Читать книгу One Man's Wilderness, 50th Anniversary Edition - Sam Keith - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER TWO

The Birth of a Cabin

May 22nd. Up with the sun at four to watch the sunrise and the sight of the awakening land. It seems a shame for eyes to be shut when such things are going on, especially in this big country. I don’t want to miss anything. A heavy white frost twinkled almost as if many of its crystals were suspended in the air. New ice, like a thin pane of glass, sealed the previously open water along the edge of the lake. The peaks, awash in the warm yellow light, contrasted sharply with their slopes still in shadow.

Soon I had a fire snapping in the stove, and shortly afterward could no longer see my breath inside the cabin. A pan of water was heating alongside the kettle. That business of breaking a hole in the ice and washing up out there sounds better than it feels. I prefer warm water and soap. Does a better job, too.

Thick bacon sliced from the slab sizzled in the black skillet. I poured off some of the fat and put it aside to cool. Time now to put the finishing touches to the sourdough batter. As I uncovered it I could smell the fermentation. I gave it a good stirring, then sprinkled half a teaspoonful of baking soda on top, scattered a pinch of salt, and dripped in a tablespoon of bacon fat. When these additions were gently folded into the batter, it seemed to come alive. I let it stand for a few minutes while bacon strips were laid on a piece of paper towel and excess fat was drained from the pan. Then I dropped one wooden spoonful of batter, hissing onto the skillet. When bubbles appear all over, it’s time to flip.

Brown, thin, and light—nothing quite like a stack of sourdough hotcakes cooked over a wood fire in the early morning. I smeared each layer with butter and honey and topped the heap with lean bacon slices. While I ate I peered out the window at a good-looking caribou bedded down on the upper benches. Now that’s a breakfast with atmosphere!

Before doing the dishes, I readied the makings of the sourdough biscuits. These would be a must for each day’s supper. The recipe is much the same as for hotcakes, but thicker, a dough that is baked.

It was a good morning to pack in the rest of the gear. I put some red beans in a pot to soak and took off. Last night’s freeze had crusted the snow, and it made the traveling easier. About a mile down the lakeshore a cock ptarmigan clattered out of the willow brush, his neck and head shining a copper color in the sun, his white wings vibrating, then curving into a set as he sailed. His summer plumage was beginning to erase the white of winter. Crrr … uck … a … ruck … urrrrrrrrr. His ratcheting call must have brought everything on the mountain slopes to attention.

A stack of sourdough pancakes drizzled with syrup and topped with bacon.

The last load was the heaviest. It was almost noon before I got back to the cabin, and none too soon because rain clouds were gathering over the mountains to the south.

The rain came slanting down, hard-driven by the wind. I busied myself getting gear and groceries organized. Anyone living alone has to get things down to a system—know where things are and what the next move is going to be. Chores are easier if forethought is given to them and they are looked upon as little pleasures to perform instead of inconveniences that steal time and try the patience.

When the rain stopped its heavy pelting, I went prospecting for a garden site. A small clearing on the south side of the cabin and away from the big trees was the best place I could find. Here it would get as much sun as possible.

Frost was only inches down, so there would be no planting until June. Spike’s grub hoe could scuff off the ground cover later on and stir up the top soil as deep as the frost would permit. I had no fertilizer. I suppose I might experiment with the manure of moose and caribou, but it would be interesting to see what progress foreign seeds would make in soil that had nourished only native plants.

By suppertime the biscuits were nicely puffed and ready to bake. There was no oven in the stove, but with tinsnips I cut down a coffee can so it stood about two inches high, and placed it bottomside up atop the stove. On this platform I set the pan of three swollen biscuits and covered it with a gas can tin about six inches deep.

In about fifteen minutes the smell of the biscuits drifted out to the woodpile. I parked the axe in the chopping block. Inside, I dampened a towel and spread it over the biscuits for about two minutes to tenderize the crust. The last biscuit mopped up what was left of the onion gravy. Mmmm.

When will I ever tire of just looking? I set up the spotting scope on the tripod. Three different eyepieces fit into it: a 25-power, a 40-power, and a 60-power. That last one hauls distant objects right up to you, but it takes a while to get the knack of using it because the magnification field covers a relatively small area.

This evening’s main attraction was a big lynx moving across a snow patch. I had seen a sudden flurrying of ptarmigan just moments before, and when I trained the scope on the action, there was the cat taking his time, stopping now and then as if watching for a movement in the timber just ahead of him.

