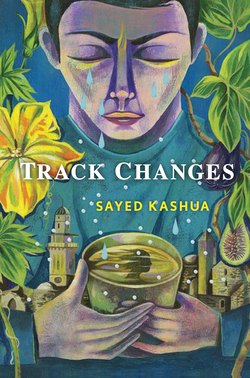

Читать книгу Track Changes - Sayed Kashua - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

7

ОглавлениеMy father’s condition, the doctors say, is critical but stable.

From Mom’s explanation I was able to grasp that after the catheterization Dad’s lungs filled with fluid and he wasn’t able to breathe. They hooked him up to a respirator and drained the liquid from his lungs. After a few hours, during which they thought they might lose him, the doctors were able to take him off the respirator and leave him hooked up only to the oxygen mask. Mom said it was important to keep an eye on the oximeter, and she showed me how to read the screen. “If it goes under eighty,” she said, “call the nurse immediately.” Another thing I had to keep an eye on was the nearly empty urine drainage bag, which dangled over the side of the bed. “When he starts expelling,” my mother said, claiming to have discussed this in detail with one of the cardiologists from Tira who works at Meir Hospital, “we’ll know that he’s getting better. An excellent cardiologist, that Ahmad, do you know him? He was in your grade. Maybe one grade behind you. He helped us a lot today. If he swings by, be on your best behavior and be grateful, although I doubt he’ll come because senior physicians don’t work night shifts.”

I watched the saturation levels on the oximeter, though I did not understand their significance. Sometimes they went up to ninety-two and sometimes they went down to eighty-five. The monitor, which presented my father’s condition in shimmering graphs and flickering numbers and lights, started to beep, and a nurse entered the room, silenced the beeping with the pressing of a button, and then turned down the volume of the machine to practically zero. Had she not silenced it, it would probably have continued beeping, because a red light flashed incessantly. I did not inquire of the nurse what the beeps and silences meant; I figured they knew their trade and I didn’t want to interfere.

I returned to the couch, which was positioned beneath the large window that spanned the length of the room and looked out on a high-rise construction site. It was now six in the evening in Illinois. My wife had responded to me earlier to say that everything was okay and that I should “pass on her warmest get-well wishes.” My youngest son was probably in the bath at this stage of the evening, and I figured I’d send him a message later, once he’d put on his superhero pajamas and was getting ready for bed. Usually I’m there with him till he falls asleep. Maybe I’ll even talk to him a little bit later, I thought. My daughter will be up later than the boys, but there’s not much chance she’ll want to talk to me. The weather app showed it to be ten degrees in Illinois and fifty in Kfar Saba. With a single tap I changed it from Fahrenheit to Celsius, which seemed more appropriate here. No snow predicted for tomorrow in Illinois and a light rain possible in Kfar Saba.

The nurse popped into the room once an hour, and each time she stepped in I stood up. She looked at my father, at the instruments and monitors, noted the urine volume in the bag, and jotted down some figures on the clipboard attached to the foot of the hospital bed.

“You can get yourself something to drink, if you want,” the nurse said, surprising me at close to five in the morning by addressing me directly. “There’s a little kitchenette there with coffee and tea, some bread, and cottage cheese and chocolate spread in the fridge.”

“Thanks so much,” I said apologetically, in light of the earlier incident, after I’d tried to give my father a drink straight from the bottle.

“Did you just get in?” she asked, tilting her head in the direction of the trolley suitcase in the corner of the ICU room.

“In the evening,” I said, and she nodded once and left the room.

It’s been two years since I’ve had black coffee from one of those red-and-black bags labeled “Turkish Coffee.” That was the coffee I used to have every morning in Jerusalem: two spoonsful, half a cup of hot water, a splash of milk, no sugar. I used to drink it in the newsroom, too, a cup almost hourly.

I didn’t find any Styrofoam cups in the kitchenette and didn’t want to bother the nurse, so I took two plastic cups from the water cooler and doubled them up so that they wouldn’t collapse from the heat. In the United States they don’t have this sort of cup, which is too thin, too see-through, too small, and so feeble they need to be held gingerly around the rim lest they fold in your hand. I walked slowly, cautious with the sloshing liquid, to the room where my father lay, in order to make sure that he had not woken up before I abandoned him for a cigarette.

On the ground floor, the square in front of the stores was empty. A young Arab man, not dressed in hospital scrubs, slowly pushed a large floor buffer, and over the hum of the machinery I could hear him singing along to a tune wafting out of his phone, which he had laid flat over the top of the machine. I didn’t recognize the song—it was new, apparently—and the hum of the machine prevented me from identifying the singer.

