Читать книгу Salt, Fat, Acid, Heat - Samin Nosrat - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

Anyone can cook anything and make it delicious.

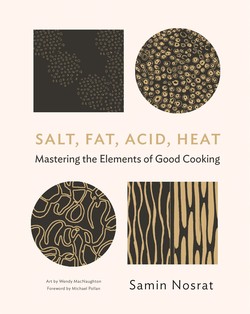

Whether you’ve never picked up a knife or you’re an accomplished chef, there are only four basic factors that determine how good your food will taste: salt, which enhances flavour; fat, which amplifies flavour and makes appealing textures possible; acid, which brightens and balances; and heat, which ultimately determines the texture of food. Salt, Fat, Acid, and Heat are the four cardinal directions of cooking, and this book shows how to use them to find your way in any kitchen.

Have you ever felt lost without a recipe, or envious that some cooks can conjure a meal out of thin air (or an empty refrigerator)? Salt, Fat, Acid, and Heat will guide you as you choose which ingredients to use, how to cook them, and why last-minute adjustments will ensure that food tastes exactly as it should. These four elements are what allow all great cooks—whether award-winning chefs or Moroccan grandmothers or masters of molecular gastronomy—to cook consistently delicious food. Commit to mastering them and you will too.

As you discover the secrets of Salt, Fat, Acid, and Heat, you’ll find yourself improvising more and more in the kitchen. Liberated from recipes and precise shopping lists, you’ll feel comfortable buying what looks best at the farmer’s market or butcher’s counter, confident in your ability to transform it into a balanced meal. You’ll be better equipped to trust your own palate, to make substitutions in recipes, and cook with what’s on hand. This book will change the way you think about cooking and eating, and help you find your bearings in any kitchen, with any ingredients, while cooking any meal. You’ll start using recipes, including the ones in this book, like professional cooks do—for the inspiration, context, and general guidance they offer, rather than by following them to the letter.

I promise this can happen. You can become not only a good cook, but a great one. I know, because it happened to me.

I have spent my entire life in pursuit of flavour.

As a child, I found myself in the kitchen only when Maman enlisted me and my brothers to peel raw broad beans or pick fresh herbs for the traditional Persian meals she served us every night. My parents left Tehran for San Diego on the eve of the Iranian Revolution, shortly before I was born in 1979. I grew up speaking Farsi, celebrating No-Ruz, the Iranian New Year, and attending Persian school to learn how to read and write, but the most delightful aspect of our culture was the food—it brought us together. Rare were the nights when our aunts, uncles, or grandparents didn’t join us at the dinner table, which was always filled with plates mounded high with herbs, platters of saffron rice, and fragrant pots of stew. Invariably, I was the one who snagged the darkest, crunchiest pieces of tahdig, the golden crust that formed at the bottom of every pot of Persian rice Maman made.

Though I certainly loved to eat, I never imagined I’d become a chef. I graduated from high school with literary ambitions, and moved north to study English literature at UC Berkeley. I remember someone mentioning a famous restaurant in town during my freshman orientation, but the idea of dining there never occurred to me. The only restaurants I’d ever eaten at were the Persian kebab places in Orange County my family trekked to each weekend, the local pizza joint, and fish taco stands at the beach. There were no famous restaurants in San Diego.

Then I fell in love with Johnny, a rosy-cheeked, sparkly-eyed poet who introduced me to the culinary delights of his native San Francisco. He took me to his favourite taqueria, where he taught me how to construct an order for the perfect Mission burrito. Together, we tasted baby coconut and mango ice creams at Mitchell’s. We’d sneak up the stairs of Coit Tower late at night to eat our slices of Golden Boy Pizza, watching the city twinkle below. Johnny had always wanted to dine at Chez Panisse but had never had the chance. It turned out that the famous restaurant I’d once heard about was an American institution. We saved up for seven months and navigated a labyrinthine reservation system to secure a table.

When the day finally arrived, we went to the bank and exchanged the shoe box of quarters and dollar bills for two crisp hundred-dollar bills and two twenties, dressed up in our nicest outfits, and zoomed over in his classic convertible VW Beetle, ready to eat.

The meal, of course, was spectacular. We ate frisée aux lardons, halibut in broth, and guinea hen with tiny chanterelle mushrooms. I’d never eaten any of those things before.

Dessert was chocolate soufflé. When the server brought it to us, she showed me how to poke a hole in the top with my dessert spoon and then pour in the accompanying raspberry sauce. She watched me take my first bite, and I ecstatically told her it tasted like a warm chocolate cloud. The only thing, in fact, that I could imagine might improve the experience was a glass of cold milk.