I switched to a more powerful eyepiece and there he was again, bigger and better, strolling along, his hips seeming to be higher than his shoulders, his body the color of dark gray smoke, his eyes like yellow lanterns beneath his tufted ears. Even from the distance I could sense his big-footed silence.

I went to sleep wondering if the lynx had ptarmigan for supper.

May 23rd. Dense fog this morning. A ghostly scene. Strange how much bigger things appear in the fog. A pair of goldeneye ducks whistled past low and looked as big as honkers to me.

After breakfast I inspected the red beans for stones, dumped them into a fresh pot of water from the lake, and let them bubble for a spell on the stove. I sliced some onions. What in the world would I do without onions? I read one time that they prevent blood clots. Can’t afford a blood clot out here. I threw the slices into the beans by the handful, showered in some chili powder and salt, and stirred in a thick stream of honey. I left the pot to simmer over a slow fire. Come suppertime they should be full of flavor.

I took a tour back through the spruce timber. It didn’t take much detective work to see how hard the wind had blown during the winter, both up and down the lake. Trees were down in both directions. That was something else to think about. Did the wind blow that much harder in the winter?

Hope Creek has cut a big opening into the lake ice. That could be where the ducks were headed this morning. Was it too early to catch a fish? I took the casting rod along to find out. The creek mouth looked promising enough with its ruffled water swirling into eddies that spun beneath the ice barrier. I worked a metal spoon deep in the current, jerked it toward me and let it drift back. Not a strike after several casts. If the fish were out there, they were not interested. No sign of the ducks either.

When the fog finally cleared the face of the mountain across the ice, I sighted a bunch of eleven Dall ewes and lambs. Five lambs in all, a good sign. A mountain has got to be lonely without sheep on it.

The rest of the day I devoted to my tools. I carved a mallet head out of a spruce chunk, augered a hole in it, and fitted a handle to it. This would be a useful pounding tool, and I hadn’t had to pack it in either. The same with the handles I made for the wood augers, the wide-bladed chisel, and the files—much easier to pack without the handles already fitted to them.

I sharpened the axe, adze, saws, chisels, wood augers, drawknife, pocket knife, and bacon slicer. The whispering an oil stone makes against steel is a satisfying sound. You can almost tell when the blade is ready by the crispness of the sound. A keen edge not only does a better job, it teaches a man to have respect for the tool. There is no leeway for a “small” slip.

While I pampered my assault kit for the building of the cabin, the sky turned loose a heavy shower and thundered Midwestern style. The echoes rumbled and tumbled down the slopes and faded away into mutterings. The shrill cries of the terns proclaimed their confusion.

The ice attempted to move today. Fog and thunder have taken their toll. I can see the rough slab edges pushed atop each other along the cracks. The winter freight will be moving down the lake soon, through the connecting stream and down the lower lake to the funnel of the Chilikadrotna River.

After supper I made log-notch markers out of my spruce stock. They are nothing more than a pair of dividers with a pencil on one leg, but with them I can make logs fit snugly. This is not going to be a butchering job. I can afford the time for pride to stay in charge.

These simple hand tools would challenge anyone’s self-reliance.

I sampled the red beans again before turning in for the night. The longer they stay in the pot the more flavor they have.

The woodpile needs attention. I must drop a few spruce snags and buck them up into sections. Dry standing timber makes the best firewood.

Ho, hum. I’m anxious to get started on that cabin, but first things first. Tomorrow will have to be a woodcutting day.

May 25th. The mountains are wearing new hats this morning. The rain during the night was snow at the higher levels.

I built up the wood supply yesterday and this morning. There is a rhythm to the saw as its teeth eat back and forth in the deepening cut, but I must admit I enjoy the splitting more. To hit the chunk exactly where you want to and cleave it apart cleanly—there’s a good sound to it and satisfaction in an efficient motion. Another reward comes from seeing those triangular stove lengths pile up. Then the grand finale! Drive the ax into the block, look around, and contemplate the measure of what you have done.

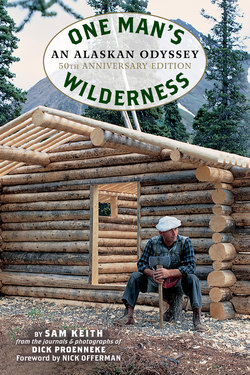

Bedding the side foundation logs in the beach gravel cabin site. Soon the cabin will be born.

