches side by side. Because salt will have done its aroma- and taste-enhancing work, you’ll be astounded by the notes of nuttiness, caramel, and butter you detect in the salted cookies.

The foundational ingredients of sweets are some of the blandest in the kitchen. Just as you’d never leave flour, butter, eggs, or cream unseasoned in a savoury dish, so should you never leave them unseasoned in a dessert. Usually just a pinch or two of salt whisked into a dough, batter, or base is enough to elevate flavours in pie and cookie doughs, cake batters, tart fillings, and custards alike.

Considering how you plan to eat a dessert can help you decide which type, or types, of salt to use. For example, use fine salt that will dissolve evenly in chocolate cookie dough, and then top it with a flakier one such as Maldon for a pleasant crunch.

Layering Salt

From capers to bacon to miso paste to cheese, there are many sources of salt beyond the crystals we add directly into our food. Working more than one form of salt into a dish is what I call layering salt, and it’s a terrific way to build flavour.

When layering salt, think about the dish as a whole and consider all of the various forms of salt you hope to add before you begin. Neglecting to account for the later addition of a crucial salty ingredient could result in oversalting. Think of layering salt the next time you make Caesar Dressing, which has several salty ingredients—anchovies, Parmesan, Worcestershire sauce, and salt. Garlic, which I like to pound with a pinch of salt in a mortar and pestle into a smooth paste, is a fifth source of salt. Since making a delicious, balanced dressing depends on working in the right amounts of each of those—and other, unsalted—ingredients, refrain from adding salt crystals until you’re sure that you’ve added the right amount of everything else.

First, make a stiff, unsalted mayonnaise by whisking oil into egg yolks, drop by drop (find more specific instructions for making mayonnaise by hand here–here). Next, work in initial amounts of pounded anchovies, garlic, grated cheese, and Worcestershire. Then, add vinegar and lemon. Taste. It will need salt. But does it also need more anchovy, cheese, garlic, or Worcestershire? If so, add salt in the form of any of those ingredients. But do it gradually, stopping to taste and adjust with acid as needed. It may take several rounds of tasting and adjusting to get it right. As with any dish with multiple forms of salt, add crystals only after you’re satisfied with the balance of all other flavours. And to be sure you’ve got it right, dip a lettuce leaf or two into the finished dressing to taste, to ensure that the combination delivers the zing! you’re after.

Even when following a recipe, if you realise that a dish needs more salt, take a moment to think about where that salt should come from.

Balancing Salt

No matter how attentive you are while cooking, there will be times you sit down to eat only to discover that you’ve underseasoned your dinner. Some foods forgive undersalting more readily than others. You can easily adjust a salad at the table with a pinch of salt. Stir a shaving of salty Parmesan into a cup of soup to bump up its seasoning. Other foods don’t respond as well: no amount of salty sauce or cheese or meat could ever make up for bland pasta—the tongue will always know the water was nowhere nearly as salty as the sea. Roasted and braised meats cannot pardon the transgression of underseasoning, either.

Ever since witnessing a series of underseasoning disasters at Chez Panisse, I’ve been obsessed with preventing it. There was the day a cook forgot to add salt to the pizza dough altogether, an accident we didn’t notice until the taster, when nothing could be done but remove pizza from the menu. There was the time I braised chicken legs that had been marked “salted” but clearly were not, a mistake that went undiscovered until I pulled the chicken from the oven and tasted it. Since sprinkling the surface of cooked meat will do little to make up for the lack of seasoning within, the only thing we could do was shred the meat, season it, and turn it into a ragù to be served with pasta. The instance of underseasoning that made the biggest impression on me, though, was the time a very senior cook undersalted his lasagna, which he had already cut into one hundred pieces for that night’s service. Since salting the top would do little to correct a mistake that had been made from within, as the intern I was given the task of gingerly lifting each of the twelve layers on each of the one hundred pieces of lasagna to sneak a few grains of salt into each one. After that, I’ve never underseasoned a lasagna.

You will also inevitably oversalt. We all do. It might happen soon after you become a member of the newly converted, now awakened to the power of salt. You might grow cavalier, like I did as a young cook with those pork roasts, and start to use so much salt, you render everything inedible for a while. It could happen when you’re simply not paying attention. It’s not that big a deal. We all make mistakes from time to time. I certainly still do.

There are a handful of fixes for oversalting. But none involves serving something terribly salty alongside something terribly bland. Intentional blandness won’t ever cancel out oversalting.

Dilute

Add more unseasoned ingredients to increase the total volume of the dish. More of anything that’s unsalted will work to balance out what’s salted, but bland, starchy, and rich things are particularly helpful in these circumstances, because just a small amount of them can help balance out a relatively large amount of food. Add bland rice or potatoes to an overseasoned soup, or olive oil to an oversalted mayonnaise. While water evaporates from a boiling soup, stock, or sauce, salt won’t, and what’s left behind will be overly salty. The solution here is simple: add more water or stock. If you overseason a dish made with many ingredients mixed together, add more of the main ingredient and adjust everything else until it’s all balanced again.