The notion that I hadn’t heard a single Arabic song since I left bothered me, as though I’d forgotten that I like Arabic music, if not the new stuff then at least the classics I used to hear in my parents’ house and that I loved in my childhood, detested in my adolescence, and am once again moved by in middle age. Surely there are a slew of singers that the young generation loves and that I haven’t even heard of, stars I don’t even know well enough to hate. And my kids? Do they even know a single Arab singer? Can they even recognize Umm Kulthum or Abdel Halim? When I get back I’ll be sure to play Arabic music for them. I’ll start with Fairuz—my father loved her voice so much—the children’s songs or maybe that song about Jerusalem. The kids must know that one, they must know it.

I evaded the floor cleaner and hoped he hadn’t seen me. You can’t step on the floor while it’s being cleaned. You have to wait until the water has fully dried and then wipe your shoes rigorously on the mat or the rag before stepping inside the house. Otherwise Mom is angry. The premorning air was cool, and I regretted not taking my jacket. Sometimes it seems to me that it is always cold at this time of day, irrespective of season and geography.

I sat down on a wooden bench along the divide between the old and new wings of the hospital and slowly brought the plastic cup to my mouth, tilting the coffee gently toward the brim so that the hot liquid just grazed my lips as I tested the temperature. Once I was sure the liquid would not scald my tongue, I blew into the cup, puckered my lips, and sucked up some of the hot coffee. The deeply familiar taste made me momentarily dizzy and I was not able to fully interpret the sensation: a swirl of memories, either pleasant or cruel. I shivered and placed the cup of coffee on the asphalt floor and threaded my right hand up beneath the sleeve of my sweater and felt the hairs bristling on my left arm. I lit a cigarette, took a long drag and held the smoke in my lungs until I released it with an equally long exhalation. The flashing lights of a muted ambulance siren cut through the morning air, the parking barricade rose to a vertical position, and the ambulance accelerated to the front of the old building. The ER was still in the same spot. There was no sense of unusual urgency in the actions of the paramedics, who set the gurney down and rolled it inside. I couldn’t see the face of the prone person, but I noticed that aside from the paramedics in uniform a young woman in a sweat suit stepped out of the ambulance, her back hunched and her arms locked across her chest. Behind me, once the stir of commotion was still, I heard whispering and turned my head. A young man stood at the foot of a dusky stairwell and looked as though he were hiding, popping his head out every now and again to make sure he was safe and whispering some unclear words in Arabic into his phone, a wide smile spread across his face. I managed to note that he was wearing a brown shirt similar to the one worn by the floor cleaner and decided they worked for the same employment agency. I imagined the young cleaner whispering on the phone to his beloved, who had woken up at dawn or perhaps had not gone to sleep at all, and she whispering back to him from bed so that no one would hear, or maybe she was actually silent. After all, what were the chances that she would have a room of her own and not one shared by sisters and other family members. I imagined her trying to keep silent, smiling, perhaps under the covers, listening to the young man in the brown shirt, her heart pounding with fright and hope. How jealous I was of the two contracted workers, who would undoubtedly finish their shifts and return home, to the homes in which they were born, never running the risk of disorientation while returning. I was jealous of the man who had no doubt about where he would build his home, where he would raise his children, in which soil he will be interred when he dies.

The envy quickly morphed into pain for what I had done to Palestine, a pain that I tried to dull with a big sip of coffee and a harsh drag off the cigarette. Oh, Tira, Tira, I will have to return. I must right that which I once wronged. I’ll get on my knees in the center of the village and will beg forgiveness from every passerby, from those who know the story and from those who’ve never heard my name.

“Just wanted to say good night,” I wrote to my wife in an SMS, without expecting a response.

Soon my mother will return to the hospital and relieve me, and I’ll go back to the house to sleep in the same childhood bed beneath the same window where I would put the pillow, so that I could look out until I could no longer keep my eyes open, ready for the worst, ears attuned to every sound, every movement.

I was always the last of my three brothers, my roommates, to close my eyes. I didn’t know how they could just let themselves fall asleep like that. Did they not hear the same stories that I heard from the neighbors? The one about the demon who appears at times as a girl or as a cat? How could they possibly fall asleep, particularly during those warm summer nights, when there was no choice but to leave the window open? People forget that there were no air conditioners back then, certainly not in Tira. Summer nights were hot, but the heat was bearable as long as the windows were open in a way that allowed a cross breeze. Americans don’t open the windows at all, not in the steamy summer and not in the freezing winter. Not in the autumn and not in the spring. And I, like them, have learned to seal myself in and keep the air-conditioning turned to its appropriate setting.

Soon I’ll be home, and the windows will surely be shut on account of winter. And the winter nights in Tira are especially cold in my recollection. First contact with the mattress was always painful and you had to inhale sharply and ball up beneath the covers until the bed was warmed. Soon I’ll be there and will once again be able to feel the caress of the mattress and the wool blanket. Then I’ll shut my eyes and again become the most devoted soldier I’ve ever been, a soldier who knows the best hiding places, the ones that no foreign invader could ever find.