Читать книгу One Man's Wilderness, 50th Anniversary Edition - Sam Keith - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPreface

Although Dick Proenneke came originally from Primrose, Iowa, he will always be to me as truly Alaskan as willow brush and pointed spruce and jagged peaks against the sky. He embodies the spirit of the “Great Land.”

I met Dick in 1952 when I worked as a civilian on the Kodiak Naval Base. Together we explored the many wild bays of Kodiak and Afognak Islands where the giant brown bear left his tracks in the black sand, climbed mountains to the clear lakes hidden beyond their green shoulders, gorged ourselves on fat butter clams steamed over campfires that flickered before shelters of driftwood and saplings of spruce.

It was during these times that I observed and admired his wonderful gift of patience, his exceptional ability to improvise, his unbelievable stamina, and his consuming curiosity of all that was around him. Here was a remarkable blending of mechanical aptitude and genuine love of the natural scene, and even though I often saw him crawling over the complex machinery of the twentieth century, his coveralls smeared with grease, I always envisioned him in buckskins striding through the high mountain passes in the days of Lewis and Clark.

If a tough job had to be done, Dick was the man to do it. A tireless worker, his talents as a diesel mechanic were not only in demand on the base but eagerly sought by the contractors in town. His knowledge, his imagination, and his tenacity were more than stubborn machinery could resist.

His quiet efficiency fascinated me. I wondered about the days before he came to Alaska.

While performing his duties as a carpenter in the U.S. Navy during World War II, he was stricken with rheumatic fever. For six months he was bedridden. It kept him from shipping out into the fierce action that awaited in the Pacific, but more than anything else, it made him despise this weakness of his body that had temporarily disabled him. Once recovered, he set about proving to himself again and again that this repaired machine was going to outperform all others. He drove himself beyond common endurance. This former failing of his body became an obsession, and he mercilessly put it to the test at every opportunity.

After the war he went to diesel school. He could have remained there as an instructor, but yearnings from the other side of his nature had to be answered. He worked on a ranch as a sheep camp tender in the high lonesome places of Oregon. As the result of a friend’s urging and the prospect of starting a cattle ranch on Shuyak Island, he came to Alaska in 1950.

This dream soon vanished when the island proved unsuitable for the venture. A visit to a cattle spread on Kodiak further convinced the would-be partners that, for the time being at least, the Alaska ranch idea was out. They decided to go their separate ways.

For several years Dick worked as a heavy equipment operator and repairman on the naval base at Kodiak. He worked long, hard hours in all kinds of weather for construction contractors. He fished commercially for salmon. He worked for the Fish and Wildlife Service at King Salmon on the Alaska Peninsula. And though his living for the most part came from twisting bolts and welding steel, his heart was always in those faraway peaks that lost themselves in the clouds.

A turning point in Dick’s life came when a retired Navy captain who had a cabin in a remote wilderness area invited Dick to spend a few weeks with him and his wife. They had to fly in over the Alaska Range. This was Dick’s introduction to the Twin Lakes country, and he knew the day he left it that one day he would return.

The return came sooner than he expected. He was working for a contractor who was being pressured by union officials to hire only union men. Dick always felt he was his own man. His philosophy was simple: Do the job you must do and don’t worry about the hours or the conditions.

Here was the excuse Dick needed. He was fifty years old. Why not retire? He could afford the move.

“Get yourself off the hook,” he told the contractor. “That brush beyond the big hump has been calling for a long time and maybe I better answer while I’m able.”

That was in the spring of 1967.

He spent the following summer and fall in the Navy captain’s cabin at Twin Lakes. Scouting the area thoroughly, he finally selected his site and planned in detail the building of his cabin. In late July he cut his logs from a stand of white spruce, hauled them out of the timber, peeled them, piled them, and left them to weather through the harsh winter. Babe Alsworth, the bush pilot, flew him out just before freeze-up.

Dick returned to Iowa to see his folks and do his customary good deeds around the small town. There in the “flatlander” country he awaited the rush of spring. He had cabin logs on his mind. His ears were tuned for the clamoring of the geese that would send him north again.

Here is the account of a man living in an area as yet unspoiled by man’s advance, a land with all the purity that the land around us once held. Here is the account of a man living in a place where no roads lead in or out, where the nearest settlement is forty air miles over a rugged land spined with mountains, mattressed with muskeg, and gashed with river torrents.

Using Dick Proenneke’s rough journals as a guide, and knowing him as well as I did, I have tried to get into his mind and reveal the “flavor” of the man. This is my tribute to him, a celebration of his being in tune with his surroundings and what he did alone with simple tools and ingenuity in carving his masterpiece out of the beyond.

Sam Keith

Duxbury, Massachusetts (1973)

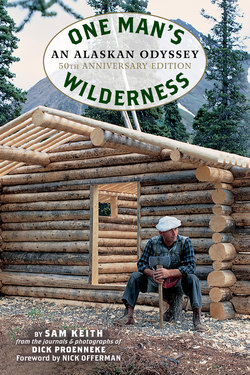

Looking up the lake from Low Pass