Breakup was not the spectacular sight it was last year. A big wind would have cleared the thin ice out yesterday. As I loaded tools on the packboard this afternoon, the rotted ice began to flow past in quiet exit.

At the construction site several hundred yards down the lakeshore, I found my logs were not as badly checked as I had first thought. The checking was only evident on the weathered sides. The logs were well seasoned and light in weight for their length.

When you have miles and miles of lakefront and picture views to consider, it is difficult to select a building site. The more a man looks, the fussier he gets. I had given much thought to mine. It sat atop a knoll about seventy-five feet back from a bight in the shoreline. There was a good beach for landing a canoe, and a floatplane also could be brought in there easily.

The wind generally blew up or down the lake. From either direction the cabin would be screened by spruce trees and willow brush. The knoll was elevated well above any visible high-water marks. Just over 100 yards away was Hope Creek, and even though the water from the lake was sweet and pure, Hope Creek carried the best ever from the high places. At its mouth could usually be found fish, too.

There were two things that bothered me just a little, and I gave them serious consideration before making the final decision. It was possible that after a continuous heavy rain and the resulting runoff from the mountains, Hope Creek could overflow and come churning through the timber behind me. If that happened, I felt I was still high enough to handle the situation. Perhaps some engineering would be necessary to divert the flow until the creek tamed down and returned to its channel.

It was also a possibility, though quite remote, that a slide or a quake might choke the Chilikadrotna River, which was the drainpipe of the Twins. Anytime the volume of water coming into the country was greater than what was going out, the lake level was going to rise. If the Chilikadrotna were to plug seriously, the country would fill up like a giant bathtub. I didn’t like to think about that. Finally I decided such a catastrophe would rule out any site, and if a man had to consider all of nature’s knockout punches, he would hesitate to build anywhere.

So I had taken the plunge and cleared the brush. I had grubbed out a shallow foundation, had hauled up beach gravel and had spread it to a depth of several inches over an area roughly twenty feet by twenty feet. I felt I had made the best possible choice.

I stood with hands on hips looking at the plot of gravel and the pile of logs beside it. The logs were decked, one layer one way and the next at right angles to it so air could circulate through the pile. On that floor of gravel, from those logs, the house would grow. I could see it before me because I had sketched it so many times. It would be eleven feet by fifteen feet on the inside. Its front door would face northwest, and the big window would look down the lake to the south and west. It would nestle there as if it belonged.

A pile of logs. Which ones to start with. Why not the largest and most crooked for the two side foundation logs? They would be partly buried in the gravel anyway. Save the best ones to show off to the best possible advantage. I rolled the logs around until I was satisfied I had found what I was looking for.

One log in particular required considerable hewing to straighten it. I must say white spruce works up nicely with axe and drawknife, much like white pine. If I keep the edges of my tools honed, it will be a pleasure to pile up chips and shavings.

I bedded the two side logs into the gravel, then selected two end logs, which I laid across them to form the eleven-by-fifteen-foot interior. Next I scribed the notches on the underside of the end logs, on each side so the entire pattern of the notch was joined and penciled. Everything inside the pencil patterns would have to be removed. Four notches to cut out.

To make a notch fit properly, you can’t rush it. Make several saw cuts an inch or two apart almost down to the pencil line and whack out the chunks with the axe until the notch is roughly formed. Then comes the finish work, the careful custom fit. I have just the tool for the job. At first I thought the character in the hardware store gouged me a little when he charged more than seven dollars for a gouge chisel (half round), but next to my axe I consider it my most valuable tool. Just tap the end of its handle with the spruce mallet and the sharp edge moves a curl of wood before it, right to the line. It smooths the notch to perfection.

Notice how the notches fit snugly over the tops of the logs below them, as if fused.

The four notches rolled snugly into position over the curve of the side foundation logs beneath them.

Well, there’s the first course, the first four logs, and those notches couldn’t fit better. That’s the way they’re all going to fit.

Enough for this evening. The job has begun. It should be good going from here up to the eave logs and the start of the gable ends. Tomorrow should see more working and less figuring.

I wanted a salad for supper. Fireweed greens make the best, and fireweed is one of the most common plants in this country. Its spikes of reddish pink brighten the land. They start blooming from the bottom and travel up as the season progresses. When the blossoms reach the top, summer is almost gone.