What I didn’t know, because I was inexperienced in the ways of fancy food, was that for many gourmands the thought of consuming milk after breakfast is childish at best, revolting at worst.

But I was naïve—though I still contend that there’s nothing like a glass of cold milk with a warm brownie, at any time of day or night—and in that naïveté, she saw sweetness. The server returned a few minutes later with a glass of cold milk and two glasses of dessert wine, the refined accompaniment to our soufflé.

And so began my professional culinary education.

Shortly afterwards, I wrote a letter to Alice Waters, Chez Panisse’s legendary owner and chef, detailing our dreamy dinner. Inspired, I asked for a job waiting tables. I’d never considered restaurant work before, but I wanted to be a part of the magic I’d experienced at Chez Panisse that night, even in the smallest way.

When I took the letter to the restaurant along with my résumé, I was led into the office and introduced to the floor manager. We instantly recognised each other: she was the woman who’d brought us the milk and dessert wine. After reading my letter, she hired me on the spot. She asked if I could return the next day for a training shift.

During that shift, I was led through the kitchen into the downstairs dining room, where my first task was to vacuum the floors. The sheer beauty of the kitchen, filled with baskets of ripe figs and lined with gleaming copper walls, mesmerised me. Immediately I fell under the spell of the cooks in spotless white chef’s coats, moving with grace and efficiency as they worked.

A few weeks later I was begging the chefs to let me volunteer in the kitchen.

Once I convinced the chefs that my interest in cooking was more than just a dalliance, I was given a kitchen internship and gave up my job as a waitress. I cooked all day and at night I fell asleep reading cookbooks, dreaming of Marcella Hazan’s Bolognese sauce and Paula Wolfert’s hand-rolled couscous.

Since the menu at Chez Panisse changes daily, each kitchen shift begins with a menu meeting. The cooks sit down with the chef, who details his or her vision for each dish while everyone shells peas or peels garlic. He might talk about his inspiration for the meal—a trip to the coast of Spain, or a story he’d read in the New Yorker years ago. She might even detail a few specifics—a particular herb to use, a precise way to slice the carrots, a sketch of the final plate on the back of a scrap of paper—before assigning a dish to each cook.

As an intern, sitting in on menu meetings was inspiring and terror-inducing in equal measure. Gourmet magazine had just named Chez Panisse the best restaurant in the country, and I was surrounded by some of the best cooks in the world. Just hearing them talk about food was enormously educational. Daube provençal, Moroccan tagine, calçots con romesco, cassoulet toulousain, abbacchio alla romana, maiale al latte: these were the words of a foreign language. The names of the dishes were enough to send my mind reeling, but the cooks rarely consulted cookbooks. How did they all seem to know how to cook anything the chef could imagine?

I felt like I’d never catch up. I could hardly imagine the day would come when I’d be able to recognise all of the spices in the kitchen’s unlabelled jars. I could barely tell cumin and fennel seeds apart, so the thought of getting to a point where I could ever appreciate the nuanced differences between Provençal bouillabaisse and Tuscan cacciucco (two Mediterranean seafood stews that appeared to be identical) seemed downright impossible.

I asked questions of everyone, every day. I read, cooked, tasted, and also wrote about food, all in an effort to deepen my understanding. I visited farms and farmers’ markets and learned my way around their wares. Gradually the chefs gave me more responsibility, from frying tiny, gleaming anchovies for the first course to folding perfect little ravioli for the second to butchering beef for the third. These thrills sustained me as I made innumerable mistakes—some small, such as being sent to retrieve coriander and returning with parsley because I couldn’t tell the difference, and some large, like the time I burned the rich beef sauce for a dinner we hosted for the First Lady.

As I improved, I began to detect the nuances that distinguish good food from great. I started to discern individual components in a dish, understanding when the pasta water and not the sauce needed more salt, or when an herb salsa needed more vinegar to balance a rich, sweet lamb stew. I started to see some basic patterns in the seemingly impenetrable maze of daily-changing, seasonal menus. Tough cuts of meat were salted the night before, while delicate fish fillets were seasoned at the time of cooking. Oil for frying had to be hot—otherwise the food would end up soggy—while butter for tart dough had to remain cold, so that the crust would crisp up and become flaky. A squeeze of lemon or splash of vinegar could improve almost every salad, soup, and braise. Certain cuts of meat were always grilled, while others were always braised.

