Читать книгу One Man's Wilderness, 50th Anniversary Edition - Sam Keith - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеForeword

BY NICK OFFERMAN

When you woke up today, did you turn on a light? Did any of your breakfast come out of a refrigerator? Was it prepared over a gas or electric range, or an open fire? Let’s say you had bacon, eggs and toast with butter, with a glass of orange juice. Did you raise or grow any of these food items yourself, or did they come to you through the vast network of food providers in America? Did you enjoy that breakfast in some sort of shelter, like an apartment or a house? Were you comfortably seated for eating, maybe utilizing a chair and a table or a counter? The answers to these questions likely bespeak the incredible amount of convenience that most of us have come to enjoy in developed nations, often as a matter of course. We tend to take these luxuries for granted without giving them a great deal of thought, because that’s what civilization does, among other things. It takes scientific advances that would have blown the minds of our ancestors only a hundred years ago and turns them into mass-produced products and services so commonplace that they are simply unremarkable.

One arguable advantage of this societal conditioning is that we are afforded more time for distractions. Because we can enjoy a glass of milk without needing to milk the cow, and we are generally not required to tend to our crops, livestock, or firewood, we can then turn our collective gaze toward more leisurely targets. This is time that we fill perhaps with reading books (ideally), or looking at social media on our phones or laptops, or watching entertainment in the form of online videos or television. Ironically, one of the most popular genres of reality entertainment across all of these mediums involves reading about or watching people perform the very tasks that modern technology is keeping us from needing to perform. Shows that require all sorts of cooking skills, shows about crafting timber frame buildings or simply improving one’s home with DIY techniques, shows about surviving in the wilderness, all seem to hold our fascination and provide a great deal of comfort. It’s a funny juxtaposition, but here we are.

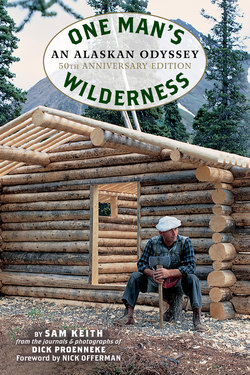

Which brings me to the subject at hand. To my way of thinking, this book (and the astonishingly good film that accompanies it, Alone In The Wilderness) is the original must-read DIY entertainment. There are elements in his writing that hearken back to Lewis and Clark or Laura Ingalls Wilder in their attention to the same unadulterated forests and streams, and the teeming wildlife inhabiting them. In the tradition of all great nature writing, this work understands the power of simple observation and reportage. In the early 1960s, Richard “Dick” Proenneke carved out for himself an astonishing way of living in the Alaskan wilderness, hundreds of miles from the nearest light bulb. I suppose there must be other people who have notched similar achievements over the years, but none of them kept so resplendent a journal while outing on such a damn fine display of competence, not to mention filming themselves on 8mm film stock with an incredible rate of success.

While you read this, it’s fun to imagine him not only building his cabin and cache, woodshed, privy, doors, windows and furniture, all while maintaining a constant vigilance of the natural seasons around him and their effect upon the animal and plant life, regardless of their inclusion in his diet (or not) but also regularly setting up a small movie camera on a tripod, lining up his shot and rolling the camera, only to then hustle into the frame and commence the action of the scene, whether that was hewing logs, ripping boards, or feeding the camp-robbing birds. He would then have had to safely preserve his film from the effects of light and temperature until it would presumably be sent away with his mail in the bi-monthly visits from Babe in his tiny seaplane. An astonishing accomplishment from soup to nuts.

Somehow Proenneke understood that his simple efforts—build shelter, stay warm, find/hunt food, observe nature, respect life—would be well worth documenting, and boy howdy was he right. If you like hearing a TV chef walk you through a recipe for enchiladas, just wait until you consume the creation of a log home in this volume, from the ground up. A notoriously talented diesel mechanic before relocating into the wild, the author displayed exceptional skill levels in woodworking, log/timber construction, engineering, chemistry, hunting, fishing, navigation, gardening, and journalism. He was dropped off next to an Alaskan lake with a bag of tools and a few minor conveniences, like matches and a sleeping bag, to see if he could survive for a year. As an experiment, that is pretty damn gutsy.

Not only is this a ripping good read, but it also serves up valuable inspiration in our own comfortable lives, what with our indoor plumbing and laundry machines. I think about Proenneke’s statement that his time in his cabin was the most interesting and rich experience of his life, and I understand the truth behind it: if you make the right choices, then a very simple life, devoid of distraction, has the best odds of being a happy life. Of course, that’s easy for him to say, sequestering himself away from civilization in a monastic existence. Some of us have to pursue simplicity and also deal with traffic, and answering emails, and so forth.

As I sit to my breakfast this morning, consisting of eggs that I did not gather from my own henhouse, I think about those eggs and from whence they were procured. They are the most grass-fed, free-range eggs I can find at my local healthy grocery store. Eggs-wise, I feel victorious, and now I will build my day from there. I decide to listen to an audio book on my way to my woodshop—the excellent The Shepherd’s Life by James Rebanks—continuing my indulgence in delicious, well-written nonfiction, describing the art of living in and profiting by the beautiful and harsh elements of Mother Nature; in his case, raising sheep in the hills of northern England. When I get to my shop, I will be using tools like chisels and planes to continue crafting a batch of nine soprano ukuleles. You best believe I will be sharpening those tools with care before I touch them to the wood. I don’t have much in the way of birdsong at the shop, so I’ll put on some Talking Heads today. There. That sounds like a day that might see me satisfied by the time I drive back across town.

Whatever it was that drove him to put his mettle to such an extreme test, it is we who benefit, by entertainment and by inspiration, thanks to these pages you hold in your hands. In a day and age when so few of us know how to do much with an axe and a tree, it is deeply comforting to read of the sure-handed actions of a man who did. And if you’re anything like me, it will goose you to get out your own chisel, as it were, and give it an extra honing before your next session making chips and shavings.

Nick Offerman

Los Angles, California (2018)