I went down along the creek bed where a dwarf variety grows. None were in bloom yet. I squatted among the stems and slender leaves and picked the tender plant crowns into a bowl. Then I rinsed them in the creek.

Sprinkled with sugar and drizzled with vinegar, those wild greens gave the red beans just the tang needed.

May 26th. I should have a fish for this evening’s meal. It was a good morning to try for one down at the connecting stream.

There was still ice on the lower half of the lake. The way the ice was moving yesterday I thought the lake would be clear of it. Something is stalling the ice parade.

Traveling the lake shore, I nearly upended a time or two on the crusted snow. It was treacherous going. When I came to a good seat on the evergreens beneath a small spruce, I took advantage of it and proceeded to glass the slopes above the spruce timber.

First sighting was a cow moose with a yearling trailing her down country. While I watched them, I heard the bawling of caribou calves. It took me a few minutes to locate where all the noise was coming from. In a high basin I spotted seventy-five or more cows and calves. Across the lake ten Dall rams were in different positions of relaxation, and farther down I counted eleven lambs and nineteen ewes. Satisfied that there was plenty of game in the country, I trudged down to the stream and followed along its banks, through the hummocks of low brush, until I came to where it poured invitingly into the lower lake.

I waded out a few steps. My boots did not leak, but almost immediately the chill seeped through the woolens inside them. I cast a few times, letting the small metal lure ride out with the current, then retrieving it jerkily with twitches of the rod tip. Several more casts. Nothing.

Thumping a gouge chisel with a spruce chunk mallet to fashion a perfect notch.

Then it happened with the suddenness of a broken shoelace. As the lure came flashing toward me over the gravel, a pale shadow, almost invisible against the bottom, streaked in pursuit. Jaws gaped white, and the bright glint of the lure winked out as they closed over it. The line hissed, the rod tip hooped. The fish swerved out of the shallows, rolling a bulge of water before him as he bolted for the dropoff. He slashed the water white as I backed away with the rod held high, working him in to where he ran out of water and flopped his yellow spotted sides on the bank. A nineteen-inch lake trout. I thumped its head with a stone, and it shuddered out straight.

As I dressed it out, I examined its stomach. Not a thing in it. It is always interesting to see what a fish has been eating. Several times I have found mice in the stomachs of lake trout and arctic char. Now how does a mouse get himself into a jackpot like that? Does he fall in by accident, or does he venture for a swim? Tough to be a mouse in this country. From the air, the land, and the water his enemies wait to strike.

On the way back to the cabin, I repaired the log bridge over Hope Creek. All it needed was shoring up with a few boulders rolled against the log bracings on each end, which was easier to do now while the water was low.

I popped a batch of corn in bacon fat, salted and buttered it, and munched on it while I studied the sweep of the mountains. Before I left for the construction job, I shaped my biscuits, put them into a pan, and covered them to rise for supper. You always have to think ahead with biscuits and a lot of other things in the wilderness.

If I can fit eight logs a day, the cabin will go along at a good rate. That’s sixteen notches to cut out and tailor to fit. It is important to put the notch on the underside of a log and fit it down over the top of the one beneath. If you notch the topside, rain will run into it instead of dripping past in a shingle effect. Water settling into the notches can cause problems.

The sun shining on the green lake ice was so beautiful I had to stop work now and then just to look at it. That’s a luxury a man enjoys when he works for himself.

Browned trout filets, sourdough biscuits, and honey for the first fry of the spring.

For supper, I cut the trout into small chunks, dipped them into beaten egg, and rolled them in cornmeal. They browned nicely in the bacon fat, and my tender crusted sourdoughs did justice to the first fish fry of the season.

May 28th. Frost on the logs when I went to work at six a.m. I had to roll many of them around to get the ones I wanted. Sorting takes time, but matching ends is very important if the cabin is to look right.

The wind helped the ice along today. The upper lake is nearly two-thirds ice-free now.

Had my first building inspector at the job. A gray jay, affectionately known as camp robber, came in his drab uniform of gray and white and black to look things over from his perch on a branch end. The way he kept tilting his head and making those mewing sounds, I’d say he was being downright critical. I welcomed his company just the same.

May 29th. Only a few chunks of ice floating in the lake this morning. By noon there was no ice to be seen. It was good to see the lake in motion again. It was even better to slip the canoe into the water and paddle to work for a change, gliding silently along over a different pathway.