Halve

If you’ve already put the dish together and diluting will yield more food than you’ll be able to use, then divide the oversalted amount and correct only half of it. Depending on what it is, you may be able to refrigerate or freeze the rest until you can get around to adjusting and using it. Or, you might have to face the sad reality of throwing it out. But that’s better than using thirty dollars’ worth of olive oil to correct a batch of mayonnaise, and then only using a quarter of it.

Balance

Sometimes, food that seems salty isn’t actually oversalted; it just needs to be balanced with some acid or fat. Doctor up a spoonful of the dish with a few drops of lemon juice or vinegar, a little olive oil, or some of each. If it tastes better, then apply the changes to the whole batch.

Select

Foods cooked in liquid, such as beans or braises, can often be salvaged if the salty cooking liquid is discarded. If beans are too salty, change out the water. Make refried beans or turn the beans, but not their liquid, into soup, adding unseasoned broth and vegetables. If braised meat is just a little too salty, serve it without the liquid and try to balance it with a rich, acidic condiment such as crème fraîche. Serve a lightly seasoned starch or starchy vegetable alongside it to act as a foil.

Transform

Shred an oversalted piece of meat to turn it into a new dish where it’s just one ingredient of many—a stew, chilli, a soup, hash, ravioli filling. Add more salt to oversalted raw, flaky, white fish and turn it into baccalà, or salt cod.

Admit Defeat

Sometimes the best thing you can do is call it a loss and start over. Or order some pizza. It’s okay. It’s just dinner—you’ll get another chance tomorrow.

Never despair. View mistakes of under- or overseasoning as opportunities for learning. Not long after my salt epiphany over polenta with Cal, I was tasked with making some corn custards for the vegetarian guests in the restaurant. It was the first time I was trusted with cooking an entire dish from start to finish. I could hardly believe that paying guests would be eating something I cooked! It was thrilling and terrifying, all at once. I made the custard just as I’d been taught: cooking onions until soft, adding corn I’d stripped from the ears, steeping the cobs in cream to infuse it with sweet corn flavour, making a simple custard base with that cream and eggs, and then combining everything and gently baking it in a water bath until barely set. I was thrilled with how silky the custards had turned out, and towards the end of the night the chef came by and tasted a spoonful. Seeing the hope in my eyes, he graciously told me I’d done a good job, and then gingerly added that next time, I should increase the seasoning. Even though he’d delivered the criticism just about as gently as any chef ever could, I was floored, and completely embarrassed. I’d been following all of the instructions for making the custards so intently that I’d completely forgotten the most important rule in our kitchen—one that I had thought I’d already internalised, but clearly hadn’t: taste everything, every step of the way. I’d never tasted the onions, the corn, or the custard mixture. Not once.

After that experience, tasting became reflexive in a whole new way. Within a few months, I was consistently cooking the most delicious food I’d ever made, and it was all because of a single tweak in my approach. I’d learned how to salt.

Develop a sense for salt by tasting everything as you cook, early and often. Adopt the mantra Stir, taste, adjust. Make salt the first thing you notice as you taste and the last thing you adjust before serving a dish. When constant tasting becomes instinctive, you can begin to improvise.

Improvising with Salt

Cooking isn’t so different from jazz. The best jazz musicians seem to improvise effortlessly, whether by embellishing standards or by stripping them down. Louis Armstrong could take an elaborate melody and distil it down to a single note on his horn, while Ella Fitzgerald could take an utterly simple tune and endlessly elaborate upon it with her extraordinary voice. But in order to be able to improvise flawlessly, they had to learn the basic language of music—the notes—and develop an intimate relationship with the standards. The same is true for cooking; while a great chef can make improvisation look easy, the ability to do so depends on a strong foundation of the basics.

Salt, Fat, Acid, and Heat are the building blocks of that foundation. Use them to develop a repertoire of basic dishes that you can cook any time, anywhere. Eventually, like Louis or Ella, you’ll be able to simplify or embellish your cooking at the drop of a porkpie hat. Begin by incorporating everything you’ve learned about salt into all of your cooking, from the casual frittata to the holiday roast.

The three basic decisions involving salt are: When? How much? In what form? Ask yourself these three questions every time you set out to cook. Their answers will begin to form a road map for improvisation. One day soon, you’ll surprise yourself. It might be when, shortly after standing before a near-empty fridge, convinced you don’t have the makings for anything worth eating, you discover a wedge of Parmesan. Twenty minutes later, you could be tucking into the most perfectly seasoned bowl of Pasta Cacio e Pepe you’ve ever tasted. Or, it might be after an unplanned shopping spree at the farmers’ market with friends. Returning home with an abundance of produce, you’ll lay it all out on the worktop, pull the chicken you seasoned the night before out from the fridge, and preheat the oven without skipping a beat. Pouring your friends a glass of wine, you’ll offer them a snack of a few sliced cucumbers and radishes sprinkled with flaky salt. Without a second thought, you’ll add a palmful of salt to the boiling pot of water on the stove, then taste and adjust it before blanching the turnips and their greens. As your friends take their first bites, they’ll ask you to share your culinary secrets. Tell them the truth: you’ve mastered using the most important element of good cooking—salt.