Salt, Fat, Acid, and Heat were the four elements that guided basic decision making in every single dish, no matter what. The rest was just a combination of cultural, seasonal, or technical details, for which we could consult cookbooks and experts, histories, and maps. It was a revelation.

The idea of making consistently great food had seemed like some inscrutable mystery, but now I had a little mental checklist to think about every time I set foot in a kitchen: Salt, Fat, Acid, Heat. I mentioned the theory to one of the chefs. He smiled at me, as if to say, “Duh. Everyone knows that.”

But everyone didn’t know that. I’d never heard or read it anywhere, and certainly no one had ever explicitly related the idea to me. Once I understood it, and once it had been confirmed by a professional chef, it seemed inconceivable that no one had ever framed things in this way for people interested in learning how to cook. I decided then I’d write a book elucidating the revelation for other amateur cooks.

I picked up a legal pad and started writing. That was seventeen years ago. At twenty years old, I’d been cooking for only a year. I quickly realised I still had a lot to learn about both food and writing before I could begin to instruct anyone else. I set the book aside. As I kept reading, writing, and cooking, I filtered everything I learned through my newfound understanding of Salt, Fat, Acid, and Heat into a tidy system of culinary thinking.

Like a scholar in search of primary sources, a desire to experience authentic versions of the dishes I loved so much at Chez Panisse took me to Italy. In Florence, I apprenticed myself to the groundbreaking Tuscan chef Benedetta Vitali at her restaurant, Zibibbo. At first it was a constant challenge to work in an unfamiliar kitchen where I barely spoke the language, where temperatures were measured in Celsius, and where measurements were metric. But my understanding of Salt, Fat, Acid, and Heat quickly gave me my bearings. I might not have known all of the specifics, but the way Benedetta taught me to brown meat for ragù, heat olive oil for sautéing, season the pasta water, and use lemon juice as a foil for rich flavours echoed what I had learned back in California.

I spent my days off in the hills of Chianti with Dario Cecchini, an eighth-generation butcher with a huge personality and an even bigger heart. Dario took me under his wing, teaching me about whole-animal butchery and Tuscan food heritage with equal vigour. He took me all over the region to meet farmers, vintners, bakers, and cheese makers. From them, I learned how geography, the seasons, and history have shaped Tuscan cooking philosophy over the course of centuries: fresh, if modest, ingredients, when treated with care, can deliver the deepest flavours.

My pursuit of flavour has continued to lead me around the world. Fuelled by curiosity, I’ve sampled my way through the oldest pickle shop in China, observed the nuanced regional differences of lentil dishes in Pakistan, experienced the way a complicated political history has diluted flavours in Cuban kitchens by restricting access to ingredients, and compared varieties of heirloom corn in Mexican tortillas. When unable to travel, I have read extensively, interviewed immigrant grandmothers, and tasted their traditional cooking. No matter my circumstances or whereabouts, as reliably as the points on a compass, Salt, Fat, Acid, and Heat have set me on the path to good food every time I cook.

I returned to Berkeley and went to work for Christopher Lee, my mentor at Chez Panisse, who’d recently opened his own Italian restaurant, Eccolo. I quickly took the role of chef de cuisine. I made it my job to develop exquisite familiarity with the way an ingredient or a food behaved and then follow the crumb trail of kitchen science to understand why. Instead of simply telling the cooks under my watch to “taste everything,” I could really teach them how to make better decisions. A decade after I first discovered my theory of Salt, Fat, Acid, and Heat, I’d gathered enough information to begin teaching the system to my own young cooks.

Seeing how useful the lessons of Salt, Fat, Acid, and Heat had been for professional cooks, I used them as a rubric when my journalism teacher, Michael Pollan, hired me to teach him how to cook while writing Cooked, his book about the natural history of cooking. Michael quickly noticed my obsession with the four elements of good cooking and encouraged me to formalise the curriculum and begin teaching it to others. So I did. I’ve taught the system in cooking schools, senior centres, middle schools, and community centres. Whether the foods we cooked together were inspired by Mexican, Italian, French, Persian, Indian, or Japanese traditions, without exception, I’ve seen my students gain confidence, prioritise flavour, and learn to make better decisions in the kitchen, improving the quality of everything they cook.

Fifteen years after arriving at the idea for this book, I began to write in earnest. After first immersing myself in the lessons of Salt, Fat, Acid, and Heat, and then spending years teaching them to others, I’ve distilled the elements of good cooking into its essence. Learn to navigate Salt, Fat, Acid, and Heat, and you can make anything taste good. Keep reading, and I’ll teach you how.