My logs are not as uniform as they could be. They have too much taper, which makes much more work. Just the same I like the accumulation of white chips and shavings all over the ground and the satisfaction that comes from making a log blend over the curve of the one beneath it as if it grew that way. You can’t rush it. I don’t want these logs looking as though a Boy Scout was turned loose on them with a dull hatchet.

This evening I hauled out Spike’s heavy trotline, tested it for strength, and baited its three hooks with some of the lake trout fins. I whirled it a few times, gave it a toss, and watched the stone sinker zip the slack line from the beach and land with a plop about fifty feet from the shore. Let’s see what is prowling the bottom these days.

It was raining slightly when I turned in. There’s no sleeping pill like a good day’s work.

May 30th. A trace of new snow on the crags.

After breakfast I checked the trotline. It pulled heavy, with a tugging now and then on the way in. Two burbot, a fifteen-incher and a nineteen-incher. A burbot is ugly, all mottled and bigheaded—it looks like the result of an eel getting mixed up with a codfish. It tastes a whole lot better than it looks. I skinned and cleaned the two before going to work and left the entrails on the beach for the sanitation department.

The cabin is growing. Twenty-eight logs are in place. Forty-four should do it, except for gable ends and the roof logs. It really looks a mess to see the butts extending way beyond the corners, but I will trim them off later on.

The burbot looks like an eel mixed up with a codfish. It’s ugly, but it has firm white flesh.

Rain halted operations for a spell.

When I started in again, I made a blunder. My mind must have been on the big ram I had been watching. I’d just finished a notch, had a real dandy fit, and was about ready to fasten it down when I noticed it was wrong end to! I tossed it to one side and started another. Guess a man needs an upset now and then to remind him that he doesn’t know as much as he thinks he does. Maybe that’s what the camp robber was trying to tell me.

May 31st. A weird-looking country this morning. The fog last night froze on the mountains, giving them a light gray appearance. That loon calling out of the vapor sounds like the spirit of Edgar Allan Poe.

The contrary log of yesterday carried over into today. I carefully fitted and fastened it down, and was selecting logs for the next course when I looked up and saw it was still wrong end to! How in the world did that happen? Two big ends together are proper but not three. I pried it off and flung it to the side. But why get shook up about it? It’s better to discover it now than when it’s buried beneath a course.

Thirty-five logs in place. Nine to go and I will be ready for the gables—those tricky triangular sections on each end beneath the pitch of the roof. The roof logs and the ridge will notch over them. Babe said he could fly in some plywood for a roof. There would be room to spare in the Stinson, but plywood seems too easy. I think I will stick with the pole idea instead. Run those spruce poles at right angles to the eave logs and the ridge, then decide the best way to cover them.

It was snowing a few flakes as I worked. Cool weather is the best kind to work in, although rain makes the logs slick. Very few insects about. No complaints there.

I have a kettle of navy beans soaking for tomorrow. Babe says they must be at least fifteen years old. At that rate they will need a long bath.

June 1st. Fog lifted early. This commuting to work by canoe is the best way yet.

Just fitted the jinx log into place when I heard a plane. It was Babe. I watched the T-craft glide in for a perfect landing on the calm lake. I’ve heard bush pilots say it is much easier to land where there is a ripple, because calm water distorts depth perception. I shoved off in the canoe and rounded the point to meet him at Spike’s beach.

Plenty of groceries this time. Fifty pounds of sugar, fifty pounds of flour, two gallons of honey, sixty pounds of spuds, two dozen eggs, half a slab of bacon, some rhubarb plants, plenty of mail, and some books … religious ones. I guess he has been working overtime on my philosophy from our last chat on the beach.

Babe had planted his potatoes yesterday. He was in a hurry. No time to visit. Wished he had time to inspect the building project. Next time he would. Right now he had a couple of prospectors to fly in somewhere. He would see me in a couple of weeks.

I got mail from all over. Brother Jake is flying up and down that California country. Wish I could talk him into coming up here and staying a spell. We’d see some sights in that little bird of his.

Sister Florence is going to make a set of curtains for my big window. Dad is fine but he wishes I had a large dog with me. I’ve thought about a dog. It would mess up my picture-taking for sure.

Sid Old is still soaking up the sun in New Mexico. The old boy has been off his feed lately. I could listen to him all day, spinning his yarns about the early horse-packing days on Kodiak: tying the diamond hitch, the cattle-killing bears.

Spike allows that he and Hope may drop in to Twin Lakes in August. Spike not quite up to snuff these days either. Sam Keith writes that the kids in the junior high school where he is vice principal are like beef critters smelling water after a long drive. They smell vacation. Wish I could get him up here with that willow wand of his when the grayling are having an orgy at the creek mouth. Good to hear from everybody. I guess part of a man’s root system has to be nourished by contacts with family and old friends.

The rhubarb plants should be put into the ground right away. Why not plant the whole garden patch while I’m at it?

I found the frost about four or five inches down. I drove the grub hoe into the soil as far as I could and stirred up the plot with a shallow spading. The loam seemed quite light and full of humus. I set out the rhubarb plants and watered them. Then I planted fifteen hills of potatoes, tucked in some onion sets, and sowed short rows of peas, carrots, beets, and rutabagas. Not much of a garden by Iowa standards, but it would tell me what I wanted to find out.

Finally back to the cabin building. I’m a better builder than I am a farmer anyway. Thirty-eight logs are in place and I’m almost ready for the eave logs.

Where are the camp robbers and the spruce squirrel? I miss seeing them. They are good companions, but work is really the best one of all.

A fine evening and I hated to waste it. The lake was flat calm and a joy to travel with quiet strokes of the paddle. My excuse was to prospect for some roof-pole timber near Whitefish Point. I found no great amount, and I returned to this side of the lake.

Using a sharp axe to even the picture window base.

The eave logs complete the side walls. With the kitchen window and picture window cut out, the structure is now ready for the gable ends to be framed.

June 3rd. I am ready for the eave logs and the gables. I marked out the windows and door and will cut far enough into each log so that once the eave logs are on, I can get the saw back through to finish the cutting.

The gables and the roof have occupied much of my thoughts lately. Up to this point my line level tells me the sides and ends are on the money. The course logs were selected carefully, and I have done the hewing necessary to keep the opposite sides level as the cabin grows. Five logs were very special. These were the twenty-footers, which along with the gable ends would be the backbone of the roof. Two would be eave logs, two purlin logs, and the last, the straightest, would be the ridge log. In pondering how to go about the gables, I pictured to myself the letter A. It would take four logs, one atop the other and each one shorter than the one beneath, to make a triangle up to the ridge log height I planned.

The eave logs are the top ones on the side walls. They would be different from the other wall logs in that they would overhang about a foot in the rear of the cabin and extend three feet beyond the front of the cabin, to hold the eaves and the porch roof. The purlin logs are roof beams running parallel with the length of the cabin, halfway between the eave logs and the ridge log. The roof poles would lie over them at right angles, from the ridge down across the eave logs.

Of course the ridge log still was not in place. To get it there, the fourth and shortest gable log would be spiked on top of the third one. The ridge would be seated on it, equally spaced between the purlins. There would be a framework of five logs, two (or eaves) at the top of the walls, one (the ridge) at the peak, and two (the purlins) in between, supporting the crossways roof poles.

The gable ends will be cut to the slope of the roof. The slope can be determined with a chalk line. I’ll drive a nail on top of the ridge pole, draw the string down along the face of the gable logs, just over the top of the purlins, to the eave nails. I’ll chalk the line, pull it tight, and snap it. The blue chalk lines slanting down the gable logs will represent the slope of the roof on each side. The gable logs then can be cut at the proper angle of the letter A I’ve pictured. The three-foot extension of the roof logs in front of the cabin will allow for three feet of shed-like entrance to the cabin.

That’s the way the project shapes up. Let’s see if we can do it.

June 4th. A good day to start the roof skeleton.

Another critic cruised past in the lake this morning, a real chip expert and wilderness engineer, Mr. Beaver. He probably got a little jealous of all the chips he saw, and to show what he thought of the whole deal, upended and spanked his tail on the surface before he disappeared.

Shortly afterward a pair of harlequin ducks came by for a look. The drake is handsome with those white splashes against gray and rusty patches of cinnamon.

My curiosity got the better of me and I had to glass the sheep in the high pasture. It was a sight to watch the moulting ewes grazing as the lambs frolicked about, jumping from a small rock and bounding over the greenery, bumping heads. It was a happy interruption to my work.

Peeled logs take time but are well worth the effort.

I find I can handle the twenty-footers easily enough by just lifting one end at a time. With the corners of the cabin not yet squared off, there are some long ends sticking out on which to rest logs as I muscle them up to eave level and beyond. I also have two logs leaning on end within the cabin, and by adjusting their tilt I can use them to position a log once it is up there. The ladder comes in handy, too.

The two eave logs were notched and fastened down according to plan. I cut the openings for the big window, the two smaller ones, and the opening for the door. I placed the first gable log on each end, and it was time to call it a day.

The roof skeleton should get the rest of its bones tomorrow.

June 5th. Good progress today. When you first think something through, you have a pretty good idea where you are going and eliminate a lot of mistakes.

I put up the gable ends, notched the purlin logs into them, and fastened down the ridge log. It went smoothly. It’s a good thing I put the eave log one row higher than I had originally planned, or I would have to dig out for headroom. Even now a six-footer won’t have any to spare, and I won’t have much more clearance myself.

The cabin is in a good spot. That up-the-lake wind is blocked by the timber and brush between the cabin and the mouth of Hope Creek.

As it now stands, the cabin looks as though logs are sticking out all over it like the quills of a riled porcupine. There’s much trimming to do in the morning. All logs are plenty long, so there will be no short ones to worry about.

June 6th. The time has come to cut the cabin down to size. First I filed the big saw. Then I trimmed the roof logs to the proper length. I trimmed the gable logs to the slope of the roof, and trimmed the wall logs on all four corners. What a difference! Log ends are all over the ground and the cabin is looking like a once-shaggy kid after a crew cut.

Now I have to start thinking about window and door frames, and the roof poles. I must find a stand of skinny timber for those. That means some prospecting in the standing lumberyards.

My cabin logs have magically changed form in the ten days since I cut the first notch. There are only four full-length logs left, and only one of those is halfway decent. Before it’s over, there will be a use for all of them.

June 7th. I do believe the growing season is at hand. The buckbrush and willows are leafing out fast now. The rhubarb is growing, and I notice my onion sets are spiking up through the earth.

Those window frames have been on my mind. I decided to do something about it. First I built a sawhorse workbench, then selected straight-grained sections of logs cut from the window and door openings. I chalked a line down each side, and with a thin-bladed wide chisel, I cut deep along the line on each side. Then I drove the hand axe into the end to split the board away from the log. That worked fine.

I smoothed the split sides with the drawknife to one and three-quarter inches wide. The result was a real nice board, so I continued to fashion others. Put in place and nailed, they look first-rate.

I finished the day cleaning the litter of wood chips. I mounded them in front of the door, beaver lodge style. Quite a pile for eleven days’ work—enough to impress that beaver.

I have given a lot of thought to chinking. I think I will try mixing moss and loose oakum to cut down on the amount of oakum. If oakum with its hemp fibers can caulk the seams in boats, it should be able to chink logs.

June 8th. I moved my mountain of wood chips and shavings. Then I gathered moss and spread it on the beach to dry. There is still ice under the six-inch-thick moss in the woods. I used oakum in the narrow seams, and a mixture of oakum and moss where the opening was more than one-quarter inch. Straight oakum is easier to use. I will have a tight cabin.

Much trimming to do. The framework improves with a “haircut” of the log ends.

June 9th. Today would be a day away from the job of building. I’ll look for pole timber up the lake.

I proceeded to the upper end of the lake, where I beached the canoe on the gravel bar and tied the painter to a willow clump. A “down-the-lake” wind might come up and work the canoe into the water, and it would be a long hike to retrieve it.

I walked along the flat, crossing and recrossing the creek that had its beginnings in the far-off snows. I found a dropped moose antler, a big one, and decided to pick it up on the way back. There were fox tracks and lynx tracks in the sand, and piles of old moose droppings.

The rockpile was finally before me, a huge jumble of gray-black, sharp-edged granite chunks all crusted with lichens. It was a natural lookout that commanded three canyons. I set up my spotting scope, wedging the legs of the tripod firmly amid the slim-fronded ferns that grew dagger-shaped in single clumps out of the rock crevices. Right off I spotted four caribou bulls grazing along the right fork of the creek bed. Then high on the slopes five good-looking Dall rams, one in a classic pose with all four feet together atop a crag, back humped against the sky.

Below them, four ewes moved in my direction. At mid-slope a bull moose on the edge of some cottonwoods was pulling at the willow brush, changing black and brown as he swung his antlers among the foliage. I saw an eagle wheeling in the air currents, pinions stiffened like outstretched fingers. Ground squirrels whistled. Life was all around.

On the way back to the beach I stooped to nibble on last season’s mossberries. They were a little tart to the tongue. I picked up the moose antler and wondered where the other might be. To my surprise I found the mate not 200 yards away. They made quite an awkward load to pack. It must be a relief to an old bull when the load falls off.

Just as I reached the canoe, it had to happen. An up-the-lake-wind! I battled against it for a spell, then decided to beach. Finding a warm spot in the sun I napped, waiting for the lake to flatten. It never really did, and I paddled back from point to point until I finally reached the cabin.

A good day. I forgot only one thing—something for lunch.

June 10th. Bright and clear. I hear the spruce squirrel, but he stays out of sight. He likes to shuck his spruce cones in private. The blueberry bushes are nearly leafed out and loaded with bloom.

I finished chinking the cabin. Then I put a log under the bottom log in front, to plug an opening there. I did the same in back and chinked them both. Now I am ready for the roof poles, which I will start cutting tomorrow.

The little sandpipers flying back and forth along the edge of the beach have a characteristic flight. A few quivering strokes of their wings, a brief sail, some more wing vibrations, and then wings rigid again as they glide to a landing and vanish. They blend in so well, they are invisible against the gravel until they move.

June 11th. I paddled up the lake to the foot of Crag Mountain. This was a pole-cutting day.

Good poles were not as plentiful as I figured, and I worked steadily to get forty-eight cut and packed to the beach by noon. The mosquitoes were out in force.

To peel the poles, I made a tripod of short sticks on which to rest one end of the pole while the other stuck into the bank, and put the drawknife to work. The bark flew.

June 12th. Today I finished peeling the poles, fifty in all, rafted them up, and moved them down the lake to my beach. A good pile, but I doubt there will be enough.

June 13th. Rain. Wrote a batch of letters—not a job to do on a good day. It cleared in the late afternoon, so I gathered sixteen more poles and peeled seven.

Readying the roof poles for installation.

June 14th. Not a cloud in the sky. A cool morning but no frost. My garden is all up except the potatoes, and they should be showing soon. The green onions are more than three inches tall.

I peeled the remainder of my roof poles and trimmed the knots close. Now to put them on, but how close? I decided on five inches center to center as they lay at right angles to the ridge log.

One side is nearly roofed and the other, about half. With only ten left, I must hunt more poles—about thirty if my calculations are right.

June 15th. I tried for a fish this morning at the mouth of Hope Creek. No luck. I did see the flash of a light-colored belly behind the lure. They are there.

I went pole prospecting below the creek mouth in the fine rain and cut fifteen—enough for one trip back up the lake. I tied the small ends side by side, ran the canoe into the butt-ends far enough to tie them to the bow thwart. It left me enough room to paddle from just forward of the stern, which worked real well—slow but effective transportation.

In the afternoon I finished the front end of the cabin roof and took count. I would need seventeen more poles. After scouting in the timber behind the cabin, I found seven.

A beautiful evening with a light breeze down the lake. A loon rode low in the water and trailed a wake of silver as it took flight.

June 16th. Where are my spuds? Maybe I planted them too deep.

Today I secured the roof poles over the gables and chinked them. A cabin roof takes time. A hundred poles to gather, transport, and peel, trim the knots, and notch them to fit over the purlin logs. I see where one more pole is needed. Soon I will be ready to saw the ends and fill the slots between the pole butts under the eaves. These fillers should be called squirrel frustrators. Give those characters an entrance and they can ruin a cabin.

June 17th. Up to greet the new day at 3:45 a.m. I am not sure of the time anymore. I have kept both my watch and clock wound but have not changed the setting. Now they are thirty minutes apart. Which one is right? No radio to check by. I don’t miss a radio a bit. I never thought one was in tune with the wilderness anyway. A man is on his own frequency out here.

On the job at five-thirty. I sawed the roof pole ends off to a proper eighteen-inch overhang. Now I am ready for the chore of plugging the gaps between the roof poles on top of the wall logs. If varmints are going to get into my cabin, they will have to work at it.

The camp robbers are back. Four were near the cabin today. They are marked somewhat like king-size chickadees. I like the way they come gliding softly in to settle on a spruce tip and tilt their heads from one side to the other as if they are critical of what I am doing. Some have a very dark plumage, almost black.